When Fantasy Meets Therapy

In recent years, mental health professionals have begun discovering what millions of players worldwide have long suspected: there’s something profoundly therapeutic about gathering around a table to embark on imaginary adventures. Dungeons & Dragons (D&D), once stigmatized as an obscure hobby, has emerged as a powerful tool for developing emotional regulation, social skills, and metacognitive awareness in both children and adults.

This transformation from tabletop game to therapeutic intervention represents a fascinating convergence of play therapy, narrative psychology, and experiential learning. As mental health services seek innovative approaches to engage clients—particularly those who struggle with traditional talk therapy—D&D offers a unique pathway to emotional growth through the safe distance of fantasy role-play.

Understanding Role-Playing Games: A Primer for Therapists

What Is Dungeons & Dragons?

At its core, D&D is a collaborative storytelling game where players create characters and navigate adventures guided by a Dungeon Master (DM). Unlike traditional board games, D&D has no predetermined path or winner. Instead, players use dice to determine the outcomes of their actions while collectively creating a narrative through their choices and interactions.

The game operates on a simple premise: players describe what they want their characters to do, roll dice to determine success or failure, and deal with the consequences. This seemingly straightforward mechanic creates a rich playground for exploring decision-making, consequence management, and emotional responses in a controlled environment.

The Character Creation Process: Building an Avatar for Growth

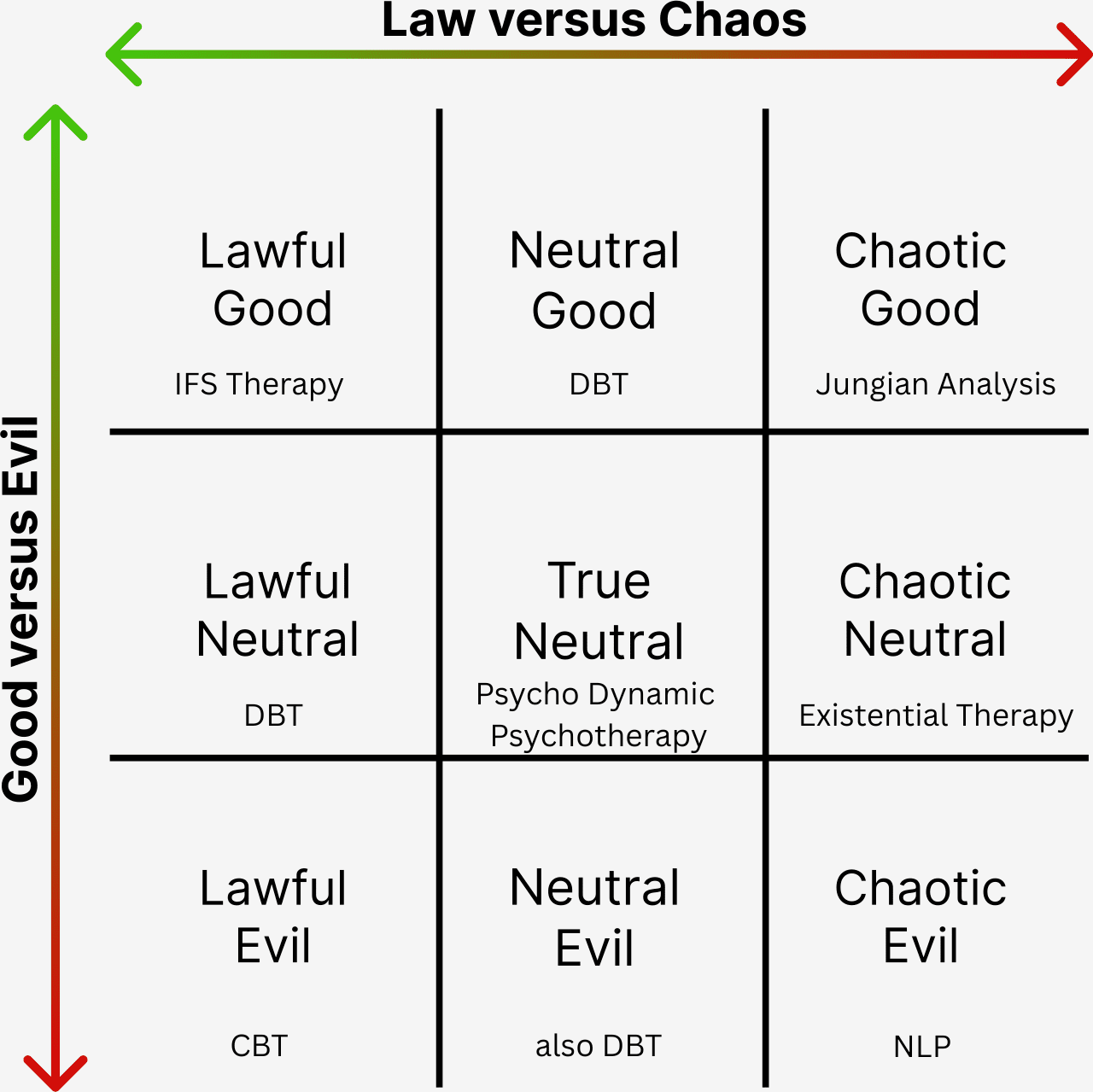

Character creation in D&D begins with fundamental choices that mirror real-world identity formation. Players select a race (elf, human, dwarf), class (warrior, wizard, rogue), and background that shapes their character’s abilities and perspective. But perhaps most significantly for therapeutic purposes, players choose an alignment—a moral and ethical orientation that guides their character’s decisions.

The alignment system operates on two axes: law versus chaos, and good versus evil. This creates nine possible alignments, from Lawful Good (the principled hero) to Chaotic Evil (the unpredictable villain). This framework provides a structured way to explore moral reasoning and ethical decision-making, allowing players to experiment with different value systems and their consequences.

During character creation, players also develop backstories, motivations, and personality traits. This process itself can be therapeutic, as players often unconsciously project their own struggles, aspirations, and coping mechanisms onto their characters. A shy child might create a bold warrior, testing assertiveness in a safe space. An adult struggling with rigid thinking might play a chaotic character, exploring flexibility through fantasy.

