The architecture of our economic systems reveals far more than the movement of capital and commodities. Beneath the rational veneer of market mechanics lies a profound psychological infrastructure, one that Jung would recognize as the manifestation of collective shadow material projected onto the seemingly objective realm of finance. Our economic structures, far from being neutral mathematical constructs, serve as vast repositories for the repressed aspects of the collective psyche, creating what we might call a shadow economy that operates parallel to and often in contradiction with our conscious economic intentions.

The concept of the shadow, as Jung articulated in his groundbreaking work on the structure of the psyche, represents all that we have denied, repressed, or failed to integrate into our conscious self-image. When we examine modern financial systems through this lens, we discover that they function as elaborate mechanisms for managing collective psychological material that societies cannot consciously acknowledge. The International Monetary Fund’s research on financial crises reveals patterns of behavior that transcend mere economic calculation, suggesting deeper psychological forces at work in market dynamics.

Consider how poverty exists not merely as an economic condition but as a container for collective shadow projections. The poor become screens onto which societies project their fears of inadequacy, failure, and worthlessness. This projection serves a psychological function that extends beyond economic inequality. It allows those who have accumulated wealth to maintain their ego defenses against the terrifying possibility of their own vulnerability. The work of economist Thomas Piketty in Capital in the Twenty-First Century demonstrates how inequality perpetuates itself through mechanisms that appear rational but serve deeper psychological needs for hierarchy and differentiation.

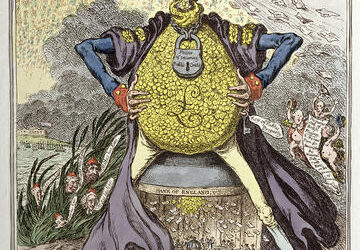

The phenomenon of economic bubbles provides perhaps the clearest example of shadow material erupting into collective consciousness. When we trace the psychological arc of any major financial bubble, from the Dutch tulip mania to the 2008 financial crisis, we observe a predictable pattern of shadow projection and eventual confrontation with repressed reality. During the inflation phase of a bubble, collective shadow material around scarcity, limitation, and mortality gets projected onto the inflating asset, which becomes imbued with quasi-magical properties. The asset represents not just wealth but transcendence of human limitation itself.

The behavioral economics research of Robert Shiller, particularly his work on irrational exuberance, illuminates how markets become theaters for collective psychological dramas. Yet even Shiller’s groundbreaking work stops short of recognizing the depth psychological dimensions of these phenomena. What appears as irrationality from an economic perspective reveals itself as profound psychological logic when viewed through a Jungian lens. The market is not failing to be rational; it is succeeding in being psychological.

Cryptocurrency emerges in this context not merely as a technological innovation but as a massive projection of shadow banking desires onto a new medium. The promise of decentralization carries the psychological charge of liberation from the father complex represented by central banks and governmental monetary authority. Yet in its actual manifestation, cryptocurrency has recreated many of the same power dynamics and inequalities it purported to transcend, suggesting that we are dealing with shadow projection rather than genuine transformation.

The blockchain technology underlying cryptocurrency serves as a fascinating case study in how technological systems become containers for psychological material. The immutable ledger represents a fantasy of perfect memory and accountability, a defense against the anxiety of forgetting and betrayal that haunts human economic relations. Yet this very immutability creates new forms of rigidity and potential trauma, as mistakes become literally irreversible. The research from MIT on blockchain psychology hints at these deeper implications without fully exploring their psychological dimensions.

Environmental costs represent another massive domain of economic shadow material. The externalization of environmental damage in economic calculations serves as a textbook example of collective repression. What cannot be consciously integrated into our economic self-concept gets literally expelled into the environment, where it accumulates as pollution, climate change, and ecological destruction. The Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change attempts to bring these costs into conscious economic calculation, yet the resistance to such integration reveals the powerful psychological forces maintaining this repression.

The concept of debt carries particularly rich psychological significance that extends far beyond its economic function. David Graeber’s anthropological work on debt reveals how obligation and guilt intertwine in the very etymology of debt across cultures. From a depth psychological perspective, debt represents a form of temporal shadow projection, where present desires cast shadows of obligation into the future. The modern debt economy has institutionalized this shadow dynamic, creating vast systems for managing the psychological burden of unfulfilled desire and deferred gratification.

Student debt, in particular, has become a container for intergenerational shadow material. Young people inherit not just financial obligations but the projected anxieties and unfulfilled dreams of previous generations. The Federal Reserve’s data on student debt shows numbers that transcend economic logic, suggesting we are dealing with a psychological phenomenon masquerading as an economic one. The debt serves to bind young people into a system that their elders fear they might otherwise reject or transform.

