Who Was June Singer?

June Singer (1920-2004) was a renowned Jungian analyst, author, and educator who made significant contributions to the development of analytical psychology. Her work focused on exploring the creative potential of the unconscious and integrating Jungian concepts with other fields such as art, literature, and feminism. Singer’s innovative approach emphasized the transformative power of symbols, myths, and imagination in the individuation process.

Main Ideas and Key Points:

- June Singer’s work focuses on the creative unconscious – the deep source of symbols, archetypes, and instinctual energies that shape our psychic life.

- Singer emphasizes the importance of engaging with the unconscious through dreams, active imagination, art, and creative expression as a means of psychological growth and individuation.

- She explores the role of gender archetypes – the anima and animus – in shaping our relationships, creativity, and spiritual development.

- Singer sees the Self archetype as the guiding center of the individuation process, reflected in our personal and cultural God-images.

- Art and imagination are central to Singer’s approach, as powerful ways to access the unconscious, express its wisdom, and engage in sacred co-creation.

- Singer was a pioneer in dream work and active imagination, developing innovative methods for exploring the inner world.

- She worked to bring feminine perspectives into depth psychology, challenging patriarchal assumptions and honoring the archetype of the Great Mother.

- Singer believed depth psychology could support social and cultural transformation by making the collective unconscious conscious and healing splits in the psyche.

- Her legacy expands the boundaries of Jungian thought and inspires contemporary seekers with a vision of a symbolic, creative, and whole-making life.

- In an age of disconnection and fragmentation, Singer’s call to engage the unconscious and birth a new psychology of meaning is more relevant than ever.

The Creative Unconscious and Symbolic Life 1.1 The Nature of the Unconscious

In her seminal work, Boundaries of the Soul: The Practice of Jung’s Psychology (1972), Singer delves into the nature and dynamics of the unconscious mind. Drawing on Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious, she describes it as a vast, creative matrix that transcends individual experience. The unconscious, Singer argues, is not merely a repository of repressed memories and instinctual drives, but a living, self-regulating system that seeks to express itself through symbols, dreams, and synchronicities.

For Singer, the contents of the unconscious are not random or meaningless, but imbued with a deep, teleological significance. They represent the psyche’s innate drive towards wholeness and self-realization – a process Jung called individuation. By engaging with the symbolic messages of the unconscious, Singer believes, we can align ourselves with this transformative impulse and discover our unique path in life.

1 Symbolic Life and Mythic Imagination

In Seeing Through the Visible World: Jung, Gnosis, and Chaos (1990), Singer explores the importance of cultivating a symbolic approach to life. In a world that prizes literal, rational modes of thought, she argues, we have lost touch with the mythic dimension of existence – the realm of metaphor, imagination, and poetic truth. This has led to a flattening of our experience and a sense of alienation from the deeper currents of the psyche.

To redress this imbalance, Singer calls for a revival of what she terms “symbolic life” – a way of engaging with the world that is attuned to archetypal patterns, correspondences, and hidden meanings. By immersing ourselves in the language of myth, fairytale, and sacred story, she suggests, we can reawaken our capacity for wonder, mystery, and numinous experience. We can begin to see through the visible world to the archetypal realities that underlie it.

This symbolic sensibility, Singer argues, is not a regression to primitive superstition, but a higher mode of cognition that integrates the conscious and unconscious mind. It allows us to apprehend the world in its full depth and complexity, revealing the interdependence of matter and psyche, nature and spirit. By cultivating symbolic life, we open ourselves to the creative, transformative power of the unconscious and align ourselves with the mythic imagination of the soul.

Archetypes and the Individuation Process

The Anima and Animus

In The Unholy Bible: A Psychological Interpretation of William Blake (1970) and Androgyny: Toward a New Theory of Sexuality (1976), Singer examines the role of gender archetypes in the psyche. She sees the anima (the inner feminine in the male) and animus (the inner masculine in the female) as critical components of psychological development, mediating between the conscious ego and the unconscious Self.

