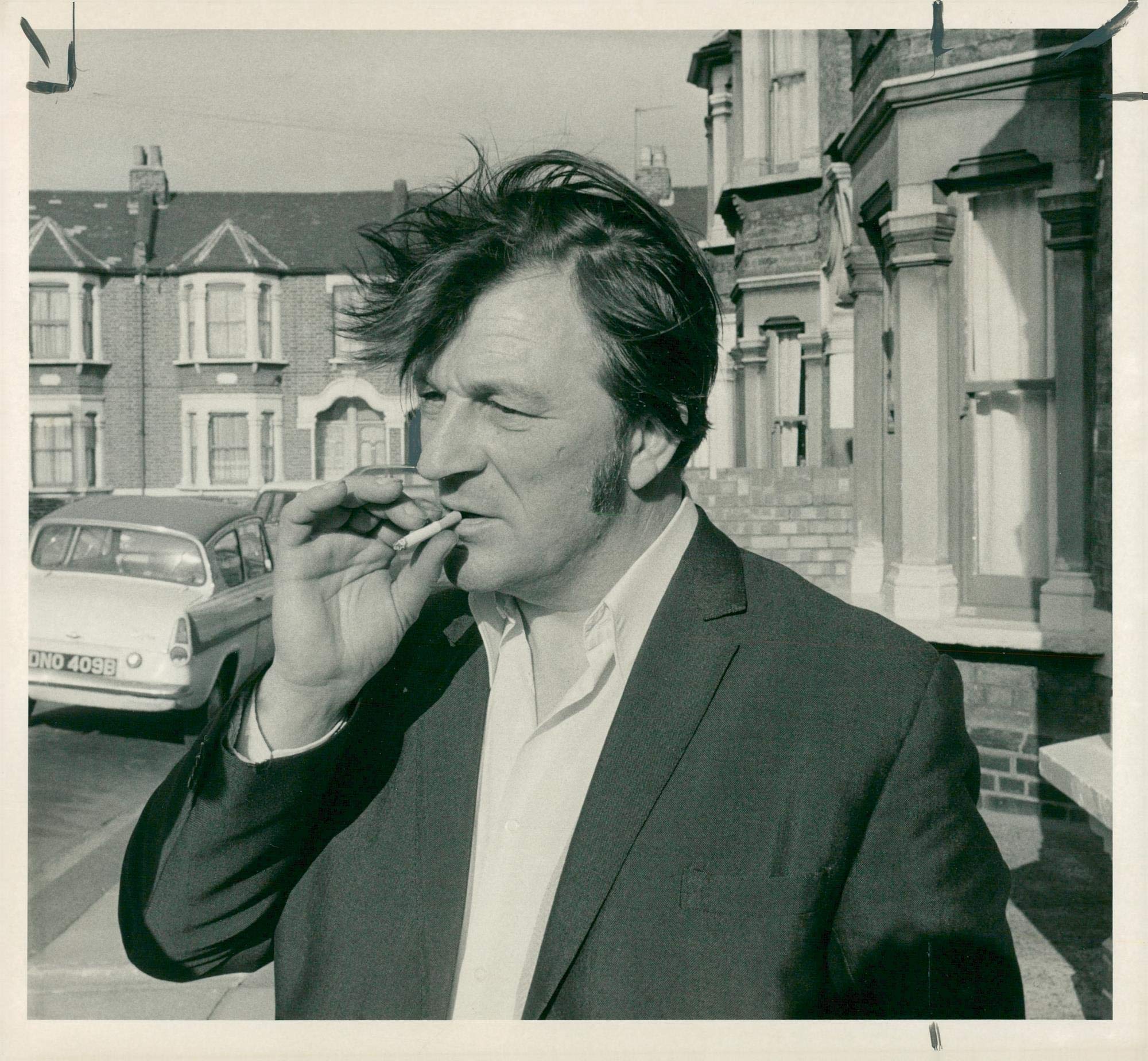

Who is Victor Turner?

