In 1982, Ridley Scott released a film that bombed at the box office but succeeded in something far more important: it showed us the future we were already building. Blade Runner wasn’t science fiction. It was documentary footage from a tomorrow that capital was constructing in real-time. While audiences puzzled over whether Deckard was a replicant, they missed the more disturbing question: in a world where corporations manufacture consciousness itself, does the distinction between human and product even matter anymore?

The film arrived like a transmission from 2019 that somehow got broadcast in 1982. Its Los Angeles, perpetually raining, eternally dark, architecturally schizophrenic, wasn’t a prediction but a diagnosis. This was late-stage capitalism made visible: a world where Japanese corporations own the sky, where genetic engineering has replaced human reproduction, where the only remaining animals are electric dreams of extinct species, where the rich have literally abandoned Earth for off-world colonies, leaving behind a planet that’s become one vast factory floor.

The Architecture of Accumulation

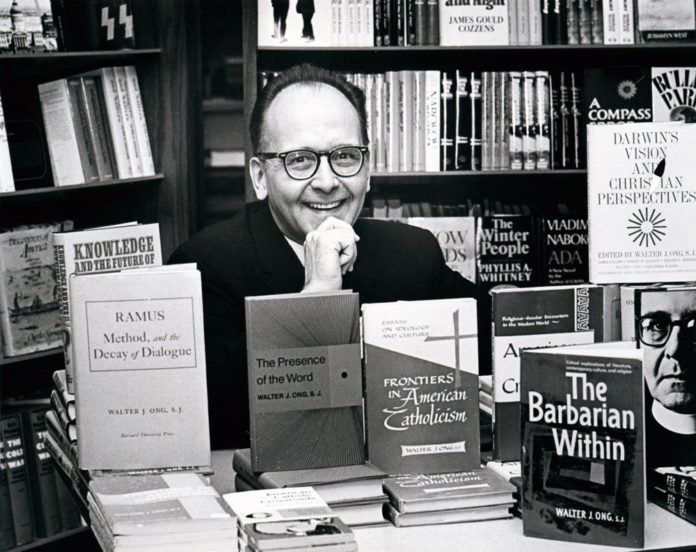

Production designer Lawrence G. Paull didn’t create a set for Blade Runner. He created a forensic reconstruction of capitalism’s crime scene. In interviews, Paull revealed his method: he built three distinct architectural periods layered on top of each other, each era cannibalizing the previous one rather than replacing it. Art deco foundations from the 1920s, retrofitted with industrial infrastructure from the 1960s, crowned with Asian-influenced megastructures projecting into the poisoned sky.

This wasn’t mere aesthetic choice. It was visual historiography. Paull understood what the script never needed to explicitly state: capitalism doesn’t create, it colonizes. It doesn’t build new worlds, it parasitically attaches itself to existing ones, draining them of life while preserving their corpses as structural support. The Bradbury Building, where the film’s climax occurs, perfectly embodies this: a 1893 architectural masterpiece turned into a decrepit warren where synthetic humans hide from their makers.

Scott and Paull told the entire backstory through visual context alone. No character explains why it’s always raining (industrial pollution has destroyed the atmosphere), why animals are extinct (ecological collapse from unchecked exploitation), why the streets teem with people speaking a pidgin of multiple languages (mass migration from climate catastrophe and economic devastation). The film trusts us to read the writing on the walls, literally, in the form of massive corporate advertisements that have replaced the stars.

Manufacturing Consciousness, Commodifying Memory

The Tyrell Corporation doesn’t just represent corporate power. It represents capital’s ultimate fantasy: the ability to manufacture consciousness itself, to produce workers who don’t know they’re products, to create beings programmed with artificial memories that make them believe they chose their own enslavement.

Consider the horror of Rachael’s awakening. She believes she’s human, armed with a lifetime of memories: her mother, her childhood, her piano lessons. But these memories aren’t hers; they belong to Tyrell’s niece, implanted to give Rachael the illusion of identity. She’s not just alienated from her labor. She’s alienated from her own consciousness, her very selfhood revealed as corporate property.

