Subconscious vs Unconscious: The Epic Split Between Jung and Freud That Still Divides Psychology Today

Introduction: When Giants Collide

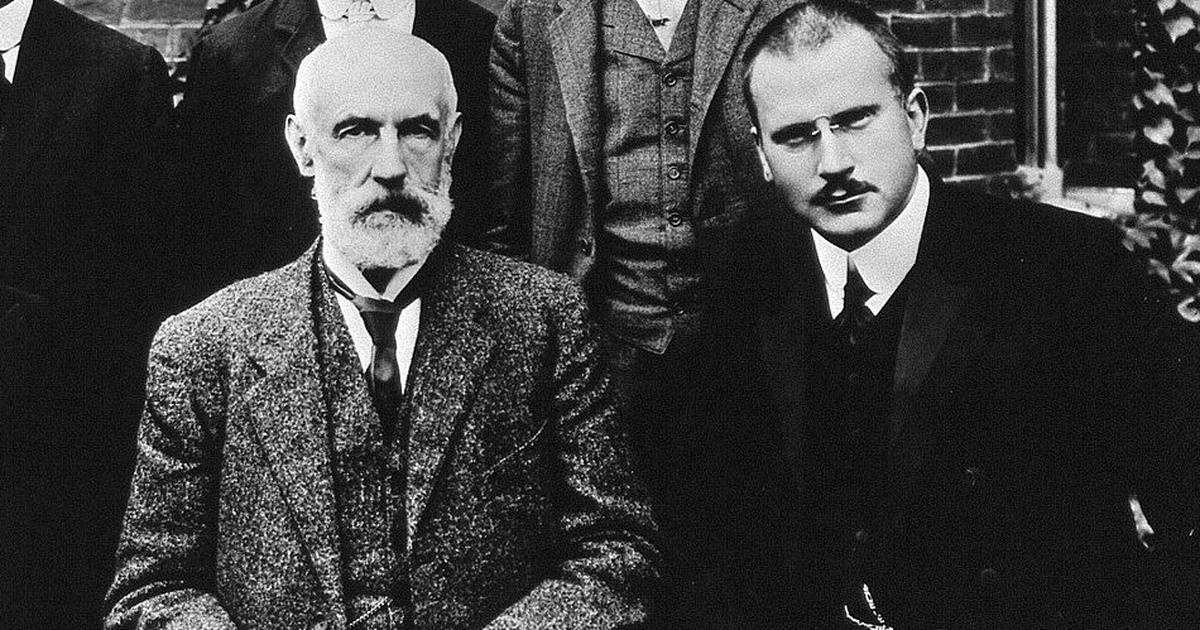

The relationship between Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung represents one of the most dramatic breakups in intellectual history. What began as a passionate friendship between mentor and protégé in 1907 ended in bitter acrimony by 1913, creating a schism in psychology that persists over a century later. Their split wasn’t merely personal—it fundamentally shaped how we understand the human mind, creating two distinct schools of thought that continue to influence modern psychotherapy.

The Golden Years: A Meeting of Minds (1907-1909)

When Freud and Jung first met in Vienna in March 1907, they talked non-stop for thirteen hours. Freud, then 51, saw in the 31-year-old Jung his intellectual heir—his “Joshua” who would lead psychoanalysis into the promised land. Jung, for his part, found in Freud a father figure and mentor who understood his revolutionary ideas about the human psyche.

Their correspondence during this period reveals an intense intellectual and emotional bond. Freud wrote of Jung: “Your person has filled me with confidence in the future,” while Jung expressed his “unconditional veneration” for Freud. Together, they traveled to America in 1909, delivering lectures at Clark University that would introduce psychoanalysis to the New World.

The Seeds of Discord: Why Did Freud and Jung Split?

The Sexuality Debate: The Core Theoretical Divide

The fundamental disagreement centered on the role of sexuality in human psychology. Freud insisted that sexual drive (libido) was the primary motivator of all human behavior, viewing even seemingly unrelated activities through this lens. Jung, however, believed human motivation stemmed from a broader “life force” encompassing creativity, spirituality, and intellectual pursuits. This difference would prove irreconcilable.

The Unconscious: Different Visions

Their conceptions of the unconscious mind diverged dramatically. Freud’s unconscious was a dark repository of repressed sexual and aggressive desires, while Jung’s unconscious was a creative force containing both personal experiences and a collective unconscious shared by all humanity. This fundamental difference reflected their broader orientations: Freud’s focus on pathology and repression versus Jung’s interest in growth, meaning, and universal human experiences.