The Therapeutic Mechanisms of D&D

Confronting Pathological Elements of Identity

Role-playing games provide what therapists call “surplus reality”—a space where individuals can safely explore aspects of themselves that feel too dangerous or vulnerable to express directly. Through their characters, players can confront fears, practice new behaviors, and process difficult emotions without the real-world stakes that make change so challenging.

The game creates natural opportunities for identity exploration. Players might discover that the evil character they created doesn’t align with their actual values when faced with moral dilemmas. This dissonance becomes a powerful catalyst for self-reflection and growth. The character serves as both a mask that provides safety and a mirror that reflects hidden aspects of the self.

Developing Metacognition Through Play

One of D&D’s most powerful therapeutic elements is its ability to foster metacognition—thinking about thinking. The game constantly requires players to step outside their immediate reactions and consider multiple perspectives: their own, their character’s, other players’, and the various non-player characters they encounter.

This metacognitive practice manifests in several ways:

Perspective-Taking: Players must constantly shift between their own knowledge and what their character would know, developing theory of mind and empathy.

Strategic Planning: The game requires thinking several steps ahead, considering potential consequences, and adapting when plans go awry.

Emotional Reflection: After intense scenes, groups often naturally debrief, discussing why characters (and players) reacted as they did.

Decision Analysis: The explicit nature of choice in D&D—”What do you do?”—creates countless opportunities to examine decision-making processes and their emotional underpinnings.

Emotion Regulation Through Structured Play

For Children: Learning Through Adventure

Children often struggle to articulate complex emotions or understand the connection between feelings and behaviors. D&D provides a structured framework for exploring these connections through experiential learning rather than direct instruction.

Identifying Emotions in Context: When a character faces danger, betrayal, or triumph, children naturally discuss the emotions involved. “My character feels angry because the villain hurt their friend” becomes a gateway to discussing anger, justice, and appropriate responses to harm.

Practicing Emotional Responses: The game allows children to test different emotional strategies. A child whose character typically responds with aggression might discover that negotiation or stealth sometimes yields better results, translating to real-world emotion regulation strategies.

Building Frustration Tolerance: D&D involves failure—dice rolls go badly, plans fall apart, characters face setbacks. Within the game’s structure, children learn that failure isn’t catastrophic but part of the adventure, building resilience and frustration tolerance.

