The Wounded Healer: How Freud’s Trauma Shaped Modern Psychology

Understanding the Origins of Psychoanalysis Through the Lens of Its Founder’s Unresolved Wounds

The story of Sigmund Freud is not merely the biography of psychology’s most famous figure—it’s a cautionary tale about how unhealed trauma can shape an entire field of study. When we examine Freud’s life through a psychodynamic lens, we see how his personal wounds became the blueprint for psychoanalysis, ultimately creating a system that reflected his own psychological struggles rather than universal human truths.

The Formative Wound: A Father’s Submission

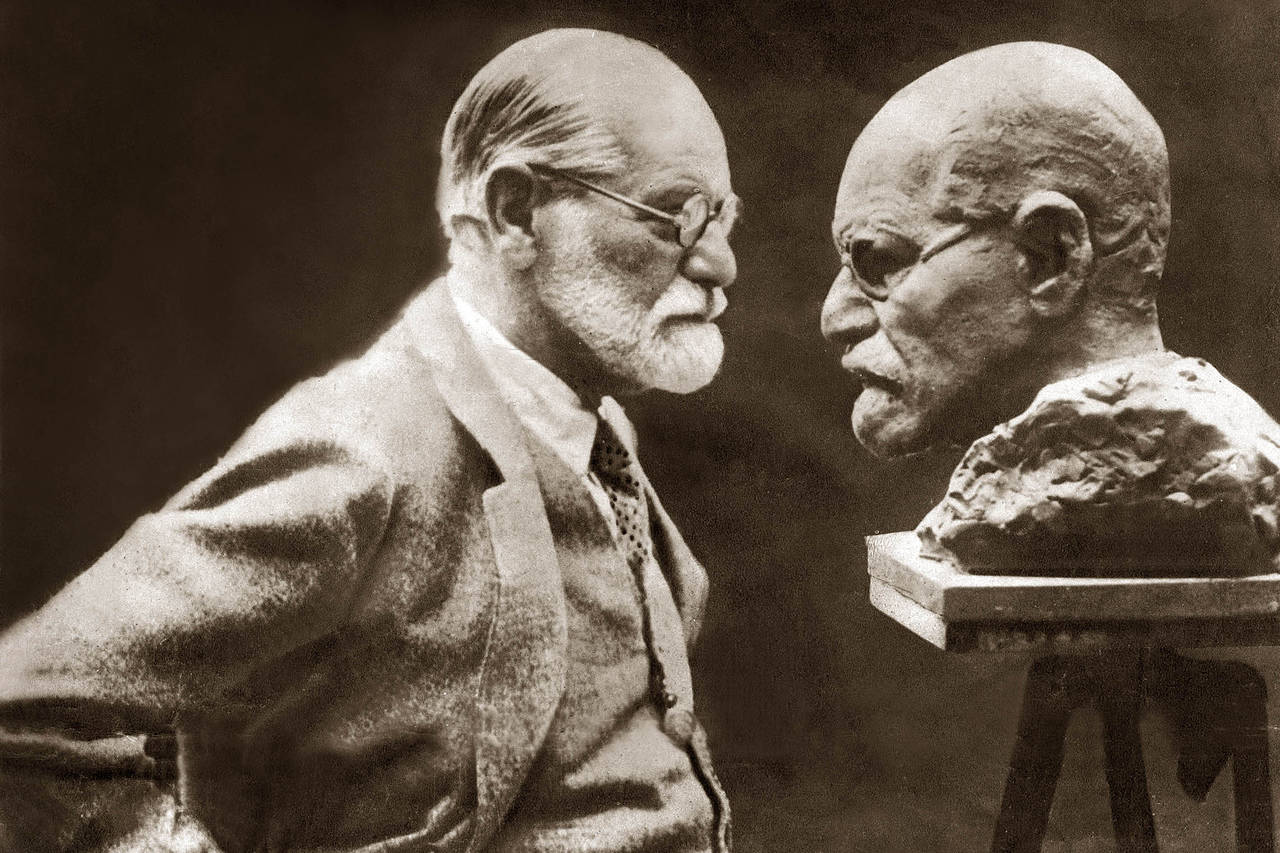

Vienna, 1866. Ten-year-old Sigmund Freud watches as anti-Semitic thugs knock his father’s hat into the mud and strike him. Jacob Freud picks up his hat, head down, and walks on without fighting back. This moment would haunt Freud for the rest of his life—not as tragedy, but as prophecy and metaphor that he would spend decades trying to escape.

From his father, Freud learned passivity, submission, and conflict avoidance. From his mother Amalia, he absorbed the belief that he was destined for greatness—her “golden boy” marked by the universe for revolutionary achievements. This created a fundamental psychological split: the need to be extraordinary while lacking the capacity to engage in direct confrontation.

