Emil Bisttram Oversoul oil on masonite 1941

The Impact of Color on Somatics and Cognition: Insights from Emotional Transformation Therapy

Color plays a profound role in shaping our emotional experiences and cognitive processes. The therapy modality Emotional Transformation Therapy (ETT), pioneered by Dr. Steven Vazquez, delves into the intricate relationship between color, somatics, and cognition. By harnessing the power of color, ETT aims to facilitate emotional healing, promote self-awareness, and enhance overall well-being.

ETT recognizes that colors evoke specific emotional responses and somatic sensations. Each color on the spectrum is associated with distinct psychological and physiological experiences. Dr. Vazquez’s research has shed light on how different colors can be strategically utilized to activate desired emotions, process challenging feelings, and promote emotional regulation.

For more info on ETT check out our page, and the ETT homepage.

Readers can gain a deeper understanding of Dr. Vazquez’s contributions to the field of psychotherapy and the innovative ways in which he has integrated principles from neuroscience, ecology, and the creative arts to promote healing and transformation. These resources also highlight the potential for cross-disciplinary collaboration and the importance of considering the broader ecological and cultural contexts in which psychological distress and well-being are embedded.

As we continue to explore the frontiers of mind-body medicine and the role of color and visual stimulation in emotional healing, the work of Dr. Vazquez and other pioneers in this field can serve as a valuable guide and inspiration. By drawing on their insights and experiences, we can develop new approaches to therapy that are grounded in a deep respect for the complexity and diversity of human experience, and that harness the power of the natural world to promote resilience, creativity, and change.

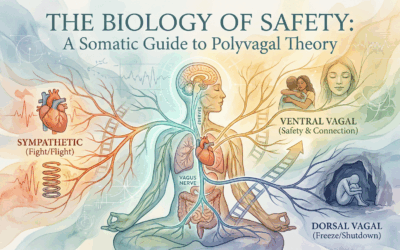

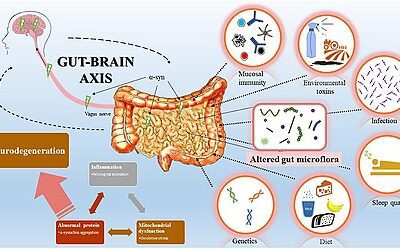

The Autonomic Nervous System and Color

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) plays a crucial role in regulating physiological processes and emotional responses. The ANS consists of two main branches: the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS). The SNS is responsible for the “fight or flight” response, activating the body’s resources to deal with perceived threats or challenges. The PNS, on the other hand, is associated with the “rest and digest” response, promoting relaxation, restoration, and healing.

In addition to the SNS and PNS, the polyvagal theory, developed by Dr. Stephen Porges, proposes a third branch of the ANS: the primitive parasympathetic nervous system (PPNS). The PPNS is associated with the dorsal vagal complex and is responsible for the “freeze” response, which can occur in situations of extreme stress or trauma.

Different colors have been shown to have specific effects on the ANS, activating either the SNS, PNS, or PPNS. By understanding these effects, therapists can use color strategically to promote desired physiological and emotional states.

ETT Colors

Violet: Trust and the Ventral Vagal Complex

Violet, the color of trust, is associated with the top of the skull, pineal gland, hypothalamus, cerebrospinal fluid, and coccyx. Exposure to violet can evoke a range of experiences, from paranoia and mistrust in the first phase to suspicion and an unyielding nature in the second phase. However, with continued violet stimulation and processing, individuals may reach a state of trust, accommodation, and appreciation.

Violet is associated with activation of the ventral vagal complex (VVC), a component of the PNS. The VVC is responsible for social engagement and connection, promoting feelings of safety, security, and trust. When the VVC is activated, individuals may experience a sense of calm, openness, and receptivity to others.

In ETT, violet is used to promote trust and social connection, helping individuals to feel safe and secure in their relationships. By stimulating the VVC, violet can help to reduce feelings of paranoia, mistrust, and suspicion, promoting a sense of openness and willingness to engage with others.

The evolutionary significance of violet’s impact on trust and the VVC is a subject of speculation. One hypothesis is that the ability to perceive and respond to violet light may have been advantageous for our ancestors in terms of detecting and interpreting social cues related to trust and bonding. The VVC’s involvement in promoting social engagement and connection could have been crucial for navigating complex social interactions, forming alliances, and ensuring survival within a group.

Moreover, the pineal gland and hypothalamus, which are associated with violet stimulation, play crucial roles in regulating circadian rhythms, hormone production, and emotional responses. The ability to regulate these functions in response to violet light could have served as an adaptive mechanism for maintaining physiological and emotional homeostasis, particularly in the context of social interactions and group dynamics.

From a developmental perspective, early experiences of trust and attachment can have a profound impact on an individual’s ability to form healthy relationships and regulate emotional responses. Exposure to nurturing and responsive caregiving, often associated with warm and soothing colors like violet, can promote the development of secure attachment styles and emotional resilience. In contrast, experiences of neglect, abuse, or inconsistent caregiving, often associated with harsh or threatening colors, can contribute to the development of insecure attachment styles and emotional vulnerability.

By working with violet in a therapeutic context, individuals can access and process early experiences related to trust and attachment, developing new, more adaptive patterns of relating and regulating emotions. This may involve visualizing violet light, engaging in trust-building exercises, or exploring the symbolic and metaphorical meanings of violet in the context of the individual’s unique history and experience.

QEEG:

Given the association of violet with the ventral vagal complex (VVC) and its role in promoting feelings of safety, security, and social engagement, we might expect to see increased activity in the alpha frequency band (8-12 Hz) in frontal and temporal regions, particularly on the right side. Alpha activity is often associated with relaxation, calm, and a sense of well-being. Additionally, we might observe increased coherence between frontal and temporal regions, reflecting enhanced communication and integration between these areas.

Somatic Region:

Violet stimulation is associated with activation in the coccyx region at the base of the spine. This region is often linked to feelings of safety, security, and trust in one’s environment and relationships. When the coccyx is activated, individuals may experience a sense of grounding, stability, and support, which can be particularly important in situations of stress or uncertainty.

Associated anatomy includes top of skull, pineal, hypothalamus, cerebrospinal fluid, and coccyx. Exposure can lead from paranoia, inability to trust, unyielding and suspicious to trusting, accommodating and appreciative. Violet activates the ventral vagal complex which promotes social engagement and feelings of safety and security. Evolutionarily, violet perception may have helped detect social cues related to trust and bonding.

Evolutionary Development:

The ability to perceive violet light is believed to have evolved relatively late in human history, as it requires the differentiation of subtle color variations at the shortest wavelengths of the visible spectrum. The pineal gland and hypothalamus, which process violet stimulation, are evolutionarily ancient structures that play crucial roles in regulating circadian rhythms, hormone production, and emotional responses. The development of these structures may have been influenced by the need to adapt to changing environmental and social conditions, particularly in terms of regulating physiological and emotional states in response to social cues and interactions.