Developing Emotional Vocabulary: The narrative nature of D&D naturally expands emotional vocabulary as children describe their characters’ internal states and motivations.

For Adults: Reconnecting with Play and Processing Complex Emotions

Adults often arrive at therapy disconnected from play, viewing it as childish or unproductive. D&D challenges this notion, providing sophisticated narrative experiences that engage adult cognitive abilities while reconnecting them with the healing power of imagination.

Bypassing Intellectual Defenses: The fantasy setting allows adults to explore emotions and relationships without triggering the defensive mechanisms that often arise in direct therapeutic conversation.

Processing Trauma and Loss: Through their characters’ journeys, adults can symbolically revisit and reprocess difficult experiences. A character’s quest for revenge might evolve into a journey of forgiveness, mirroring the player’s own emotional evolution.

Experimenting with Vulnerability: The collaborative nature of D&D requires trust and vulnerability—asking for help, admitting mistakes, celebrating others’ successes. These experiences can be transformative for adults who struggle with perfectionism or emotional isolation.

Practicing Assertiveness and Boundaries: The game provides structured opportunities to practice saying no, setting limits, and advocating for oneself through character interactions.

The Power of Alignment: Moral Development Through Choice

One of the most fascinating therapeutic applications of D&D involves the alignment system and its impact on moral reasoning. The game creates what researchers call a “moral laboratory” where players can experiment with ethical decisions and experience their consequences without real-world harm.

The Journey from Evil to Good

Particularly striking are cases where players, especially children, initially create evil-aligned characters, only to discover discomfort with acting out these alignments in practice. When faced with scenarios requiring cruelty or selfishness—even in fantasy—many players experience moral distress that leads to profound self-reflection.

For instance, a child who creates a Chaotic Evil rogue might find themselves reluctant to steal from innocent shopkeepers or harm defenseless creatures. This disconnect between initial character concept and actual play preferences opens discussions about values, empathy, and moral intuition. The game makes abstract ethical concepts concrete and personal.

Acting “Out of Alignment”: The Growth Zone

D&D includes mechanical consequences for acting against one’s alignment, creating teachable moments about integrity and authentic self-expression. When players choose to have their evil characters perform good acts—accepting penalties to save innocents or help party members—they demonstrate moral growth that transcends game mechanics.

These “alignment shifts” often reflect real psychological development. A player might begin with a rigid, Lawful Neutral character who follows rules without question, then gradually develop toward Neutral Good as they learn to balance principles with compassion. This evolution mirrors real-world moral development from conventional to post-conventional reasoning.

Emotional Regulation in Action: The Pause Between Impulse and Action

One of D&D’s most powerful therapeutic mechanisms is the natural pause it creates between emotional impulse and action. When a player declares, “I want to attack the guard who insulted me,” the game’s structure intervenes: “Okay, roll for initiative.” This pause—the time it takes to pick up dice, calculate modifiers, and await results—creates space for second thoughts and group intervention.

Learning from Consequences

The game’s consequence system teaches emotion regulation through experience rather than instruction. A player whose character consistently acts on anger might find themselves:

- Alienating non-player characters who could provide crucial information

- Triggering unnecessary combat that depletes party resources

- Creating reputation consequences that complicate future interactions

- Facing party members’ frustration with disruptive behavior

These in-game consequences create low-stakes learning opportunities. Players discover that emotional dysregulation, even in fantasy, has social and practical costs. More importantly, they learn this through experience rather than lecture, making the lessons more impactful and memorable.

The Party as Emotional Support System

The collaborative nature of D&D means players must consider how their emotional expressions affect others. A character’s rage-fueled rampage might endanger the party, leading to natural group discussions about managing strong emotions. Party members might develop in-game strategies for helping each other regulate—the bard plays soothing music, the cleric offers wisdom, the barbarian channels rage productively.

These in-game support systems often mirror and practice real-world emotional support strategies. Players learn to recognize emotional escalation in others, offer co-regulation, and accept help when overwhelmed—all within the safety of fantasy role-play.