Victor Turner (1920-1983) was a pioneering British cultural anthropologist whose innovative theories of symbols, ritual, and performance transformed the study of human society and culture. Over a prolific career spanning four decades, Turner developed a rich body of concepts and methods for interpreting the symbolic dimensions of social life, from the rites of passage of small-scale African societies to the pilgrimage traditions and countercultural movements of complex industrial nations. At the heart of his work was a fascination with the dynamic, processual qualities of culture – the ways in which symbols, rituals, and performances serve not merely to reflect or express social structures, but to actively shape and transform them. By illuminating the creative, generative power of symbolic action, Turner’s ideas have had a profound and enduring influence across the social sciences and humanities, from anthropology and religious studies to literature, theater, and political science.

Turner’s intellectual journey began with his early fieldwork among the Ndembu people of Zambia in the 1950s, where he developed his key concepts of the “ritual process,” “liminality,” and “communitas.” Drawing on Arnold van Gennep’s model of rites of passage, Turner showed how Ndembu rituals served to transition individuals and groups between stable social states by way of an intermediate, “liminal” phase of uncertainty, ambiguity, and potentiality. In the liminal state, participants were stripped of their normal social identities and distinctions, entering a fluid realm of communitas characterized by egalitarianism, spontaneity, and heightened fellow-feeling. For Turner, this dialectic of structure and anti-structure, order and openness, was the key to cultural creativity and transformation. I use Turners insights in therapy work frequently at my practice.

Over his career, Turner extended these foundational concepts to a wide range of social and cultural phenomena beyond the domain of ritual proper. He analyzed modern pilgrimage traditions, countercultural movements, and leisure activities as “liminoid” spaces of communitas and creative ferment within complex societies. He developed the idea of “social dramas” as processual units for understanding political contestation, legal disputes, and other arenas of social conflict and change. And he pioneered a more reflexive, performative approach to ethnography that recognized the co-creative role of the anthropologist in shaping the realities he or she describes.

At the same time, Turner’s work increasingly explored the bodily, sensory, and affective dimensions of symbolic action, bridging anthropology with fields like neuroscience and performance studies. He examined how rituals mobilize the autonomic nervous system to produce transformative states of consciousness, and he studied the symbolic and psychobiological bases of symbolic healing in indigenous and folk medical systems. In his later work, he developed a “performative” theory of culture that emphasized the active, embodied, and improvisational qualities of social life.

Throughout his oeuvre, Turner was guided by a humanistic vision of anthropology as a comparative science of meaning, value, and ethical aspiration. He saw the study of symbols, rituals, and performance as a way to understand the shared existential predicaments and creative potentialities of the human condition. At a time of rapid global change and cultural upheaval, Turner’s ideas continue to inspire new generations of scholars grappling with questions of identity, difference, and transformation in an interconnected world.

This essay provides an in-depth exploration of Turner’s key theories, ethnographic contributions, and interdisciplinary influence. It traces the development of his thought from his early fieldwork on Ndembu ritual symbolism to his later collaborations with theater director Richard Schechner and others in the emerging field of performance studies. Along the way, it examines Turner’s major works and conceptual innovations, from The Forest of Symbols and The Ritual Process to Process, Performance, and Pilgrimage and From Ritual to Theatre. By situating Turner’s oeuvre within its intellectual and historical context, the essay illuminates both the enduring significance of his ideas and their relevance for contemporary social and cultural analysis.

Symbols, Ritual Process, and Liminality

Turner’s first and most enduring contributions to anthropological theory emerged from his fieldwork among the Ndembu people of Zambia in the 1950s. In his early works, such as Schism and Continuity in an African Society (1957) and The Forest of Symbols (1967), Turner developed a novel approach to the study of ritual symbolism that emphasized the dynamic, processual qualities of symbolic action. Drawing on the semiotic theories of Ferdinand de Saussure and the phenomenology of Edmund Husserl and Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Turner argued that symbols are not merely passive reflections of social structure or expressions of collective sentiment, but active forces that shape perception, emotion, and behavior in complex and often paradoxical ways.

For Turner, the key to understanding the power of symbols lay in their multivocality – their ability to condense and unify disparate meanings and associations. In Ndembu rituals, for example, the mudyi tree served as a dominant symbol that brought together ideas of womanhood, matriliny, the continuity of the social group, the power of chiefs and ancestors, and the mystery of the sacred. By combining multiple meanings in a single symbolic form, Turner argued, symbols create a kind of semantic excess or surplus that can be drawn upon in different ways by different actors and interests. This polysemy of symbols makes them potent tools for social and cultural transformation.

