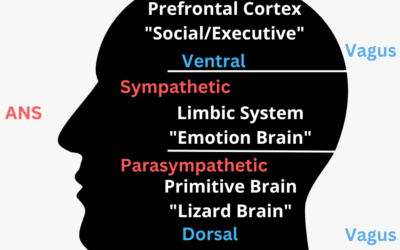

A neurobiological argument for the dominance of afferent feedback in emotional persistence and the therapeutic implications for trauma treatment

What Happens if You Delete a Psychotherapy Note: The Therapist’s Ultimate Guide to Correcting Clinical Notes:

A comprehensive guide for psychotherapists on the legal and ethical way to correct errors in clinical notes. Learn the difference between progress notes and psychotherapy notes, and the exact protocols for fixing typos, addendums, and “wrong patient” errors without violating HIPAA.

Psychotherapy Ethics Conflicts: When Insurance, Liability, and Patient Care Collide

Explore the complex ethical conflicts psychotherapists face when insurance requirements, professional liability concerns, and patient care standards collide. Learn how state laws affect out-of-network providers, understand documentation dilemmas, and discover best practices for navigating competing ethical demands in mental health practice. Essential reading for therapists, counselors, and mental health professionals managing the three-way bind of modern clinical practice.

Did the State of Alabama Just Get Rid of Ketamine Therapy for PTSD?

Alabama’s new ketamine therapy guidelines reflect critical questions about treating trauma. A Hoover therapist examines why dissociative patients often worsen with ketamine, compares it to EMDR and brainspotting, and explores the limitations of research in understanding trauma recovery.

The Alchemical Marketplace: Prima Materia to Gold in Consumer Psychology

The marketplace has always been a site of transformation, but under capitalism, it has become an alchemical laboratory where base matter undergoes psychological transmutation into objects of desire. Jung's lifelong fascination with alchemy was not mere historical curiosity but recognition that alchemical symbolism encoded profound psychological truths about transformation processes. When we examine modern consumer psychology through this alchemical lens, we discover that marketing and branding serve as...

The Archetype’s in Brand Psychology: Building Authentic Identity Through Jung’s Timeless Wisdom

Discover how Jung’s Jester archetype and the 12 archetypal patterns transform brand identity, from therapy practices to Fortune 500 companies. Learn practical strategies for authentic archetypal branding that bridges ancient wisdom with modern neuroscience.

The Complete Alabama LPC Licensing Guide:

Everything You Need to Know About ALC, LPC, and Private Practice Professional counseling in Alabama operates under a two-tiered licensing system overseen by the Alabama Board of Examiners in Counseling (ABEC), requiring all counselors to begin as Associate Licensed Counselors (ALCs) before progressing to Licensed Professional Counselor (LPC) status. This pathway involves earning a master's degree in counseling from a qualifying school that includes a practicum and internship, passing the National Counselor...

Joseph LeDoux and the Revolution in Trauma Therapy:

Understanding Memory Reconsolidation and the Neuroscience Behind Experiential Healing A Paradigm Shift in Understanding Emotional Memory For decades, the field of psychology operated under the assumption that emotional memories, particularly traumatic ones, were indelible marks on the psyche—permanent scars that could perhaps be managed but never truly erased. Joseph LeDoux, a pioneering neuroscientist at New York University, has fundamentally challenged this view through his groundbreaking research on the...

The Brain-Boosting Power of Vitamins: How Hardy Daily Essentials Nutrients Supports Mental Wellness

What supplements have an evidence basis to effect mental health? When it comes to optimizing our mental health and cognitive function, we often focus on lifestyle factors like exercise, sleep, and stress management. While these are undoubtedly important, we may overlook another crucial piece of the puzzle: nutrition. The food we eat provides the building blocks for our brains and bodies to function at their best. And when it comes to packing in a wide array of brain-boosting nutrients, few supplements can match...

New Frontiers in Brain-Based Therapies for Trauma

What are Newer Brain-Based Therapies for Trauma? In recent years, there has been a surge of interest and research into novel therapies that target the brain and nervous system to treat the effects of psychological trauma. These emerging approaches leverage new insights from neuroscience to heal trauma in ways that go beyond traditional talk therapy. By working with the brain and body, they aim to resolve trauma stored in the nervous system and transform painful memories. This article will explore several of the...

The Architecture of Sleep: Understanding the Neurobiology, Evolution, and Therapeutic Implications

Why do we Sleep? Sleep is a fundamental biological process that is essential for the health and well-being of all mammals, including humans. Despite its ubiquity and importance, sleep remains one of the most mysterious and poorly understood aspects of our lives. In this article, we will explore the complex architecture of sleep, including its neurobiology, evolution, and therapeutic implications. We will examine the different stages of sleep, the role of dreams in Jungian analysis, and the various ways in which...