For Singer, the anima and animus are not merely cultural stereotypes or biological imperatives, but archetypal energies that transcend individual experience. They represent the psyche’s inherent androgyny – its capacity to integrate and transcend opposites. By engaging with these contrasexual energies, Singer argues, we can overcome the limitations of gender roles and express the full range of our human potential.

This process, however, is often fraught with tension and conflict. In a patriarchal society, Singer observes, the feminine is often devalued or repressed, both in men and women. This leads to a distortion of the anima/animus dynamic, as the ego identifies with one-sided masculine or feminine traits. To heal this split, Singer calls for a revaluation of the feminine and a integration of gender polarities within the psyche.

Ultimately, Singer sees the anima and animus as guides on the path of individuation – the lifelong journey towards wholeness and self-realization. As we engage with these archetypes consciously, they lead us beyond narrow ego identifications and connect us with the deeper ground of our being. They challenge us to embrace our contrasexual qualities, to balance the receptive and active, the rational and imaginal aspects of the psyche. In this way, the anima and animus play a crucial role in birthing the Self – the central archetype of psychic wholeness.

The Self and the God-Image

In The Gnostic Jung and the Seven Sermons to the Dead (1982), Singer explores Jung’s concept of the Self – the archetype of psychic totality that guides the individuation process. For Jung, the Self is not the ego, but the supreme psychic authority, the “God within” that orchestrates our psychological development. It is experienced as a transpersonal center, a source of meaning, wisdom and spiritual connection that transcends the individual.

Singer delves into the ways in which the Self is represented in different religious and mystical traditions. She sees Christ, Buddha, Atman, the Philosopher’s Stone, and other numinous symbols as expressions of the Self archetype – personifications of the divine human potential. These God-images, Singer argues, are not mere projections or wish-fulfillments, but autonomous realities that have a life of their own. They are the face of the Self as it appears to the conscious mind.

For Singer, the individuation process is essentially a religious quest – a journey to discover and incarnate the Self in one’s life. This involves a confrontation with the unconscious, a descent into the depths of the psyche where the ego is stripped of its illusions and pretensions. In this “dark night of the soul,” the old identity dies and a new, more authentic self is born – one that is aligned with the deeper wisdom of the psyche.

This process, Singer acknowledges, is not for the faint of heart. It requires a willingness to surrender control, to let go of attachment to the known and venture into the unknown. It demands a radical trust in the intelligence of the unconscious, a faith that the dissolution of the ego will lead to a greater wholeness. Yet for those who embark on this journey, the rewards are immense: a life imbued with meaning, purpose, and an abiding connection to the sacred.

Creativity, Art and Imagination

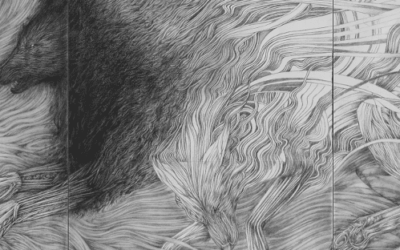

In Blake, Jung, and the Collective Unconscious: The Conflict Between Reason and Imagination (1990), Singer examines the role of creativity and imagination in the individuation process. She sees artistic expression as a vital means of engaging with the unconscious, giving form to its archetypal contents and integrating them into conscious awareness.

For Singer, the creative process is not merely a matter of self-expression, but a dialogue with the deeper layers of the psyche. The artist, in a sense, is a medium – a channel for the unconscious to communicate its wisdom and guidance. By surrendering to the creative impulse, the ego allows itself to be moved and transformed by forces greater than itself.

This process, Singer argues, is epitomized in the work of visionary artists like William Blake. Blake’s poetry and engravings, she suggests, are not mere literary or aesthetic artifacts, but direct expressions of archetypal reality. They are windows into the collective unconscious, revealing the mythic dimensions of the psyche in all their numinous power.

Singer sees Blake as a model for the kind of creative engagement she advocates. Rather than retreating into solipsistic fantasy, Blake used his imagination to probe the depths of the human condition, to give voice to the archetypal energies that shape our lives. His art was a form of active imagination – a way of dialoguing with the unconscious and bringing its contents into conscious awareness.

