The Archetypal Psychology of Steven Mithen: Exploring the Evolution of the Mind

Who is Steven Mithen?

Steven Mithen is a leading British archaeologist and anthropologist whose work has revolutionized our understanding of the evolution of the human mind. Drawing on a wide range of disciplines, from cognitive neuroscience to comparative mythology, Mithen has developed a comprehensive framework for understanding how our unique cognitive capacities emerged over the course of evolutionary history.

Central to Mithen’s approach is the concept of cognitive fluidity – the ability to make connections across different domains of knowledge and experience. According to Mithen, this capacity for flexible and integrative thinking is what sets us apart from other species and enables us to engage in the complex symbolic and cultural practices that define human existence.

In this article, we will explore the key ideas and themes of Mithen’s work, from his early research on the origins of agriculture to his more recent investigations into the role of music and ritual in human evolution. We will examine how his insights have challenged conventional views of the mind and opened up new avenues for understanding the deep roots of human cognition and culture.

The Prehistory of the Mind

Mithen’s first major work, The Prehistory of the Mind (1996), laid the foundation for his subsequent explorations of human cognitive evolution. In this groundbreaking book, Mithen argues that the key to understanding the emergence of the modern human mind lies in the archaeological record of our early ancestors.

Drawing on a wealth of evidence from fossil remains, stone tools, and other artifacts, Mithen traces the development of human cognition from the earliest hominids to the rise of modern Homo sapiens. He proposes that this evolution was marked by a series of major transitions, each of which involved the integration of previously separate cognitive domains.

The first of these transitions, according to Mithen, occurred around 1.8 million years ago with the emergence of Homo erectus. This species, he argues, developed a new kind of “general intelligence” that allowed them to coordinate their technical and social skills in ways that earlier hominids could not. Evidence for this can be seen in the more complex stone tools and larger social groups of Homo erectus, which suggest a greater capacity for planning, cooperation, and communication.

The second major transition, Mithen proposes, took place around 500,000 years ago with the advent of archaic Homo sapiens. This period saw the emergence of new forms of symbolic expression, such as the use of pigments and the creation of decorative objects. For Mithen, these developments reflect a growing ability to represent and manipulate abstract concepts, which laid the foundation for the later emergence of language and art.

The final and most significant transition, according to Mithen, occurred in the Middle-Upper Paleolithic period, between 60,000 and 30,000 years ago. This was the time when modern Homo sapiens first appeared on the scene, and it was marked by an explosion of cultural and technological innovation. Cave paintings, decorative objects, and musical instruments all made their debut during this period, as did new forms of social organization and religious practice.

For Mithen, these developments reflect a fundamental shift in the way the human mind works. Rather than being limited to narrow domains of knowledge and skill, the modern human mind is characterized by a fluid and flexible intelligence that can make connections across different spheres of experience. This cognitive fluidity, he argues, is what enables us to engage in the kind of symbolic and imaginative thinking that underlies art, science, and religion.

The Role of Language and Metaphor

In The Prehistory of the Mind, Mithen also explores the role of language and metaphor in the emergence of human cognition. He argues that the evolution of language was a crucial step in the development of cognitive fluidity, as it provided a powerful tool for representing and manipulating abstract concepts.

According to Mithen, the origins of language can be traced back to the social grooming behaviors of early hominids. Just as primates use grooming to maintain social bonds and communicate emotional states, early humans may have used simple vocalizations and gestures to coordinate their activities and express their feelings. Over time, these proto-linguistic behaviors became more complex and systematic, eventually giving rise to the fully-fledged language abilities of modern humans.

One of the key features of language, Mithen argues, is its use of metaphor. By mapping familiar concepts onto unfamiliar domains, metaphors allow us to make sense of new experiences and ideas in terms of what we already know. For example, when we say that someone is “in the doghouse,” we are using a spatial metaphor to convey a social and emotional meaning.