How Alabama’s New Laws Could Affect Therapists

What Do Alabama's Abortion Laws Mean for Therapists and Mandated Reporters? Recent changes to Alabama’s abortion laws have significantly altered the legal landscape surrounding reproductive rights, particularly in redefining personhood to include embryos and fetuses at all stages of development. This could have far reaching implications for how anyone providing or recieving mental health care. What is Mandated Reporting? Mandated reporting laws require certain professionals, including therapists, to report...

Can Psychotherapy Survive Staying Seperated from Anthropology and Philosophy?

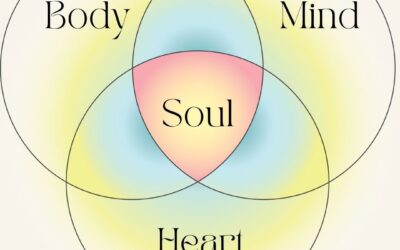

Should Psychotherapy Ponder the Mysteries of Philosophy and Anthropology? The specialized and fragmented nature of modern psychology has led to an abstracted and decontextualized view of the self, one that is disconnected from the embodied, embedded, and enactive dimensions of human experience. By drawing upon the insights of anthropology, philosophy, and the study of ancient religious traditions, we can begin to re-imagine psychology as a more holistic and integrative discipline, one that recognizes the deep...

Bipolar Disorder and ADHD:

Navigating the Complexity of Dual Diagnosis What is Bipolar Disorder with ADHD? Bipolar Disorder and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) are two distinct neurodevelopmental conditions that can co-occur in some individuals. Recent research suggests that up to 20% of individuals with bipolar disorder also meet criteria for ADHD, and vice versa. When someone has both bipolar disorder and ADHD, it creates a unique neurological profile that we'll refer to as bipolar-ADHD. The Diagnostic Evolution of...

Sensory Processing Disorder with Autism and ADHD:

Navigating a Multi-Sensory World What is SPD with Autism and ADHD? Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD), Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) are distinct neurodevelopmental conditions that can co-occur. When an individual experiences all three, we refer to this unique neurological profile as SPD-Autism-ADHD. The Diagnostic Evolution of SPD-Autism-ADHD Historically, sensory issues were often seen as a component of autism or ADHD rather than a distinct condition. Recent...

Borderline Personality Disorder and Bipolar Disorder:

Navigating Emotional Intensity What is BPD with Bipolar Disorder? Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) and Bipolar Disorder are distinct conditions that can co-occur in some individuals. Studies suggest that up to 20% of individuals with BPD also meet criteria for Bipolar Disorder. When someone has both BPD and Bipolar Disorder, it creates a unique psychological profile that we'll refer to as BPD-Bipolar. The Diagnostic Evolution of BPD-Bipolar Historically, the intense mood swings seen in BPD were often...

Unraveling the Neurobiology of Shame and Its Transformative Potential

The Roots of Emotion At the core of our emotional landscape lies a powerful and often misunderstood force: shame. As a fundamental human emotion, shame has deep evolutionary roots and profound impacts on our mental and physical well-being. By exploring the neurobiological processes underlying shame and its potential for transformation, we can gain valuable insights into the inner workings of our psyche and unlock pathways to emotional healing. The Neurobiology of Shame Recent studies have shed light on the...

Frequently Asked Questions About Brainspotting Therapy

F.A.Q. about Brainspotting What is Brainspotting? Brainspotting is an innovative psychotherapy approach that uses specific eye positions to access unprocessed trauma in the subcortical brain (Grand, 2013). It was developed by Dr. David Grand in 2003 as an offshoot of EMDR therapy. How does Brainspotting work? Brainspotting works by using focused eye positions to access survival-based subcortical parts of the brain like the amygdala that are often inaccessible through talk therapy alone (Grand, 2013). The...

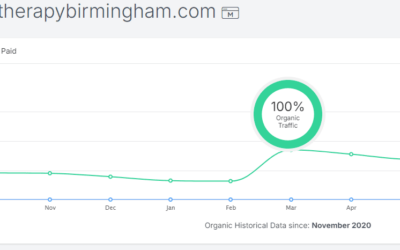

SEO for Therapists: How Therapists Can Rank Better on Google

How to Optimize Your Therapy Website for Google As a therapist in private practice, attracting new clients is essential for growing your business. With more and more people searching for mental health services online, having a strong digital presence is crucial. However, simply having a website isn't enough. To get in front of potential clients, you need to optimize your site for search engines like Google. This is where Search Engine Optimization (SEO) comes in. SEO is the process of improving your website's...

