The Intersection of Metallurgy, Spirituality, and Personal Growth

The Japanese katana represents far more than a masterfully crafted weapon—it embodies a rich tapestry of psychological and spiritual traditions that have shaped Eastern philosophy for centuries. This exploration of the katana’s psychological dimensions offers valuable insights for modern therapeutic approaches to personal development, mental clarity, and self-actualization.

The Metallurgical Marvel: Understanding the Katana’s Physical Properties

The katana’s unique construction provides a powerful metaphor for personal integration and resilience. These iconic curved Japanese swords weren’t simply forged—they were meticulously crafted through processes that mirror psychological development.

Japanese blacksmiths discovered that by layering different metals together—hard, rigid steel for the cutting edge combined with softer, more flexible metals for the spine—they could create a blade with seemingly contradictory properties. This lamination process, which often involved folding the metal thousands of times, produced a sword that maintained incredible sharpness while resisting shattering under impact.

The forging process itself involved applying clay along the blade’s edge during the cooling process, creating differential temperatures that produced the katana’s characteristic curve. This wasn’t merely aesthetic—the curve resulted from the varying crystal structures within the metal pulling against themselves, creating internal tension that enhanced the blade’s strength.

This integration of seemingly opposing properties—rigidity and flexibility, hardness and resilience—reflects the psychological integration we seek in personal development. Just as the katana balances these contradictory elements, psychological growth often requires incorporating and balancing opposing aspects of our personality.

The Way of the Warrior: Bushido as Psychological Framework

Following the Mongol invasions of Japan in the 13th century, the samurai class developed a comprehensive ethical and philosophical system known as Bushido (武士道), the “Way of the Warrior.” This code wasn’t merely about combat prowess but encompassed a complete approach to life that integrated psychological disciplines with practical action.

Bushido incorporated elements from Zen Buddhism, Shintoism, and Confucianism, emphasizing:

- Self-discipline: Rigorous training of both mind and body

- Meditation: Cultivating present-moment awareness and mental clarity

- Integration of artistry with martial skill: Many samurai were accomplished poets, calligraphers, and artists

- Moral courage: Acting ethically even at personal cost

- Complete presence: Full engagement with the present moment, especially in combat

These principles find remarkable parallels in modern psychological approaches, particularly mindfulness practices, cognitive-behavioral techniques, and existential therapy. The warrior ethos emphasized a paradoxical truth: true power came not from dominating others but from mastering oneself.

Psychological States in Swordsmanship: Flow and Mental Clarity

The practice of Japanese swordsmanship (kendo, iaido, and related disciplines) cultivates specific psychological states that have remarkable therapeutic applications:

The Empty Mind (Mushin)

Central to Japanese martial arts is the concept of “mushin” (無心)—literally “no mind.” This state, similar to what modern psychology calls “flow,” represents complete absorption in the present moment without self-conscious thought or emotional disturbance.

In swordsmanship, practitioners train to enter this state naturally during combat. Rather than overthinking each move, they respond intuitively with trained reflexes. The goal isn’t unthinking reaction but a higher form of awareness that transcends analytical thought.

Therapeutic applications of this concept include helping clients overcome paralysis by analysis, developing trust in their intuitive responses, and breaking free from rumination cycles that characterize anxiety and depression.

Visualization and Intention

Japanese sword techniques emphasize the importance of clear intention and visualization. When making a cut, the swordsperson doesn’t focus on the object being cut but visualizes the blade continuing through it. This prevents hesitation and allows the full follow-through necessary for clean cuts.

This principle has direct applications in goal-setting and cognitive restructuring therapies. By focusing on the desired outcome rather than the obstacles, clients can maintain momentum through difficulties and avoid self-sabotaging behaviors.

Confidence and Psychological Presence

In traditional sword duels, Japanese masters understood that psychological presence often determined outcomes before swords were drawn. The warrior who harbored doubt was already at a disadvantage. Confidence wasn’t mere bravado but a cultivated state of complete commitment to action.

This understanding has therapeutic parallels in addressing performance anxiety, social phobia, and self-doubt. By cultivating genuine confidence through progressive skill-building and challenging limiting beliefs, clients can develop the psychological presence necessary for effective social and professional engagement.

