The phenomenon of cults, a subject that has fascinated and alarmed society for decades, remains a critical area of study within psychology and sociology. The allure of cults can be traced back to the complex interplay of psychological manipulation, charismatic leadership, and the human quest for belonging. This article delves into the groundbreaking work of scholars such as Robert J. Lifton, Margaret Singer, Janja Lalich, Steven Hassan, Eileen Barker, David G. Bromley, and James T. Richardson, to explore the intricate psychology behind cults. These experts have significantly contributed to our understanding of how cults operate, recruit, and maintain control over their members, offering insights into the broader implications for society and individual well-being.

The phenomenon of cults, a subject that has fascinated and alarmed society for decades, remains a critical area of study within psychology and sociology. The allure of cults can be traced back to the complex interplay of psychological manipulation, charismatic leadership, and the human quest for belonging. This article delves into the groundbreaking work of scholars such as Robert J. Lifton, Margaret Singer, Janja Lalich, Steven Hassan, Eileen Barker, David G. Bromley, and James T. Richardson, to explore the intricate psychology behind cults. These experts have significantly contributed to our understanding of how cults operate, recruit, and maintain control over their members, offering insights into the broader implications for society and individual well-being.

Cults present a paradoxical proposition to potential members: the allure of individual freedom within a framework that ultimately demands the relinquishment of power to a central authority. This contradiction lies at the heart of the cultic appeal, drawing in individuals through the promise of personal liberation and fulfillment, only to gradually encroach upon their autonomy, leading to a cathartic surrender of power to the cult leader. Understanding this dynamic offers insight into the complex psychological and social mechanisms that make cults attractive to a wide range of individuals, including those who are logical, educated, intelligent, as well as powerful and wealthy.

The Illusion of Freedom and Personal Growth

Initially, cults often present themselves as bastions of individual freedom and enlightenment, offering a sanctuary from societal constraints and a platform for personal growth. This portrayal taps into a deep-seated desire for self-actualization and belonging, making the cult seem like a fertile ground for personal development and exploration. The emphasis on individual talents and potential can be particularly appealing, as it promises an environment where one’s abilities are recognized, valued, and nurtured.

However, this illusion of freedom serves as a bait for a more insidious process of control. As members become more deeply involved, the cult’s demands intensify, revealing a starkly different reality. What begins as voluntary participation gradually morphs into a system of psychological dependence, where autonomy is eroded in favor of the group’s collective will, often embodied in the absolute authority of the leader.

Attraction of Logical, Educated, and Intelligent Individuals

Contrary to the stereotype that only the vulnerable or weak-minded fall prey to cults, logical, educated, and intelligent individuals are frequently targeted and absorbed into these groups. This demographic is attractive to cults for several reasons. Firstly, their skills and competencies can be instrumental in furthering the cult’s objectives, whether through professional expertise, social influence, or financial resources. Secondly, the recognition and utilitarian use of these skills within the cult can provide a sense of validation and purpose that individuals may not find in mainstream society.

The sophisticated recruitment strategies of cults often play directly to the strengths and desires of such individuals, framing involvement as an opportunity to apply their intellect and abilities towards higher, often altruistic goals. This can be particularly enticing for those who feel underappreciated or stifled in their current professional or personal lives, as the cult purports to offer a community that values their contributions and intellect.

Catharsis for the Powerful and Wealthy

For individuals who wield significant power and wealth, cults provide a unique form of catharsis. The external world views these individuals as highly autonomous and influential, yet the burden of constant decision-making and control can be isolating and anxiety-inducing. Cults offer an escape from this burden, a place where the powerful can relinquish control and submit to the authority of another.

This surrender is often framed within the cult as a spiritual or emotional purification, a necessary step toward true enlightenment or salvation. The process can be deeply relieving for those accustomed to bearing heavy responsibilities, providing a space where they can unburden themselves and feel part of a community that ostensibly values spiritual over material wealth. Ironically, the act of giving up control to the cult leader becomes a source of liberation, freeing the individual from the pressures and anxieties associated with their power and status in the outside world.

Cult Scholars

Robert J. Lifton’s Framework of Thought Reform

Robert J. Lifton, a psychiatrist renowned for his studies on the psychology of totalism, identified key thought control mechanisms used by cults in his seminal work, “Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism.” Lifton’s analysis of Chinese re-education programs revealed how systematic manipulation strategies—such as milieu control, demand for purity, and the cult of confession—are employed to alter individuals’ perceptions and loyalties. These mechanisms are not only pivotal in understanding political indoctrination but also in dissecting the psychological underpinnings of cult dynamics.