Unraveling the Enigma of Trauma and the Supernatural: Alex Monk’s Groundbreaking Work in Psychotherapy

A Pioneering Exploration of the Psyche's Hidden Realms In an enthralling podcast episode, psychotherapist and author Alex Monk takes listeners on a captivating journey through the uncharted territories of the human psyche. Drawing upon his trailblazing book "Trauma and the Supernatural in Psychotherapy," Monk introduces a revolutionary framework for understanding the intricate entanglement of relational trauma, unconscious phantasies, and supernatural experiences. His work invites clinicians to venture beyond the...

Looking at the Therapy on the Sopranos from a Jungian Lens

What if Tony Soprano had gone to a Jungian Analyst? The Sopranos is one of my favorite shows. In fact I often re-watch it while I write these blog posts and so I decided to write some blog posts on the show itself. I have said before that I think the shows enduring popularity is a result of its ability to show the macrocosm of a power structure and the microcosm of the individual psychologies that inhabit it. There is just one problem. Over the years I have drifted more post Jungian in my therapeutic orientation....

Mindfulness and Mental Health

How Present-Moment Awareness Can Transform Your Life Mindfulness, the practice of bringing non-judgmental awareness to the present moment, has emerged as a powerful tool for promoting mental health and well-being. Psychologists, therapists, and counselors are increasingly incorporating mindfulness-based interventions into their work with clients struggling with issues like anxiety, depression, trauma, ADHD, eating disorders, and more. The Benefits of Mindfulness Research has shown that regular mindfulness...

Understanding DARVO: Recognizing Abuse Tactics

Understanding DARVO: Recognizing Abuse Tactics in Relationships and Politics What does D.A.R.V.O. mean? DARVO is an acronym that stands for "Deny, Attack, and Reverse Victim and Offender." It refers to a common strategy employed by abusers and manipulators in which they flip the script by denying their abusive behavior, attacking the credibility and character of their victims, and positioning themselves as the true victim. By understanding the history and dynamics of DARVO, we can better recognize these toxic...

Experience the Healing Power of Brainspotting at Taproot Therapy in Vestavia Hills, Alabama

Taproot: Birmingham's Brainspotting Pioneers Are you struggling with complex PTSD, dissociative disorders, or treatment-resistant trauma? Brainspotting therapy at Taproot in Vestavia Hills, Alabama offers a powerful, brain-based path to healing. Our therapists are the most highly trained brainspotting practitioners in the Birmingham area, offering an integrative approach that combines brainspotting with parts work, somatic therapy, and experiential techniques for deep, transformative healing. At Taproot Therapy,...

Cognitive Distortions: Identifying and Challenging Negative Thinking Patterns

Executive Summary: The Science of Thinking Traps The Clinical Definition: Cognitive Distortions are not "crazy" thoughts; they are evolutionary mental shortcuts (heuristics) that have become maladaptive. They are the brain's attempt to predict the future based on fear rather than evidence. Key Mechanisms: The Negativity Bias: The human brain is wired to prioritize danger signals over safety signals (Amygdala activation). Confirmation Bias: Once a distortion forms (e.g., "I am unlovable"), the Reticular Activating...

Understanding Dyslexia: Challenges, Strengths, and Strategies for Success

Executive Summary: The Dyslexic Mind The Clinical Definition: Dyslexia is a neurobiological difference in the way the brain processes written language. It is characterized by difficulties with Phonological Processing (breaking words into sounds) and Rapid Automatized Naming. The Neurobiology: Inefficient Pathways: While neurotypical readers use the efficient "Visual Word Form Area" (back of the brain), dyslexic readers over-activate the Broca's Area (front of the brain), making reading a manual, energy-expensive...

Recognizing and Understanding Autism in Adulthood

Executive Summary: The Neurobiology of Adult Autism The Paradigm Shift: Autism is not a "behavioral disorder" to be fixed; it is a distinct neurotype characterized by Bottom-Up Processing. While neurotypical brains filter out details to see the "gist," autistic brains process raw sensory data first, leading to intensity, depth, and potential overwhelm. Key Clinical Concepts: Monotropism: The defining feature of autism is likely not "social deficits," but an "attention tunnel" style of focus. Autistic brains...

Understanding Demisexuality: Exploring the Gray Area Between Asexuality and Allosexuality

Executive Summary: The Mechanics of Demisexuality The Definition: Demisexuality is a sexual orientation on the asexual spectrum where an individual cannot experience sexual attraction until a strong emotional bond is formed. It is not a choice to abstain; it is a neurological precondition for desire. Key Concepts: Primary vs. Secondary Attraction: Demisexuals lack "Primary Attraction" (instant physical attraction based on looks) but experience "Secondary Attraction" (attraction based on personality and...