For Singer, this kind of imaginative engagement is essential for psychological growth and transformation. By cultivating our capacity for symbolic thought and expression, we open ourselves to the guidance of the unconscious. We tap into the wellsprings of creativity that lie within us, aligning ourselves with the regenerative powers of the psyche.

This is not a purely individual process, but one that has collective implications. In a world that is increasingly dominated by literal, rational modes of thought, Singer sees imagination as a subversive force – a means of challenging the status quo and envisioning new possibilities. By nurturing our imaginative capacities, we not only heal ourselves, but contribute to the transformation of culture and society.

Dreams and Active Imagination

In The Unholy Bible: Blake, Jung, and the Collective Unconscious (2000), Singer explores the transformative potential of dreams and active imagination. She sees these as essential tools for engaging with the unconscious, accessing its wisdom and integrating its contents into conscious awareness.

For Singer, dreams are not merely random neurological events, but meaningful communications from the deeper layers of the psyche. They speak in the language of symbol and metaphor, revealing the archetypal patterns that shape our lives. By attending to our dreams and working to understand their significance, we open a direct channel to the unconscious.

Singer was a pioneer in the use of group dream work as a means of amplifying and exploring dream imagery. In her workshops and seminars, participants would share their dreams and associate to each other’s material, teasing out the collective themes and patterns. This process, she found, not only deepened individual insight, but fostered a sense of community and shared purpose among participants.

Singer was also a strong advocate of active imagination – a technique developed by Jung for dialoguing with the unconscious. In active imagination, the dreamer engages with the images and figures that appear in dreams or fantasies, allowing them to speak and interact autonomously. This can take the form of visualization, automatic writing, or artistic expression.

For Singer, active imagination is a powerful tool for bridging the gap between the conscious and unconscious mind. By engaging the dream figures in dialogue, we can access the deeper layers of the psyche and bring their wisdom into conscious awareness. We can confront our shadows, integrate our animas/animus, and align ourselves with the guidance of the Self.

This process, Singer emphasizes, requires a willingness to surrender control and trust in the intelligence of the unconscious. It demands a kind of radical openness, a readiness to venture into unknown territory and be transformed by what we encounter there. Yet for those who take up this practice, the rewards are immense: a deepened sense of meaning, purpose, and connection to the greater whole.

The Feminine in Depth Psychology

In The Feminine in Jungian Psychology and in Christian Theology (1986) and Energies and Patterns in Psychological Type: The Reservoir of Consciousness (1992), Singer explores the role of the feminine in depth psychology and spirituality. She was a passionate advocate for bringing feminine perspectives into the largely male-dominated field of psychoanalysis, challenging its patriarchal assumptions and biases.

For Singer, the repression and devaluation of the feminine was not merely a political or social issue, but a profound psychic wound that affected all of humanity. In a culture that privileged masculine qualities of rationality, independence, and assertiveness, the feminine values of receptivity, relatedness, and intuition were often dismissed or pathologized. This, she argued, created a dangerous imbalance in the psyche, both individually and collectively.

To redress this imbalance, Singer called for a revaluation of the feminine and a recovery of its sacred dimensions. She saw the Great Mother archetype as a primal source of life, creativity, and spiritual nourishment that had been repressed by patriarchal culture. By reconnecting with this archetype, both men and women could heal the split between spirit and nature, mind and body, self and other.

Singer was particularly interested in the ways in which the feminine manifested in religious experience. She noted that while masculine images of God as a supreme ruler or lawgiver were dominant in the Judeo-Christian tradition, there were also powerful feminine symbols of the divine – the Shekinah in Judaism, the Holy Spirit in Christianity, the various goddesses of pagan traditions. These images, she argued, pointed to a more inclusive, relational understanding of the sacred.

For Singer, embracing the feminine did not mean rejecting the masculine, but rather integrating and balancing these complementary energies. She envisioned a new model of psychological and spiritual development that honored both the agency and communion, the independence and interdependence of the self. This required a radical rethinking of traditional gender roles and a willingness to embrace the full spectrum of human qualities.