Research Evidence: Four Groundbreaking Studies

Study 1: Moral Development Through Imaginative Role-Play (Wright et al., 2020)

Researchers at the College of Charleston conducted a pioneering study with 12 college students who participated in six 4-hour D&D sessions featuring embedded moral dilemmas, such as whether to torture a prisoner for information. Using the Defining Issues Test and Self-Understanding Interview, they found significant growth in moral development in the gaming groups compared to control groups who didn’t play.

The study revealed that players often struggled with moral choices that seemed easy in abstract but proved difficult in practice. Wright et al. concluded that D&D benefitted moral development, especially the expression and maintenance of social interests, with players showing movement toward more sophisticated moral reasoning focused on maintaining relationships while expressing personal values.

Particularly noteworthy was how players negotiated group dynamics when facing ethical dilemmas. The collaborative nature of D&D meant that individual moral choices affected the entire party, creating rich discussions about ethics, consequences, and compromise. Players reported that these in-game moral struggles led them to reconsider real-world ethical positions.

Study 2: Mental Health Improvements Through D&D (James Cook University, 2024)

Researchers at James Cook University studied 25 participants with a mean age of 28 who played eight one-hour D&D sessions over eight weeks. Participants demonstrated significant decreases in depression, stress, and anxiety, along with significant increases in self-esteem and self-efficacy over the study period.

The study involved players tracking a goblin through a cave system after it had stolen from a town, facing monsters and traps throughout the pursuit. Participants reported that D&D provided cathartic emotional expression and a safe space to explore mental health challenges without concern for outside consequences.

The structured nature of the intervention—regular sessions with consistent groups—created a supportive community that extended beyond the game itself. Participants formed connections that provided social support, reducing isolation and creating accountability for attendance and engagement.

Study 3: University College Cork Study on Escapism and Self-Exploration (2024)

University College Cork researchers found that D&D benefits mental health by providing escapism, self-exploration, and social support. The game’s collaborative and creative nature fosters a sense of control and emotional connection, helping players deal with real-life feelings of powerlessness.

The study identified three key mechanisms through which D&D supports mental health:

- Positive Escapism: Unlike maladaptive escapism that avoids problems, D&D provides structured breaks from reality that refresh and restore rather than enable avoidance.

- Identity Experimentation: Players safely explore different aspects of personality and identity through character play, integrating these experiences into their self-concept.

- Social Connection: The collaborative storytelling aspect of D&D fosters a unique sense of camaraderie and shared experience among players, providing emotional and social connection in a space where participants can express themselves freely.

Study 4: Rapid Evidence Assessment of D&D’s Therapeutic Utility (Henrich & Worthington, 2021)

In a comprehensive rapid evidence assessment, researchers found that D&D provides a structured space for clients to explore attachment-related behaviors, practice emotional regulation, and develop healthier relationships. Through role-playing, players can experiment with trust, communication, and boundary-setting in a safe environment.

The review highlighted D&D’s ability to address trauma, noting that the game facilitates recovery by integrating storytelling, role-play, and social collaboration, allowing individuals to externalize trauma narratives and experiment with new identities in a structured environment.

The assessment identified several populations that particularly benefit from D&D therapy:

- Adolescents with social anxiety or autism spectrum disorders

- Adults with depression or anxiety

- Individuals processing trauma or grief

- People with attachment difficulties

- Those struggling with social skills or assertiveness

Implementation in Therapeutic Settings

Individual Therapy Applications

While D&D is inherently social, therapists have successfully adapted elements for individual therapy:

Character Journaling: Clients create characters and write journal entries from their character’s perspective, exploring emotions and experiences through fantasy narrative.

Solo Adventures: Therapists guide clients through single-player scenarios designed to address specific therapeutic goals, such as assertiveness training or anxiety exposure.

Character Analysis: Examining the relationship between client and character choices reveals unconscious patterns, defenses, and aspirations.

Group Therapy Dynamics

D&D naturally creates many dynamics valuable in group therapy:

Peer Support: Party members naturally support each other through challenges, modeling healthy interdependence.

Conflict Resolution: Disagreements about strategy or resources create opportunities to practice negotiation and compromise.

Social Skills Practice: The game requires communication, turn-taking, active listening, and reading social cues.

Leadership Development: Rotating leadership roles as different scenarios favor different character strengths.