Indigo: Understanding and the Prefrontal Cortex

Indigo, the color of understanding, is associated with the first through third cervical vertebrae. Exposure to indigo can evoke experiences ranging from an inability to think and obsessive thinking to disorganized thought and indecisiveness. With continued indigo stimulation and processing, individuals may achieve clarity, discernment, and a willingness to face their challenges.

Indigo is associated with activation of the prefrontal cortex (PFC), a region of the brain involved in higher-order cognitive functions such as attention, planning, and decision-making. The PFC is also involved in emotional regulation and the integration of cognitive and emotional processes.

In ETT, indigo is used to promote clarity of thought, discernment, and the ability to face one’s challenges. By stimulating the PFC, indigo can help to reduce obsessive thinking, disorganized thought, and indecisiveness, promoting a sense of mental clarity and purposeful action.

The evolutionary significance of indigo’s impact on understanding and the PFC is a topic of ongoing research. One hypothesis is that the ability to perceive and respond to indigo light may have been advantageous for our ancestors in terms of detecting and interpreting environmental cues related to problem-solving and decision-making. The PFC’s involvement in higher-order cognitive functions could have been crucial for navigating complex environments, adapting to changing circumstances, and making strategic decisions related to survival and reproduction.

Moreover, the PFC’s role in emotional regulation and the integration of cognitive and emotional processes may have been essential for maintaining social harmony and cooperation within groups. The ability to regulate one’s own emotions and understand the emotions of others could have facilitated the formation of social bonds, the resolution of conflicts, and the coordination of group activities.

From a developmental perspective, the PFC undergoes a prolonged period of maturation, continuing to develop well into adolescence and early adulthood. This extended developmental trajectory may be related to the complexity of the cognitive and emotional processes mediated by the PFC, as well as the need for flexibility and adaptability in response to changing environmental and social demands.

Exposure to enriching and stimulating environments, often associated with colors like indigo that promote curiosity and exploration, can support the healthy development of the PFC and related cognitive and emotional skills. In contrast, exposure to stressful or impoverished environments, often associated with colors that evoke feelings of confusion or overwhelm, can hinder the development of the PFC and contribute to cognitive and emotional difficulties.

By working with indigo in a therapeutic context, individuals can stimulate the PFC and related cognitive and emotional processes, developing greater clarity, discernment, and emotional regulation. This may involve engaging in problem-solving exercises, exploring different perspectives and viewpoints, or practicing mindfulness and self-reflection.

Somatic Region:

Indigo stimulation is associated with activation in the cervical spine region, particularly the upper neck. This region is often linked to mental clarity, intuition, and the ability to process complex information. When the upper neck is activated, individuals may experience a sense of mental alertness, focus, and insight, which can be particularly important when facing challenges or making difficult decisions.

Anatomy includes 1st-3rd cervical vertebrae. Can evoke inability to think, obsessive thinking, disorganized thought, indecisive, confrontive thinking before reaching clarity, discernment and willingness to face one’s challenges. Indigo activates the prefrontal cortex involved in higher-order cognitive functions like attention, planning and decision-making, as well as emotional regulation. Indigo perception may have helped interpret environmental cues for problem-solving and adapting to change.

Evolutionary Development:

The ability to perceive indigo light is believed to have evolved relatively late in human history, as it requires the differentiation of subtle color variations at shorter wavelengths. The cervical spine region, which is activated by indigo stimulation, has undergone significant changes throughout human evolution, supporting the development of upright posture, fine motor skills, and the ability to process and communicate complex ideas. The development of these capacities may have been influenced by the need to adapt to increasingly complex social and environmental demands, particularly in terms of problem-solving, decision-making, and emotional regulation.

QEEG:

Indigo’s association with the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and its involvement in higher-order cognitive functions such as attention, planning, and decision-making suggests that we might see increased activity in the beta frequency band (13-30 Hz) in frontal regions, particularly in the dorsolateral PFC. Beta activity is often associated with focused attention, problem-solving, and analytical thinking. We might also observe increased coherence between frontal and parietal regions, reflecting enhanced communication and integration between these areas.

Blue: Communication and the Broca’s Area

Blue, the color of communication, is associated with the fourth through seventh cervical vertebrae. Exposure to blue can evoke experiences ranging from quietness and shyness to garrulousness and verbal abusiveness. With continued blue stimulation and processing, individuals may develop appropriate communication skills, including the ability to disclose and express empathy.

Blue is associated with activation of the Broca’s area, a region of the brain involved in speech production and language processing. The Broca’s area is also involved in the regulation of emotions and the integration of language and affect.

In ETT, blue is used to promote effective communication, self-expression, and empathy. By stimulating the Broca’s area, blue can help to reduce verbal inhibition, shyness, and inattentiveness, promoting a sense of clarity, disclosure, and emotional attunement.

The evolutionary significance of blue’s impact on communication and the Broca’s area is a subject of ongoing research. One hypothesis is that the ability to perceive and respond to blue light may have been advantageous for our ancestors in terms of detecting and interpreting social cues related to communication and emotional expression. The Broca’s area’s involvement in language processing and emotional regulation could have been crucial for navigating complex social interactions, coordinating group activities, and maintaining social bonds.

Moreover, the development of language and communication skills may have been essential for the transmission of knowledge, cultural practices, and survival strategies across generations. The ability to effectively communicate ideas, emotions, and experiences could have facilitated the formation of shared narratives, values, and beliefs, which in turn could have supported the cohesion and resilience of social groups.

From a developmental perspective, the Broca’s area undergoes significant maturation during early childhood, in parallel with the development of language and communication skills. Exposure to rich linguistic environments, often associated with colors like blue that promote clarity and expressiveness, can support the healthy development of the Broca’s area and related language and communication abilities. In contrast, exposure to impoverished or inconsistent linguistic environments, often associated with colors that evoke feelings of inhibition or confusion, can hinder the development of these skills and contribute to communication difficulties.

By working with blue in a therapeutic context, individuals can stimulate the Broca’s area and related language and communication processes, developing greater clarity, expressiveness, and empathy. This may involve engaging in verbal exercises, practicing active listening and reflection, or exploring the emotional and symbolic meanings of language and communication.

Somatic Region:

Blue stimulation is associated with activation in the lower cervical spine region, particularly the throat and neck. This region is often linked to self-expression, communication, and the ability to speak one’s truth. When the throat and neck are activated, individuals may experience a sense of openness, fluidity, and authenticity in their communication, which can be particularly important when expressing emotions or conveying complex ideas.

4th-7th cervical, neck muscles, tonsils, vocal cords, neck gland, pharynx, nose, lips, mouth, Eustachian tube, cheeks, outer ear, teeth. Ranges from quiet, shy, talk – don’t talk, unattentive to garrulous, verbally abusive, hyperacusis before appropriate communication, disclosing, empathetic. Blue activates Broca’s area involved in speech, language and integration of language and affect. Blue perception likely aided detection of social communication cues.