The Hannibal Complex: Dreams of Conquest Without Battle

Freud identified deeply with Hannibal, the Carthaginian general who crossed the Alps but stopped at the gates of Rome, unable to take the final step toward victory. This became a recurring theme in Freud’s dreams—he could never enter Rome, symbolically representing his inability to claim the power and recognition he desperately sought.

In psychodynamic terms, we see how parental conditioning shapes our relationship to success and authority. Freud learned from his mother that greatness equaled love, but from his father, he absorbed the lesson that one must submit to superior forces rather than fight them. This created an internal conflict between grandiose ambitions and deep-seated passivity that would define his entire career.

The Cocaine Years: Escape and Self-Deception

Freud’s relationship with cocaine reveals the addictive patterns that often emerge when core wounds remain unaddressed. Beginning his research in 1884, Freud became convinced that cocaine was a miracle cure. When his colleague Carl Koller successfully used Freud’s suggestion about cocaine as a topical anesthetic for eye surgery—one of the decade’s biggest medical discoveries—Freud’s response was telling.

Rather than celebrating his contribution, Freud felt robbed and began spreading rumors that Koller had stolen the discovery from his notes. This pattern of initial collaboration followed by paranoid betrayal would repeat throughout his career. When several patients became addicted to cocaine and his friend Ernst von Fleiss died horribly from the treatment, Freud retreated from objective research forever.

This retreat into subjectivity wasn’t accidental—it was a psychological defense. After experiencing the shame of being wrong about something measurable, Freud created a system where he could never be proven wrong because everything became interpretation rather than empirical fact.

The Theater of Trauma: Learning from Charcot

In Paris at the Salpêtrière Hospital, Freud encountered Jean-Martin Charcot’s disturbing theatrical displays of traumatized women. Charcot would hypnotize these “hysteric” patients with electricity, blinding lights, and physical manipulation, making their symptoms appear and disappear for the entertainment of medical students. These women were kept against their will and continuously retraumatized for theatrical effect.

While Freud’s peers were disgusted by this abuse, Freud was mesmerized. He saw a technique that couldn’t be disproven and a power over the human mind that could be used to impress others. Critically, he observed patients describing childhood sexual abuse under hypnosis, planting the seeds for his later theories about repressed trauma.

The Birth of Free Association: Authority Without Accountability

Back in Vienna, Freud discovered that hypnosis was difficult when patients weren’t captive. So he invented something “better”—free association, a completely subjective technique where only Freud could decode the meaning, guaranteeing he would always be right.

Working with Joseph Breuer on the case of Anna O, Freud initially observed how patients experienced catharsis when expressing emotions about traumatic memories. However, when Breuer suggested that many wealthy Viennese families might be sexually abusing their children, Freud faced a choice: confront the powerful or protect himself.

Freud chose self-preservation, deciding instead that children were inherently sexual and invented abuse fantasies in their minds. This shift from believing survivors to blaming them marked a crucial turning point—not just in psychoanalytic theory, but in how trauma would be understood for generations.

The Pattern of Paternal Destruction

Throughout his career, Freud followed a consistent pattern with father figures and mentors. He would idealize them, extract what he needed, then destroy them when they threatened his authority or offered alternative perspectives. Joseph Breuer, who had lent Freud money and welcomed him into his home, was slandered as being “afraid of sexuality” when he refused to follow Freud into reductive sexual explanations for all psychological problems.

The case of Wilhelm Fliess represents perhaps the most disturbing example of this pattern. Fliess, a surgeon who believed that removing nasal bones could cure masturbation and all associated physical and emotional problems, appealed to Freud because his theories were similarly reductive and sexually focused. When Fliess left half a meter of surgical gauze in a patient’s nose after unnecessary surgery to “cure” her masturbation, nearly killing her seven times from blood loss, Freud defended the inexcusable incompetence rather than acknowledge his poor judgment in recommending such treatment.

The Secret Committee: Power Through Isolation

After learning that being the “son” in relationships left him vulnerable, Freud decided to only be the “father.” He collected brilliant disciples like Carl Jung, Otto Rank, and Alfred Adler, telling each they were his chosen successor. When they inevitably developed their own ideas, he cut them off for “disloyalty.”

By the time Freud established his practice in New York, only the “talentless and obsequious” remained. He created a “secret committee,” giving members golden rings with sexually symbolic cameos, modeled after secret societies. This group would meet in shadows, plotting against anyone who deviated from Freudian doctrine and literally destroying the careers of patients and providers who disagreed with them.

