Unveiling the Complexities of Dissociation: Theories, Brain Processes, Types, and Treatment Options

Dissociation is a perplexing and often misunderstood mental phenomenon that has captured the attention of researchers, clinicians, and the general public alike. It is characterized by a profound sense of disconnection between one’s thoughts, emotions, memories, and sense of self. Dissociation exists on a spectrum, ranging from mild and transient experiences, such as daydreaming, to severe and persistent conditions, such as dissociative disorders. In this comprehensive article, we will explore the intricacies of dissociation, delving into the major theories that attempt to explain its nature, the neurobiological processes that underlie it, the different types of dissociation, how it feels to those who experience it, its possible evolutionary purpose, and the most effective treatment options available.

Key Ideas:

- Dissociation is a mental phenomenon characterized by a sense of disconnection between one’s thoughts, emotions, memories, and sense of self, existing on a spectrum from mild to severe experiences.

- The Structural Dissociation Theory suggests that dissociation arises from a lack of integration between different parts of the personality, often resulting from severe trauma.

- The Dissociative Taxon Theory proposes that dissociation is a distinct mental state characterized by specific symptoms and associated with biological and psychological vulnerabilities.

- The Sociocognitive Theory argues that dissociative experiences are shaped by an individual’s beliefs, expectations, and social context, rather than being a distinct mental state or biological predisposition.

- Neuroimaging studies have revealed altered brain activity in the prefrontal cortex, limbic system, insula, and default mode network during dissociative experiences.

- The main types of dissociation include depersonalization, derealization, amnesia, and identity confusion and alteration.

- The experience of dissociation can be perplexing and distressing, leading to feelings of disconnection, unreality, and memory gaps, with varying severity and impact on daily life.

- Dissociation may have evolved as a protective mechanism to help individuals cope with overwhelming stress or trauma, but can become maladaptive when it persists beyond the initial traumatic event.

- Treatment options for dissociation include Lifespan Integration (LI), Somatic Experiencing (SE), Brainspotting (BSP), and Emotional Transformation Therapy (ETT).

- QEEG brain mapping and neuromodulation techniques, such as neurofeedback and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), offer promising avenues for assessing and treating dissociative disorders by targeting specific patterns of brain activity.

- General principles for treating dissociative disorders include establishing safety and stability, building a strong therapeutic alliance, working at the client’s pace, addressing co-occurring conditions, and fostering resilience and empowerment.

Theories of Dissociation

Structural Dissociation Theory

The Structural Dissociation Theory, proposed by van der Hart, Nijenhuis, and Steele (2006), posits that dissociation arises from a lack of integration between different parts of the personality. According to this theory, when an individual experiences severe trauma, their personality may split into two or more distinct parts, each with its own sense of self, emotions, and behaviors. These parts are often referred to as the “apparently normal part” (ANP) and the “emotional part” (EP). The ANP is responsible for carrying out daily functions and presenting a façade of normalcy to the outside world, while the EP holds the traumatic memories and associated emotions. The lack of integration between these parts results in the dissociative symptoms observed in individuals with trauma-related disorders.

Dissociative Taxon Theory

The Dissociative Taxon Theory, introduced by Waller, Putnam, and Carlson (1996), suggests that dissociation is a distinct mental state characterized by a specific set of symptoms, such as depersonalization, derealization, and amnesia. This theory proposes that individuals with dissociative disorders have a distinct “taxon” or subgroup of dissociative experiences that are qualitatively different from normal experiences. The taxon is believed to be a discrete category, rather than a continuum, and is thought to be associated with specific biological and psychological vulnerabilities. This theory has been influential in the development of diagnostic criteria for dissociative disorders.

Sociocognitive Theory

The Sociocognitive Theory, advanced by Spanos (1994), offers a contrasting perspective on dissociation. This theory suggests that dissociative experiences are not the result of a distinct mental state or biological predisposition, but rather are shaped by an individual’s beliefs, expectations, and social context. According to this view, dissociative experiences are learned behaviors that are reinforced by social and cultural factors, such as media portrayals of dissociation, societal expectations, and the influence of therapists or authority figures. The Sociocognitive Theory challenges the notion of dissociation as a pathological condition and instead emphasizes the role of social and cognitive processes in shaping these experiences.