Turner’s most influential concept for understanding the transformative power of symbols was the notion of the “ritual process.” Building on Arnold van Gennep’s model of rites of passage, Turner argued that many rituals serve to transition individuals or groups between stable social states or statuses by way of an intermediate, “liminal” phase characterized by ambiguity, uncertainty, and potentiality. In the liminal state, participants are stripped of their normal social roles and distinctions, entering a fluid, egalitarian realm that Turner called “communitas.”

For Turner, liminality and communitas were the key to cultural creativity and change. By suspending the norms and structures of everyday life, the liminal phase creates a space of openness and possibility in which new forms of social relationship and identity can emerge. In communitas, individuals experience a heightened sense of solidarity, spontaneity, and fellow-feeling that can serve as a template for new modes of being and belonging. At the same time, the liminal state is inherently unstable and must eventually give way to a new social order – one that may incorporate elements of the creative ferment of communitas, but which ultimately reinstates structure and hierarchy.

Turner developed these ideas through a close comparative study of Ndembu rituals, showing how symbols like the mudyi tree operated differently in different ritual contexts to effect transitions between social states. In the female puberty ritual of Nkang’a, for example, the mudyi tree symbolized the initiate’s transition from childhood to adulthood and her incorporation into the matrilineal group. In the male circumcision ritual of Mukanda, by contrast, the mudyi tree represented the separation of the initiates from the domestic world of women and their transformation into adult men and warriors.

Throughout his analysis, Turner emphasized the dialectical relationship between structure and anti-structure, order and openness, in the ritual process. He showed how rituals serve not merely to reflect or legitimate existing social arrangements, but to actively transform them by way of liminal inversions and transgressions. In this sense, Turner’s work anticipated later developments in social theory, such as Pierre Bourdieu’s notions of practice and habitus, that sought to move beyond static, functionalist models of society to more dynamic, generative understandings of culture.

At the same time, Turner’s concepts of liminality and communitas had a profound influence beyond the domain of ritual studies proper. In works like The Ritual Process (1969) and Dramas, Fields, and Metaphors (1974), Turner extended these ideas to a wide range of social and cultural phenomena, from pilgrimage and carnival to revolution and countercultural movements. He argued that the desire for communitas and the creative ferment of the liminal state are universal human potentialities that find expression in different ways in different societies and historical moments.

In complex industrial societies, Turner suggested, the experiences of liminality and communitas are often displaced onto “liminoid” phenomena outside the ritual domain proper, such as art, leisure, and popular entertainment. In these contexts, the creative and subversive potential of the liminal is often commodified and contained, but it can still serve as a space of experimentation and critique. Turner’s ideas have been widely taken up by scholars studying contemporary social movements, subcultures, and forms of popular resistance, who have found in his work a powerful framework for understanding the symbolic and performative dimensions of political struggle.

Pilgrimage and Communitas

One of the most influential extensions of Turner’s ritual theory was his analysis of pilgrimage as a form of liminoid phenomena in complex societies. In works like Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture (1978), co-authored with his wife Edith Turner, and Process, Performance, and Pilgrimage (1979), Turner argued that pilgrimage shares many structural features with rites of passage, serving to transition individuals and groups between social states by way of an extended liminal phase.

Like initiates in a rite of passage, pilgrims leave behind their normal social roles and statuses to enter a state of literal and symbolic marginality. They often undergo physical ordeals and tests of faith that serve to strip away their old identities and open them up to new spiritual and social possibilities. At the pilgrimage site itself, they enter a liminal realm of communitas, characterized by egalitarianism, spontaneity, and intense experiences of solidarity and fellow-feeling with other pilgrims.

For Turner, the power of pilgrimage lies in its ability to generate a sense of communitas that transcends the everyday structures and divisions of social life. At the same time, pilgrimage is never entirely outside or opposed to structure, but serves to renew and revitalize the social order by providing a space for the creative reimagining of social relations. In this sense, pilgrimage is both a reflection of and a challenge to the larger society in which it takes place.

