Executive Summary: The Courage of Imperfection

The Cultural Trap: We live in a society obsessed with the “Persona”—the mask of perfection. We hide our pain, treating vulnerability as a defect rather than a biological necessity.

The Science of Connection: According to Dr. Stephen Porges’ Polyvagal Theory, mental health is not an individual task. Our nervous systems require “Co-Regulation” with safe others to function. Isolation is physically toxic.

The Path Forward: Healing requires moving from “Symptom Management” (hiding the cracks) to “Post-Traumatic Growth” (highlighting the repairs, like Kintsugi). By embracing the “Wounded Healer” archetype, we create a society resilient enough to handle the reality of being human.

Why Should I Care About Mental Health? Embracing Vulnerability in a Perfectionist Culture

Our culture is obsessed with optimization. We use technology to curate avatars of perfection, convincing ourselves and others that our lives are flawless, productive, and pain-free. This facade is what Jungians call the Persona—the mask we wear to survive social interactions. While the Persona is useful for navigating a cocktail party or a job interview, it is disastrous for the soul. When we identify too closely with this mask, we lose the ability to handle the inevitable suffering that life brings.

We live in a society that aggressively sequesters the “unproductive.” We isolate the elderly in homes, we hide the sick in hospitals, and we treat grief as a pathology to be medicated away quickly so we can return to work. By hiding pain from ourselves and our children, we atrophy the emotional muscles required to process it. We create a “Shadow Society” where vulnerability is equated with failure, leaving us ill-equipped when the floor inevitably falls out from under us.

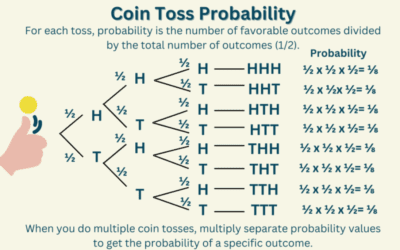

But the data tells a different story. Suffering is not an anomaly; it is a baseline statistic of the human condition. To care about mental health is not to seek a state of permanent happiness; it is to build the resilience required to weather the storms that will inevitably come. It is about recognizing that the “strong” person is not the one who feels nothing, but the one who can feel everything and keep going.

The Biology of Connection: Why We Cannot Heal Alone

There is a pervasive myth in Western culture that mental health is an individual responsibility—a matter of “mindset” or “grit.” However, modern neuroscience refutes the idea of the isolated self. According to Dr. Stephen Porges’ Polyvagal Theory, our nervous systems are not self-contained units; they are wireless networks constantly scanning for safety in the faces and voices of others.

We are biologically wired for Co-Regulation. When we are vulnerable with a safe person, our nervous system moves out of the “Fight or Flight” sympathetic state and into the “Social Engagement” ventral vagal state. This is where healing happens. When we hide our vulnerability to maintain an image of perfection, we deny our nervous system the signal of safety it craves. We remain in a state of chronic, high-functioning anxiety, scanning for threats that aren’t there.

This explains why high-achievers often suffer the hardest crashes. Their success isolates them from the very vulnerability that would regulate their stress. They believe that if they just work harder, they will feel safe. But safety doesn’t come from achievement; it comes from connection.

The Wounded Healer Archetype

As a child, I admired the stoic heroes who seemed impervious to pain. But as I grew older and entered the clinical field, I realized that the most effective healers were not the ones who had avoided suffering, but the ones who had integrated it. In depth psychology, this is known as the Archetype of the Wounded Healer (Chiron).

The therapist’s authority does not come from having a perfect life; it comes from having navigated the darkness and returned with a map. This is why clinical transparency—admitting when we don’t know the answer or when we have made a mistake—is often more therapeutic than expert advice. It models for the patient that one does not need to be perfect to be worthy of love and respect.

When public figures or peers admit to their struggles—be it addiction, depression, or family trauma—they break the spell of shame for everyone listening. Shame acts like a fungus; it grows in the dark and dies in the light. By speaking our shame, we sanitize the wound.

Kintsugi and Post-Traumatic Growth

There is a Japanese art form called Kintsugi, where broken pottery is repaired with gold lacquer. The result is a bowl that is more beautiful and valuable because it has been broken. The cracks are not hidden; they are highlighted.

This is the perfect metaphor for what psychologists call Post-Traumatic Growth. We often view mental health treatment as a way to “get back to normal”—to glue the bowl back together so no one sees the cracks. But true therapy is not about erasing the damage; it is about highlighting the repair. When we process trauma, we do not return to who we were before. We become something new.

We integrate the Shadow parts of ourselves—the fear, the rage, the grief—and in doing so, we become more complex, more empathetic, and more grounded. We move from a fragile perfection to an antifragile resilience.

Moving From “Symptom Management” to “Wholeness”

If we view mental health solely as the absence of symptoms, we miss the point. You can be symptom-free and still be hollow. Improving mental health involves accepting the profound absurdity of the human condition. It means making space for the Lover Archetype’s passion, the Warrior’s aggression, and the Child’s fear.

To foster a healthier society, we must stop outsourcing our pain to the margins. We must stop pretending that the “sane” people are inside the castle and the “crazy” people are outside the walls. We are all on the spectrum of suffering. Recognizing this interconnectedness is the only way to build a world that is safe enough for us to be human. When we embrace our own brokenness, we give permission for others to do the same, creating a community bound not by perfection, but by shared humanity.

Bibliography

- Brown, B. (2012). Daring Greatly: How the Courage to Be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent, and Lead. Gotham Books.

- Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Viking.

- Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-regulation. W.W. Norton & Company.

- Becker, E. (1973). The Denial of Death. Free Press.

- Jung, C. G. (1959). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton University Press.

0 Comments