Brain Processes in Dissociation

Recent advances in neuroimaging and neuroscience have shed light on the complex brain processes that underlie dissociation. Studies have consistently shown altered activity in several key brain regions and networks during dissociative experiences. One of the most prominent findings is the altered function of the prefrontal cortex, a region involved in executive functions, such as attention, decision-making, and emotional regulation (Lanius et al., 2010). In individuals with dissociative disorders, the prefrontal cortex exhibits reduced activation and connectivity, suggesting a diminished ability to integrate and regulate cognitive and emotional processes.

Another important brain region implicated in dissociation is the limbic system, which is responsible for processing emotions and memories. Research has demonstrated a disruption in the integration between the prefrontal cortex and the limbic system during dissociative states (Sierra & Berrios, 1998). This disconnection may contribute to the sense of detachment from one’s emotions and memories that is characteristic of dissociation. Additionally, studies have found altered activity in the insula, a region involved in body awareness and interoception, which may underlie the feelings of depersonalization and derealization often reported by individuals with dissociative disorders (Simeon et al., 2000).

Furthermore, neuroimaging studies have revealed abnormalities in the default mode network (DMN), a set of brain regions that are active when an individual is not focused on a specific task (Daniels et al., 2016). The DMN is thought to be involved in self-referential processing, autobiographical memory, and mind-wandering. In individuals with dissociative disorders, the DMN exhibits altered connectivity and activation patterns, which may contribute to the fragmentation of self-experience and the difficulty in integrating personal memories.

While these neurobiological findings provide valuable insights into the brain processes underlying dissociation, it is important to note that the relationship between brain function and dissociative experiences is complex and multifaceted. Dissociation likely arises from a combination of biological, psychological, and social factors, and further research is needed to fully understand the intricate interplay between these elements.

Types of Dissociation

Depersonalization

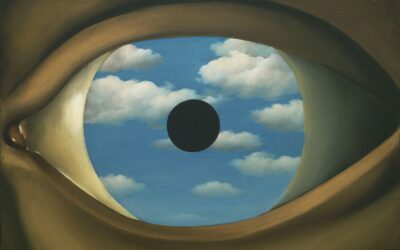

Depersonalization is a type of dissociation that involves a pervasive sense of detachment from one’s own thoughts, feelings, and actions (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Individuals experiencing depersonalization often describe feeling like an outside observer of their own mental processes or body. They may feel as though they are in a dream-like state or that their body is not their own. Depersonalization can be a highly distressing experience, as it challenges one’s fundamental sense of self and reality. It is important to note that depersonalization can occur in a variety of contexts, including both normal and pathological states. Transient episodes of depersonalization are relatively common in the general population, often occurring in response to stress, fatigue, or drug use. However, when depersonalization becomes chronic and causes significant distress or impairment in daily functioning, it may be indicative of a dissociative disorder.

Derealization

Derealization is another type of dissociation that involves a sense of detachment from one’s surroundings (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Individuals experiencing derealization may perceive the world around them as unreal, dreamlike, or distorted. They may feel as though they are in a fog or that their environment lacks depth and emotional connection. Derealization can be a highly unsettling experience, as it alters one’s perception of reality and can lead to a sense of isolation and disconnection from others. Like depersonalization, derealization can occur in both normal and pathological contexts. Brief episodes of derealization are not uncommon, particularly in response to stress or trauma. However, when derealization becomes persistent and interferes with daily life, it may be a sign of a more serious dissociative disorder.

Amnesia

Dissociative amnesia is characterized by the inability to recall important personal information, typically of a traumatic or stressful nature (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). This type of amnesia is distinct from normal forgetting and cannot be attributed to other medical conditions or substances. Individuals with dissociative amnesia may experience gaps in their memory that range from a few minutes to several years. In some cases, the amnesia may be limited to specific aspects of an event, while in others, it may encompass entire periods of one’s life. Dissociative amnesia is thought to serve a protective function, allowing the individual to cope with overwhelming stress or trauma by disconnecting from the associated memories. However, when the amnesia persists and interferes with daily functioning, it can be highly distressing and may require professional intervention.