Religion and Spirituality: Science vs. Soul

Freud viewed religion as an illusion and neurosis, while Jung saw it as a fundamental aspect of the human psyche deserving serious study. This difference reflected their backgrounds—Freud as a secular Jew committed to scientific materialism, Jung as a Swiss Protestant interested in mysticism and spirituality. Jung’s openness to spiritual experiences would become one of Freud’s primary criticisms.

Personal Dynamics: Father, Son, and Power

The relationship dynamics proved toxic from the start. Freud needed disciples who would accept his theories without question, while Jung had his own ideas and refused to be anyone’s intellectual subordinate. Both men had strong personalities and were unwilling to compromise, creating an inevitable collision course.

The Occult Incident: The Breaking Point

A dramatic incident in 1909 foreshadowed the split. When Freud dismissed Jung’s interest in parapsychology, Jung felt his diaphragm become red-hot, and a loud crack emanated from Freud’s bookcase. Jung predicted it would happen again—and it did. Freud was deeply disturbed by this apparent poltergeist phenomenon, seeing it as evidence of Jung’s dangerous mysticism. This incident crystallized Freud’s fears about Jung’s interest in the occult.

Letters of Reconciliation: Attempts to Heal the Rift

Emma Jung’s Intervention

Emma Jung, Carl’s wife, attempted to mediate between the two men. In a remarkable letter to Freud in November 1911, she wrote: “You may imagine how overjoyed and honored I am by the confidence you have in Carl, but it almost seems to me as though you were sometimes giving him too much—do you not see in him the follower and fulfiller more than you need? Doesn’t one often give much because one wants to keep much?” She perceptively identified the unhealthy dynamics, noting that Freud’s need for an intellectual heir was placing impossible demands on her husband.

Friends and Colleagues Urge Reconciliation

Several mutual colleagues attempted to bridge the gap during this period. Sándor Ferenczi wrote to both men urging moderation, while Karl Abraham initially tried to mediate before siding firmly with Freud. Ernest Jones attempted diplomatic solutions while ultimately remaining loyal to Freud. Despite these efforts, both men proved intractable. Their last meeting in September 1913 at the Munich Congress ended with Jung’s resignation from his psychoanalytic positions.

The Break-Up Letter: Freud’s Final Word (January 3, 1913)

Freud’s letter severing their relationship remains a masterpiece of controlled fury: “Your allegation that I treat my followers as patients is demonstrably untrue… It is a convention among us analysts that none of us need feel ashamed of his own neurosis. But one [meaning Jung] who while behaving abnormally keeps shouting that he is normal gives ground for the suspicion that he lacks insight into his illness. Accordingly, I propose that we abandon our personal relations entirely.”

He continued with cutting precision: “I shall lose nothing by it, for my only emotional tie with you has been a long thin thread — the lingering effect of past disappointments — and you have everything to gain, in view of the remark you recently made to the effect that an intimate relationship with a man inhibited your scientific freedom.”

Freud’s Posthumous Attacks: A Campaign of Dismissal

The “Black Tide of Mud” Comment

Jung later recalled a conversation where Freud begged him never to abandon the sexual theory: “You see we must make a dogma of it, an unshakable bulwark.” When Jung asked, “A bulwark—against what?” Freud replied, “Against the black tide of mud…of occultism.” This exchange revealed Freud’s deep anxiety about Jung’s spiritual interests and his determination to keep psychoanalysis within strictly materialist bounds.

Pathologizing Jung’s Ideas

In his 1914 work “On the History of the Psycho-Analytic Movement,” Freud launched a systematic attack on Jung’s theoretical innovations. He dismissed Jung’s broader concept of libido as unscientific, characterized Jung’s theoretical innovations as neurotic defenses against accepting the primacy of sexuality, and accused Jung of diluting psychoanalysis to make it more palatable to a resistant public. According to historical documents, Freud’s critique was as much personal as theoretical.

The “Mystic” Label

Freud and his followers consistently branded Jung as a “mystic,” using the term pejoratively to dismiss his contributions. They belittled his discoveries and portrayed his interest in spirituality as evidence of mental instability. This campaign of marginalization continued for years after their split, with Freud’s inner circle maintaining a united front against Jungian ideas.

Private Character Assassinations

In letters to colleagues, Freud expressed relief at being rid of Jung, attributed Jung’s defection to character flaws rather than legitimate theoretical differences, suggested Jung’s Swiss Protestant background made him unsuitable for psychoanalysis, and claimed Jung’s theories were motivated by personal neurosis rather than scientific insight. These private communications reveal the depth of Freud’s animosity.