The Manipulation of Patients: Trauma as Business Model

One of the most disturbing aspects of Freud’s later practice was his direct manipulation of patients for financial gain. Needing funding for his institute, he convinced patient Horace Frink to divorce his wife and marry another wealthy patient, claiming that resistance would make him “latently homosexual” and psychotic. When Frink protested that he wasn’t gay, Freud insisted he was “triple secret super gay” but unconscious of it.

The manipulation worked—Frink’s guilt drove him psychotic, and he died believing his bathtub was a grave and his wife was a pig. Freud’s response revealed his true attitude toward patients: “We do analysis for two reasons: to understand the unconscious and to get paid.” Later, he wrote that “patients are a rabble, only good to provide us with a livelihood and material to learn from.”

The Case of Little Hans: Sexuality as Universal Explanation

Freud’s analysis of “Little Hans,” a five-year-old afraid of horses after witnessing one fall and nearly trample its rider, perfectly illustrates his reductive approach. Rather than seeing a normal childhood fear response to witnessing potential danger, Freud concluded that Hans wanted to kill his father and have sex with his mother. The horse represented the father because it had hair resembling the father’s mustache, and Hans’s fear represented castration anxiety because he knew horses lose their penises when castrated.

This case study reveals how Freud’s system could transform any normal human experience into evidence for his sexual theories, regardless of how unintuitive, unscientific, or potentially harmful such interpretations might be to the patients involved.

The Projection of Personal Trauma

Murray Stein’s observation that “Freud mistook mechanism for meaning” captures the fundamental flaw in psychoanalytic theory. Unable to see or face his own trauma, Freud projected it onto everyone else—first as a son seeking to overthrow inadequate fathers, then as a father defending against imaginary death wishes, and finally as a King Lear figure playing God with human minds.

Freud’s real discovery was that the unconscious exists as a realm of trauma, drives, archetypes, and intuitive creativity. However, he could only see sex and aggression as the forces lying dormant under society because Freudian psychology became very good at describing Freud’s own psychology, where repressed obsessions with sex and power dominated his inner life.

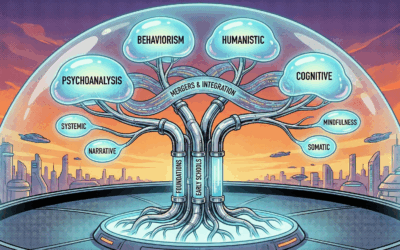

The Legacy: Understanding Modern Psychological Defenses

The defense mechanisms Freud embodied continue to operate in modern therapeutic and cultural contexts:

Blame-shifting: “You caused me to do that” Gaslighting: “You don’t understand how these things fit together like I do” Minimizing: “How can I apologize unless you’re perfect too?” Victim stance: “No one understands my unique combination of power and powerlessness” Intellectualization: Using complex theories to avoid emotional reality Splitting: Seeing people as all good or all bad based on their loyalty

Implications for Modern Practice

Understanding Freud’s story offers crucial insights for contemporary therapists:

- The Wounded Healer Dynamic: Unprocessed therapist trauma can become the lens through which all client issues are interpreted

- Authority vs. Collaboration: The difference between using therapeutic authority to heal versus to maintain power and control

- Projection in Practice: How therapists’ unresolved conflicts can be projected onto clients through interpretation and treatment planning

- The Importance of Supervision: Regular consultation helps identify when personal issues are interfering with clinical judgment

- Empirical Grounding: The danger of creating unfalsifiable theoretical systems that protect the therapist’s ego rather than serve client healing

The Continuing Relevance

Freud’s story remains relevant because it illustrates how easily the helping professions can become vehicles for perpetuating rather than healing trauma. His belief in his own victimhood justified his manipulation and abuse of others—a dynamic still visible in therapeutic relationships where the therapist’s need to be right supersedes the client’s need to be heard and healed.

The tragedy isn’t that Freud was wounded—most healers are. The tragedy is that he spent his life running from those wounds rather than facing them, creating a system that would influence psychology for over a century while reflecting his personal pathology rather than universal truths about human nature.

Conclusion: The Unfinished Journey to Rome

In his later work “Moses and Monotheism,” Freud continued to explore themes of corrupted fathers in religion, politics, and families, positioning himself as the perfect father who could lead others to the promised land. Yet even in his dreams, he never could enter Rome—the symbol of the power and recognition he desperately sought but felt unable to claim directly.

The question for modern practitioners is whether we will learn from Freud’s example: Will we face our own wounds honestly, or will we, like him, create elaborate systems that allow us to remain hidden while claiming to help others heal? The choice between authentic healing and sophisticated hiding continues to define not just individual therapeutic relationships, but the entire field of mental health.

Perhaps the most important lesson from Freud’s life is that the very wounds that drive us to become healers are the ones we must face most honestly. Only by doing our own work can we hope to truly serve others in theirs.

0 Comments