Identity Confusion and Alteration

Dissociative identity confusion and alteration are two related types of dissociation that involve disturbances in one’s sense of self. Identity confusion is characterized by a profound sense of uncertainty about one’s identity, while identity alteration involves the presence of two or more distinct personality states (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). These states may have their own unique patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving, and may even have different names, ages, genders, or other characteristics. Individuals with identity alteration may experience a sense of possession or loss of control over their actions, as well as gaps in memory between the different personality states. These experiences can be highly distressing and can lead to significant impairment in social, occupational, and other important areas of functioning. Dissociative identity confusion and alteration are often associated with severe and prolonged trauma, particularly in childhood, and may represent an extreme form of coping with overwhelming stress.

The Experience of Dissociation

For individuals who experience dissociation, the phenomenon can be both perplexing and distressing. Many describe feeling disconnected from their own thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations, as though they are observing themselves from outside their own body. This sense of detachment can be accompanied by feelings of unreality or distortion in one’s perception of the world around them. Some individuals may feel as though they are in a dream-like state, or that time is passing in a strange, disjointed manner. Dissociation can also involve gaps in memory, where individuals may be unable to recall important personal information or events.

It is important to recognize that the experience of dissociation can vary widely from person to person. Some may have only fleeting moments of dissociation, while others may experience chronic and severe symptoms that significantly impact their daily lives. Additionally, some individuals may not initially recognize that they are experiencing dissociation, as it can become a habitual way of coping with stress or trauma. They may attribute their experiences to other factors, such as fatigue, stress, or normal forgetfulness.

For those who do recognize their dissociative experiences, the impact can be significant. Dissociation can lead to a profound sense of isolation and disconnection from others, as well as feelings of shame, confusion, and self-doubt. It can interfere with an individual’s ability to form and maintain healthy relationships, as well as their capacity to function in work, school, and other important areas of life. Moreover, dissociation can be a barrier to effective treatment, as it may make it difficult for individuals to engage in therapy and process traumatic experiences.

Given the complex and varied nature of dissociation, it is essential for mental health professionals to approach the phenomenon with sensitivity, empathy, and a thorough understanding of its potential causes and consequences. By creating a safe and supportive therapeutic environment, clinicians can help individuals with dissociative experiences to better understand and cope with their symptoms, and ultimately to work towards healing and recovery.

Evolutionary Purpose of Dissociation

While dissociation can be a source of significant distress and impairment, it is important to consider its potential evolutionary purpose. Many researchers believe that dissociation evolved as a protective mechanism to help individuals cope with overwhelming stress or trauma (Putnam, 1997). By disconnecting from the emotional impact of a traumatic event, dissociation may allow an individual to continue functioning in the face of adversity. This may have been particularly adaptive in situations where physical escape was not possible, such as in cases of childhood abuse or neglect.

From an evolutionary perspective, dissociation can be seen as a type of “flight” response, allowing an individual to mentally escape a threatening situation when physical escape is not possible. By detaching from the emotional and physical sensations associated with the trauma, the individual may be able to preserve some sense of psychological integrity and continue to function in other areas of life. In this sense, dissociation can be viewed as a creative and adaptive response to overwhelming stress, rather than simply a pathological condition.

However, it is important to recognize that while dissociation may serve a protective function in the short term, it can become maladaptive when it persists beyond the initial traumatic event. When dissociation becomes a habitual response to stress or a chronic way of coping with the world, it can lead to significant difficulties in daily life and the development of dissociative disorders. In these cases, the evolutionary purpose of dissociation may be overshadowed by its negative impact on an individual’s overall functioning and well-being.

Understanding the evolutionary context of dissociation can help to destigmatize the experience and provide a more compassionate and nuanced perspective on the phenomenon. Rather than viewing dissociation as a sign of weakness or pathology, it can be seen as a natural, albeit sometimes maladaptive, response to overwhelming stress. This perspective can help to validate the experiences of those who struggle with dissociation and provide a foundation for more effective and empathetic treatment approaches.

Treatment Options for Dissociation

Lifespan Integration (LI)

Lifespan Integration (LI) is a gentle, body-based therapy that aims to help clients reconnect with their past experiences and integrate them into their present reality (Pace, 2012). LI is based on the premise that traumatic memories are often stored in a fragmented, disconnected manner, leading to dissociative symptoms and a disrupted sense of self. By reprocessing these traumatic memories and integrating them into a coherent life narrative, LI seeks to reduce dissociative symptoms and promote a more unified sense of self.