Mithen sees evidence of metaphorical thinking in the earliest forms of human art and symbolism. The therianthropic figures of Upper Paleolithic cave paintings, which blend human and animal features, reflect a cognitive ability to merge different conceptual domains. Similarly, the widespread use of color symbolism in ancient art and ritual suggests a capacity for associative thinking that goes beyond literal representation.

For Mithen, the emergence of language and metaphor was a key driver of human cognitive evolution. By providing a means of representing and manipulating abstract concepts, language opened up new possibilities for symbolic thought and social coordination. And by enabling the creation of complex webs of meaning and association, metaphor laid the foundation for the rich cultural and imaginative lives of modern humans.

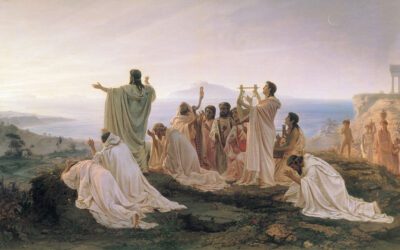

Music, Ritual, and Social Bonding

In his later work, particularly The Singing Neanderthals (2005), Mithen has explored the role of music and ritual in human evolution. Drawing on a range of archaeological, ethnographic, and psychological evidence, he argues that musical and ritual behaviors played a crucial role in the emergence of human sociality and culture.

According to Mithen, the origins of music can be traced back to the rhythmic vocalizations and body movements of early hominids. Just as many species of birds and mammals use rhythmic sounds and displays to attract mates and establish social bonds, early humans may have used similar behaviors to coordinate their activities and express their emotions.

Over time, these proto-musical behaviors became more elaborate and formalized, eventually giving rise to the complex musical traditions of modern human cultures. Mithen points to the discovery of bone flutes and other musical instruments in Upper Paleolithic sites as evidence of the antiquity and importance of music in human history.

But music, Mithen argues, is more than just a form of entertainment or self-expression. It also plays a crucial role in social bonding and group cohesion. By synchronizing their movements and vocalizations, people can create a powerful sense of unity and shared identity. This is why music and dance are such ubiquitous features of human social life, from religious rituals to political rallies to sporting events.

Mithen sees a similar function in the evolution of ritual behavior. Like music, ritual provides a means of coordinating social action and expressing shared emotions and beliefs. By engaging in ritualized behaviors, such as communal feasting or ceremonial gift-giving, people can reinforce their social ties and establish a sense of common purpose.

Moreover, Mithen argues, ritual serves as a kind of “social technology” that enables people to navigate complex social relationships and negotiate potential conflicts. By providing a structured framework for interaction and communication, ritual helps to maintain social order and promote cooperation.

For Mithen, the evolution of music and ritual was intimately connected to the emergence of human culture and sociality. By enabling new forms of social bonding and communication, these behaviors laid the foundation for the complex social and cultural lives of modern humans. And by shaping the way we think and feel about ourselves and others, they continue to play a crucial role in human experience and identity.

Archetypal Thought and Human Universals

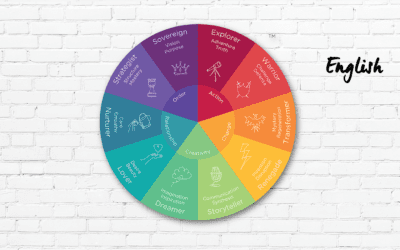

In his more recent work, Mithen has begun to explore the role of archetypal thought patterns in human cognition and culture. Drawing on the ideas of Carl Jung and other depth psychologists, he argues that certain basic cognitive templates or schemas recur across different cultures and historical periods, suggesting a common underlying structure to the human mind.

One of the most fundamental of these archetypal patterns, according to Mithen, is the distinction between self and other. From an early age, humans are able to distinguish between their own bodies and minds and those of other people and objects. This basic sense of self-other differentiation, Mithen argues, is what enables us to engage in social interaction and communication.