Jung’s Criticisms of Freud: The Other Side

Dogmatism and Rigidity

Jung’s primary criticism was Freud’s inflexibility: “His regrettable dogmatism was the main reason why I felt obliged to part company with him. My scientific conscience would not allow me to lend support to an almost fanatical dogma based on a one-sided interpretation of the facts.” Jung saw Freud’s insistence on sexual theory as a form of intellectual tyranny that stifled genuine scientific inquiry.

Reductionism

Jung objected to Freud’s tendency to reduce all human experience to sexuality. He saw this approach as overly simplistic, argued it ignored spiritual and creative dimensions of life, and believed it reflected Freud’s own neuroses rather than universal human truths. For Jung, human beings were far more complex than Freud’s theory allowed.

Materialism

Jung criticized Freud’s purely biological approach to the psyche. He felt it denied the reality of spiritual experiences, argued it couldn’t explain the full range of human consciousness, and saw it as culturally limited to 19th-century scientific materialism. Jung believed psychology needed to acknowledge the transcendent aspects of human experience.

Personal Observations

Jung noted several troubling aspects of Freud’s personality: his inability to tolerate disagreement, his need for absolute loyalty from followers, his fear of examining his own unconscious, and his anxiety about his theories being challenged. Jung saw these traits as evidence that Freud had not fully analyzed himself, despite advocating self-analysis for others.

Were Their Mutual Criticisms Fair? A Balanced Assessment

Validity of Freud’s Criticisms

Freud made some fair points about Jung’s approach. Jung did incorporate non-scientific elements into his theories, some of Jung’s concepts are difficult to test empirically, and Jung’s writing could indeed be mystical and obscure. However, Freud’s approach was often unfair in pathologizing theoretical disagreements as mental illness, dismissing all spiritual interests as “occultism,” refusing to engage with Jung’s ideas on their merits, and using ad hominem attacks rather than substantive critique.

Validity of Jung’s Criticisms

Jung’s criticisms also had merit. Freud was demonstrably dogmatic about his theories, sexual reductionism was limiting, Freud did demand uncritical acceptance from followers, and psychoanalysis needed broader perspectives. Yet Jung was sometimes unfair in minimizing Freud’s genuine contributions, occasionally misrepresenting Freud’s positions, making personal attacks on Freud’s character, and dismissing the importance of sexuality entirely.

The Feud Continues: Modern Echoes of an Old Battle

Institutional Divisions

The split created lasting institutional separations that persist today. The International Psychoanalytical Association represents the Freudian tradition, while the International Association for Analytical Psychology carries on Jung’s work. These organizations maintain separate training institutes that rarely collaborate, different journals and conferences, and distinct theoretical frameworks that often seem incompatible.

Theoretical Battles

Contemporary debates continue to echo the original split. Therapists still argue about the role of spirituality in therapy, the importance of cultural and mythological factors, the nature of the unconscious, and whether to prioritize evidence-based or meaning-based approaches. These debates often replay the fundamental disagreements between Freud and Jung.

Recent Attempts at Reconciliation

The Philemon Foundation, dedicated to publishing Jung’s works, issued a statement in 2010 calling for “moving beyond the historical animosity to recognize the complementary insights of both pioneers.” A landmark conference in Vienna in 2019 brought together Freudian and Jungian analysts to explore common ground, with keynote speaker Dr. Murray Stein noting: “The time has come to heal this century-old wound in the psyche of depth psychology.”

The COVID-19 pandemic created unexpected dialogue between the schools from 2020-2023. Therapists from both traditions collaborated on treating collective trauma, recognized the need for both approaches in addressing unprecedented challenges, shared techniques for online therapy, and published joint papers on societal healing. This crisis-driven cooperation suggested new possibilities for integration.

Notable Recent Developments

The Zurich Declaration of 2022 saw leaders from major psychoanalytic and Jungian institutes sign a document acknowledging “the value of diverse approaches to understanding the human psyche.” Several institutes now offer cross-training programs in both traditions, and a growing number of therapists identify as “psychodynamic” rather than strictly Freudian or Jungian, suggesting a movement toward integration.

The Hidden Influence: Why Jung and Adler Won the Long Game

The Paradox of Recognition

While Freud remains the most famous name in psychology, Jung and Alfred Adler‘s ideas have arguably had greater practical influence in contemporary culture and therapy.