In LI therapy, the therapist guides the client through a timeline of their life experiences, focusing on both positive and negative events. The client is encouraged to focus on bodily sensations and emotions as they revisit each memory, while the therapist provides a safe and supportive presence. Through this process, the client can begin to develop a more coherent and integrated sense of their life story, reducing the need for dissociative defenses.

LI is a relatively new therapy, but initial research has shown promising results in the treatment of dissociative disorders and other trauma-related conditions (Pace, 2012). One of the strengths of LI is its gentle, non-invasive approach, which can be particularly beneficial for clients who may be wary of more intense or confrontational therapies. Additionally, LI’s focus on the body and emotions may help clients to develop a greater sense of self-awareness and emotional regulation, which are essential skills for coping with dissociative symptoms.

Somatic Experiencing (SE)

Somatic Experiencing (SE) is another body-oriented therapy that has shown promise in the treatment of dissociative disorders (Levine, 2010). SE is based on the idea that trauma is stored in the body and that by learning to regulate and release these stored traumatic experiences, individuals can reduce dissociative symptoms and improve overall functioning.

In SE therapy, the therapist works with the client to develop an increased awareness of their bodily sensations and to learn to regulate their nervous system. This is done through a process of titration, in which the client is gradually exposed to small amounts of traumatic material while learning to maintain a state of calm and relaxation. Over time, the client can begin to process and release stored traumatic experiences, leading to a reduction in dissociative symptoms.

One of the key strengths of SE is its focus on the physiological aspects of trauma and dissociation. By helping clients to develop a greater sense of body awareness and to learn to regulate their nervous system, SE can provide a foundation for more effective trauma processing and integration. Additionally, SE’s emphasis on titration and gradual exposure can be particularly beneficial for clients who may be easily overwhelmed by traumatic material.

Brainspotting (BSP)

Brainspotting (BSP) is a relatively new therapy that has shown promise in the treatment of dissociative disorders (Grand, 2013). BSP is based on the idea that there are specific eye positions that correspond to stored traumatic experiences in the brain. By identifying and focusing on these “brainspots,” individuals can access and process traumatic material more effectively.

In BSP therapy, the therapist works with the client to identify specific eye positions that elicit a strong emotional response or physical sensation. The client is then encouraged to focus on this brainspot while the therapist provides bilateral stimulation, typically in the form of eye movements or sound. Through this process, the client can begin to access and process stored traumatic experiences, leading to a reduction in dissociative symptoms.

One of the unique aspects of BSP is its use of eye positions to access traumatic material. This approach is based on the idea that the brain stores traumatic experiences in a specific way and that by targeting these storage points, individuals can more effectively process and integrate these experiences. Additionally, BSP’s use of bilateral stimulation may help to facilitate the processing of traumatic material by engaging both hemispheres of the brain.

Emotional Transformation Therapy (ETT)

Emotional Transformation Therapy (ETT) is an integrative approach that combines elements of cognitive-behavioral therapy, neuroscience, and attachment theory to treat dissociative disorders (Thomas & Hatch, 2017). ETT is based on the idea that dissociation arises from a disruption in the normal process of emotional development and that by helping clients to identify and transform negative emotional patterns, dissociative symptoms can be reduced.

In ETT therapy, the therapist works with the client to identify core emotional schemas, which are patterns of emotional responding that have been shaped by early experiences and relationships. These schemas often involve negative beliefs about oneself, others, and the world, and can contribute to the development of dissociative symptoms. Through a process of experiential exercises, cognitive restructuring, and emotional processing, the client can begin to transform these negative schemas and develop more adaptive emotional responses.

One of the strengths of ETT is its integrative approach, which draws on multiple theoretical perspectives to provide a comprehensive treatment for dissociative disorders. By addressing both the cognitive and emotional aspects of dissociation, ETT can help clients to develop a greater sense of self-awareness, emotional regulation, and interpersonal effectiveness. Additionally, ETT’s focus on attachment and early emotional experiences may be particularly beneficial for clients with a history of childhood trauma or neglect.

Dissociation is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon that can have a significant impact on an individual’s mental health and overall well-being. By understanding the various theories, brain processes, types, and experiences of dissociation, as well as its potential evolutionary purpose, mental health professionals can provide more effective and empathetic treatment to those who struggle with this condition.