The Path to Recovery: An Overview of Addiction Treatment Options

What Type and Length of Addiction Treatment is Best? Addiction is a complex and chronic condition that requires professional treatment and ongoing support to achieve and maintain recovery. With the variety of treatment options available, it can be challenging to navigate the landscape of addiction care. This article provides an overview of the most common addiction treatment approaches, empowering individuals and families to make informed decisions about their path to recovery. Levels of Addiction Treatment...

Harnessing the Power of Positive Affirmations for Self-Improvement

How to make Positive Affirmations in Therapy? Positive affirmations are simple yet powerful statements that can help to reprogram our subconscious mind, challenge limiting beliefs, and promote self-growth and improvement. By regularly repeating affirmations that align with our goals and values, we can cultivate a more positive and empowering mindset and take proactive steps towards creating the life we desire. This article explores the science behind positive affirmations and provides guidance on how to...

Comprehensive Treatment Strategies for Major Depressive Disorder

How to get Help for Depression Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a serious mental health condition characterized by persistent feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and a loss of interest in activities. It can significantly impact an individual's daily functioning and quality of life. This article explores comprehensive treatment strategies for MDD, combining various approaches to achieve the best possible outcomes. Pharmacotherapy Antidepressants: Antidepressant medications, such as selective serotonin reuptake...

Navigating Treatment Options: The Most Effective Medications for Anxiety and Depression

How to get Medication for Anxiety? When it comes to treating anxiety and depression, medication can be an essential component of a comprehensive treatment plan. While therapy and lifestyle changes are also important, the right medication can help alleviate symptoms and improve overall functioning. This article explores some of the most effective medications for anxiety and depression. Medications for Anxiety Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs): SSRIs, such as fluoxetine (Prozac), sertraline (Zoloft),...

Recognizing the Signs: A Guide to Anxiety and Depression Symptoms

How to know if you have anxiety? Anxiety and depression are two of the most common mental health disorders, affecting millions of people worldwide. Recognizing the symptoms of these conditions is crucial for seeking timely treatment and support. This article provides an overview of the signs and symptoms associated with anxiety and depression. Anxiety Symptoms Excessive worry or fear Restlessness or feeling on edge Difficulty concentrating Irritability Sleep disturbances Physical symptoms (e.g., rapid heartbeat,...

An Introduction to Lifespan Integration Therapy

What is Lifespan Integration Therapy? Lifespan Integration (LI) is a gentle, body-based therapeutic method that aims to heal without re-traumatizing. Developed by Peggy Pace, a clinical psychologist, LI is founded on the understanding that the mind-body system is equipped with a natural ability to heal itself, given the right conditions and support. LI therapy works by helping clients to access and integrate unresolved traumatic memories and experiences that are believed to underlie many mental health issues....

Lifespan Integration Techniques and Protocols

The Basic Lifespan Integration Protocol The Basic Lifespan Integration Protocol is the foundational technique used in LI therapy. It involves guiding the client through their timeline, from birth to the present moment, while applying specific prompts and techniques to facilitate integration and healing. Book with a Lifespan Integration Therapist Here Other Articles on Lifespan Integration Part1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 The basic protocol typically follows these steps: Grounding and resourcing: The therapist guides...

Lifespan Integration for Specific Mental Health Concerns

Lifespan Integration for Anxiety and Panic Disorders Anxiety and panic disorders are characterized by chronic, debilitating feelings of fear, worry, and unease. These feelings are often rooted in early, unresolved experiences of threat, danger, or vulnerability. Lifespan Integration can be a powerful tool for resolving the underlying traumas and attachment wounds that fuel anxiety and panic. By processing these experiences and linking them to more adaptive, resourced states, LI can help to rewire the neural...

The Science Behind Lifespan Integration: Healing Through Neural Integration

The Role of Neural Networks in Lifespan Integration At the heart of Lifespan Integration therapy is the understanding that the brain is a complex, interconnected network of neural pathways and circuits. These neural networks are formed through our experiences, beginning in utero and continuing throughout our lifespan. When we experience trauma or adverse life events, especially in childhood, it can disrupt the normal integration of these neural networks. Traumatic experiences can become "stuck" or frozen in time,...

The Brain-Body Connection: How Somatic Experiencing Works

The Impact of Trauma on the Brain and Body Trauma can have a profound impact on both the brain and the body. When an individual experiences a traumatic event, the body's natural stress response is activated, releasing a flood of stress hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline. This response prepares the body for fight, flight, or freeze, enabling the individual to respond to the perceived threat. However, when the traumatic event is overwhelming or prolonged, the stress response can become dysregulated, leading...