Ultimately, Singer believed that the recovery of the feminine was essential not only for individual healing, but for the transformation of society. In a world torn apart by violence, domination, and ecological destruction, she saw the feminine values of care, compassion, and reverence for life as crucial for our collective survival. By honoring the feminine within and without, we could begin to create a more just, sustainable, and life-affirming world.

Jungian Psychology and Social Change

In Culture and the Collective Unconscious (1982) and Modern Woman in Search of Soul (1988), Singer explores the social and political implications of Jungian psychology. While Jung himself was often criticized for his apolitical stance and focus on individual development, Singer argued that depth psychology had a vital role to play in social and cultural transformation.

For Singer, the crises of the modern world – war, oppression, environmental degradation – were not merely political or economic problems, but manifestations of a deeper psychic imbalance. They reflected the shadow side of the collective psyche, the unintegrated archetypal energies that were erupting in destructive ways. To address these crises, Singer believed, we needed to confront the collective unconscious and work to integrate its contents.

This meant, first and foremost, acknowledging the reality of the psyche as a powerful force in human affairs. It meant recognizing that beneath the surface of rational discourse and pragmatic concerns, there were deeper currents of meaning, myth, and emotion that shaped our individual and collective behavior. By making these unconscious factors conscious, we could begin to work with them in a more intentional and responsible way.

Singer was particularly concerned with issues of gender, race, and power in depth psychology and society at large. She challenged the patriarchal assumptions of traditional Freudian and Jungian thought, which often relegated women to secondary or stereotypical roles. She called for a more inclusive and diverse approach to psychoanalysis, one that honored the experiences and perspectives of marginalized groups.

At the same time, Singer recognized that the path to social change was not simply a matter of political activism or ideological commitment. It required a deep, personal transformation – a willingness to confront one’s own shadows, biases, and complicity in systems of oppression. Only by doing this inner work, she believed, could we hope to create authentic and lasting change in the world.

For Singer, this inner work was inherently connected to the outer work of social justice and ecological responsibility. By individuating – by becoming more whole, conscious, and compassionate individuals – we could begin to create a more whole, conscious, and compassionate society. We could move beyond the polarities of us vs. them, good vs. evil, and work towards a more inclusive vision of the human community.

Ultimately, Singer envisioned a world in which the insights of depth psychology would be applied not only in the consulting room, but in the public square. She dreamed of a new kind of politics, one that was informed by an understanding of the archetypal dimensions of human experience. This would be a politics of the soul, a way of engaging with the world that honored the full complexity and potential of the human psyche.

Legacy and Influence

June Singer’s work has had a profound and enduring impact on the field of analytical psychology and beyond. Her books and lectures have inspired generations of therapists, artists, activists, and spiritual seekers, offering a vision of depth psychology that is at once personal and political, individual and collective.

One of Singer’s most significant contributions was to bring a feminist perspective to Jungian thought. By challenging the patriarchal assumptions of traditional psychoanalysis and advocating for a revaluation of the feminine, she helped to pave the way for a more inclusive and diverse approach to depth psychology. Her work has been particularly influential in the development of feminist archetypal theory, which explores the ways in which gender roles and identities are shaped by archetypal patterns.

Singer’s emphasis on the creative and transformative power of the unconscious has also had a major impact on the fields of art, literature, and spirituality. Her insights into the role of symbolic experience and mythic imagination have inspired countless artists and writers to explore the archetypal dimensions of their work. Her vision of a symbolic life, one that is attuned to the numinous and the transcendent, has resonated with seekers from diverse spiritual traditions.

Perhaps most importantly, Singer’s work has helped to bridge the gap between depth psychology and social activism. By illuminating the ways in which personal and collective shadow material contributes to systems of oppression and injustice, she has called us to a deeper engagement with the world. Her vision of a politics of the soul, one that is grounded in an understanding of the archetypal forces that shape human experience, remains a powerful inspiration for those seeking to create a more just and compassionate society.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Jungian Analysts

0 Comments