Evolutionary Development:

The ability to perceive blue light is believed to have evolved relatively early in human history, as it falls within the middle of the visible light spectrum. The development of the larynx and vocal cords, which are innervated by nerves originating in the lower cervical spine, has been a crucial aspect of human evolution, enabling the development of complex language and communication skills. The evolution of these capacities may have been influenced by the need to coordinate group activities, maintain social bonds, and transmit knowledge and cultural practices across generations.

Qeeg:

Given the association of blue with the Broca’s area and its role in speech production and language processing, we might expect to see increased activity in the gamma frequency band (30+ Hz) in left frontal regions, particularly in the inferior frontal gyrus. Gamma activity is often associated with higher-order cognitive processes, including language and memory. Additionally, we might observe increased coherence between left frontal and temporal regions, reflecting enhanced communication and integration between these language areas.

Blue-Green:

Wholeness and the Insula Blue-green, the color of wholeness, is associated with the seventh cervical and first thoracic vertebrae. Exposure to blue-green can evoke experiences ranging from affective detachment and flat affect to emotional focus and hypersensitivity. With continued blue-green stimulation and processing, individuals may achieve affective self-awareness, emotional appropriateness, and an even-tempered nature.

Blue-green is associated with activation of the insula, a region of the brain involved in interoception (the perception of internal bodily states), emotional processing, and self-awareness. The insula is also involved in the integration of cognitive and emotional processes, promoting a sense of coherence and wholeness.

In ETT, blue-green is used to promote emotional self-awareness, appropriateness, and even-temperedness. By stimulating the insula, blue-green can help to reduce affective detachment, flat affect, and hypersensitivity, promoting a sense of emotional balance and integration.

The evolutionary significance of blue-green’s impact on wholeness and the insula is a topic of ongoing research. One hypothesis is that the ability to perceive and respond to blue-green light may have been advantageous for our ancestors in terms of detecting and interpreting internal bodily states and emotions. The insula’s involvement in interoception and emotional processing could have been crucial for maintaining physiological and emotional homeostasis, particularly in the context of changing environmental and social demands.

Moreover, the insula’s role in self-awareness and the integration of cognitive and emotional processes may have been essential for the development of a coherent sense of self and the ability to navigate complex social interactions. The capacity to differentiate between one’s own thoughts, feelings, and bodily states and those of others could have facilitated the formation of empathy, theory of mind, and social cognition.

From a developmental perspective, the insula undergoes significant maturation during early childhood and adolescence, in parallel with the development of emotional regulation and self-awareness skills. Exposure to nurturing and responsive environments, often associated with colors like blue-green that promote balance and integration, can support the healthy development of the insula and related emotional and self-awareness capacities. In contrast, exposure to neglectful or inconsistent environments, often associated with colors that evoke feelings of detachment or hypersensitivity, can hinder the development of these capacities and contribute to emotional difficulties.

By working with blue-green in a therapeutic context, individuals can stimulate the insula and related emotional and self-awareness processes, developing greater emotional balance, self-awareness, and coherence. This may involve engaging in mindfulness and body awareness exercises, exploring the relationship between thoughts, feelings, and bodily states, or practicing emotional regulation strategies.

Somatic Region:

Blue-green stimulation is associated with activation in the cervicothoracic junction, where the cervical and thoracic spine meet. This region is often linked to the integration of emotions and cognition, as well as a sense of overall well-being and wholeness. When the cervicothoracic junction is activated, individuals may experience a sense of balance, stability, and coherence, which can be particularly important when navigating complex emotional and cognitive experiences.

7th cervical, 1st thoracic, esophagus, trachea, forearms, hands, wrists, fingers, thyroid gland, shoulders, bursa in shoulders. Can lead from affectively detached, flat affect, logical to emotionally focused, moody, hypersensative before affectively self-aware, emotionally appropriate, even-tempered. Blue-green activates the insula involved in interoception, emotional processing and self-awareness. It may have helped maintain physiological and emotional homeostasis.

Evolutionary Development:

The ability to perceive blue-green light is believed to have evolved relatively late in human history, as it requires the differentiation of subtle color variations. The cervicothoracic junction, which is activated by blue-green stimulation, has undergone significant changes throughout human evolution, supporting the development of upright posture, respiratory control, and the integration of emotional and cognitive processes. The evolution of these capacities may have been influenced by the need to maintain physiological and emotional homeostasis, develop a coherent sense of self, and navigate increasingly complex social and environmental demands.

Qeeg:

Blue-green’s association with the insula and its involvement in interoception, emotional processing, and self-awareness suggests that we might see increased activity in the theta frequency band (4-8 Hz) in insular and anterior cingulate regions. Theta activity is often associated with emotional processing, memory, and a sense of inner focus. We might also observe increased coherence between insular and prefrontal regions, reflecting enhanced communication and integration between these areas.

Green: Assertiveness, Love and the Orbitofrontal Cortex

Green, the color of love, is associated with the second and third thoracic vertebrae, lungs, bronchial tubes, breast, heart, coronary arteries, sacrum, and third lumbar vertebra. Exposure to green can evoke experiences ranging from emptiness and despondency to sadness and loneliness. With continued green stimulation and processing, individuals may achieve a state of joyfulness, fulfilled affection, and a sense of being nurtured.

Green is associated with activation of the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), a region of the brain involved in emotional processing, decision-making, and social behavior. The OFC is also involved in the experience of reward and pleasure, promoting feelings of joy, fulfillment, and contentment.

In ETT, green is used to promote feelings of love, affection, and nurturance. By stimulating the OFC, green can help to reduce feelings of emptiness, despondency, and loneliness, promoting a sense of emotional connection and fulfillment.

The evolutionary significance of green’s impact on love and the OFC is a subject of speculation. One hypothesis is that the ability to perceive and respond to green light may have been advantageous for our ancestors in terms of detecting and interpreting social cues related to affection, bonding, and caregiving. The OFC’s involvement in emotional processing and social behavior could have been crucial for forming and maintaining social bonds, particularly in the context of parent-child relationships and pair bonding.

Moreover, the OFC’s role in the experience of reward and pleasure may have been essential for motivating behaviors related to caregiving, resource sharing, and social support. The capacity to derive joy and fulfillment from nurturing others and being nurtured in return could have facilitated the formation of cooperative and altruistic behaviors, which in turn could have supported the survival and thriving of social groups.

From a developmental perspective, the OFC undergoes significant maturation during early childhood, in parallel with the development of attachment and social-emotional skills. Exposure to nurturing and responsive caregiving, often associated with colors like green that promote feelings of love and affection, can support the healthy development of the OFC and related social-emotional capacities. In contrast, exposure to neglectful or inconsistent caregiving, often associated with colors that evoke feelings of emptiness or loneliness, can hinder the development of these capacities and contribute to attachment difficulties.

By working with green in a therapeutic context, individuals can stimulate the OFC and related social-emotional processes, developing greater capacity for love, affection, and nurturance. This may involve exploring early attachment experiences, practicing compassion and empathy, or cultivating a sense of emotional connection and fulfillment in relationships.