Turner’s analysis of pilgrimage drew on his comparative study of Christian and other pilgrimage traditions around the world. He was particularly interested in the ways in which pilgrimage could serve as a vehicle for social and political critique, as in the case of the medieval European “People’s Crusades” or the Latin American folk-Catholic tradition of “liberation theology.” At the same time, he recognized the ambivalent and contested nature of pilgrimage, as different groups and interests seek to control and define the meaning of the sacred journey.

In his later work, Turner expanded his conception of pilgrimage to include secular forms of travel and tourism, arguing that these too could serve as spaces of liminality and communitas in modern societies. He coined the term “liminoid” to describe these quasi-ritual phenomena, which he saw as increasingly central to the cultural and social life of complex industrial nations. Today, Turner’s ideas continue to inspire new research on the transformative potential of travel, from backpacking and eco-tourism to diaspora and migration.

Social Drama and Performative Ethnography

Another key area of Turner’s theoretical innovation was his concept of the “social drama.” Drawing on his early work on Ndembu rituals of conflict resolution, Turner developed a model of social dramas as processual units of social life that unfold in four main phases: breach, crisis, redress, and reintegration or recognition of schism.

For Turner, social dramas are not confined to traditional societies or the domain of ritual proper, but are a ubiquitous feature of human social life. They can erupt in any arena of social interaction where there is a public breach or violation of a norm or rule of conduct. This breach triggers a phase of mounting crisis, as different actors take sides and the conflict escalates. The crisis is followed by a phase of redress, in which various formal and informal mechanisms are brought to bear to resolve the conflict, from legal procedures and political negotiations to religious rituals and artistic performances. Finally, the social drama concludes either with the reintegration of the offending parties into the social order, or with the recognition of an irreparable schism or breach.

Turner saw social dramas as key sites for the study of social and cultural change. By tracing the unfolding of social dramas in different ethnographic contexts, he argued, anthropologists could gain insight into the dynamic processes by which social norms and values are contested, negotiated, and transformed over time. At the same time, social dramas serve as a kind of meta-commentary on the society in which they take place, revealing the deep structures and contradictions that underlie the social order.

Turner’s model of social drama had a profound influence on the development of political anthropology and the study of conflict and legal processes. It has been widely applied to the analysis of political crises, social movements, and public controversies, from the Watergate scandal to the Arab Spring uprisings. At the same time, Turner’s work helped to pioneer a more reflexive and performative approach to ethnography, one that recognized the co-creative role of the anthropologist in shaping the realities he or she describes.

In his later work, Turner increasingly explored the implications of his social drama theory for the practice of ethnography itself. He came to see ethnography as a kind of performative practice, in which the anthropologist and his or her informants collaborate in the creation of cultural meanings and understandings. This perspective challenged traditional notions of ethnographic authority and objectivity, emphasizing instead the dialogical and improvisational nature of fieldwork.

Turner’s performative approach to ethnography was shaped by his collaborations with theater director Richard Schechner and others in the emerging field of performance studies. In works like From Ritual to Theatre (1982) and The Anthropology of Performance (1986), Turner and Schechner explored the continuities between ritual, theater, and other forms of cultural performance. They argued that performances are not merely reflections of pre-existing social realities, but are themselves constitutive of social life, shaping identities, relationships, and meanings in powerful ways.

For Turner, the study of performance offered a way to bridge the gap between anthropology and the arts, and to develop a more experiential and embodied approach to cultural analysis. He saw performance as a key site for the creation and transformation of cultural meanings, and he believed that anthropologists had much to learn from the techniques and insights of theater and other performing arts.

Today, Turner’s performative approach to ethnography and his insights into the social and cultural significance of performance have had a wide-ranging impact across the social sciences and humanities. His ideas have been taken up by scholars in fields as diverse as theater studies, performance art, cultural studies, and political science, who have found in his work a powerful framework for understanding the symbolic and expressive dimensions of human social life.

Play, Flow, and Ritual Improvisation

Another key theme in Turner’s work was the study of play and ritual improvisation as creative and regenerative social processes. Drawing on the work of Johan Huizinga, Roger Caillois, and others, Turner argued that play is a fundamental human capacity that is closely linked to the experiences of liminality and communitas in ritual and other social contexts.

