Key Points:

- Different psychotherapy modalities target distinct brain networks and memory systems, leading to varying treatment outcomes for different types of trauma.

- The triune brain model (MacLean) and research on emotional memory (LeDoux) and lateralization of brain function (Gazzaniga) provide a neuroscientific framework for understanding the impact of trauma on the brain.

- Personality factors and individual differences in brain organization, as revealed by qEEG brain mapping, influence the subjective experience of trauma and the response to different therapies.

- Experiential and somatic therapies, such as Brainspotting, EMDR, Jungian analysis, Internal Family Systems, and Somatic Experiencing, engage subcortical networks and implicit memory systems that are often overlooked in cognitive therapies.

- Effective trauma treatment requires an integrative approach that honors the unique phenomenology of each individual’s experience and targets the relevant brain networks and memory systems.

Trauma is a complex phenomenon that leaves an indelible mark on the brain, mind, and body. Recent advances in neuroscience have revolutionized our understanding of how traumatic experiences are encoded, stored, and processed in the brain. By integrating these insights with the wisdom of various psychotherapy modalities, we can develop a more comprehensive and effective approach to trauma treatment.

At the heart of this integrative perspective is the recognition that different brain networks and memory systems are involved in the processing of traumatic experiences. The triune brain model, proposed by neuroscientist Paul MacLean, provides a useful framework for understanding these systems. According to MacLean, the brain can be divided into three main regions: the reptilian brain (brainstem), the paleomammalian brain (limbic system), and the neomammalian brain (neocortex). Each of these regions plays a distinct role in emotional processing and memory formation.

The work of Joseph LeDoux on emotional memory further illuminates the neural underpinnings of trauma. LeDoux has shown that the amygdala, a key structure in the limbic system, can encode and store emotional memories independently of the hippocampus and cortical regions involved in conscious, declarative memory. This suggests that traumatic experiences can be “remembered” in the body and the subcortical brain, even when they are not accessible to conscious recall.

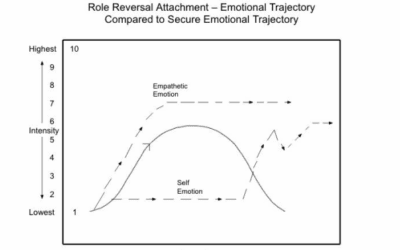

The lateralization of brain function, as demonstrated by Michael Gazzaniga’s split-brain research, adds another layer of complexity to the processing of trauma. The right hemisphere, which is dominant for nonverbal, emotional, and body-based processing, may be particularly important in the encoding and storage of traumatic memories. This has implications for the types of therapies that may be most effective in targeting these subcortical, right-brain networks.

Quantitative EEG (qEEG) brain mapping studies have revealed significant individual differences in brain organization and function, which can influence the subjective experience of trauma and the response to different treatment approaches. These differences may be related to personality factors, attachment styles, and other developmental experiences that shape the brain’s wiring and connectivity.

Given this complex neuroscientific landscape, it is not surprising that different psychotherapy modalities target different aspects of the trauma response. Cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT), for instance, focus primarily on explicit, declarative memory systems and the neocortical regions involved in conscious thought and emotional regulation. While these approaches can be helpful for some individuals, they may be less effective in targeting the subcortical, implicit memory systems that are often at the core of traumatic stress.

Experiential and somatic therapies, such as Brainspotting, EMDR, Jungian analysis, Internal Family Systems (IFS), and Somatic Experiencing, place greater emphasis on accessing and processing these subcortical networks. By working with body sensations, imagery, and implicit memory fragments, these approaches aim to facilitate the integration of traumatic experiences into a more coherent narrative and sense of self.

Brainspotting, for example, uses focused mindfulness and bilateral stimulation to target the subcortical brain regions involved in trauma processing. By guiding individuals to focus on the somatic experience of trauma, Brainspotting can help to release “stuck” activation patterns and promote the integration of implicit and explicit memory systems.

EMDR, while often associated with cognitive processing, also targets subcortical networks through the use of bilateral stimulation and the activation of episodic memory fragments. The dual attention stimuli used in EMDR may help to “unfreeze” traumatic memories and allow for their integration into a more adaptive narrative.

Jungian analysis and parts-based therapies like IFS engage the imaginal realm and the archetypal dimensions of the psyche, which are deeply connected to subcortical networks and implicit memory systems. By working with active imagination, symbol, and the “felt sense” of different parts of the self, these approaches can facilitate the integration of dissociated experiences and the development of a more coherent sense of identity.

Somatic Experiencing, developed by Peter Levine, focuses on the body’s innate capacity to self-regulate and heal from trauma. By working with the felt sense of safety and danger in the body, and by facilitating the completion of incomplete defensive responses, Somatic Experiencing aims to release the “trapped energy” of trauma and restore healthy functioning to the autonomic nervous system.