QEEG Brain Mapping and Neuromodulation

In recent years, there has been growing interest in the use of quantitative electroencephalography (QEEG) brain mapping and neuromodulation techniques in the assessment and treatment of dissociative disorders. These approaches offer a promising avenue for understanding the neurobiological underpinnings of dissociation and developing targeted interventions to address the specific brain patterns associated with this condition.

QEEG Brain Mapping

QEEG brain mapping is a non-invasive technique that uses electroencephalography (EEG) to measure and analyze the electrical activity of the brain. By placing electrodes on the scalp, QEEG can provide a detailed map of brain function, showing areas of over- or under-activation, as well as patterns of connectivity between different brain regions.

In the context of dissociative disorders, QEEG brain mapping has been used to identify specific patterns of brain activity that may underlie dissociative symptoms. For example, studies have found that individuals with dissociative disorders may exhibit increased theta wave activity in the frontal lobes, which is associated with a disconnection between cognitive and emotional processing (Lanius et al., 2006). Other studies have found altered patterns of connectivity between the prefrontal cortex and limbic system, which may contribute to the emotional dysregulation and memory disturbances often seen in dissociative disorders (Daniels et al., 2016).

By providing a detailed picture of brain function, QEEG brain mapping can help clinicians to develop a more targeted and individualized approach to treatment. For example, if a client exhibits specific patterns of brain activity associated with dissociation, the therapist may use this information to guide the selection of specific interventions, such as neurofeedback or transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), which can help to normalize brain function and reduce dissociative symptoms.

Neuromodulation Techniques

Neuromodulation techniques are a group of interventions that use various forms of energy, such as electricity or magnetic fields, to modulate brain activity and function. These techniques have shown promise in the treatment of a range of mental health conditions, including depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and are now being explored as a potential treatment for dissociative disorders.

One of the most widely studied neuromodulation techniques is neurofeedback, which uses real-time feedback of brain activity to help individuals learn to regulate their own brain function. In the context of dissociative disorders, neurofeedback has been used to target specific patterns of brain activity associated with dissociation, such as increased theta wave activity in the frontal lobes (Manchester et al., 1998). By learning to reduce this activity and increase more adaptive patterns of brain function, individuals with dissociative disorders may be able to reduce their symptoms and improve their overall functioning.

Another promising neuromodulation technique is transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), which uses a magnetic field to stimulate specific areas of the brain. TMS has been used to treat a range of mental health conditions, including depression and PTSD, and is now being explored as a potential treatment for dissociative disorders. In particular, TMS has been used to target the prefrontal cortex, which is thought to play a key role in the regulation of emotion and memory (Sar et al., 2014). By modulating activity in this region, TMS may help to reduce dissociative symptoms and improve overall functioning.

While the use of QEEG brain mapping and neuromodulation techniques in the treatment of dissociative disorders is still in its early stages, these approaches offer a promising avenue for future research and clinical practice. By providing a more detailed understanding of the neurobiological underpinnings of dissociation and offering targeted interventions to address specific patterns of brain function, these techniques may help to improve outcomes for individuals with dissociative disorders and provide new hope for healing and recovery.

However, it is important to note that these techniques should not be seen as a replacement for traditional psychotherapy and should be used in conjunction with a comprehensive treatment plan that addresses the individual’s unique needs and experiences. Additionally, as with any new treatment approach, more research is needed to fully understand the potential benefits and limitations of QEEG brain mapping and neuromodulation techniques in the treatment of dissociative disorders.

In conclusion, QEEG brain mapping and neuromodulation techniques represent an exciting new frontier in the assessment and treatment of dissociative disorders. By providing a more detailed understanding of the neurobiological basis of dissociation and offering targeted interventions to address specific patterns of brain function, these approaches may help to improve outcomes for individuals with dissociative disorders and provide new hope for healing and recovery. As research in this area continues to evolve, it will be important for mental health professionals to stay informed about the latest developments and to consider how these techniques may be integrated into their clinical practice to provide the most effective and comprehensive care for their clients.

In addition to the specific treatment approaches discussed in this article, there are several general principles that can guide the treatment of dissociative disorders.

These include:

1. Establishing safety and stability: Before beginning any trauma-focused work, it is essential to establish a sense of safety and stability in the client’s life. This may involve developing coping skills, creating a support system, and addressing any immediate safety concerns.