The phenomenon of tax havens and offshore banking reveals shadow dynamics operating at the intersection of individual and collective psychology. These financial structures serve not just to avoid taxation but to create psychological spaces outside the reach of collective consciousness. The Panama Papers investigation exposed not just financial impropriety but a vast shadow banking system that allows wealth to exist in a psychological state of exception, exempt from collective moral consideration.

Labor relations under capitalism demonstrate how economic structures serve to manage psychological splitting between different aspects of human experience. The division between workers and owners, between labor and capital, mirrors internal psychological divisions between different aspects of the self. The alienation that Marx identified in capitalist production can be understood as a form of collective dissociation, where aspects of creative potential become split off and projected onto the means of production themselves.

The gig economy represents a new evolution in this psychological splitting, where the fantasy of entrepreneurial freedom masks deeper forms of precarity and exploitation. Workers in the gig economy must maintain the psychological defenses of entrepreneurs while experiencing the material conditions of an increasingly vulnerable proletariat. This creates what we might call a trauma economy, where psychological survival depends on maintaining cognitive dissonance about one’s actual economic position. Research from the Economic Policy Institute on gig economy workers reveals patterns of stress and anxiety that suggest profound psychological costs beyond the economic impacts.

The financialization of everyday life has transformed even basic human needs into sites of shadow projection. Housing, healthcare, and education have become investment vehicles, carrying the projected shadows of scarcity and abundance, security and vulnerability. The home, once a symbol of psychological containment and safety, has become a financial asset whose value fluctuates with market psychology. This transformation has profound implications for how we experience basic security and belonging.

Insurance systems provide a particularly revealing window into economic shadow dynamics. The entire insurance industry exists to manage collective anxiety about uncertainty and loss. Yet the very existence of insurance creates new forms of moral hazard and psychological complexity. We pay to transfer risk, but in doing so, we also transfer psychological responsibility, creating systems where accountability becomes increasingly diffused and shadow material accumulates in the gaps between coverage and reality.

The stock market has evolved into a kind of collective nervous system, registering and amplifying psychological states across entire populations. High-frequency trading algorithms now operate at speeds that bypass conscious human cognition entirely, creating what we might think of as an automated unconscious that processes collective psychological material through mathematical operations. The work of researchers at the Santa Fe Institute on complexity in financial systems touches on these dynamics but rarely acknowledges their psychological dimensions.

Central banks have assumed a quasi-therapeutic role in managing collective economic psychology. The Federal Reserve’s communication strategies, forward guidance, and quantitative easing programs function less as mechanical economic interventions and more as forms of collective psychological management. The language of monetary policy has become increasingly psychological, with terms like “confidence,” “sentiment,” and “expectations” revealing the psychological reality beneath economic appearances.

The shadow of colonialism continues to structure global economic relations in ways that remain largely unconscious in mainstream economic discourse. The extraction of resources from the Global South to the Global North perpetuates patterns established during explicit colonialism, but now through financial mechanisms that obscure their psychological violence. Debt servicing, structural adjustment programs, and trade agreements serve to maintain psychological hierarchies that originated in colonial trauma. The UN Conference on Trade and Development reports document these patterns without fully acknowledging their psychological dimensions.

Tax policy serves as a site where collective shadow material around fairness, contribution, and entitlement gets negotiated. Progressive taxation attempts to address inequality, but the psychological resistance to such policies reveals deep shadow material around success, merit, and social obligation. The wealthy’s resistance to taxation often masks terror of their own dependency and vulnerability, while populist anti-tax movements project shadow material around authority and autonomy onto governmental structures.

The phenomenon of corporate personhood represents a fascinating form of collective projection where abstract legal entities become containers for human psychological material. Corporations assume personalities, have missions, and express values, yet they lack the psychological complexity and moral capacity of actual persons. This creates entities that can carry collective shadow projections while remaining immune to the psychological consequences that would constrain human actors.

Algorithmic trading and artificial intelligence in finance have created new forms of shadow dynamics where human psychological material gets encoded into mathematical systems that then operate autonomously. These systems carry the biases, fears, and desires of their creators but operate at scales and speeds that transcend human psychological processing. The research from the Alan Turing Institute on AI in finance reveals patterns that suggest we are creating technological unconscious systems that process collective shadow material in ways we don’t fully understand.

The emergence of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investing represents an attempt to integrate shadow material around corporate responsibility into investment decisions. Yet the rapid commercialization and gaming of ESG metrics reveals how quickly shadow material reconstellates around new structures. What begins as an attempt at integration becomes another site for projection and avoidance. The Harvard Business School research on ESG investing documents these dynamics without recognizing their psychological significance.