For Turner, play is not merely a frivolous or unproductive activity, but a vital mode of social interaction that serves important cognitive, emotional, and cultural functions. Through play, individuals and groups can experiment with new roles and identities, test social boundaries and norms, and explore alternative ways of being and relating to others. In this sense, play is a kind of liminal space or “play frame” that suspends the ordinary rules and structures of social life, allowing for creativity, improvisation, and transformation.

Turner was particularly interested in the ways in which play and improvisation operate within the context of ritual and other forms of cultural performance. He argued that even the most highly structured and formalized rituals always involve an element of spontaneity and creativity, as participants adapt and innovate in response to changing circumstances and contingencies. This improvisational quality is what gives rituals their transformative power, allowing them to generate new social and cultural meanings in the moment of performance.

In his later work, Turner drew on the concept of “flow” developed by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi to describe the heightened states of consciousness and creative absorption that can arise in the context of play and ritual. Flow states are characterized by a sense of effortless control, deep concentration, and loss of self-consciousness, and they are often associated with feelings of joy, mastery, and transcendence. For Turner, flow states are a key component of the ritual process, allowing participants to access deeper levels of meaning and experience that are not available in ordinary waking consciousness.

Turner’s insights into the social and cultural significance of play and improvisation have had a wide-ranging impact across the social sciences and humanities. His ideas have been taken up by scholars in fields such as performance studies, game studies, and the anthropology of art, who have explored the ways in which play and creativity operate in different cultural and historical contexts. At the same time, Turner’s work has helped to inspire new forms of experimental and improvisational performance, from the “happenings” of the 1960s to contemporary site-specific and participatory theater.

Body, Brain, and Culture

In his later work, Turner became increasingly interested in the bodily and neurobiological dimensions of symbolic action and experience. Drawing on the insights of phenomenology, somatics, and the emerging field of neuroanthropology, he explored the ways in which cultural meanings and practices are deeply rooted in the structures and processes of the human body and brain.

For Turner, the body is not merely a passive object or instrument of cultural expression, but an active and creative agent in its own right. He argued that many rituals and other forms of symbolic action work by directly manipulating the body and its autonomic responses, inducing altered states of consciousness and heightened emotional arousal that can have powerful transformative effects. In this sense, the body is not just a vehicle for cultural meanings, but a generative source of meaning in itself.

Turner was particularly interested in the role of the autonomic nervous system in mediating the effects of ritual and other forms of symbolic action. He argued that many rituals work by inducing a state of “somatic-symbolic resonance,” in which the rhythms and patterns of bodily movement, breath, and vocalization become synchronized with the symbolic meanings and narratives of the ritual. This resonance between body and symbol can generate powerful experiences of transcendence, catharsis, and spiritual transformation.

Turner’s interest in the bodily and neurobiological dimensions of ritual led him to engage with the emerging field of medical anthropology and the study of symbolic healing practices in different cultures. In works like The Drums of Affliction (1968) and “Symbols in Ndembu Ritual” (1958), Turner explored the ways in which indigenous healing rituals work by mobilizing the body’s innate healing capacities through the manipulation of symbols and sensory stimuli. He argued that these rituals often have a powerful placebo effect, inducing psychosomatic changes that can lead to genuine physiological healing.

At the same time, Turner recognized that the relationship between body, brain, and culture is not a one-way street, but a complex and dynamic interaction. He argued that cultural meanings and practices can shape the development and functioning of the brain and nervous system in profound ways, and that different cultural environments can give rise to different patterns of embodied experience and consciousness.

Turner’s insights into the bodily and neurobiological dimensions of culture have had a significant impact on the development of medical anthropology, psychological anthropology, and the study of embodiment and consciousness. His work has helped to bridge the gap between the biological and cultural sciences, offering a more integrated and holistic understanding of the human condition. Today, Turner’s ideas continue to inspire new research on the complex interplay between body, brain, and culture in shaping human experience and social life.

Comparative Symbology and Literary Analysis

Throughout his career, Turner was deeply interested in the comparative study of symbols and their role in shaping social and cultural processes. He argued that symbols are not merely passive reflections of pre-existing social realities, but active agents that can generate new meanings and transform social relations in powerful ways.