Another key archetype is the concept of agency or intentionality. Humans are naturally inclined to attribute goals, desires, and beliefs to other people and even to inanimate objects and natural phenomena. This tendency, known as “theory of mind,” is what allows us to understand and predict the behavior of others and to engage in complex social relationships.

Mithen also points to the prevalence of binary oppositions in human thought, such as male/female, good/evil, and life/death. These basic conceptual categories, he argues, provide a framework for making sense of the world and organizing our experiences. They are reflected in the myths, folktales, and religious beliefs of cultures around the world, suggesting a common cognitive substrate.

For Mithen, the existence of these archetypal thought patterns is evidence of the deep structure of the human mind. While the content of our thoughts and beliefs may vary across cultures and individuals, the basic cognitive templates that shape them are remarkably consistent. This suggests that the human mind is not a blank slate, but rather comes equipped with certain innate predispositions and capacities.

At the same time, Mithen is careful to point out that these archetypes are not fixed or deterministic. They are better understood as flexible resources that can be adapted to different cultural and historical contexts. The way in which a particular archetype is expressed or interpreted may vary widely across time and space, reflecting the diverse ways in which humans make sense of their experiences.

Mithen’s work on archetypal thought has important implications for our understanding of human universals and cultural diversity. By identifying the common cognitive patterns that underlie human thought and behavior, he helps to explain why certain themes and motifs recur across different cultures. At the same time, by emphasizing the flexibility and adaptability of these patterns, he allows for the immense diversity of human cultural expressions.

The Cognitive Foundations of Religion

One of the most intriguing applications of Mithen’s ideas is in the study of religion. In his book The Singing Neanderthals, Mithen argues that the cognitive capacities that underlie musical and ritual behavior may also have played a key role in the emergence of religious belief and practice.

According to Mithen, religion is a natural byproduct of the human mind’s tendency to attribute agency and intentionality to the world around us. Just as we are inclined to see other people as having minds and desires of their own, we may also be predisposed to see natural phenomena and abstract concepts as being animated by supernatural agents or forces.

This tendency, known as “hypersensitive agency detection,” may have evolved as a way of helping early humans avoid predators and other threats. By erring on the side of assuming that a rustle in the bushes or a shadow on the wall might be a lurking danger, our ancestors were more likely to survive and pass on their genes.

Over time, however, this cognitive bias may have been co-opted for other purposes, such as explaining the mysteries of the natural world and coping with the challenges of social life. By attributing events and experiences to the actions of supernatural agents, humans could make sense of the unpredictable and uncontrollable aspects of their lives and find comfort and meaning in the face of suffering and uncertainty.

Mithen sees evidence of this process in the earliest forms of religious art and symbolism. The animal-human hybrid figures of Upper Paleolithic cave paintings, for example, may reflect a belief in the existence of supernatural beings who could cross the boundaries between the human and animal worlds. Similarly, the elaborate burial practices of early humans suggest a belief in an afterlife and a concern for the fate of the soul.

For Mithen, the evolution of religion was closely intertwined with the emergence of human culture and sociality. By providing a shared framework of beliefs and practices, religion helped to bind people together into cohesive social groups and to coordinate their actions and intentions. At the same time, by offering a sense of meaning and purpose in the face of the unknown, religion helped to alleviate the existential anxieties that come with being human.

Implications and Applications

Mithen’s work has important implications for a wide range of fields, from psychology and anthropology to education and social policy. By providing a comprehensive framework for understanding the evolution and structure of the human mind, he opens up new avenues for research and application.

One key implication of Mithen’s work is the importance of integrating insights from different disciplines. By drawing on evidence from archaeology, anthropology, psychology, and neuroscience, Mithen is able to paint a more complete picture of human cognitive evolution than any one field could provide on its own. This interdisciplinary approach is crucial for understanding the complex interplay of biological, social, and cultural factors that shape human thought and behavior.