Margaret Singer’s Coercive Persuasion

Margaret Singer, a clinical psychologist, extensively explored the concept of coercive persuasion in cults. Her book, “Cults in Our Midst,” illuminates the sophisticated recruitment and control tactics cults use, highlighting how these groups systematically break down individuals’ sense of self and reconstruct it in alignment with the cult’s ideology. Singer’s work underscores the vulnerability of individuals to such manipulation, irrespective of their background or intelligence.

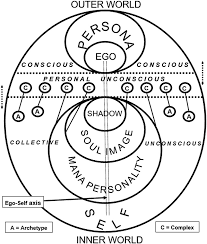

Janja Lalich and the Concept of Bounded Choice

Janja Lalich, a sociology professor, introduced the concept of “Bounded Choice” to explain how cults create environments where members believe they are making free choices, even when their options are severely limited by the group’s ideology and leadership. Lalich’s research into charismatic cults emphasizes the manipulative tactics that restrict personal autonomy, effectively trapping members in a cycle of dependency and conformity.

Eileen Barker’s Study of New Religious Movements

Eileen Barker, a sociology professor, has contributed significantly to the study of new religious movements and the nuanced understanding of cult membership. Her work, “The Making of a Moonie: Choice or Brainwashing?”, challenges simplistic narratives of cult involvement, suggesting that individuals join and remain in cults for complex reasons, including personal choice and social factors. Barker’s research highlights the diversity of experiences within cults and the importance of empirical investigation into religious movements.

Sociological Perspectives: Bromley and Richardson

David G. Bromley and James T. Richardson have further enriched the discourse on cults through their sociological analyses. Bromley’s work on the social construction of deviance offers insights into how society responds to new religious movements, often labeling them as cults without a nuanced understanding of their beliefs and practices. Richardson’s legal scholarship emphasizes the challenges faced by religious minorities in navigating societal and legal biases, advocating for a more balanced and informed approach to religious freedom.

Understanding and Addressing the Allure of Cults

The study of cults reveals a complex landscape of psychological manipulation, social influence, and the human search for meaning and belonging. The attraction of cults lies not in the naivety or weakness of their members, but in the sophisticated strategies of control and persuasion that exploit fundamental human desires and fears. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for developing effective interventions and supporting individuals in making informed choices about their involvement in such groups. As society continues to grapple with the challenges posed by cults, the work of Lifton, Singer, Lalich, Hassan, Barker, Bromley, and Richardson provides invaluable insights into the paths towards psychological autonomy and resilience.

Did you enjoy this article? Checkout the podcast here: https://gettherapybirmingham.podbean.com/

Bibliography:

Barker, E. (1984). The Making of a Moonie: Choice or Brainwashing?. Blackwell.

Bromley, D. G. (1998). The Politics of Religious Apostasy: The Role of Secular Authorities in the Promotion of Conversion from Religious Movements. Praeger.

Hassan, S. (1988). Combatting Cult Mind Control. Park Street Press.

Hassan, S. (2015). Freedom of Mind: Helping Loved Ones Leave Controlling People, Cults and Beliefs. Freedom of Mind Press.

Lalich, J. (2004). Bounded Choice: True Believers and Charismatic Cults. University of California Press.

Lifton, R. J. (1989). Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism: A Study of “Brainwashing” in China. The University of North Carolina Press.

Richardson, J. T. (1995). Minority Religions and the Context of Choice. Sociology of Religion, 56(2), 155-167.

Singer, M. T. (2003). Cults in Our Midst: The Continuing Fight Against Their Hidden Menace. Jossey-Bass.

Further Reading:

Bromley, D. G., & Shupe, A. D. (1981). Strange Gods: The Great American Cult Scare. Beacon Press.

Dawson, L. L. (1998). Comprehending Cults: The Sociology of New Religious Movements. Oxford University Press.

Festinger, L., Riecken, H. W., & Schachter, S. (1956). When Prophecy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of a Modern Group that Predicted the Destruction of the World. University of Minnesota Press.

Galanter, M. (1989). Cults: Faith, Healing, and Coercion. Oxford University Press.

Malinowski, B. (1922). Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

0 Comments