The Katana as Symbolic Extension of Self

In Japanese tradition, the sword is considered an extension of the warrior’s being, not merely a tool. This perspective offers a powerful framework for understanding the integration of mind and body in therapeutic contexts.

The relationship between samurai and sword models healthy psychological integration in several ways:

- Embodied cognition: Thinking and feeling aren’t abstract processes but are expressed through and influenced by physical action

- Extension of agency: Just as the sword extends the warrior’s reach, therapeutic tools extend a person’s agency into areas previously considered beyond control

- Integration of polarities: The sword embodies both destructive and protective capacities, just as healthy psychological development requires integrating seemingly conflicting aspects of personality

The Trickster and Innovation: Breaking From Tradition

While the stereotype of Japanese sword culture emphasizes rigid tradition, historical examination reveals a fascinating counter-narrative. Many of the most successful swordsmen were innovators who broke from convention, using psychological tactics and creative approaches that defied expectations.

Miyamoto Musashi, Japan’s most famous swordsman, exemplifies this pattern. Despite his legendary status, Musashi frequently employed tactics that more traditional samurai considered dishonorable:

- Arriving late to duels to unnerve opponents

- Using unconventional weapons (once famously using a wooden oar he carved into a sword)

- Positioning himself with the sun at his back to blind opponents

- Employing psychological warfare to anger opponents and disrupt their focus

This tension between tradition and innovation reflects a broader psychological truth: while structured disciplines provide essential foundations, growth often requires transcending established patterns. In therapeutic contexts, this suggests that while evidence-based approaches offer valuable frameworks, practitioners must remain flexible and innovative in adapting techniques to individual client needs.

The Symbolism of Swords Across Cultures

The sword as a psychological symbol transcends Japanese culture, appearing across diverse traditions with remarkably consistent meanings:

Esoteric and Spiritual Traditions

In Western esoteric traditions, the sword represents air energy, associated with intellect, clarity, and the ability to separate truth from falsehood. In ceremonial magic, practitioners use sword-like implements to direct energy and focus intentions.

This air symbolism parallels the Japanese understanding of the sword as an instrument of clarity and precision—cutting through illusion to reveal truth.

The Tarot’s Suit of Swords

The Tarot’s Suit of Swords further elaborates this symbolism, representing:

- Intellectual clarity and rational thought

- Decisiveness and the ability to separate

- The challenges that come from overthinking

- The “double-edged” nature of intellect—capable of both insight and self-deception

Cards like the Six of Swords show people carrying their “swords” (accumulated wisdom and painful lessons) as they transition to new life phases—suggesting that even as we heal, we bring forward the insights gained through difficulty.

Jungian Interpretation

From a Jungian perspective, the sword represents the discriminating function of consciousness—the ability to make distinctions and establish boundaries. This function is essential for psychological development but must be balanced with inclusive, connective awareness to avoid becoming rigidly divisive.

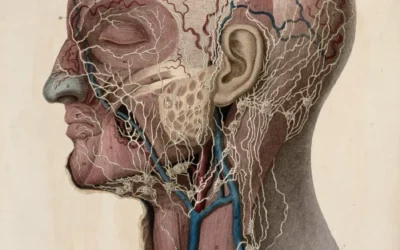

Physical Posture and Psychological Power

The physical stance of holding a sword has direct psychological implications. In various yogic and somatic practices, postures that mimic the stance of a warrior holding a sword are used to cultivate feelings of agency and power.

These postures typically involve:

- Upright spine and expanded chest

- Arms extended forward or upward

- Grounded, stable lower body

- Directed gaze and focused attention

Somatic psychologists note that assuming these postures can help clients overcome feelings of powerlessness, particularly when trauma has disconnected them from their sense of agency. The physiological feedback from these postures helps recalibrate the nervous system’s understanding of personal capability.

The Death Poem Tradition and Mortality Awareness

An intriguing aspect of samurai culture was the “death poem” tradition, where warriors composed short haiku-like verses in anticipation of death. These poems often contained profound observations about life’s transience and the nature of consciousness.

Examples include meditations on identity as temporary and flowing: “We are icicles melting, returning to the stream” or “Your whole life you are a paper doll drifting in a river that a child has dropped, but eventually the river reaches the sea.”