Special Populations

Children with ADHD

The structured yet creative nature of D&D can help children with ADHD develop:

- Sustained attention through engaging narrative

- Impulse control through turn-taking mechanics

- Executive function through strategic planning

- Social awareness through group dynamics

Adolescents with Social Anxiety

D&D offers adolescents a structured social activity where interaction is mediated through characters, reducing direct social pressure while building confidence and connections.

Adults with Depression

The game provides behavioral activation—a key treatment for depression—by offering regularly scheduled positive activities that combine creativity, social connection, and achievement.

The Metacognitive Mirror: Reflecting on Thought and Emotion

Recognizing Patterns

Through repeated play, participants begin recognizing their behavioral patterns. A player might notice they always choose combat over negotiation, or that their characters consistently struggle with authority figures. These observations, arising naturally through play rather than therapist interpretation, often feel less threatening and more actionable.

Emotional Forecasting

D&D requires constant emotional forecasting: “If I do X, the NPC will probably feel Y, leading to Z consequence.” This practice strengthens mentalization—the ability to understand mental states in oneself and others. Players develop more sophisticated models of how emotions influence behavior and how behaviors impact relationships.

The Power of Debriefing

Most therapeutic D&D sessions include dedicated debriefing time where players step back from characters to discuss the session. This might involve 60-90 minutes of play followed by 30 minutes of reflection, allowing players to process experiences and connect in-game events to real-life patterns.

During debriefing, therapists might ask:

- “What emotions came up for you during that scene?”

- “Did your character’s reaction surprise you?”

- “What would you have done differently in real life?”

- “What did you learn about yourself through your character today?”

Practical Strategies for Implementation

Starting a Therapeutic D&D Group

- Screen Participants: Ensure group members can tolerate fantasy play and work collaboratively. Screen out individuals with active psychosis or severe personality disorders that might disrupt group dynamics.

- Set Clear Boundaries: Establish that this is therapy with D&D, not just a game. Include consent processes for difficult content and clear policies about attendance and participation.

- Simplify Rules: Use streamlined versions of D&D rules to reduce cognitive load. Focus on narrative and choice rather than complex mechanics.

- Design Therapeutic Scenarios: Create adventures that naturally embed therapeutic goals. A quest to recover a stolen treasure might parallel recovery from loss. A journey through a dark forest might represent depression.

- Train Facilitators: Therapists need both clinical skills and basic D&D knowledge. Consider co-facilitation with an experienced player or DM.

Managing Common Challenges

Power Gaming: Some players focus exclusively on mechanical optimization rather than roleplay. Address this by rewarding character development and emotional engagement rather than just combat success.

Emotional Overwhelm: Fantasy doesn’t always provide enough distance. Have protocols for when players become triggered or overwhelmed, including character “pause” options and grounding techniques.

Group Dynamics: Like any group therapy, interpersonal conflicts arise. Use these as therapeutic opportunities while maintaining safety and respect.

Engagement Variance: Some players naturally engage more than others. Create spotlight moments for quieter players and help dominant players practice stepping back.

Future Directions and Conclusions

The emergence of D&D as a therapeutic tool represents a broader recognition of play’s importance across the lifespan. As digital natives age into adulthood, the distinction between “serious” therapy and “playful” interventions continues to blur. D&D offers a bridge between traditional therapeutic techniques and contemporary culture, speaking to clients in a language they understand and enjoy.

Research consistently demonstrates that D&D can effectively address a range of mental health concerns, from anxiety and depression to social skills deficits and trauma. The game’s unique combination of structure and creativity, safety and challenge, individual agency and group collaboration creates an ideal environment for therapeutic growth.

As we continue to understand the mechanisms through which D&D promotes healing, several areas warrant further investigation:

- Long-term outcomes of D&D therapy interventions

- Optimal group composition and session structure

- Cultural adaptations for diverse populations

- Integration with other therapeutic modalities

- Online versus in-person therapeutic D&D

The magic of D&D as therapy lies not in the fantasy elements themselves, but in how those elements create permission to explore, experiment, and grow. When a shy child finds their voice through a brave paladin, when an isolated adult discovers community through a adventuring party, when someone struggling with rigid thinking learns flexibility through chaotic play—that’s where healing happens.