Inflation serves as a psychological phenomenon as much as an economic one, representing collective anxieties about value, stability, and the future. The fear of inflation often exceeds its actual economic impact, suggesting that it carries psychological significance beyond its material effects. Central banks’ obsession with inflation targeting reveals a kind of collective compulsion around maintaining psychological stability through price stability.

The informal economy, which operates outside official economic structures, serves as a literal economic unconscious where transactions occur outside the light of collective awareness. The International Labour Organization’s research suggests that the majority of the world’s workers operate in this shadow economy, yet it remains largely invisible to mainstream economic analysis. This informal sector serves crucial psychological functions, allowing for forms of exchange and relationship that the formal economy cannot acknowledge.

Bankruptcy law creates ritualized processes for managing the psychological crisis of economic failure. The legal structures around bankruptcy serve not just to reorganize debt but to manage the profound shame and shadow material activated by financial failure. The stigma attached to bankruptcy reveals how deeply economic success has become intertwined with ego identity in modern societies. Yet bankruptcy also offers a form of economic death and rebirth that can serve profound psychological transformation.

The commodity fetish that Marx identified takes on new meaning when viewed through a Jungian lens. Objects become imbued with psychological significance far exceeding their use value, serving as containers for projected aspects of the self. The luxury goods market, in particular, trades not in objects but in psychological states. A totem like a Hermès bag or a Rolex watch carries projected shadow material around worth, belonging, and transcendence of ordinary limitation.

Economic nationalism and trade wars reveal how collective shadow material gets projected onto other nations and economic systems. The foreign other becomes a screen for projecting economic anxieties and failures that cannot be consciously owned. China becomes a container for American anxieties about decline, while America serves a similar function for Chinese anxieties about legitimacy and respect. These projections structure global economic relations in ways that transcend rational economic calculation.

The welfare state emerged partly as an attempt to integrate shadow material around collective responsibility and vulnerability. Yet the psychological resistance to welfare programs reveals how threatening this integration remains to ego defenses built around individual success and autonomy. The OECD research on welfare states documents varying approaches across nations that reflect different collective psychological structures and shadow dynamics.

Pension systems create elaborate temporal structures for managing anxiety about aging and death. The promise of future security serves to defend against present anxieties, yet the increasing precarity of pension systems worldwide reveals the fragility of these psychological defenses. The shift from defined benefit to defined contribution pensions represents not just an economic change but a fundamental transformation in how societies manage collective anxiety about mortality and dependency.

The derivatives market has evolved into a kind of meta-economy where bets on bets create infinite recursive loops of abstraction. These financial instruments serve to distance economic actors from the psychological reality of their actions, creating what we might think of as a dissociative economy where cause and effect become increasingly disconnected. The Bank for International Settlements data on derivatives markets reveals a scale that suggests we are dealing with collective psychological phenomena rather than mere economic instruments.

Economic cycles themselves can be understood as collective psychological rhythms, with periods of expansion and contraction mirroring psychological patterns of inflation and deflation of ego defenses. The business cycle carries the psychological imprint of collective mood disorders, with manic phases of expansion followed by depressive contractions. The attempt to smooth these cycles through monetary and fiscal policy represents an attempt to manage collective psychological volatility.

The sharing economy initially promised to transform ownership patterns and create more communal forms of economic life. Yet its rapid commercialization and concentration into platform monopolies reveals how quickly shadow material reconstellates around new economic forms. What began as an attempt to transcend the shadow of ownership has created new forms of extraction and exploitation that serve the same psychological functions as traditional capitalism.

The concept of universal basic income represents an attempt to integrate shadow material around human worth and the right to existence independent of economic productivity. The psychological resistance to UBI reveals deep anxieties about meaning, purpose, and social hierarchy that economic systems serve to manage. The Finnish basic income experiment provided data suggesting psychological benefits beyond economic impacts, yet these findings have been largely ignored in economic debates.

In examining these shadow dynamics in our economic systems, we must recognize that integration rather than elimination is the path forward. The shadow cannot be banished; it can only be acknowledged and integrated into conscious awareness. This means developing economic structures that can hold psychological complexity rather than splitting it off into externalities and consequences.

The work ahead requires not just economic reform but psychological transformation at collective scales. We need economic systems that can acknowledge vulnerability without projecting it onto others, that can hold uncertainty without creating elaborate defenses against it, that can recognize interdependence without retreating into fantasies of independence. This is fundamentally psychological work that must happen alongside and through economic transformation.

As Jung understood, the confrontation with shadow material is always an invitation to growth and integration. Our economic shadows, projected onto financial systems and market dynamics, offer the same invitation at collective scales. The question is whether we have the courage to withdraw these projections and face the psychological realities they conceal. The future of our economic systems may depend less on technical innovation than on our capacity for this kind of collective psychological work.

0 Comments