Examining the Philosophical Implications of Psychotherapy Models

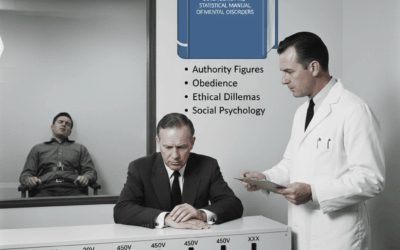

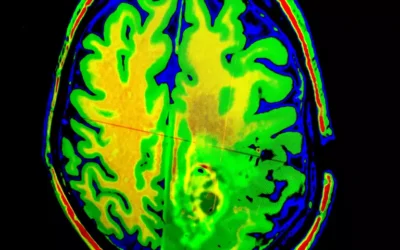

Psychotherapy, at its core, aims to alleviate mental distress, facilitate personal growth, and enhance well-being. Various therapeutic models, from psychoanalysis to cognitive-behavioral therapy, offer frameworks for understanding the human psyche and fostering positive change. However, when these models are extended beyond their clinical applications and taken to extremes, they can morph into all-encompassing metaphysical and ethical systems.

The Metaphysical Dimensions of Psychotherapy

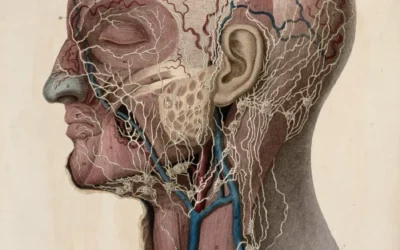

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy concerned with the fundamental nature of reality. While psychotherapy deals primarily with the inner world of the individual, many influential theorists have extrapolated their psychological insights into broader claims about the nature of the self, consciousness, and existence.

For example, Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic theory, with its emphasis on unconscious drives and the tripartite structure of the psyche (id, ego, superego), presents a particular view of human nature and motivation. When pushed to its limits, this view can be seen as a comprehensive account of the self, with the unconscious mind as the ultimate arbiter of behavior and experience.

Similarly, Carl Jung’s analytical psychology, with its concepts of archetypes, the collective unconscious, and individuation, ventures into the metaphysical realm. Jung’s theory suggests a universal substratum of shared symbols and experiences underlying individual consciousness, hinting at a transpersonal dimension to the self.

Humanistic approaches, such as those of Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow, emphasize the inherent potential for growth and self-actualization within each person. Taken to an extreme, this perspective can be seen as a metaphysical claim about the essential goodness and creativity of human nature, with self-realization as the ultimate goal of existence.

More recent models, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), are grounded in the idea that thoughts, emotions, and behaviors are interconnected and can be modified through conscious effort. When extended into a comprehensive worldview, CBT can be seen as affirming the primacy of cognition in shaping reality and the self’s capacity to reshape its own experience.

The Limits and Risks of Psychotherapy as Philosophy

While it’s an interesting thought experiment to explore the metaphysical and ethical implications of different psychotherapy models, it’s crucial to recognize the limits and potential risks of overgeneralizing these frameworks.

Psychotherapy models are designed primarily as practical tools for facilitating individual change and growth within a clinical context. They are based on empirical observations, theoretical assumptions, and the subjective experiences of practitioners and clients. While they may offer valuable insights into the human condition, they are not intended as comprehensive philosophical systems.

When therapy models are elevated to the status of all-encompassing explanations of reality or prescriptions for living, they can become dogmatic, reductionistic, and even oppressive. They may lead individuals to interpret all aspects of their experience through a narrow lens, ignoring the complexity and diversity of human existence. They can also create unrealistic expectations or a sense of failure when the ideal state portrayed by the model proves elusive.

Moreover, psychotherapy models are products of particular historical, cultural, and social contexts. They reflect the values, assumptions, and biases of their creators and the times in which they were developed. Uncritically applying these models across diverse populations and settings can lead to cultural imposition and the marginalization of alternative perspectives.