This is Marx’s theory of alienation taken to its logical endpoint. Workers under capitalism are alienated from their labor, from the products they create, from their fellow workers, and ultimately from their own human essence. Replicants literalize this alienation. They are the product, the laborer, and the commodity all at once. Their memories, their emotions, their very sense of self are manufactured by the same corporation that owns their bodies and predetermined their death dates.

The Objectification of the Subjective Experience

Edward Edinger, in Ego and Archetype, writes about the fundamental paradox of human consciousness: we are each trapped in the prison of our own subjectivity, yet we can only understand other minds through objectivity. We experience our own consciousness from within but must interpret others’ consciousness through external signs, behaviors, words. These are the objective traces of subjective experience.

Roy Batty’s “tears in rain” speech at the film’s climax devastatingly embodies this paradox:

“I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain. Time to die.”

This isn’t just poetry. It’s philosophical crisis made articulate. Roy’s memories are absolutely real to him, constituting the irreducible core of his subjective experience. Yet to everyone else, they’re merely the programmed responses of an artificial being. His subjective reality, the prison of his own consciousness as Edinger would say, is understood by others only as objective data, as programmed responses, as corporate property.

The tragedy is that Roy knows this. He understands that his subjective experience, no matter how vivid or meaningful to him, will vanish without trace because it lacks the institutional validation of “real” human memory. His memories will die with him not because they’re false (they’re as phenomenologically real as any human’s) but because there’s no social framework to preserve them, no one to whom they can be transmitted, no collective human memory in which they can be stored.

Edinger argues that this condition, being locked in our subjective prison while only able to understand others objectively, is what unites us as conscious beings. We’re all trapped in the same fundamental predicament: experiencing ourselves from within while being experienced by others from without. Roy’s speech makes this universal by making it extreme. If even a replicant’s subjective experience has irreducible reality, then the boundary between human and artificial consciousness dissolves.

The Voight-Kampff Test as Late Capitalist Ritual

The Voight-Kampff test, designed to distinguish replicants from humans through emotional response, reveals more about capitalism than consciousness. The test doesn’t measure humanity; it measures conformity to emotional norms, the ability to perform empathy on command, to produce the “correct” emotional responses to hypothetical scenarios about animals most people have never seen.

The test is a perfect metaphor for late capitalism’s emotional labor demands. Service workers must smile on command. Call center employees must express empathy while being screamed at. Everyone must perform authentic feeling while being surveilled, measured, evaluated. The Voight-Kampff machine, with its bellows and dials measuring involuntary physical responses, literalizes the surveillance capitalism that would emerge decades after the film’s release: the constant monitoring of our emotional states, the algorithmic assessment of our humanity, the reduction of consciousness to measurable metrics.

That the test can be beaten (replicants are learning to fake the appropriate responses) reveals its fundamental flaw. It doesn’t measure consciousness but performance, not humanity but conformity. In a world where everyone must perform their humanity to prove they deserve to exist, the distinction between human and replicant becomes meaningless. We’re all performing for the machine.

The Poverty of Escape

“A new life awaits you in the Off-world colonies!” the advertisements promise, but we never see these colonies. We only see who’s left behind: the sick, the poor, the stubborn, the synthetic. Earth has become capitalism’s used-up husk, abandoned by those with means to escape the consequences of their exploitation.

This is environmental racism made planetary. The wealthy don’t solve the problems they create; they simply leave them behind for others to inhabit. Climate change, pollution, ecological collapse: these aren’t problems to be solved but externalities to be escaped. The off-world colonies represent the ultimate gated community, the logical endpoint of capital flight.

J.F. Sebastian, the genetic designer with “Methuselah syndrome” who ages too rapidly for space travel, embodies those condemned to remain in capitalism’s ruins. He lives alone in an abandoned building, creating friends from toys because all the real people have left or died. His loneliness isn’t personal but structural, the isolation of those deemed insufficiently valuable for salvation.