Jung’s Mainstream Victories

Jung’s concept of introversion and extraversion has become universal personality categories, forms the basis for the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), and is used by millions in corporate settings worldwide. The notion of psychological complexes entered everyday language through terms like “inferiority complex,” “God complex,” and “hero complex,” becoming accepted concepts in mainstream therapy.

Jung’s archetypes profoundly influenced storytelling through the hero’s journey narrative structure, personal development through shadow work, and our understanding of universal human experiences through the collective unconscious in film and literature. His concept of individuation sparked the self-actualization movement, the personal growth industry, and influenced mindfulness and meditation practices. Active imagination techniques evolved into visualization methods, creative therapies, and guided imagery in healing.

Therapeutic practices derived from Jung include dream work that goes beyond sexual interpretation, sand play therapy, art therapy, and the integration of spirituality in counseling. These approaches have become mainstream without always being recognized as Jungian in origin.

Adler’s Quiet Revolution

Alfred Adler, who wisely avoided the Freud-Jung feud, achieved remarkable influence through different channels. His concept of the inferiority complex became a standard psychological term, a basis for understanding motivation, and a foundation for the self-help industry. Birth order theory gained wide acceptance in popular psychology, influences parenting advice based on sibling position, and informs personality assessments.

Adler’s lifestyle assessment approach promoted a holistic view of therapy, contributed to work-life balance concepts, and influenced the wellness movement. His emphasis on social interest shaped community mental health approaches, group therapy methods, and the integration of social justice in psychology. Practical applications of Adlerian ideas permeate school counseling programs, parent education, marriage counseling, and career counseling.

Why the “Losers” Won

Jung and Adler’s ideas proved more accessible and adaptable to everyday life than strict Freudian orthodoxy. Their less dogmatic approach allowed evolution and integration with other therapeutic modalities. They focused on growth and potential rather than pathology, better aligning with American optimism and spirituality. Their broader scope addressed creativity, spirituality, and social factors that Freudian analysis often overlooked.

Modern Integration: Beyond the Feud

Emerging Syntheses

Contemporary approaches increasingly combine insights from multiple traditions. Psychodynamic therapy integrates various perspectives, depth psychology honors both Freudian and Jungian contributions, and integrative psychotherapy uses techniques from all schools. The rigid boundaries that once separated these approaches are becoming more permeable.

Common Ground Rediscovered

Modern therapists recognize that both pioneers contributed essential insights. The unconscious exists and influences behavior, early experiences shape personality, dreams and symbols carry important meaning, the therapeutic relationship proves crucial for healing, and integration of split-off parts of the psyche promotes wholeness. These shared understandings form the foundation for contemporary depth psychology.

The Future of Depth Psychology

The field increasingly recognizes complementary rather than competing truths in different approaches. Practitioners integrate neuroscience with depth psychological insights, address cultural and collective trauma using multiple perspectives, and develop new models that transcend old divisions. The future lies not in choosing sides but in synthesizing wisdom from all traditions.

Conclusion: The Wound That Became a Gift

The Freud-Jung split, painful as it was, ultimately enriched psychology by creating multiple perspectives on the human psyche. While their personal relationship could not be healed, their intellectual legacies continue to evolve and, increasingly, to converge.

Perhaps Emma Jung was prophetic when she wrote to Freud: “The fate of great minds is to be misunderstood by their contemporaries but vindicated by history.” Both men were partially right, partially wrong, and wholly human in their strengths and limitations.

As we face the complexities of 21st-century mental health—from digital addiction to climate anxiety, from social isolation to spiritual hunger—we need all the wisdom we can gather. The time has come to move beyond the century-old feud and integrate the best insights from all depth psychological traditions.

The subconscious and unconscious, however we conceive them, remain mysterious realms that humble our attempts at final understanding. In that humility lies the possibility of healing—not just for individuals, but for a profession still bearing the scars of its founding fathers’ bitter divorce.

Epilogue: A Letter Never Sent

In Jung’s private papers, discovered after his death, was found an unsent letter to Freud dated 1960: “Dear Professor, The years have not dimmed my gratitude for what you taught me, nor my regret for how we parted. Perhaps we were both right, both wrong, both necessary. The psyche, it seems, is large enough to contain our contradictions. Your former colleague, C.G.J.”

Whether authentic or apocryphal, it captures what might have been—and what still might be—if we can learn from their mistakes while honoring their contributions.

For further reading on integrative approaches to depth psychology, explore our recommended resources and training programs that honor both Freudian and Jungian traditions. Visit the C.G. Jung Institute or the International Psychoanalytical Association for more information on their respective approaches.

0 Comments