This practice represents an early form of what existential therapists now recognize as mortality awareness—the understanding that conscious engagement with our finite nature can paradoxically lead to more meaningful and authentic living.

The Psychology of Test Cutting: Transcending Hesitation

In advanced sword training, students eventually practice tameshigiri (試し切り)—test cutting with real blades on standardized targets. This practice reveals profound psychological insights about hesitation and commitment.

Instructors emphasize that successful cutting requires:

- Visualizing beyond the target: Focusing not on the object but through it

- Complete commitment: Any hesitation or doubt guarantees failure

- Flowing movement: Allowing the blade to slice rather than chop

- Mental preparation: Psychological readiness determines physical success

These principles have direct therapeutic applications for addressing procrastination, commitment issues, and performance anxiety. By identifying how anticipatory thoughts create hesitation and developing techniques to maintain momentum through decision points, clients can overcome self-sabotaging patterns.

Integration of Art and Combat: Creative Expression as Psychological Balance

A remarkable aspect of samurai culture was the expectation that warriors would also be accomplished in artistic domains—poetry, calligraphy, flower arranging, or tea ceremony. This wasn’t mere cultural refinement but reflected a deep understanding of psychological balance.

The integration of artistic expression with martial skill served several psychological functions:

- Emotional regulation: Creative expression provided channels for processing emotions that couldn’t be expressed in combat contexts

- Perspective expansion: Artistic practice cultivated sensitivity and aesthetic awareness that balanced the warrior’s necessary capacity for detachment

- Whole-person development: The combination prevented psychological over-specialization and one-dimensional identity formation

Modern therapeutic approaches like art therapy and expressive arts therapy build on this understanding, recognizing that integrating multiple modes of expression fosters psychological resilience and adaptability.

Androgyny and Psychological Wholeness

An intriguing aspect of Japanese sword culture is how the ultimate mastery was often depicted with androgynous qualities. While the journey begins with heavily masculine-coded qualities (strength, assertiveness, direct action), the highest levels of mastery incorporate traditionally feminine-coded qualities (fluidity, receptivity, intuitive response).

This pattern reflects a psychological truth recognized across traditions: complete development requires integrating both masculine and feminine principles regardless of one’s gender identity. The most effective warriors weren’t hypermasculine but balanced—capable of fierce action and gentle restraint, strategic planning and intuitive response.

In Jungian terms, this represents the integration of anima and animus—the recognition that psychological wholeness requires incorporating aspects of personality traditionally associated with both genders.

Contemporary Applications: The Katana’s Lessons in Modern Therapy

The psychological wisdom embedded in Japanese sword traditions offers valuable applications for contemporary therapeutic approaches:

Mindfulness and Attention Training

The focused attention cultivated in sword practice has direct parallels to mindfulness-based interventions. Both develop:

- Present-moment awareness

- Reduced mind-wandering

- Capacity to redirect attention

- Non-judgmental observation

Integration of Body and Mind

Somatic approaches to therapy recognize what sword traditions have long understood—that psychological states are embodied and that physical practices can transform mental patterns. The sword practitioner’s integration of posture, breathing, attention, and intention models the holistic approach needed for lasting psychological change.

Confidence Building and Agency

The progressive skill development model of swordsmanship provides a template for building genuine confidence. Rather than empty affirmations, this approach builds self-efficacy through:

- Mastering progressively challenging skills

- Receiving immediate feedback

- Experiencing direct evidence of capability

- Recognizing improvement over time

Balance of Tradition and Innovation

The tension between traditional forms and innovative adaptability in sword culture mirrors a healthy approach to therapeutic techniques—respecting established methods while remaining flexible enough to adapt to individual needs.

The Sword as Path to Integration

The katana’s psychological significance ultimately lies in its function as a path to integration—bringing together opposing forces, balancing contradictory qualities, and unifying body and mind. Just as the sword itself integrates hardness and flexibility, the way of the sword integrates discipline and spontaneity, tradition and innovation, power and restraint.

In our fragmented modern lives, this model of integration offers a compelling vision of psychological wholeness—not as static perfection but as dynamic balance, not as absence of conflict but as the ability to hold tension creatively.

The psychological wisdom of the katana reminds us that the path to wholeness requires both cutting away what isn’t essential and protecting what is valuable—discernment and commitment united in purposeful action.

0 Comments