Somatic Region:

Green stimulation is associated with activation in the heart region, particularly the center of the chest. This region is often linked to unconditional love, compassion, and the ability to form deep emotional connections with others. When the heart region is activated, individuals may experience a sense of openness, warmth, and expansiveness, which can be particularly important when cultivating loving and nurturing relationships.

2nd-3rd thoracic, lungs, bronchial tubes, breast, heart, coronary arteries, sacrum, 3rd lumbar. Empty, despondent, aloof to sad, lonely, abandoned before joyful, fulfilled affection, nurtured. Green activates the orbitofrontal cortex involved in emotional processing, reward and social behavior. Green perception likely supported detection of cues related to affection, bonding and caregiving.

Evolutionary Development:

The ability to perceive green light is believed to have evolved relatively early in human history, as it falls within the middle of the visible light spectrum. The development of the heart and circulatory system has been a crucial aspect of human evolution, enabling the efficient distribution of oxygen and nutrients throughout the body and supporting the development of complex social and emotional bonds. The evolution of these capacities may have been influenced by the need to form and maintain cooperative and altruistic behaviors, derive joy and fulfillment from nurturing others, and support the survival and thriving of social groups.

Qeeg:

Given the association of green with the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and its role in emotional processing, reward, and social behavior, we might expect to see increased activity in the delta frequency band (0.5-4 Hz) in frontal regions, particularly in the medial OFC. Delta activity is often associated with emotional processing, motivation, and a sense of empathy and attunement with others. Additionally, we might observe increased coherence between frontal and limbic regions, reflecting enhanced communication and integration between these emotional processing areas.

Yellow-Green: Peace and the Anterior Cingulate Cortex

Yellow-green, the color of peace, is associated with the fourth thoracic vertebra, stomach, liver, solar plexus, blood, gallbladder, common duct, upper legs, top of the head, and feet. Exposure to yellow-green can evoke experiences ranging from internal conflict and stagnation to anger, sadness, and hatred. With continued yellow-green stimulation and processing, individuals may achieve a state of friendliness, compatibility, and acceptance.

Yellow-green is associated with activation of the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), a region of the brain involved in emotional regulation, decision-making, and conflict resolution. The ACC is also involved in the experience of empathy and compassion, promoting feelings of acceptance, forgiveness, and inner peace.

In ETT, yellow-green is used to promote feelings of peace, harmony, and acceptance. By stimulating the ACC, yellow-green can help to reduce internal conflict, stagnation, and hatred, promoting a sense of emotional resolution and compatibility.

The evolutionary significance of yellow-green’s impact on peace and the ACC is a topic of ongoing research. One hypothesis is that the ability to perceive and respond to yellow-green light may have been advantageous for our ancestors in terms of detecting and interpreting social cues related to conflict resolution, cooperation, and group harmony. The ACC’s involvement in emotional regulation and decision-making could have been crucial for navigating complex social interactions, resolving conflicts, and maintaining group cohesion.

Moreover, the ACC’s role in the experience of empathy and compassion may have been essential for promoting prosocial behaviors, such as forgiveness, reconciliation, and the formation of alliances. The capacity to understand and share the emotions of others, even in the face of conflict or disagreement, could have facilitated the resolution of interpersonal and intergroup tensions, supporting the stability and resilience of social groups.

From a developmental perspective, the ACC undergoes significant maturation during childhood and adolescence, in parallel with the development of emotional regulation and social cognition skills. Exposure to nurturing and responsive environments, often associated with colors like yellow-green that promote feelings of peace and acceptance, can support the healthy development of the ACC and related emotional and social capacities. In contrast, exposure to hostile or conflictual environments, often associated with colors that evoke feelings of anger or hatred, can hinder the development of these capacities and contribute to difficulties with emotional regulation and social functioning.

By working with yellow-green in a therapeutic context, individuals can stimulate the ACC and related emotional and social processes, developing greater capacity for peace, harmony, and acceptance. This may involve practicing conflict resolution skills, cultivating empathy and compassion, or exploring the roots of internal conflicts and how to resolve them.

Somatic Region:

Yellow-green stimulation is associated with activation in the solar plexus region, located in the upper abdomen. This region is often linked to personal power, self-esteem, and the ability to navigate social dynamics and maintain a sense of inner peace. When the solar plexus region is activated, individuals may experience a sense of confidence, assertiveness, and emotional resilience, which can be particularly important when facing conflicts or challenges in relationships or social situations.

4th thoracic, stomach, liver, solar plexus, blood, gall bladder, common duct, upper legs, top of head, feet. Can evoke internal conflicted, stagnated, perplexed to anger & sadness, adversarial, hateful before friendly, compatible, accepting. Yellow-green activates the anterior cingulate cortex involved in emotional regulation, decision-making and conflict resolution. It likely aided detection of cues related to conflict resolution and group harmony.

Evolutionary Development:

The ability to perceive yellow-green light is believed to have evolved relatively late in human history, as it requires the differentiation of subtle color variations. The solar plexus region, which is activated by yellow-green stimulation, plays a crucial role in the autonomic nervous system, regulating digestion, metabolism, and stress responses. The development of this region has been important for human evolution, enabling individuals to manage stress, maintain homeostasis, and engage in complex social interactions. The evolution of these capacities may have been influenced by the need to navigate increasingly complex social and environmental demands, resolve conflicts, and maintain group harmony and cohesion.

Qeeg:

Yellow-green’s association with the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and its involvement in emotional regulation, conflict resolution, and empathy suggests that we might see increased activity in the alpha frequency band (8-12 Hz) in midline frontal regions, particularly in the dorsal ACC. As mentioned earlier, alpha activity is often associated with relaxation, calm, and a sense of well-being. We might also observe increased coherence between the ACC and prefrontal regions, reflecting enhanced communication and integration between these regulatory areas.

Yellow: Hope and the Nucleus Accumbens

Yellow, the color of hope, is associated with the fifth and sixth thoracic vertebrae, adrenal glands, spleen, pancreas, duodenum, back of the neck, arms, and hands. Exposure to yellow can evoke experiences ranging from emotional paralysis and powerlessness to anger and frustration. With continued yellow stimulation and processing, individuals may achieve a state of calmness, empowerment, and hopefulness.

Yellow is associated with activation of the nucleus accumbens (NAcc), a region of the brain involved in reward processing, motivation, and goal-directed behavior. The NAcc is also involved in the experience of positive emotions such as joy, optimism, and hope.

In ETT, yellow is used to promote feelings of hope, empowerment, and motivation. By stimulating the NAcc, yellow can help to reduce emotional paralysis, powerlessness, and frustration, promoting a sense of agency, resilience, and positive expectancy.

The evolutionary significance of yellow’s impact on hope and the NAcc is a subject of speculation. One hypothesis is that the ability to perceive and respond to yellow light may have been advantageous for our ancestors in terms of detecting and interpreting environmental cues related to resource availability, such as ripe fruits or fertile soils. The NAcc’s involvement in reward processing and motivation could have been crucial for driving goal-directed behaviors, such as foraging or hunting, that supported survival and reproduction.