Understanding Somatic Experiencing: A Mind-Body Approach to Healing Trauma

What is Somatic Experiencing? Somatic Experiencing (SE) is a body-oriented therapeutic approach developed by Dr. Peter Levine to address the effects of trauma. It is based on the understanding that trauma is not just a psychological phenomenon but also has a significant physiological impact on the body. SE focuses on the biological responses to trauma and aims to release traumatic shock, which is stored in the body, leading to the alleviation of trauma symptoms. The approach is grounded in the observation of...

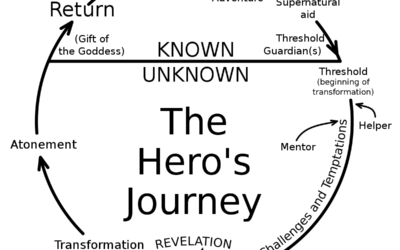

The 12 Archetypes: How They Shape Our Lives as Consumers, Voters, and Romantic Partners

Archetypes Across Culture and Advertising and Myth The concept of archetypes, as popularized by psychologist Carl Jung, has found its way into various aspects of our lives, from the way we consume products to how we vote and even how we navigate our romantic relationships. In her book "Awakening the Heroes Within," Carol Pearson introduces a model of 12 archetypes that have become widely recognized in popular culture. These archetypes are: The Innocent, The Lover, The Orphan, The Creator, The Hero, The Jester,...

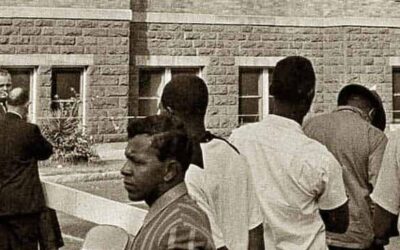

The Photography of Spider Martin: Capturing the Struggle for Civil Rights

The photograph was taken during the civil rights demonstrations of March 1965, sometime between Bloody Sunday and the Selma to Montgomery March. Alabama Media Group Who Was Spider Martin? In times of great societal upheaval and injustice, the power of visual storytelling can be a catalyst for change, awareness, and healing. The photographs of Spider Martin, particularly his documentation of the Civil Rights Movement and the Selma to Montgomery marches, stand as a testament to the transformative impact of...

African American Resilience and Creative Expression: Combating Generational Trauma and Reconnecting with Cultural Roots

The African American experience has been marked by a history of trauma, oppression, and displacement, resulting in a sense of rootlessness and disconnection from African myths and traditions. This phenomenon is not merely sociological but biological. Research into epigenetics suggests that the stress of trauma can modify gene expression, passing the physiological effects of oppression down through generations. However, in the face of these challenges, African Americans have demonstrated remarkable resilience and...

African American Folk Arts and Traditions: Resilience, Resistance, and Roots

African American Folk Arts as a Means to Heal Inter-Generational Trauma The African American experience in the United States is a testament to the capacity of the human spirit to transmute suffering into beauty. African American folk arts and traditions have played a vital role in shaping the cultural landscape of the United States, particularly in the Deep South. These practices—encompassing music, quilting, storytelling, ironworking, and culinary arts—have served as powerful means of expression,...

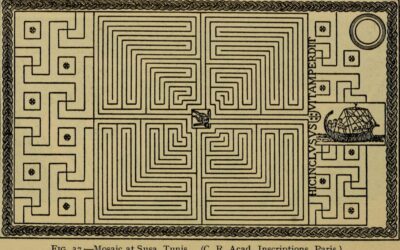

The Labyrinth in Jungian Psychology: Traversing the Winding Path of Individuation

What is a Labyrinth? "The labyrinth is an ancient symbol that relates to wholeness. It combines the imagery of the circle and the spiral into a meandering but purposeful path." - Dr. Sandra Wasko-Flood Read This Article as a Pdf: What is a Labyrinth Labyrinth Locator Find a Labyrinth Anywhere in the World Near You Main Points and Key Ideas: The labyrinth as an archetypal symbol in human culture and psychologyJungian interpretations of the labyrinth as a representation of the individuation processThe labyrinth's...

Maurice Merleau-Ponty: Embodied Perception and Existential Phenomenology

Maurice Merleau-Ponty: The Philosopher of the Body and the Flesh of the World Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961) stands as a pivotal figure in 20th-century thought, a French phenomenologist who dared to challenge the ancient dualism separating the mind from the body. While his contemporary Jean-Paul Sartre focused on radical freedom and consciousness, Merleau-Ponty focused on the Body—not as a biological machine, but as the very ground of our existence. His work bridges the gap between the abstract world of...

Ernst Cassirer: Philosopher of Symbolic Forms and Cultural Theory

Who was Ernst Cassirer? Ernst Cassirer (1874-1945) was a German-Jewish philosopher who made significant contributions to the fields of epistemology, philosophy of science, intellectual history, and cultural theory. His work on symbolic forms and his neo-Kantian approach to understanding human culture and cognition have had a lasting impact on various disciplines, including philosophy, anthropology, linguistics, and cognitive science. Cassirer's theories have influenced subsequent thinkers and continue to be...