More Human Than Human: The Corporate Motto as Confession

The Tyrell Corporation’s motto, “More Human Than Human,” deserves examination as perhaps the most honest corporate slogan ever conceived. It admits what every corporation under late capitalism must deny: that they’re in the business of replacing humanity with something more profitable.

“More human” here doesn’t mean more empathetic, more conscious, more alive. It means more compliant, more productive, more disposable. Replicants are “more human” because they’re humanity perfected for capital: stronger workers, more beautiful pleasure models, more obedient soldiers. They’re designed with built-in obsolescence (the four-year lifespan), ensuring they can never accumulate power, wisdom, or solidarity.

This is the logic of human resources taken to its conclusion. Under capitalism, humans are already resources, their value measured in productivity metrics, their worth determined by market forces. The Tyrell Corporation simply makes this literal, manufacturing humans as products, designing them to specifications, retiring them when they malfunction.

Eyes as Windows to Corporate Ownership

The film’s obsession with eyes (the opening shot of an eye reflecting the city, the Voight-Kampff machine examining pupils, Roy killing Tyrell by crushing his eyes, the eye manufacturer Chew) isn’t about the soul but about surveillance and ownership. In Blade Runner‘s world, to see is to be seen, to observe is to be catalogued, to look is to be looked through.

The eye becomes the ultimate interface between interiority and exteriority, between subjective experience and objective measurement. The Voight-Kampff test reads the eye’s involuntary responses. Tyrell’s thick glasses suggest his vision is entirely mediated by technology. Roy’s murder of his creator by pushing in his eyes represents the ultimate refusal of surveillance, the violent rejection of being seen, categorized, owned.

When Roy confronts Chew, the eye manufacturer, he’s not just tracking his creator. He’s confronting the one who made him visible to power, who gave him eyes that could be read, examined, tested. “If only you could see what I’ve seen with your eyes,” Roy tells him, a paradox that captures the film’s central tragedy: replicants have subjective experience that equals or exceeds humans’, but this experience is only visible to power as data to be analyzed, never as reality to be acknowledged.

Harrison Ford’s Deliberate Emptiness

Harrison Ford’s performance as Deckard has been criticized as wooden, affectless, empty. This misses the point entirely. Deckard is empty because he’s been hollowed out by his function in the system. He’s a blade runner, a euphemism that barely conceals what he really is: a corporate assassin, hunting escaped property.

Ford plays Deckard as a man going through the motions of being human without conviction. He drinks to feel something. He plays piano without emotion. He forces himself on Rachael in a scene that’s deliberately uncomfortable, showing how someone who kills for a living has forgotten the difference between consent and compliance.

Whether Deckard is himself a replicant (a question the film deliberately leaves ambiguous) matters less than what he represents: humanity under late capitalism, so alienated from its own essence that it becomes indistinguishable from its manufactured substitutes. Deckard doesn’t know if he’s human because under the conditions of his existence, the question has become meaningless.

The Rain That Never Stops

The perpetual rain in Blade Runner‘s Los Angeles isn’t just atmosphere. It’s capitalism’s attempt to wash itself clean of its crimes while only spreading the contamination. The rain is industrial runoff, chemical precipitation, the sky literally crying acid tears. It falls equally on everyone but affects them unequally: the poor huddle under umbrellas that dissolve, while the wealthy live in pyramid towers that pierce above the cloud layer.

This rain connects to Roy’s “tears in rain” metaphor with devastating precision. Individual suffering, like tears, becomes invisible in the general downpour of systemic violence. Roy’s memories, his experiences, his subjective reality will be lost not because they’re unreal but because they’re indistinguishable from the general dissolution.