Moreover, the NAcc’s role in the experience of positive emotions may have been essential for maintaining a sense of optimism and resilience in the face of challenges or setbacks. The capacity to maintain hope and a positive outlook, even in difficult circumstances, could have facilitated the persistence and adaptability needed to overcome obstacles and achieve long-term goals.

From a developmental perspective, the NAcc undergoes significant maturation during adolescence and early adulthood, in parallel with the development of reward processing and goal-directed behavior skills. Exposure to stimulating and rewarding environments, often associated with colors like yellow that promote feelings of joy and motivation, can support the healthy development of the NAcc and related reward and motivation capacities. In contrast, exposure to deprived or stressful environments, often associated with colors that evoke feelings of powerlessness or frustration, can hinder the development of these capacities and contribute to difficulties with motivation and goal pursuit.

By working with yellow in a therapeutic context, individuals can stimulate the NAcc and related reward and motivation processes, developing greater capacity for hope, empowerment, and goal-directed behavior. This may involve setting and pursuing meaningful goals, cultivating a sense of agency and resilience, or exploring the sources of emotional paralysis and how to overcome them.

Somatic Region:

Yellow stimulation is associated with activation in the middle and lower back region, particularly the area of the adrenal glands. This region is often linked to stress response, resilience, and the ability to maintain a sense of hope and optimism in the face of challenges. When the adrenal region is activated, individuals may experience a sense of vitality, adaptability, and emotional stamina, which can be particularly important when pursuing long-term goals or navigating difficult circumstances.

5th-6th thoracic, adrenal glands, spleen, pancreas, duodenum, back of neck, arms, hands. Emotionally paralyzed, powerless, hopeless to anger, desire to fight, frustration before calm, empowered, hopeful. Yellow activates the hypothalamus which regulates physiological processes, sexual desire and intense emotions. Yellow perception may have supported pursuit of essential resources and social bonding.

Evolutionary Development:

The ability to perceive yellow light is believed to have evolved relatively early in human history, as it falls within the middle of the visible light spectrum. The development of the adrenal glands has been a crucial aspect of human evolution, enabling individuals to mount appropriate stress responses, adapt to changing environmental conditions, and maintain a sense of motivation and drive. The evolution of these capacities may have been influenced by the need to detect and respond to environmental cues related to resource availability, overcome obstacles and setbacks, and pursue long-term goals that supported survival and reproduction.

Qeeg:

Given the association of yellow with the nucleus accumbens (NAcc) and its role in reward processing, motivation, and positive emotions, we might expect to see increased activity in the theta frequency band (4-8 Hz) in deep subcortical regions, particularly in the ventral striatum. As noted earlier, theta activity is often associated with emotional processing, memory, and a sense of inner focus. Additionally, we might observe increased coherence between the NAcc and prefrontal regions, reflecting enhanced communication and integration between these motivational and regulatory areas.

Orange: Self-Esteem and the Temporoparietal Junction

Orange, the color of self-esteem, is associated with the seventh through tenth thoracic vertebrae, small intestines, lymphatic circulation, kidneys, ureters, heart, and throat. Exposure to orange can evoke experiences ranging from a lack of identity and fragmentation to negative self-perception and rebelliousness. With continued orange stimulation and processing, individuals may achieve a state of confidence, individuation, and independence.

Orange is associated with activation of the temporoparietal junction (TPJ), a region of the brain involved in self-other distinction, perspective-taking, and empathy. The TPJ is also involved in the experience of self-awareness and self-esteem, promoting feelings of confidence, individuation, and autonomy.

In ETT, orange is used to promote healthy self-esteem, self-expression, and assertiveness. By stimulating the TPJ, orange can help to reduce feelings of worthlessness, negative self-perception, and rebelliousness, promoting a sense of self-acceptance, authenticity, and independence.

The evolutionary significance of orange’s impact on self-esteem and the TPJ is a topic of ongoing research. One hypothesis is that the ability to perceive and respond to orange light may have been advantageous for our ancestors in terms of detecting and interpreting social cues related to status, dominance, and group hierarchies. The TPJ’s involvement in self-other distinction and perspective-taking could have been crucial for navigating complex social interactions, establishing one’s place within a group, and asserting one’s needs and interests.

Moreover, the TPJ’s role in the experience of self-awareness and self-esteem may have been essential for maintaining a sense of confidence and autonomy in the face of social pressures or challenges. The capacity to maintain a clear and positive sense of self, even in the face of criticism or opposition, could have facilitated the pursuit of individual goals and the expression of unique talents and abilities.

From a developmental perspective, the TPJ undergoes significant maturation during childhood and adolescence, in parallel with the development of self-awareness and social cognition skills. Exposure to supportive and validating environments, often associated with colors like orange that promote feelings of confidence and individuality, can support the healthy development of the TPJ and related self-awareness and social capacities. In contrast, exposure to critical or rejecting environments, often associated with colors that evoke feelings of worthlessness or fragmentation, can hinder the development of these capacities and contribute to difficulties with self-esteem and social functioning.

By working with orange in a therapeutic context, individuals can stimulate the TPJ and related self-awareness and social processes, developing greater capacity for self-esteem, self-expression, and assertiveness. This may involve exploring identity and values, practicing boundary-setting and communication skills, or cultivating a sense of self-acceptance and authenticity.

Somatic Region:

Orange stimulation is associated with activation in the abdominal region, particularly the area of the digestive organs. This region is often linked to self-worth, personal identity, and the ability to assert oneself in the world. When the abdominal region is activated, individuals may experience a sense of inner strength, self-reliance, and the courage to express their unique qualities and talents.

7th-10th thoracic, small intestines, lymph circulation, kidneys, ureters, heart, throat. Can lead from lack of identity, fragmented identity, worthlessness to negative self-perception, rebellious before confident, individuated, independent. Orange likely activates self-awareness and perspective-taking capacities.

Evolutionary Development:

The ability to perceive orange light is believed to have evolved relatively early in human history, as it falls within the middle of the visible light spectrum. The development of the digestive system has been a crucial aspect of human evolution, enabling individuals to extract nutrients from a wide range of food sources, support brain development, and maintain overall health and vitality. The evolution of these capacities may have been influenced by the need to navigate complex social hierarchies, assert one’s needs and interests, and maintain a sense of confidence and autonomy in the face of social pressures or challenges.

Qeeg:

Orange’s association with the temporoparietal junction (TPJ) and its involvement in self-other processing, perspective-taking, and self-awareness suggests that we might see increased activity in the beta frequency band (13-30 Hz) in right temporoparietal regions. As mentioned earlier, beta activity is often associated with focused attention, social cognition, and a sense of self. We might also observe increased coherence between the TPJ and prefrontal regions, reflecting enhanced communication and integration between these self-processing areas.