In his early work on Ndembu ritual, Turner developed a sophisticated framework for analyzing the structure and function of symbols in different cultural contexts. He argued that symbols can operate at multiple levels of meaning, from the exegetical and interpretive to the operational and positional. Exegetical meaning refers to the overt, conscious interpretations that people give to symbols, while operational meaning refers to the ways in which symbols function within the context of ritual and social action. Positional meaning, meanwhile, refers to the ways in which symbols are related to other symbols within a larger symbolic system or cosmology.

Turner’s approach to symbolic analysis emphasized the multivocality and polysemy of symbols, their ability to condense and unify multiple meanings and associations. He argued that dominant symbols, like the mudyi tree in Ndembu ritual, often serve as a kind of semantic nexus or hub, linking together disparate domains of social life and experience. At the same time, he recognized that the meanings of symbols are never fixed or univocal, but are always open to contestation and reinterpretation by different social actors and groups.

In his later work, Turner expanded his comparative study of symbols to include literary and artistic works from different cultural traditions. He was particularly interested in the ways in which literature and art could serve as a kind of cultural performance, enacting and transforming social meanings and values in powerful ways. In works like “Myth and Symbol” (1974) and “Social Dramas and Stories about Them” (1980), Turner explored the ways in which literary and artistic symbols operate within larger social and cultural contexts, shaping and reflecting broader patterns of meaning and experience.

Turner’s comparative approach to symbolic analysis has had a significant impact on the development of literary theory and criticism, as well as the study of mythology and folklore. His ideas have been taken up by scholars in fields such as comparative literature, cultural studies, and the anthropology of art, who have explored the ways in which symbols and narratives operate across different cultural and historical contexts. At the same time, Turner’s work has helped to inspire new forms of creative and experimental writing, from the “ethnopoetics” of Jerome Rothenberg and Dennis Tedlock to the “border-crossing” fictions of Gloria Anzaldúa and others.

Processual Symbolic Analysis

One of Turner’s most important contributions to the study of symbols was his development of a processual approach to symbolic analysis. Rather than viewing symbols as static or fixed entities, Turner argued that they are always in a state of flux and transformation, shaped by the ongoing processes of social and cultural life.

Central to Turner’s processual approach was his distinction between the “exegetical,” “operational,” and “positional” meanings of symbols. Exegetical meaning refers to the overt, conscious interpretations that people give to symbols, often in the form of myths, stories, or doctrines. Operational meaning, meanwhile, refers to the ways in which symbols function within the context of ritual and social action, shaping patterns of behavior and interaction. Positional meaning refers to the ways in which symbols are related to other symbols within a larger symbolic system or cosmology, forming complex networks of association and contrast.

For Turner, the meanings of symbols are never fixed or univocal, but are always multivocal and polysemous, open to multiple interpretations and uses by different social actors and groups. He argued that symbols often condense and unify disparate meanings and experiences, serving as a kind of semantic bridge between different domains of social life. At the same time, he recognized that the meanings of symbols are always contextual and situational, shaped by the specific social and cultural contexts in which they are used and interpreted.

Turner was particularly interested in the ways in which symbols operate within the context of ritual and other forms of cultural performance. He argued that rituals often involve the manipulation of “dominant symbols,” which serve as a kind of semantic hub or nexus, linking together multiple domains of meaning and experience. These dominant symbols are often surrounded by clusters of “instrumental symbols,” which serve to elaborate and specify their meanings in different contexts.

For example, in his analysis of Ndembu ritual, Turner showed how the mudyi tree serves as a dominant symbol, condensing multiple meanings related to womanhood, fertility, and social continuity. This dominant symbol is elaborated by a range of instrumental symbols, such as the milk tree (representing femininity and nurturance) and the mukula tree (representing masculinity and strength). By tracing the processual unfolding of these symbolic complexes within the context of ritual, Turner was able to shed light on the dynamic interplay of structure and anti-structure, order and communitas, in shaping Ndembu social life.