Another implication of Mithen’s work is the need to take seriously the role of non-verbal forms of communication and expression. By highlighting the importance of music, ritual, and other non-linguistic behaviors in human evolution, Mithen challenges the traditional focus on language as the defining feature of human cognition. This has important implications for fields such as education and therapy, which may benefit from incorporating more non-verbal and experiential modes of learning and healing.

Mithen’s work also has implications for our understanding of cultural diversity and universality. By identifying the common cognitive patterns that underlie human thought and behavior, he helps to explain why certain themes and motifs recur across different cultures. At the same time, by emphasizing the flexibility and adaptability of these patterns, he allows for the immense diversity of human cultural expressions. This has important implications for fields such as cross-cultural psychology and anthropology, which seek to understand the ways in which human diversity is shaped by both universal cognitive capacities and particular cultural contexts.

Finally, Mithen’s work has important implications for our understanding of ourselves as a species. By situating human cognition within the broader context of evolutionary history, he helps us to appreciate the deep roots of our mental capacities and the ways in which they have been shaped by the challenges and opportunities of our ancestral environments. At the same time, by highlighting the uniquely human capacity for cognitive fluidity and symbolic thought, he reminds us of the incredible potential of the human mind to create meaning, beauty, and knowledge.

Critiques and Controversies

Like any influential thinker, Mithen has his share of critics and detractors. Some have argued that his theories are too speculative and not sufficiently grounded in empirical evidence. Others have questioned the validity of some of his key concepts, such as cognitive fluidity and the notion of mental modules.

One common critique of Mithen’s work is that it relies too heavily on a modular view of the mind, which sees different cognitive capacities as being located in distinct neural systems or “modules.” This view has been challenged by some researchers who argue that the mind is more interconnected and holistic than the modular model suggests.

Another critique of Mithen’s work is that it downplays the importance of social and cultural factors in shaping human cognition. Some researchers have argued that Mithen’s focus on internal mental processes neglects the ways in which human thought and behavior are shaped by external social and cultural contexts.

Despite these critiques, Mithen’s work remains highly influential and widely respected within the fields of archaeology, anthropology, and cognitive science. Many researchers have built upon his ideas and used them as a starting point for their own investigations into the evolution and structure of the human mind.

Legacy

Steven Mithen’s work represents a major contribution to our understanding of human cognitive evolution and the deep roots of human culture and sociality. By integrating insights from a wide range of disciplines, from archaeology and anthropology to psychology and neuroscience, Mithen has painted a compelling picture of how the human mind emerged over the course of evolutionary history.

Central to Mithen’s approach is the concept of cognitive fluidity, which refers to the uniquely human capacity to make connections across different domains of knowledge and experience. This capacity, he argues, is what sets us apart from other species and enables us to engage in the complex symbolic and cultural practices that define human existence.

Through his investigations into the role of language, metaphor, music, and ritual in human evolution, Mithen has shed new light on the cognitive and social foundations of human culture. He has shown how these behaviors and capacities evolved as adaptations to the challenges and opportunities of our ancestral environments, and how they continue to shape our thoughts, feelings, and interactions to this day.

At the same time, Mithen’s work has important implications for our understanding of ourselves as a species. By situating human cognition within the broader context of evolutionary history, he helps us to appreciate the deep roots of our mental capacities and the ways in which they have been shaped by the demands of survival and reproduction. And by highlighting the uniquely human capacity for cognitive fluidity and symbolic thought, he reminds us of the incredible potential of the human mind to create meaning, beauty, and knowledge.

As we continue to grapple with the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century, Mithen’s insights into the evolution and structure of the human mind will undoubtedly continue to shape our understanding of ourselves and our place in the world. By building on his work and exploring new avenues for interdisciplinary research and collaboration, we can deepen our appreciation for the complex and fascinating story of human cognitive evolution.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Jungian Analysts

0 Comments