Red-Orange: Freedom and the Amygdala

Red-orange, the color of freedom, is associated with the eleventh and twelfth thoracic vertebrae, first and second lumbar vertebrae, appendix, abdomen, upper leg, large intestines, inguinal rings, trapezius, and shoulders. Exposure to red-orange can evoke experiences ranging from rigidity and inhibition to shame and excessive responsibility. With continued red-orange stimulation and processing, individuals may achieve a state of self-assuredness, carefreeness, and playfulness.

Red-orange is associated with activation of the amygdala, a region of the brain involved in emotional processing, threat detection, and stress response. The amygdala is also involved in the experience of fear, anxiety, and shame, which can limit one’s sense of freedom and autonomy.

In ETT, red-orange is used to promote feelings of freedom, spontaneity, and playfulness. By working with the amygdala, red-orange can help to reduce rigidity, inhibition, and excessive responsibility, promoting a sense of liberation, self-assuredness, and joyful engagement with life.

The evolutionary significance of red-orange’s impact on freedom and the amygdala is a subject of speculation. One hypothesis is that the ability to perceive and respond to red-orange light may have been advantageous for our ancestors in terms of detecting and interpreting environmental cues related to danger, such as predators or hostile social interactions. The amygdala’s involvement in threat detection and stress response could have been crucial for promoting vigilance, quick reactions, and the ability to mobilize resources in the face of potential harm.

Moreover, the amygdala’s role in the experience of fear, anxiety, and shame may have been essential for promoting social conformity and adherence to group norms. The capacity to experience and respond to these emotions could have facilitated the development of a sense of responsibility, duty, and the ability to regulate one’s behavior in accordance with social expectations.

From a developmental perspective, the amygdala undergoes significant maturation during early childhood, in parallel with the development of emotional regulation and stress response skills. Exposure to safe and supportive environments, often associated with colors like red-orange that promote feelings of freedom and playfulness, can support the healthy development of the amygdala and related emotional capacities. In contrast, exposure to threatening or punitive environments, often associated with colors that evoke feelings of rigidity or shame, can hinder the development of these capacities and contribute to difficulties with emotional regulation and stress management.

By working with red-orange in a therapeutic context, individuals can work with the amygdala and related emotional processes, developing greater capacity for freedom, spontaneity, and joyful engagement with life. This may involve exploring the roots of inhibition and excessive responsibility, practicing self-compassion and self-acceptance, or cultivating a sense of playfulness and creativity.

Somatic Region:

Red-orange stimulation is associated with activation in the lower thoracic and upper lumbar spine region, as well as the hips and thighs. This region is often linked to flexibility, adaptability, and the ability to move freely and express oneself authentically. When the lower thoracic and upper lumbar region is activated, individuals may experience a sense of fluidity, grace, and the courage to let go of rigid patterns of thought and behavior.

11th-12th thoracic, 1st-2nd lumbar, appendix, abdomen, upper leg, large intestines, inguinal rings, trapezius, shoulders. Can evoke rigid, inhibited, sacrificial to ashamed, enmeshed with others, excessive sense of responsibility before self-assured, carefree, playful. Red-orange seems to activate capacities for uninhibited self-expression.

Evolutionary Development:

The ability to perceive red-orange light is believed to have evolved relatively early in human history, as it falls within the longer wavelengths of the visible light spectrum. The development of the lower thoracic and upper lumbar spine region has been a crucial aspect of human evolution, enabling upright posture, bipedal locomotion, and the ability to engage in complex physical and social activities. The evolution of these capacities may have been influenced by the need to navigate complex and potentially threatening environments, respond quickly and flexibly to changing circumstances, and maintain a sense of freedom and autonomy while also adhering to social norms and expectations.

Qeeg:

Given the association of red-orange with the amygdala and its role in emotional processing, threat detection, and stress response, we might expect to see increased activity in the gamma frequency band (30+ Hz) in medial temporal regions, particularly in the amygdala. As noted earlier, gamma activity is often associated with higher-order cognitive processes, including emotional learning and memory. Additionally, we might observe increased coherence between the amygdala and prefrontal regions, reflecting enhanced communication and integration between these emotional processing and regulatory areas.

Red: Passion and the Hypothalamus

Red, the color of passion, is associated with the third, fourth, and fifth lumbar vertebrae, prostate, lower back muscles, sciatic nerve, sex organs, uterus, bladder, knees, back of the neck, and stomach. Exposure to red can evoke experiences ranging from boredom and aimlessness to hyperactivity and aberrant sexuality. With continued red stimulation and processing, individuals may achieve a state of passionate, sexually appropriate, and purposeful living.

Red is associated with activation of the hypothalamus, a region of the brain involved in the regulation of basic physiological processes such as hunger, thirst, and sexual desire. The hypothalamus is also involved in the experience of intense emotions such as passion, excitement, and aggression.

In ETT, red is used to promote healthy passion, sexuality, and purposeful action. By working with the hypothalamus, red can help to reduce boredom, aimlessness, and aberrant sexuality, promoting a sense of vitality, engagement, and clarity of purpose.

The evolutionary significance of red’s impact on passion and the hypothalamus is a topic of ongoing research. One hypothesis is that the ability to perceive and respond to red light may have been advantageous for our ancestors in terms of detecting and interpreting environmental cues related to mating and reproduction. The hypothalamus’s involvement in sexual desire and physiological arousal could have been crucial for promoting behaviors that supported the propagation of the species and the formation of pair bonds.

Moreover, the hypothalamus’s role in the regulation of basic physiological processes may have been essential for maintaining overall health and well-being, particularly in the face of changing environmental demands. The capacity to experience and respond to feelings of hunger, thirst, and sexual desire could have facilitated the pursuit of essential resources and the formation of social bonds that supported survival and thriving.

From a developmental perspective, the hypothalamus undergoes significant maturation during puberty, in parallel with the development of sexual and reproductive capacities. Exposure to appropriate sexual education and healthy relationship models, often associated with colors like red that promote feelings of passion and purpose, can support the healthy development of the hypothalamus and related sexual and reproductive capacities. In contrast, exposure to neglectful or abusive environments, often associated with colors that evoke feelings of boredom or aimlessness, can hinder the development of these capacities and contribute to difficulties with sexual and reproductive health.

By working with red in a therapeutic context, individuals can work with the hypothalamus and related physiological and emotional processes, developing greater capacity for healthy passion, sexuality, and purposeful living. This may involve exploring the roots of boredom and aimlessness, developing a sense of vitality and engagement, or cultivating healthy and fulfilling sexual relationships.

Somatic Region:

Red stimulation is associated with activation in the lower abdomen and pelvic region, particularly the area of the reproductive organs. This region is often linked to passion, desire, and the ability to channel sexual energy in a healthy and fulfilling way. When the lower abdomen and pelvic region is activated, individuals may experience a sense of aliveness, sensuality, and the courage to pursue their deepest desires and passions.