2. Building a strong therapeutic alliance: The relationship between the therapist and client is a crucial factor in the success of treatment. Therapists should strive to create a warm, empathetic, and collaborative relationship with their clients, while also maintaining appropriate boundaries and professional standards.

3. Working at the client’s pace: The treatment of dissociative disorders should be paced according to the individual needs and capacities of the client. Pushing too quickly into trauma-focused work can be counterproductive and may even re-traumatize the client.

4. Addressing co-occurring conditions: Dissociative disorders often co-occur with other mental health conditions, such as depression, anxiety, and substance abuse. It is important to assess and treat these conditions concurrently, as they can have a significant impact on the client’s overall functioning and well-being.

5. Fostering resilience and empowerment: Ultimately, the goal of treatment is not just to reduce symptoms, but to help clients develop a sense of resilience, empowerment, and hope for the future. This may involve building on the client’s strengths, developing new coping skills, and creating a sense of meaning and purpose in life.

References:

Daniels, J. K., Frewen, P., McKinnon, M. C., & Lanius, R. A. (2011). Default mode alterations in posttraumatic stress disorder related to early-life trauma: a developmental perspective. Journal of psychiatry & neuroscience: JPN, 36(1), 56-59.

Lanius, R. A., Bluhm, R., Lanius, U., & Pain, C. (2006). A review of neuroimaging studies in PTSD: heterogeneity of response to symptom provocation. Journal of psychiatric research, 40(8), 709-729.

Manchester, C., Allen, T., & Tachiki, K. H. (1998). Treatment of dissociative identity disorder with neurotherapy and group self-exploration. Journal of Neurotherapy, 2(4), 40-53.

Sar, V., Krüger, C., Martinez-Taboas, A., Middleton, W., & Dorahy, M. (2014). Sociocognitive and posttraumatic models of dissociation. In Dissociation and the dissociative disorders (pp. 81-98). Routledge.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

Grand, D. (2013). Brainspotting: The revolutionary new therapy for rapid and effective change. Sounds True.

Lanius, R. A., Vermetten, E., Loewenstein, R. J., Brand, B., Schmahl, C., Bremner, J. D., & Spiegel, D. (2010). Emotion modulation in PTSD: Clinical and neurobiological evidence for a dissociative subtype. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(6), 640-647.

Levine, P. A. (2010). In an unspoken voice: How the body releases trauma and restores goodness. North Atlantic Books.

Pace, P. (2012). Lifespan Integration: Connecting ego states through time. Lifespan Integration, LLC.

Putnam, F. W. (1997). Dissociation in children and adolescents: A developmental perspective. Guilford Press.

Sierra, M., & Berrios, G. E. (1998). Depersonalization: neurobiological perspectives. Biological psychiatry, 44(9), 898-908.

Spanos, N. P. (1994). Multiple identity enactments and multiple personality disorder: A sociocognitive perspective. Psychological Bulletin, 116(1), 143-165.

Thomas, L., & Hatch, D. (2017). Emotional Transformation Therapy: An integrative approach to treatment. Routledge.

van der Hart, O., Nijenhuis, E. R., & Steele, K. (2006). The haunted self: Structural dissociation and the treatment of chronic traumatization. W.W. Norton & Co.

Waller, N. G., Putnam, F. W., & Carlson, E. B. (1996). Types of dissociation and dissociative types: A taxometric analysis of dissociative experiences. Psychological Methods, 1(3), 300-321.

Further Reading:

Dell, P. F., & O’Neil, J. A. (Eds.). (2009). Dissociation and the dissociative disorders: DSM-V and beyond. Routledge.

Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence–from domestic abuse to political terror. Basic Books.

Steinberg, M., & Schnall, M. (2000). The stranger in the mirror: Dissociation–the hidden epidemic. Harper Collins.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

Boon, S., Steele, K., & van der Hart, O. (2011). Coping with trauma-related dissociation: Skills training for patients and therapists. W. W. Norton & Company.

Chu, J. A. (2011). Rebuilding shattered lives: Treating complex PTSD and dissociative disorders. John Wiley & Sons.

Nijenhuis, E. R. S. (2015). The trinity of trauma: Ignorance, fragility, and control. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Steele, K., Boon, S., & van der Hart, O. (2017). Treating trauma-related dissociation: A practical, integrative approach. W. W. Norton & Company.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

0 Comments