The challenge for trauma therapists is to develop an integrative approach that honors the unique phenomenology of each individual’s experience while also targeting the relevant brain networks and memory systems. This requires a deep understanding of neuroscience, a sensitivity to individual differences, and a flexibility in adapting therapeutic interventions to the specific needs of each client.

Ultimately, the goal of trauma therapy is not merely symptom reduction but the restoration of a sense of agency, coherence, and connection in the wake of overwhelming experience. By working at the interface of neuroscience, phenomenology, and clinical practice, therapists can help clients to integrate the fragments of their traumatic past and to create a more embodied, authentic, and resilient sense of self.

As we continue to deepen our understanding of the neuroscience of trauma and its treatment, it is essential that we remain open to new paradigms and perspectives. The integration of insights from diverse fields – from cognitive neuroscience to depth psychology to somatic therapies – holds great promise for the future of trauma treatment. By honoring the complexity of the brain, the diversity of human experience, and the resilience of the human spirit, we can help to unlock the potential for healing and transformation that lies within each individual.

Integrating Neuroplausibility and Subjectivity in Psychotherapy Research

The push for greater integration of neuroplausible theories and subjective experiences in psychology reflects a growing recognition of the field’s complexity. While traditional notions of objectivity have been challenged by issues like the replication crisis and cultural biases, an emerging paradigm seeks to bridge the gap between biological mechanisms and lived realities.

Neuroplausible frameworks, such as those exploring how therapeutic techniques like Brainspotting may leverage neuroplasticity for trauma recovery, offer promising avenues for validating experiential interventions. By connecting abstract psychological constructs with distributed neural patterns, these approaches can provide a more comprehensive understanding of how the brain and mind interact to shape mental health.

However, embracing neuroplausibility does not mean abandoning methodological rigor. Instead, it calls for a more nuanced approach that acknowledges the inherent subjectivity of human experience while maintaining scientific standards. This may involve adopting practices like mitigated objectivity, which encourages researchers to transparently address their biases and cultural contexts, and reflexive science, which values diverse perspectives and documents researchers’ positionality.

To effectively integrate these principles into psychotherapy research, several adjustments may be necessary:

Balancing Quantitative and Qualitative Methods:

While quantitative studies remain essential for establishing statistical significance and generalizability, qualitative approaches can provide rich insights into the subjective experiences of clients and therapists. Mixed-methods designs that combine neuroimaging data with phenomenological interviews, for example, could yield a more holistic understanding of how interventions like Brainspotting work in practice.

Embracing Idiographic Approaches:

Traditional nomothetic research, which focuses on general laws and average responses, may overlook the unique factors that shape individual treatment outcomes. Idiographic methods, such as single-case designs and personalized neurofeedback protocols, can help capture the complex interplay between biological predispositions, environmental influences, and therapeutic processes for each client.

Collaborating Across Disciplines:

Integrating neuroplausible theories into psychotherapy research requires collaboration among neuroscientists, psychologists, and practitioners from various therapeutic traditions. Interdisciplinary teams can help bridge the gap between basic science and clinical application, ensuring that research findings are both biologically grounded and clinically relevant.

Prioritizing Ecological Validity:

Laboratory settings often fail to capture the real-world challenges and contextual factors that shape therapeutic outcomes. Conducting more research in naturalistic settings, such as community mental health centers and private practice offices, can help ensure that findings are applicable to the diverse populations and complex cases that therapists encounter in their daily work.

By embracing a more integrative approach that values both hard and soft science perspectives, psychotherapy research can develop a richer understanding of how interventions like Brainspotting work in practice. This paradigm shift may not only improve the effectiveness and accessibility of mental health treatments but also help bridge the gap between academic research and clinical practice.

Ultimately, the goal is to create a more inclusive and responsive scientific framework that honors the complexity of the human experience while advancing evidence-based practice. By bringing together insights from neuroscience, psychology, and the lived experiences of clients and therapists, we can develop a more comprehensive and compassionate approach to understanding and treating mental health issues.

Bibliography:

Gazzaniga, M. S. (2000). Cerebral specialization and interhemispheric communication: Does the corpus callosum enable the human condition? Brain, 123(7), 1293-1326.

Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence–from domestic abuse to political terror. Basic Books.

LeDoux, J. E. (1996). The emotional brain: The mysterious underpinnings of emotional life. Simon & Schuster.

Levine, P. A. (2010). In an unspoken voice: How the body releases trauma and restores goodness. North Atlantic Books.

MacLean, P. D. (1990). The triune brain in evolution: Role in paleocerebral functions. Springer Science & Business Media.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W. W. Norton & Company.

Schore, A. N. (2012). The science of the art of psychotherapy. W. W. Norton & Company.

Schwartz, R. C. (2021). No bad parts: Healing trauma and restoring wholeness with the internal family systems model. Sounds True.

Shapiro, F. (2017). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy: Basic principles, protocols, and procedures (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

0 Comments