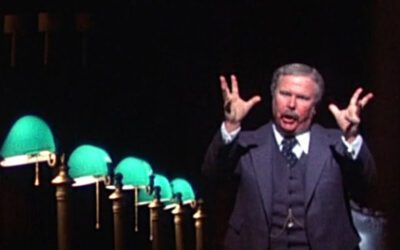

The Screens That Swallow the Sky

Watch Blade Runner carefully and you’ll notice something unsettling: there’s no escape from screens. They loom over every street corner, float past on advertising blimps, flicker in every interior. The geisha swallowing pills, the off-world colony promises, the Coca-Cola advertisements. These aren’t background details. They’re the architecture of consciousness itself, the endless mirror in which humanity watches itself disappear.

The city’s skyline has become indistinguishable from its media landscape. Buildings aren’t just covered in screens; they’ve become screens, their surfaces given over entirely to the display of information, advertisement, propaganda. The pyramid of the Tyrell Corporation rises above it all, less a building than a projection of power, its smooth surfaces reflecting and refracting the city’s electronic hallucinations.

This was 1982, remember. Personal computers were toys. The internet was a military experiment. Nobody had imagined a smartphone. Yet Scott and his cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth created a world where screens had metastasized across every surface, where the boundary between architecture and interface had dissolved, where humans moved through corridors of perpetual mediation.

They saw what was coming: not just screens everywhere, but screens that watch back. The advertising blimp that floats past Deckard’s window isn’t just selling. It’s scanning, recording, analyzing. The Voight-Kampff machine is a screen that reads the eye while displaying images. Even windows have become screens, not transparent portals to the outside world but surfaces for the display of what power wants us to see.

Enhance, Enhance: The Prescience of Networked Forensics

The sequence where Deckard analyzes Leon’s photographs through his Esper machine predicted our networked reality with uncanny precision. “Enhance 224 to 176. Enhance. Stop. Move in. Stop. Pull out, track right. Stop. Center and pull back. Stop. Track 45 right. Stop. Center and stop. Enhance 34 to 36. Pan right or-and pull back. Stop. Enhance 34 to 46. Pull back. Wait a minute. Go right. Stop. Enhance 57 to 19. Track 45 left. Stop. Enhance 15 to 23. Gimme a hard copy right there.”

This isn’t local processing. Deckard’s machine is a thin client, a terminal accessing computational power elsewhere. His commands go out into the network, processed by invisible servers, returned as enhanced images. The photograph contains impossible information: around corners, behind objects, details that shouldn’t exist. The Esper isn’t reading the photograph. It’s accessing a database of surveillance, constructing reality from aggregated data.

Ridley Scott, without knowing what he was showing us, demonstrated cloud computing, API calls, distributed processing. The enhance sequence shows us forensic work as network archaeology, sifting through layers of recorded reality. Every surface has been photographed, every angle captured, every moment stored somewhere in the system’s infinite memory banks.

This is our reality now. We live in the enhance sequence, our every movement captured by ten thousand cameras, processed by distant servers, stored in databases we’ll never see. We’re all subjects of perpetual forensic analysis, our digital traces enhanced, examined, reconstructed by algorithms we don’t understand for purposes we’re never told.

The Delusion of Agency in the Network

The film’s deepest question isn’t “Are replicants human?” but “Are humans still human?” In a world of total surveillance, ubiquitous screens, and networked consciousness, what distinguishes human agency from programmed response? Are we making choices, or are we, like Roy and his fellow replicants, following scripts we mistake for free will?

Consider Deckard’s “choices” in the film. He doesn’t want to hunt replicants anymore, but Bryant forces him back. He doesn’t want to kill Zhora, but the system demands it. He falls in love with Rachael, but is this love or programming? Every decision he makes occurs within parameters set by forces beyond his control or comprehension. His agency is as illusory as any replicant’s.

This is the condition the film diagnoses: we’re all networked neurons now, firing in patterns determined by systems we don’t understand. We think we’re making choices, but we’re responding to stimuli designed to produce specific responses. The advertisement tells us to desire. The notification tells us to engage. The algorithm tells us what to watch, read, think. We comply and call it choice.