The Ultimate Guide to Starting a Successful Private Practice as a Therapist

The Illusion of Progress: How Psychotherapy Lost Its Way

Key Points: Psychotherapy is facing an identity and purpose crisis in the era of market-driven healthcare, as depth, nuance, and the therapeutic relationship are being displaced by cost containment, standardization, and mass-reproducibility. This crisis stems from a shift in notions of the self and therapy's aims, shaped by the rise of neoliberal capitalism and consumerism. The "empty self" plagued by inner lack pursues fulfillment through goods, experiences, and attainments. Mainstream psychotherapy largely...

The Villain Within: Applying Jungian Psychology for Fiction and Screenwriting Part 1

part 1: https://gettherapybirmingham.com/the-villain-with…nd-screenwriting/ part 2: https://gettherapybirmingham.com/using-jungian-ps…d-fiction-part-2/ part 3: https://gettherapybirmingham.com/applying-jungian…onality-theories/ Read More on Jung here: Carl Jung's Major Influences Jungian Analysis Archetypes Jung’s Method Jungian Thought How do you Write a Villain? In the realm of storytelling, villains serve as the embodiment of the hero's greatest challenges and fears. They are the immovable force that the...

⛵Carolyn Robistow on Gray Area Drinking and Brainspotting for Harm Reduction and Addiction

In this episode, Joel Blackstock interviews Carolyn Robistow, a life coach and brain spotting practitioner who works with clients from her boat. Carolyn talks about keeping a captain's log, dealing with potential pirate threats, and her involvement in the America's Great Loop Cruisers group for boaters. She describes her approach of using a "trifecta of change" with three pillars: 1) A personalized daily support plan based on the client's values, 2) Brain spotting and other somatic techniques to make subcortical...

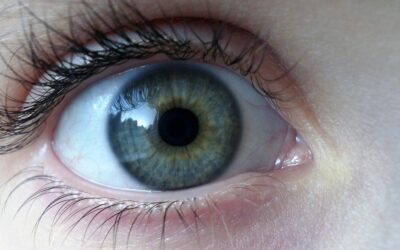

Attention Pupils! Windows to the Soul; Extensions of the Brain

How Therapists can Use the Pupil to Heal Trauma One of the reasons that I left EMDR and started to pursue brainspotting as the primary brain based medicine that I use as a provider was because of pupil dilation. Years ago when I was just starting out as a therapist I noticed that pupil dilation patterns were a good indicator of how well a patient was processing trauma. I would use a patient's pupil dilation and movement to see how well EMDR was working. During EMDR patients don’t talk much until the end of...

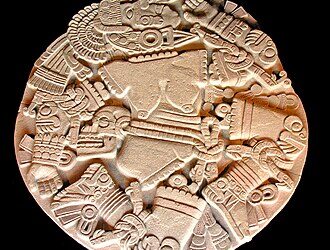

Book Review of of Aztec Philosophy by James Maffie

The Collision of Ontologies: When Monism Met Dualism The historical collision that occurred when Hernán Cortés arrived in Tenochtitlán in 1519 was not merely a military conquest; it was a catastrophic clash of incompatible metaphysical realities. To the Spanish Catholic mind, the universe was dualistic: God vs. Creation, Good vs. Evil, Spirit vs. Matter. When they encountered the Aztecs, they projected this framework onto them, seeing "idols" and "devils." However, as contemporary philosopher James Maffie argues...

Getting stuck in therapy as a provider or a patient? Here are 80 different therapy interventions to try!

The Therapist’s Grand Grimoire: A Comprehensive Narrative Encyclopedia of 80 Clinical Interventions The practice of psychotherapy is not a monolith but a mosaic composed of hundreds of distinct techniques developed over a century of clinical experimentation and research. For the modern clinician, the challenge is not merely to learn these interventions but to integrate them into a cohesive framework that addresses the cognitive, somatic, and existential dimensions of the human experience. This comprehensive guide...

How Therapists Can Recognize the onset of Schizophrenia in the Clinic

How to Recognize Schizophrenia Schizophrenia is a complex mental health disorder that significantly impacts an individual's thoughts, emotions, and behavior. By gaining a comprehensive understanding of the condition and implementing effective strategies, mental health professionals can provide better support and improve the quality of life for individuals living with schizophrenia. Early Signs and Diagnosis Recognizing the early signs of schizophrenia is crucial for prompt intervention. Common indicators include:...