Evolutionary Development:

The ability to perceive red light is believed to have evolved very early in human history, as it falls within the longest wavelengths of the visible light spectrum. The development of the reproductive system has been a crucial aspect of human evolution, enabling the propagation of the species, the formation of pair bonds, and the ability to experience intense emotional and physical connections with others. The evolution of these capacities may have been influenced by the need to detect and respond to environmental cues related to mating and reproduction, maintain overall health and well-being, and form social bonds that supported survival and thriving.

Qeeg:

Red’s association with the hypothalamus and its involvement in regulating basic physiological processes, sexual desire, and intense emotions suggests that we might see increased activity in the delta frequency band (0.5-4 Hz) in deep subcortical regions, particularly in the hypothalamus. As mentioned earlier, delta activity is often associated with emotional processing, motivation, and autonomic regulation. We might also observe increased coherence between the hypothalamus and limbic regions, reflecting enhanced communication and integration between these physiological and emotional processing areas.

3rd-5th lumbar, prostate, lower back muscles, sciatic nerve, sex organs, uterus, bladder, knees, back of neck, stomach. Experiences range from bored, asexual, aimless to hyperactive, aberrant sexuality, desire to run/flee before passionate, sexually appropriate living and clarity of purpose. Red activates the hypothalamus and likely supported detection of cues related to mating and reproduction.

Far Red: Life Instinct and the Brainstem

Far red, the color of the life instinct, is associated with the sacrum, coccyx, rectum, anus, hip bones, buttocks, lower legs, ankles, feet, head, heart, and stomach. Exposure to far red can evoke experiences ranging from shock and depersonalization to hypersensitivity and preoccupation with death. With continued far red stimulation and processing, individuals may achieve a state of rootedness, security, and a strong desire to live.

Far red is associated with activation of the brainstem, a region of the brain involved in the regulation of basic survival functions such as respiration, heart rate, and arousal. The brainstem is also involved in the experience of primal emotions such as fear, rage, and terror, which can be activated in situations of extreme stress or trauma.

In ETT, far red is used to promote feelings of groundedness, security, and the will to live. By working with the brainstem, far red can help to reduce shock, depersonalization, and preoccupation with death, promoting a sense of embodiment, presence, and the desire to engage with life.

The evolutionary significance of far red’s impact on the life instinct and the brainstem is a subject of speculation. One hypothesis is that the ability to perceive and respond to far red light may have been advantageous for our ancestors in terms of detecting and interpreting environmental cues related to danger, such as blood or fire. The brainstem’s involvement in basic survival functions and primal emotions could have been crucial for promoting quick reactions, the ability to mobilize resources, and the will to live in the face of life-threatening situations.

Moreover, the brainstem’s role in the regulation of basic physiological processes may have been essential for maintaining overall health and well-being, particularly in the face of extreme stress or trauma. The capacity to maintain vital functions such as respiration and heart rate, even in the face of overwhelming emotions or physical sensations, could have facilitated the ability to survive and recover from traumatic experiences.

From a developmental perspective, the brainstem undergoes significant maturation during early infancy, in parallel with the development of basic survival and self-regulatory capacities. Exposure to safe and nurturing environments, often associated with colors like far red that promote feelings of security and groundedness, can support the healthy development of the brainstem and related survival capacities. In contrast, exposure to threatening or neglectful environments, often associated with colors that evoke feelings of shock or depersonalization, can hinder the development of these capacities and contribute to difficulties with self-regulation and trauma recovery.

By working with far red in a therapeutic context, individuals can work with the brainstem and related survival and self-regulatory processes, developing greater capacity for groundedness, embodiment, and the will to live. This may involve exploring the roots of shock and depersonalization, developing a sense of safety and security in the body, or cultivating a deep appreciation for the gift of life.

Somatic Region:

Far red stimulation is associated with activation in the sacral and coccygeal region, as well as the feet and lower legs. This region is often linked to instinctual drives, survival instincts, and the ability to feel grounded and connected to the earth. When the sacral and coccygeal region is activated, individuals may experience a sense of rootedness, stability, and the courage to face even the most challenging aspects of life.

Sacrum, coccyx, rectum, anus, hip bones, buttocks, lower legs, ankles, feet, head, hearg, stomach. Can lead from shock, depersonalized, meaninglessness to hyper sensory, survival insecurity, preoccupied with death before rooted, secure, desire to live. Far red seems to activate brainstem survival functions and the will to live, even in the face of life-threatening situations.

Evolutionary Development:

The ability to perceive far red light is believed to have evolved very early in human history, as it falls at the edge of the visible light spectrum and transitions into the infrared range. The development of the sacrum and coccyx has been a crucial aspect of human evolution, as these structures are remnants of the tail found in our early ancestors. The modification of these structures has enabled upright posture, bipedal locomotion, and the ability to sit comfortably for extended periods, which has been important for the development of human culture and society. The evolution of these capacities may have been influenced by the need to detect and respond to environmental cues related to danger and survival, maintain basic physiological functions in the face of stress or trauma, and develop a sense of groundedness and connection to the earth.

Qeeg:

Red’s association with the hypothalamus and its involvement in regulating basic physiological processes, sexual desire, and intense emotions suggests that we might see increased activity in the delta frequency band (0.5-4 Hz) in deep subcortical regions, particularly in the hypothalamus. As mentioned earlier, delta activity is often associated with emotional processing, motivation, and autonomic regulation. We might also observe increased coherence between the hypothalamus and limbic regions, reflecting enhanced communication and integration between these physiological and emotional processing areas.

Magenta: Integration and the Whole Brain

Magenta, as an extra-spectral color, is associated with the integration and harmonization of different brain networks and functions. Rather than being localized to a specific brain region, magenta is thought to promote whole-brain coherence and synchronization, facilitating the integration of cognitive, emotional, and physiological processes.

In ETT, magenta is used to promote feelings of safety, trust, and the capacity for mature, constructive pleasure. By working with the whole brain, magenta can help to reduce defensive or maladaptive patterns of response, promoting a sense of openness, flexibility, and the ability to engage with a wide range of emotional experiences in a healthy and adaptive way.

The evolutionary significance of magenta’s impact on whole-brain integration is a matter of conjecture. One hypothesis is that the ability to perceive and respond to magenta light may have been advantageous for our ancestors in terms of promoting cognitive flexibility, creativity, and the ability to adapt to changing environmental and social demands. The integration of different brain networks and functions could have been crucial for problem-solving, innovation, and the development of complex social and cultural practices.

Moreover, the capacity for whole-brain coherence and synchronization may have been essential for promoting overall health and well-being, particularly in the face of stress or challenge. The ability to integrate cognitive, emotional, and physiological processes in a harmonious and adaptive way could have facilitated the development of resilience, adaptability, and the capacity for growth and transformation.

From a developmental perspective, the ability to perceive and respond to magenta light may be related to the development of higher-order cognitive functions and the integration of complex sensory information in the brain. Exposure to stimulating and enriching environments, often associated with a wide range of colors and sensory experiences, can support the healthy development of whole-brain integration and related capacities for flexibility, creativity, and adaptability. In contrast, exposure to monotonous or deprived environments, often associated with a lack of color or sensory stimulation, can hinder the development of these capacities and contribute to difficulties with cognitive and emotional integration.

