Understanding the Appeal of a Moral Panic

What was the Satanic Panic

The 1970s and 1980s saw a wave of moral hysteria known as the “Satanic Panic,” characterized by widespread fear of alleged Satanic cult activity. Despite a lack of evidence, many Americans became convinced that a vast, underground network of Satanists was responsible for everything from child abuse to human sacrifice. This essay will examine the social and psychological factors that made people vulnerable to these conspiracy theories, including changing religious demographics, economic uncertainty, and the psychodynamics of scapegoating. By understanding these factors, we can gain insight into the appeal of moral panics and the conditions that allow them to take hold.

The Cultural Context

To understand the Satanic Panic, it’s important to situate it within the broader cultural upheavals of the 1970s and ’80s. This was a period of profound social change, characterized by shifting values, economic volatility, and a sense of moral fragmentation.

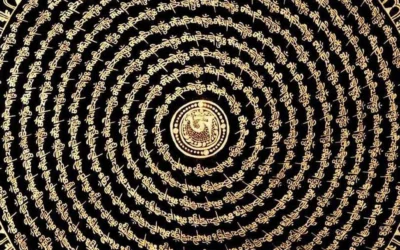

One key factor was the changing religious landscape. The post-war years had seen a steady decline in traditional religious observance, especially among young people. By the 1970s, alternative spiritualities, from New Age mysticism to neo-paganism, were on the rise, often syncretizing elements of Eastern religion and occultism. For many conservative Christians, this represented a worrying trend toward moral relativism and a dilution of traditional values.

At the same time, the era was marked by economic uncertainty and social instability. The oil crises of the 1970s, coupled with stagflation and the decline of manufacturing, created a sense of precarity and dislocation. The Cold War, with its specter of nuclear annihilation, added an undercurrent of existential dread. In this climate of unease, people were primed to look for scapegoats and simple explanations for their anxieties.

It was against this backdrop that the Satanic Panic took hold. For many, the idea of a shadowy Satanic conspiracy offered a compelling explanation for the perceived breakdown of traditional moral norms. If society seemed to be unraveling, it must be the work of diabolical forces working behind the scenes. This theory allowed people to project their fears onto an external evil, rather than grappling with the complex realities of social change.

The Psychodynamics of Paranoia

From a psychological perspective, the Satanic Panic can be understood as a form of collective paranoia, a defense mechanism against feelings of uncertainty and powerlessness. By constructing a narrative of a vast Satanic conspiracy, people were able to externalize their anxieties and feel a sense of moral righteousness in opposing it.

One key feature of paranoid thinking is its tendency toward confirmation bias-the selective attention to evidence that supports one’s preexisting beliefs. In the case of the Satanic Panic, even the most dubious accusations were often taken at face value, while skepticism was seen as evidence of complicity. This self-sealing logic insulated the conspiracy theory from disconfirmation, allowing it to metastasize in the face of contrary evidence.

Another important factor was the role of moral entrepreneurs-individuals and groups who stood to benefit from stoking the flames of the panic. These included religious leaders who saw the Satanic Panic as a way to reassert their moral authority, as well as law enforcement and mental health professionals who built careers on the prosecution of alleged Satanic crimes. By presenting themselves as experts on the supposed Satanic threat, they lent an air of credibility to the conspiracy theories.

The media also played a key role in spreading the panic. Sensationalist talk shows and news programs gave platforms to alleged “survivors” of Satanic cults, often without proper fact-checking or skeptical scrutiny. This created a feedback loop where the more the media covered the supposed Satanic threat, the more people came to believe in it, leading to further coverage and so on.

The Role of Religious Ideation

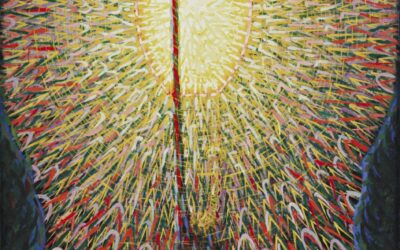

For many caught up in the Satanic Panic, the conspiracy theories took on a distinctly religious cast. The idea of a vast Satanic network plotting against Christianity fit neatly into a certain strain of apocalyptic theology that saw the modern world as a battleground between good and evil.

This Manichean worldview, which divided reality into absolute categories of light and darkness, was a key factor in the panic’s spread. It allowed people to frame their anxieties in cosmic terms, as part of an eternal struggle between God and the devil. By positioning themselves as soldiers in this spiritual war, they could feel a sense of purpose and moral clarity in the face of a complex and changing world.