In a world where traditional therapy can feel intimidating or inaccessible, D&D offers an alternative path to emotional growth. It reminds us that healing doesn’t always require sitting in a chair talking about feelings. Sometimes, healing happens when we roll the dice, face the dragon, and discover that we’re braver than we believed.

Bibliography

Abbott, M. S., Stauss, K. A., & Burnett, A. F. (2022). Table-top role-playing games as a therapeutic intervention with adults to increase social connectedness. Social Work with Groups, 45(1), 16-31.

Adams, A. (2013). Needs met through role-playing games: A fantasy theme analysis of Dungeons & Dragons. Kaleidoscope: A Graduate Journal of Qualitative Communication Research, 12(1), 6.

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Baker, I. S., Turner, I. J., & Kotera, Y. (2022). Role-playing games (RPGs) for mental health (Why not?): Roll for initiative. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(3), 1971-1979.

Blackmon, W. D. (1994). Dungeons and Dragons: The use of a fantasy game in the psychotherapeutic treatment of a young adult. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 48(4), 624-632.

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. Basic Books.

Bratton, S., & Ray, D. (2000). What the research shows about play therapy. International Journal of Play Therapy, 9(1), 47-88.

Chung, T. S. (2013). Table-top role playing game and creativity. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 8, 56-71.

Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135-168.

Feniger-Schaal, R., Noy, L., Hart, Y., Koren-Karie, N., Mayo, A. E., & Alon, U. (2015). Would you like to play together? Adults’ attachment and the mirror game. Attachment & Human Development, 18(1), 33-45.

Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41-54.

Henrich, S., & Worthington, R. (2021). Let your clients fight dragons: A rapid evidence assessment regarding the therapeutic utility of ‘Dungeons & Dragons.’ Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 18(3), 383-401.

Hughes, J. (1988). Therapy is fantasy: Roleplaying, healing and the construction of symbolic order. Paper presented at the Anthropology IV Honours Thesis, Medical Anthropology Seminar, Australian National University.

Kipper, D. A., & Ritchie, T. D. (2003). The effectiveness of psychodramatic techniques: A meta-analysis. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 7(1), 13-25.

Matthews, C., Scrimgeour, A., & Blewitt, L. (2014). Playing with empathy: The use of pen and paper role-playing games in therapy. International Journal of Play, 3(3), 243-258.

Merrick, S. (2024). The impact of Dungeons & Dragons on mental health outcomes in adults. Journal of Gaming and Virtual Worlds, 16(2), 145-162.

Rivers, A., Wickramasekera, I. E., Pekala, R. J., & Rivers, J. A. (2016). Empathic features and absorption in fantasy role-playing. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 58(3), 286-294.

Rosselet, J. G., & Stauffer, S. D. (2013). Using group role-playing games with gifted children and adolescents: A psychosocial intervention model. International Journal of Play Therapy, 22(4), 173-192.

Shapiro, F. (2018). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy: Basic principles, protocols, and procedures (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

Springer, C., Misurell, J. R., & Hiller, A. (2012). Game-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (GB-CBT) group program for children who have experienced sexual abuse: A three-month follow-up investigation. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 21(6), 646-664.

van der Kolk, B. (2019). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin Books.

Verbeke, E., Peeters, W., Kerkhof, I., Bijttebier, P., Steyaert, J., & Wagemans, J. (2018). Lack of motivation to share intentions: How current actions and social feedback impact action prediction in autism. Cognition, 181, 65-79.

White, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. Norton.

White, W. (2017). Dungeons & Dragons: A new path to mental health therapy. Psychology Today, 50(4), 45-52.

Wilson, D. L. (2007). An exploratory study on the players of Dungeons and Dragons [Master’s thesis, Liberty University].

Wong, Y. J. (2012). The psychology of encouragement: Theory, research, and applications. The Counseling Psychologist, 43(2), 178-216.

Wright, J. C., Weissglass, D. E., & Casey, V. (2020). Imaginative role-playing as a medium for moral development: Dungeons & Dragons provides moral training. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 60(1), 99-129.

Zayas, L. H., & Lewis, B. H. (1986). Fantasy role-playing for mutual aid in children’s groups: A case illustration. Social Work with Groups, 9(1), 53-66.

0 Comments