Turner’s processual approach to symbolic analysis has had a significant impact on the development of anthropological theory and method. His ideas have been taken up by scholars in fields such as cultural psychology, cognitive anthropology, and the study of religion, who have explored the ways in which symbols shape and reflect patterns of thought, feeling, and action in different cultural contexts. At the same time, Turner’s work has helped to inspire new forms of ethnographic writing and representation, from the “thick description” of Clifford Geertz to the experimental “poetics” of James Clifford and George Marcus.

Ritual and Transgression

Another key theme in Turner’s work was the relationship between ritual and transgression, or the ways in which rituals can serve to challenge and transform social norms and boundaries. Drawing on the work of Georges Bataille, Mary Douglas, and others, Turner argued that many rituals involve a kind of sacred transgression or violation of taboos, which can serve to release powerful emotional and psychological energies and generate new forms of social and cultural meaning.

For Turner, the transgressive power of ritual is closely linked to the experiences of liminality and communitas that he explored in his earlier work. He argued that the liminal phase of rituals often involves a kind of symbolic or literal inversion of normal social roles and hierarchies, as participants are stripped of their usual statuses and identities. In this context, ritual transgressions can serve to challenge and subvert the dominant social order, creating a space of creative possibility and transformation.

Turner was particularly interested in the ways in which rituals can serve to channel and contain social conflicts and tensions through symbolic forms of transgression. He argued that many rituals involve a kind of “ritual joking” or “ritual obscenity,” in which participants engage in playful or subversive behavior that would be forbidden in ordinary social contexts. These ritual transgressions can serve to defuse social tensions and conflicts, providing a safe space for the expression of repressed emotions and desires.

At the same time, Turner recognized that ritual transgressions are always double-edged, holding the potential for both creative transformation and destructive chaos. He argued that rituals often involve a delicate balance between the forces of order and disorder, structure and anti-structure. While the liminal phase of rituals can create a space of creative possibility, it is always followed by a phase of re-integration, in which the social order is reaffirmed and restored.

Turner’s insights into the transgressive power of ritual have had a significant impact on the study of religion, politics, and social change. His ideas have been taken up by scholars in fields such as cultural studies, political anthropology, and the study of social movements, who have explored the ways in which rituals and other forms of cultural performance can serve to challenge and transform dominant social norms and structures.

Political Anthropology and Power

Turner’s work on ritual and transgression also had important implications for the study of political power and resistance. Drawing on his analysis of Ndembu rituals of conflict resolution, Turner developed a model of political processes as a kind of “social drama,” involving a dialectic of structure and anti-structure, order and disorder.

For Turner, political conflicts and struggles often unfold in a series of dramatic phases, beginning with a breach or violation of social norms, followed by a phase of mounting crisis and redressive action, and culminating in either the reintegration of the social order or the recognition of an irreparable schism. He argued that these social dramas are not confined to traditional societies, but are a ubiquitous feature of political life in all human societies.

Turner was particularly interested in the ways in which marginalized or subordinated groups can use rituals and other forms of cultural performance to challenge and resist dominant power structures. He argued that the liminal phase of rituals can create a space of political contestation and critique, in which the taken-for-granted assumptions and values of the dominant social order can be called into question.

At the same time, Turner recognized that the relationship between ritual and politics is always complex and ambivalent. While rituals can serve to challenge and transform political power structures, they can also be used to legitimate and reinforce them. He argued that political elites often seek to co-opt and control the symbolic resources of ritual in order to bolster their own authority and legitimacy.

Turner’s insights into the political dimensions of ritual have had a significant impact on the development of political anthropology and the study of power and resistance. His ideas have been taken up by scholars in fields such as postcolonial studies, critical theory, and the study of globalization, who have explored the ways in which rituals and other forms of cultural performance can serve as sites of political contestation and struggle in different historical and cultural contexts.

Schism and Continuity in an African Society

One of Turner’s most important ethnographic works was his 1957 book Schism and Continuity in an African Society, based on his fieldwork among the Ndembu people of Zambia. In this work, Turner explored the ways in which Ndembu society was shaped by ongoing processes of conflict and change, as different groups and factions struggled for power and influence.