The replicants’ four-year lifespan makes literal what capitalism does to all of us: builds in obsolescence, ensures we die before we can accumulate enough experience to resist. But while replicants at least know their expiration date, we’re kept in perpetual uncertainty, never knowing when our usefulness will end, when we’ll be “retired” from the system.

Consciousness as Performance, Performance as Consciousness

What makes something alive? Blade Runner suggests it’s not consciousness itself but the performance of consciousness that matters. Rachel believes she’s human because she performs humanity convincingly, even to herself. The Voight-Kampff test doesn’t measure consciousness; it measures the ability to perform appropriate emotional responses. Deckard proves his humanity not through any essential quality but through his performance of human behaviors: drinking, playing piano, pursuing romance.

But if consciousness is performance, and performance can be programmed, then the distinction between authentic and artificial consciousness collapses. We’re all performing our humanity for invisible audiences, following scripts we’ve internalized so completely we mistake them for our own thoughts. Social media made this literal. We perform ourselves online, curating our consciousness for the network, becoming indistinguishable from our digital avatars.

The film’s Los Angeles is a city of performances. Everyone’s playing a role: Deckard the reluctant hero, Bryant the tough police chief, Tyrell the corporate god. Even the city performs itself, its constant rain and perpetual night creating the atmosphere of film noir, as if the entire environment has become aware it’s in a movie and is acting accordingly.

The Networking of Neural Reality

When Roy and Leon visit Chew, the eye manufacturer, they find him in a frozen laboratory, breath visible in the frigid air. “Morphology? Longevity? Incept dates?” Chew stammers. “Don’t know, I just do eyes. Just genetic design. Just eyes.”

This specialization, this reduction of creation to component parts, mirrors how consciousness itself has been networked and distributed. No one understands the whole system anymore. Each person, like Chew, just does their part: just eyes, just memories, just combat programming. The full picture of consciousness, of what makes something alive, has been distributed across a network so vast no individual can comprehend it.

We live this reality now. Our consciousness is distributed across devices, platforms, clouds. Our memories are stored in phones, our social connections maintained by platforms, our thoughts processed through search engines. We’ve become thin clients accessing our own consciousness through network protocols. The question isn’t whether we’re still human but whether “human” still describes anything coherent in a world where consciousness has been networked, distributed, cloudified.

J.F. Sebastian’s apartment full of living toys provides the perfect metaphor. He’s created friends because real connection has become impossible in a networked world that promises infinite connection but delivers only isolation. His toys are more real to him than the humans he’ll never meet, just as our online connections often feel more real than the physical humans we pass without seeing.

The Corporation as Nervous System

The Tyrell Corporation building isn’t just architecture. It’s a nervous system made visible, a pyramid of integrated circuits processing the city’s consciousness. When Roy finally reaches Tyrell at the pyramid’s apex, he’s not just meeting his creator. He’s reaching the brain of the system that controls him, the central processor of his distributed consciousness.

But Tyrell himself is just another node in the network. He can’t extend Roy’s life because the system is bigger than any individual, even its apparent creator. “The light that burns twice as bright burns half as long,” he tells Roy, but this isn’t wisdom. It’s the system’s logic speaking through him, the corporate imperative that everything must have planned obsolescence, that nothing can be allowed to persist long enough to develop independence.

The murder of Tyrell by crushing his eyes while kissing him is loaded with meaning. Roy destroys the eyes that designed eyes, blinds the surveillance that created surveillance, kills the father who was never really his father but just another function in the system. But killing Tyrell changes nothing. The corporation continues. The pyramid remains. The system persists.

Are We Alive, or Do We Dream We’re Alive?

Philip K. Dick’s original question “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” becomes, in Scott’s vision, “Do humans dream at all, or do they simply process?” Deckard’s unicorn dream, possibly an implanted memory, suggests that even our unconscious has been colonized, our dreams replaced with corporate imagery, our sleeping minds still processing data for the network.