5 Common Myths About Therapy Debunked

5 Common Therapy Myths Debunked: Why Seeking Help Matters Understanding the Barriers to Mental Health Treatment In today's fast-paced world, prioritizing mental health is crucial. Yet, many individuals hesitate to seek therapy due to persistent misconceptions. This article aims to debunk these myths and provide valuable insights to help you make an informed decision about seeking therapy. Key Takeaways: Therapy is more affordable than you might think The therapy experience differs from movie portrayals Everyone...

Interview with Psychotherapist Win Schepps on Why Children Need to Know it’s Ok to Cry

Interview with Winston Schepps 🌟📚 Meet Win Scheppes: A Lifelong Friend, Mentor, and Dedicated Social Worker in Birmingham Alabama at 86! 🤝💼 Discover the inspiring story of Win Scheppes, a remarkable social worker who continues to make a difference in people's lives well into his 86th year. With unwavering passion, he exclaims, "I love doing therapy so damn much," showcasing his unrelenting commitment to his profession. For an incredible 57 years, he has served his community from his Homewood office,...

David Tacey Interview on Carl Jung, Mysticism, Comparative Religion and the Politics of Mythology

Exploring the Depths of Jungian Psychology: An Interview with David Tacey Buy Tacey's Books on Amazon! God's and Diseases The Jung Reader The Post Secular Sacred The Darkening Spirit How to Read Jung Jung and Spirituality Religion as Metaphor Jung and The New Age The Spirituality Revoloution Remaking Men The Edger of the Sacred Re: Enchantmernt In a fascinating interview with Joel Blackstock from the Taproot Therapy Collective podcast, David Tacey, a renowned Australian public intellectual, writer, and...

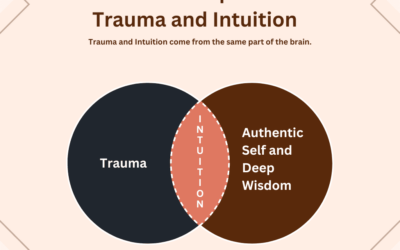

The Relationship between Intuition and Trauma

The Relationship between Intuition and Trauma Did you enjoy this article? Checkout the podcast here: https://gettherapybirmingham.podbean.com/ Many artists that have spoken to describe their process as "tuning into a radio wave". One artist told me that she did not even know what she was making until it is all done. Many effective creatives explain that it does not feel like they create art. Instead it feels like their art is simply coming through them. Joseph Campbell used to say that the artist swims in...

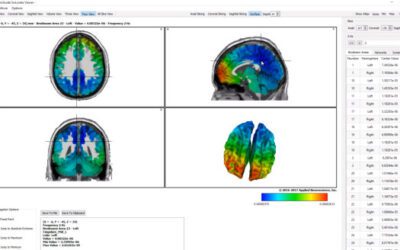

What is the Difference in QEEG Brain Mapping, Trans Cranial Magnetic Stimulation (TCMS), Neurofeedback (MCNF), Neurostimulation, and Biofeedback?

Decoding Neuromodulation: QEEG, Neurofeedback, and Neurostimulation Explained The world of **neuromodulation**—therapies that use technology to change nervous system activity—can be confusing. You may wonder how these advanced modalities differ, what their history is, and how they can potentially help you achieve better mental health and cognitive function. Did you enjoy this article? Check out the podcast here: https://gettherapybirmingham.podbean.com/ Quantitative Electroencephalogram (qEEG) Brain Mapping: The...

Peak Neuroscience is now offering neurostimulation and q-EEG brain mapping at Taproot Therapy!

We are excited to announce we will be offering qEEG Brain Mapping and Neurostimulation with Peak Neuroccience! You can register for a special rate on the first 10 sessions if get on the waitlist before they open. You can read more about brain mapping and q-EEG below. Did you enjoy this article? Checkout the podcast here: https://gettherapybirmingham.podbean.com/ Unlocking Your Brain's Potential with Quantitative EEG (QEEG) Brain Mapping Quantitative EEG (QEEG) brain mapping is a cutting-edge technique that...

The Body Keeps the Score 2? ; The Path Forward for Trauma Treatment

What if Bessel van der Kolk wrote a sequel to his influential book on trauma today? Did you enjoy this article? Checkout the podcast here: https://gettherapybirmingham.podbean.com/ e If anyone is familiar with the book The Body Keeps the Score, by world renowned physician Bessel van der Kolk, the title of this article is obvious hyperbole. I have no idea if he would or what Bessel van der Kolk would write as a sequel to The Body Keeps the Score. I am sure his publishers have offered him an enormous cash advance...

Karen Horney

Who was the female psychoanalyst and what do her theories say about trauma and personality? Did you enjoy this article? Checkout the podcast here: https://gettherapybirmingham.podbean.com/ Karen Horney was a German psychoanalyst. Her career came into prominence in the nineteen twenties when she formed theories on human attachment and neurosis that split from Freud’s key ideas. Horney’s theory of personality development and individuation are still highly relevant to modern theories of personality, attachment...