By working with magenta in a therapeutic context, individuals can work with the whole brain and related integrative processes, developing greater capacity for flexibility, adaptability, and the ability to engage with a wide range of emotional experiences in a healthy and mature way. This may involve exploring the roots of defensive or maladaptive patterns of response, developing a sense of safety and trust in the therapeutic relationship, or cultivating the capacity for constructive pleasure and enjoyment in life.

Somatic Region:

Magenta stimulation is not associated with a specific somatic region but may have a generalized effect on the body and brain. When the whole brain is stimulated by magenta light, individuals may experience a sense of integration, coherence, and the ability to engage with the full range of bodily sensations and emotional experiences in a grounded and centered way.

Evolutionary Development:

As magenta is an extra-spectral color, it does not have a specific evolutionary history. However, the ability to perceive and process magenta light may be related to the development of higher-order cognitive functions and the integration of complex sensory information in the brain. The evolution of these capacities may have been influenced by the need to adapt to changing environmental and social demands, promote cognitive flexibility and creativity, and develop complex social and cultural practices that supported survival and thriving.

Qeeg:

Magenta’s association with whole-brain integration and its potential to promote coherence and synchronization across different brain networks suggests that we might see increased global coherence across all frequency bands and brain regions. This would reflect enhanced communication and integration between various cognitive, emotional, and physiological processing areas, promoting a sense of unity, flexibility, and adaptability in the face of changing demands.

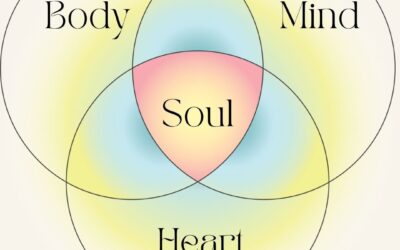

The Psychological Impact of Color:

While some of this information is readably observable and reproducible clinically and some has been developed or validated by research, parts are still speculative and would need to be tested empirically using qEEG and other neuroimaging methods. Additionally, individual responses to color stimulation may vary based on factors such as personal history, current emotional state, and cultural background. However, by considering the known functions and connectivity of the brain regions associated with each color, we can begin to generate testable hypotheses about the patterns of electrical activity that might be observed during Emotional Transformation Therapy and related approaches.

Through considering clinical findings, evolution and Qeeg studies, we can see how different colors may be associated with specific regions of the body and brain, and how these associations may be shaped by evolutionary and developmental factors.

By harnessing the power of color in a therapeutic context, individuals may be able to access and process deep-seated emotions, promote self-awareness and self-regulation, and experience profound shifts in cognitive and somatic experience. However, it is important to approach color therapy with caution and to recognize its limitations, as well as the complexity and variability of individual responses to color.

Ultimately, the relationship between color, somatics, and cognition is an ongoing area of exploration and discovery, one that holds great promise for our understanding of the mind-body connection and the potential for personal growth and transformation. As we continue to explore the impact of color on our lives, we may discover new ways to harness its power for healing, creativity, and the cultivation of a more vibrant and fulfilling existence.

Emil Bistram Creative Forces oil on canvas 1936

Bibliography

Berlucci, G., & Aglioti, S. (1997). The body in the brain: Neural bases of corporeal awareness. Trends in Neurosciences, 20(12), 560-564.

Blanke, O., Ortigue, S., Landis, T., & Seeck, M. (2002). Stimulating illusory own-body perceptions. Nature, 419(6904), 269-270.

Craig, A. D. (2003). Interoception: The sense of the physiological condition of the body. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 13(4), 500-505.

Decety, J., & Meyer, M. (2008). From emotion resonance to empathic understanding: A social developmental neuroscience account. Development and Psychopathology, 20(4), 1053-1080.

Fisher, H. E., Aron, A., & Brown, L. L. (2006). Romantic love: A mammalian brain system for mate choice. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 361(1476), 2173-2186.

Lanius, R. A., Bluhm, R., Lanius, U., & Pain, C. (2006). A review of neuroimaging studies in PTSD: Heterogeneity of response to symptom provocation. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 40(8), 709-729.

Likhtik, E., Pelletier, J. G., Paz, R., & Paré, D. (2005). Prefrontal control of the amygdala. Journal of Neuroscience, 25(32), 7429-7437.

Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the body: A sensorimotor approach to psychotherapy. W. W. Norton & Company.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W. W. Norton & Company.

Rauch, S. L., van der Kolk, B. A., Fisler, R. E., Alpert, N. M., Orr, S. P., Savage, C. R., Fischman, A. J., Jenike, M. A., & Pitman, R. K. (1996). A symptom provocation study of posttraumatic stress disorder using positron emission tomography and script-driven imagery. Archives of General Psychiatry, 53(5), 380-387.

Vazquez, S. R. (2008). Emotional transformation therapy: An interactive ecological psychotherapy. Jason Aronson.

Vazquez, S. R. (1994). Ekos: A visual meditation system for treating emotional disorders. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 24(4), 285-300.

Vazquez, S. R. (2001). The use of visual stimulation in the treatment of emotional disorders. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 31(2), 125-135.

Vazquez, S. R. (2005). Emotional transformation therapy. In A. Freeman, S. H. Felgoise, A. M. Nezu, C. M. Nezu, & M. A. Reinecke (Eds.), Encyclopedia of cognitive behavior therapy (pp. 167-171). Springer.

Vazquez, S. R. (2008). Emotional transformation therapy: An interactive ecological psychotherapy. Jason Aronson.

Vazquez, S. R. (2014). Accelerated ecological psychotherapy with couples. In K. Brandt, B. D. Perry, S. Seligman, & E. Tronick (Eds.), Infant and early childhood mental health: Core concepts and clinical practice (pp. 261-274). American Psychiatric Association Publishing.

Vazquez, S. R. (2020). A brain-based approach to multicultural psychotherapy. In M. Gallardo & B. McNeill (Eds.), Intersections of multiple identities: A casebook of evidence-based practices with diverse populations (pp. 215-232). Routledge.

Vazquez, S. R., & Foley, R. C. (2019). Emotional transformation therapy: Clinical applications. In S. Pritzker & M. Runco (Eds.), Encyclopedia of creativity (3rd ed., pp. 346-352). Academic Press.

Further Reading

Damasio, A. (2000). The feeling of what happens: Body and emotion in the making of consciousness. Mariner Books.

Gendlin, E. T. (1982). Focusing. Bantam Books.

Levine, P. A. (2010). In an unspoken voice: How the body releases trauma and restores goodness. North Atlantic Books.

Panksepp, J. (1998). Affective neuroscience: The foundations of human and animal emotions. Oxford University Press.

Porges, S. W. (2017). The pocket guide to the polyvagal theory: The transformative power of feeling safe. W. W. Norton & Company.

Siegel, D. J. (2001). The developing mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are. Guilford Press.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

0 Comments