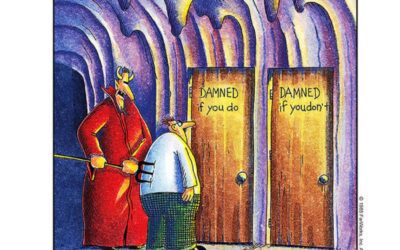

This religious framing also helps explain the panic’s resistance to disconfirmation. For true believers, the lack of evidence for Satanic crimes could be easily rationalized as proof of the conspiracy’s diabolical cunning. The more the claims were challenged, the more it could be taken as evidence of the dark forces attempting to suppress the truth. This kind of self-sealing logic is a common feature of conspiracy theories, but it takes on an especially intractable cast when wedded to religious conviction.

Scapegoating and Othering

At its core, the Satanic Panic was an exercise in scapegoating-the projection of social ills onto a demonized other. By blaming a shadowy cabal of Satanists for America’s problems, people were able to avoid grappling with the complex realities of social change and moral uncertainty.

This process of othering often took on a distinctly xenophobic and reactionary cast. The archetypal Satanist in the popular imagination was often associated with marginalized groups seen as threats to traditional values-from rock musicians to gay men to practitioners of alternative spiritualities. By positioning these groups as the enemy, the panic reinforced a conservative vision of normative identity.

In this sense, the Satanic Panic can be seen as a backlash against the social and cultural upheavals of the era. By projecting anxieties onto a folk devil, people were able to reassert a sense of moral order in the face of change. The irony, of course, is that in doing so they often ended up causing real harm to innocent people caught up in the hysteria.

The Satanic Panic’s Influence on Politics and Culture

The impact of the Satanic Panic was not limited to the immediate hysteria surrounding alleged cult activity. The conspiracy theories that fueled the panic also had a significant influence on political discourse and popular culture, shaping attitudes and policies in ways that reverberated long after the immediate crisis had passed.

On the political front, the Satanic Panic dovetailed with the rise of the religious right as a force in American politics. Conservative Christian groups like the Moral Majority saw the alleged threat of Satanism as a powerful rhetorical tool for mobilizing their base and pushing a traditionalist social agenda. By framing social ills like crime, drug use, and changing sexual mores as the result of a demonic influence, they were able to argue for a return to “traditional values” and a more muscular assertion of Christian morality in the public sphere.

This rhetoric found a receptive ear in the Reagan administration, which saw the religious right as a key part of its political coalition. Reagan himself spoke frequently of the struggle against “evil” in the world, a framing that resonated with the apocalyptic overtones of the Satanic Panic. More concretely, the administration’s “war on drugs” and tough-on-crime policies were often justified using the language of moral decay and demonic influence that had been popularized by the panic.

In the realm of popular culture, the Satanic Panic left a lasting mark on everything from horror films to heavy metal music. The figure of the Satanic cult leader became a stock villain in movies and television, often portrayed as a charismatic manipulator who preyed on the vulnerabilities of young people. This trope played into the larger cultural narrative of a society under siege by dark forces, a narrative that continues to shape our popular imaginaries to this day.

At the same time, the panic had a chilling effect on alternative spiritualities and subcultures that were seen as associated with Satanism. Practitioners of Wicca, neo-paganism, and other earth-based religions often found themselves the target of suspicion and harassment, as did fans of heavy metal music and role-playing games like Dungeons and Dragons. These groups were often portrayed as gateways to Satanic involvement, a framing that served to marginalize and demonize them in the public imagination.

The Legacy of the Panic: Lessons for Today

While the immediate hysteria of the Satanic Panic eventually faded, its legacy continues to shape our cultural and political discourse in complex ways. Many of the tropes and narratives that emerged during the panic – the idea of a society under siege by dark forces, the scapegoating of marginalized groups, the appeal to traditionalist values as a bulwark against moral decay – continue to resonate in our current moment.

Recognizing these parallels is important for understanding the appeal of conspiracy theories and the conditions that allow them to flourish. As with the Satanic Panic, these narratives often take root in times of social uncertainty and moral anxiety, when people are looking for simple explanations and clear enemies. They are fueled by a breakdown in trust in established authorities, and by the rise of alternative media ecosystems that can spread misinformation rapidly and without check.

Combatting these narratives requires more than just debunking specific claims – it requires addressing the underlying social and psychological conditions that make people vulnerable to them in the first place. This means working to build a more equitable and inclusive society, one where people feel a sense of security and belonging. It means fostering a media ecosystem that is committed to truth and accountability, and that works to build trust rather than exploit divisions. And it means cultivating the kind of critical thinking and media literacy skills that can help people navigate a complex and often confusing information landscape.

Other Cults and Conspiracy Theories

0 Comments