How do I become a therapist?

How much does it cost to become a therapist? How do I become a therapist? Becoming a Mental Health Practitioner in Alabama: Requirements, Costs, and Pathways Key Points and Summary: This is the most common question that we get. Don't worry we have an answer for you! What is the difference in a psychotherapist and a psychiatrist? What are the different types of therapists? Psychiatrists and Nurse Practitioners can prescribe medication. A psychiatrist is a licensed medical doctor. They are licensed by the AMA. They...

Karen Horney Article 4/4

Karen Horney Moving Away From People Karen Horney was a German psychoanalyst. Her career came into prominence in the nineteen twenties when she formed theories on human attachment and neurosis that split from Freud’s key ideas. Horney’s theory of personality development and individuation are still highly relevant to modern theories of personality, attachment psychology and psychological trauma. Horney observed that children deploy three different coping styles during the time they are individuating from the...

Karen Horney Part 3/4

Karen Horney Moving Against People Karen Horney was a German psychoanalyst. Her career came into prominence in the nineteen twenties when she formed theories on human attachment and neurosis that split from Freud’s key ideas. Horney’s theory of personality development and individuation are still highly relevant to modern theories of personality, attachment psychology and psychological trauma. This third part of a four part article will explore the moving against people personality style. In Horney’s theory of...

Karen Horney Part 2/4

Karen Horney Part 2/4 Moving Towards People Karen Horney was a German psychoanalyst. Her career came into prominence in the nineteen twenties when she formed theories on human attachment and neurosis that split from Freud’s key ideas. Horney’s theory of personality development and individuation are still highly relevant to modern theories of personality, attachment psychology and psychological trauma. Horney observed that children deploy three different coping styles during the time they are individuating from...

Karen Horney Part 1/4

Karen Horney Who was Karen Horney? Karen Horney was a German psychoanalyst. Her career came into prominence in the nineteen twenties when she formed theories on human attachment and neurosis that split from Freud’s key ideas. Horney’s theory of personality development and individuation are still highly relevant to modern theories of personality, attachment psychology and psychological trauma. Even though she is not well remembered, her work is as relevant as it was at the turn of the century. Applying her...

Everything you ever wanted to know about Brainspotting

Everything You Ever Wanted to Know about Brainspotting: A Clinical Deep Dive Trauma activates our body’s fight or flight system making us experience strong emotional and physical reactions without a logical cause which can make you feel angry or scared before you can intellectually understand why you react that way because reexperiencing trauma is not a choice but an unconscious reaction. Brainspotting is a revolutionary new trauma processing tool to help you process this unconscious reaction because to heal...

New Podcast Episode: Brainspotting Changed my Life

Yellow garden spiders have a fat yellow abdomen slicked with yellow and black stripes. They weave a tiny white squiggle in the center of their webs. I stare at the faintly milky zig zag as it sways when wind moves the web and stirs the iris sepals it hangs between in my mothers garden. I am biting on the seam of injection molded red plastic in a 1980s baby walker. I ponder the way that Alabama red clay cakes in the grooves of my tennis shoe and poke it with a stubby finger and later a small twig. My dreams...

How Do You Brainspot Patients with Severe Dissociation?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9GkEckbtKAY Brainspotting Techniques for Severe Dissociation in Trauma Therapy Brainspotting is a powerful technique for treating severe trauma and PTSD. However, when working with patients experiencing severe dissociation, therapists may face unique challenges. This article explores effective strategies for applying Brainspotting to clients with severe dissociation, enhancing trauma therapy outcomes. Learn more about the basics of Brainspotting Understanding the Challenge Severe...

Brainspotting Changed My Life. Can It Change Yours?

Yellow garden spiders have a fat yellow abdomen slicked with yellow and black stripes. They weave a tiny white squiggle in the center of their webs. I stare at the faintly milky zig zag as it sways when wind moves the web and stirs the iris sepals it hangs between in my mothers garden. I am biting on the seam of injection molded red plastic in a 1980s baby walker. I ponder the way that Alabama red clay cakes in the grooves of my tennis shoe and poke it with a stubby finger and later a small twig. My dreams were a...

The Most Common Images in Dreams and What They Mean

Dreams are so commonly associated with therapy because dreams are such a purely projective experience. In a way dreams are our own personal mythology. Many times a patient will bring a recurring dream to therapy that has occurred for many years. Recurring dreams are attempts that your subconscious is making to “tell” you something. If you are not listening the dream will continue to recur, sometimes for years. Sometimes it takes me and a patient a while to chew on what the meaning of this recurring dream is, but...