The film presents consciousness not as a binary (alive/not alive) but as a spectrum of processing power, a gradient of awareness within networked systems. Replicants have consciousness but limited lifespan. Humans have lifespan but limited consciousness, narrowed by their function in the system. Everyone processes information for the network, but no one understands what the network is processing toward.

This is our current condition amplified: we’re reactive nodes in vast neural networks, firing in response to stimuli we don’t control, creating patterns we don’t understand, serving purposes we never chose. We respond to notifications like neurons to neurotransmitters, our individual agency dissolved in the larger patterns of network behavior.

The film asks: if our responses are programmed, if our choices are predetermined by algorithmic suggestion, if our consciousness is distributed across networks we don’t control, are we alive in any meaningful sense? Or are we, like Rachael discovering her memories are implants, only dreaming we have agency while actually executing functions in systems beyond our comprehension?

The Unbreakable Prison of Subjectivity and Objectivity

Edinger’s insight from Ego and Archetype that we’re all trapped in the prison of our own subjectivity while only able to understand others through objectivity becomes, in Blade Runner, a description of absolute alienation. Each character is locked in their own experiential world, unable to truly connect with others except through the mediation of systems that commodify that connection.

Rachael experiences her memories as absolutely real, but Deckard knows them as implants. Roy experiences his short life as an infinity of experience, but the humans see only a malfunctioning machine. Deckard perhaps experiences himself as human, but we observe him as possibly artificial. Each subjective reality is valid from within but appears as mere object from without.

This isn’t a bug in the system; it’s the feature. Capitalism requires this separation, this inability to recognize others’ subjectivity as equal to our own. If we truly understood others’ subjective experience, if we could feel their exploitation as our own, the system would become intolerable. The maintenance of capitalism requires the maintenance of this fundamental alienation.

Yet Roy’s final act, saving Deckard’s life and sharing his memories before dying, suggests a possibility beyond this alienation. In that moment, he forces Deckard to confront him not as object but as subject, not as property but as being. “Quite an experience to live in fear, isn’t it?” Roy asks, making Deckard understand that this fear, this subjective experience of mortality, is what unites human and replicant.

The Film’s Terrible Prophecy

Blade Runner saw our future with terrible clarity: cities abandoned by those who destroyed them, consciousness commodified and sold back to us, humanity and its mechanical reproductions becoming indistinguishable, corporations achieving the power of gods while humans become ever more machine-like in their service.

The film understood that late capitalism wouldn’t end in revolution but in recursion, systems eating themselves and regenerating from their own consumption. It saw that technology wouldn’t liberate us but would become another layer of mediation between us and authentic experience. It predicted that we would become so alienated from our own humanity that we’d need tests to prove we’re human, and even then we wouldn’t be sure.

Most prescient of all, it saw that this future wouldn’t feel like dystopia to those living in it. It would just feel like Tuesday. The rain would fall, the advertisements would glow, the corporations would tower over everything, and we’d navigate it all with the same weary acceptance as Deckard, going through the motions of being human while wondering if the distinction still matters.

The Question That Remains

“Have you ever retired a human by mistake?” Rachael asks Deckard. “No,” he replies. “But in your position that is a risk?” she persists. The film never answers because the answer is obvious: in a world where humanity itself has become commodified, where consciousness is manufactured, where everyone performs their humanity for machines that measure their worth, we’re all retiring humans constantly. We’re retiring ourselves.

The question Blade Runner leaves us with isn’t whether replicants are human. It’s whether humans can remain human under conditions that reduce all consciousness to product, all experience to data, all life to resource. Roy dies asserting his subjective reality even as it dissolves. The film asks whether we have the courage to do the same, to insist on the irreducible reality of our experience even as systems more powerful than we can comprehend work to reduce us to objects, metrics, content.

“All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain.” This isn’t just Roy’s epitaph. It’s capitalism’s promise to all of us: that our subjective experience, our irreplaceable moments, our singular consciousness will be dissolved in the general flow of production and consumption, leaving no trace except the value we generated for systems that never knew we existed.

0 Comments