Central to Turner’s analysis was his concept of the “social drama,” which he developed through a close study of Ndembu rituals of conflict resolution. He argued that Ndembu society was characterized by a high degree of structural tension and instability, as different lineages and interest groups competed for resources and political power. These tensions often erupted into open conflicts, which were then resolved through a series of ritual performances and symbolic negotiations.

Turner showed how Ndembu rituals of affliction, such as the famous Ihamba and Chihamba rituals, served to channel and contain these social conflicts, providing a symbolic framework for the expression and resolution of underlying tensions. He argued that these rituals worked by transforming the social and political relationships between the parties involved, creating a new sense of solidarity and communitas in the face of division and strife.

At the same time, Turner recognized that Ndembu rituals were not always successful in resolving social conflicts, and that they could sometimes lead to the emergence of new schisms and divisions within the community. He showed how the increasing influence of colonialism, Christianity, and other external forces was transforming Ndembu society in complex and unpredictable ways, leading to the emergence of new forms of ritual and political action.

Turner’s analysis of Ndembu society had a significant impact on the development of African anthropology and the study of social change and conflict. His insights into the dynamic interplay of structure and process, order and disorder, in shaping African social life have continued to inspire new generations of scholars and researchers. At the same time, his work has helped to challenge Western stereotypes of African societies as static, timeless, and unchanging, highlighting the complex and dynamic nature of African cultures and histories.

Performance, Postmodernism, and Experimental Ethnography

In the later years of his career, Turner became increasingly interested in the relationship between anthropology and the performing arts, and in the ways in which ethnography could be transformed through a more experimental and performative approach. Working in collaboration with theater director Richard Schechner and others, Turner helped to pioneer the field of performance studies, which explored the cultural and political dimensions of ritual, theater, and other forms of performative action.

Central to Turner’s performative approach was his concept of the “social drama,” which he saw as a kind of cultural performance that could be studied and analyzed like a theatrical event. He argued that social dramas were not simply reflections of pre-existing social structures, but were themselves constitutive of social reality, shaping and transforming the very relationships and identities they enacted.

Turner’s performative approach to ethnography was also shaped by his engagement with postmodern theory and the “crisis of representation” in anthropology. He argued that traditional ethnographic methods, based on the ideal of the detached, objective observer, were inadequate for capturing the complex and fluid nature of cultural performances. Instead, he advocated for a more reflexive and experimental approach, one that recognized the co-creative role of the ethnographer in shaping the realities he or she described.

In his later works, such as The Anthropology of Performance (1987) and The Anthropology of Experience (1986), Turner explored the ways in which ethnography could be transformed through a more embodied, sensory, and collaborative approach. He argued that ethnographers should seek to engage with their subjects not simply as informants or objects of study, but as co-performers and co-creators of cultural meaning. This approach required a new kind of ethnographic writing, one that blurred the boundaries between description, interpretation, and performance.

Turner’s performative approach to ethnography has had a significant impact on the development of anthropology and the social sciences more broadly. His ideas have been taken up by scholars in fields such as performance studies, cultural studies, and experimental ethnography, who have explored new ways of representing and engaging with cultural phenomena. At the same time, his work has helped to inspire new forms of artistic and activist practice, from community-based theater to participatory action research.

Legacy and Relevance

Victor Turner’s work has left an indelible mark on the field of anthropology and beyond. His insights into the social and cultural dimensions of symbols, ritual, and performance have shaped the way we understand the human experience, from the most intimate aspects of personal identity to the broadest patterns of social and political life.

Perhaps most importantly, Turner’s work has helped to bridge the gap between the humanities and the social sciences, showing how the study of culture and society can be enriched by insights from fields such as literature, art, and performance. His concepts of liminality, communitas, and social drama have become key tools for understanding the ways in which individuals and groups navigate the complex and often contradictory demands of social life, from the most traditional societies to the most modern and globalized.

At the same time, Turner’s work has helped to challenge and transform the very nature of anthropological inquiry. His performative approach to ethnography has opened up new ways of engaging with cultural phenomena, moving beyond the detached, objective stance of traditional fieldwork to a more collaborative, reflexive, and experimental mode of inquiry. His insights into the embodied, sensory, and affective dimensions of human experience have helped to push the boundaries of what counts as valid anthropological knowledge.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Anthropology

0 Comments