By examining the assumptions underlying different approaches, we can gain insights into the values and beliefs shaping our conceptions of mental health and well-being. We can also appreciate the diversity of perspectives and the limitations of any single framework.

Ultimately, the goal of psychotherapy is not to provide a comprehensive philosophy of life but to alleviate suffering, facilitate growth, and help individuals live more fulfilling lives. Yet in the process of exploring the depths of the psyche and the human experience, therapy can serve as a path to greater self-understanding and wisdom.

The Metaphysical Extremes of Specific Theorists

Let’s take a closer look at how some influential psychotherapists pushed their theories to metaphysical extremes:

Wilhelm Reich: Orgasms Rule the World

Wilhelm Reich, a student of Freud, took the concept of libidinal energy to a cosmic level. He proposed the existence of a universal life force called “orgone energy” that pervaded all living things. According to Reich, the free flow of orgone, particularly through sexual orgasms, was essential for physical and mental health.

Taken to its metaphysical extreme, Reich’s theory suggests that orgasms are the key to not just individual well-being but the proper functioning of the entire universe. Blocks in the flow of orgone energy, whether in individuals or societies, are seen as the root cause of all neuroses, illnesses, and even social ills. In this view, the path to a healthy, harmonious world is through the liberation of sexual energy on a grand scale.

While Reich’s ideas about orgone energy have been widely discredited, they offer a striking example of how a psychological concept can be inflated into a grandiose metaphysical system. The notion of sexual energy as a cosmic force controlling human destiny has a certain absurdist, tragicomic quality when pushed to its logical conclusion.

Carl Jung: Archetypes All the Way Down

Carl Jung’s theory of archetypes and the collective unconscious already verges on the metaphysical, positing universal, inherited patterns that structure human experience. However, some Jungian thinkers have taken these ideas even further.

In the more esoteric strands of Jungian thought, archetypes are not just psychological patterns but fundamental building blocks of reality itself. Everything from atoms to galaxies is seen as manifesting archetypal principles. The collective unconscious becomes a kind of cosmic mind, with individual psyches as its localized expressions.

Pushed to its metaphysical limit, this view suggests that understanding archetypes is the key to unlocking the secrets of the universe. The path to enlightenment lies in integrating all the archetypal aspects of the self and aligning with the grand archetypal patterns that shape existence.

While Jung himself was more measured in his claims, some of his followers have transformed his psychological insights into a sweeping metaphysical vision. The result is a kind of archetypal mysticism that sees symbols and myths as the deepest truths of reality.

Abraham Maslow: Self-Actualization as the Meaning of Life

Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs culminates in the concept of self-actualization—the realization of one’s full potential and the pinnacle of psychological development. For Maslow, self-actualization represents the highest human aspiration and the key to a fulfilling life.

When taken to a metaphysical extreme, self-actualization becomes the ultimate purpose not just of individuals but of human existence as a whole. The universe is seen as a vast arena for the unfolding of human potential, with the self-actualized person as the apex of cosmic evolution.

In this view, all of life’s challenges and obstacles are merely opportunities for growth and self-realization. Suffering and setbacks are recast as necessary steps on the path to personal transcendence. The measure of a life’s worth becomes the degree to which one has achieved self-actualization.

While Maslow’s ideas have been influential in humanistic psychology, elevating self-actualization to a metaphysical imperative can create a pressure-filled, perfectionist ethos. It can also devalue the experiences of those who may not fit the mold of the self-actualized ideal.

Alfred Adler: The Creative Self and the Striving for Superiority

Alfred Adler’s Individual Psychology emphasized the “creative self” as the agent of personal growth and the “striving for superiority” as a universal human drive. Adler saw this striving not as a quest for dominance but as a desire for mastery, completion, and contribution to society.

Taken to its metaphysical limit, Adler’s theory suggests that the universe itself is a manifestation of the creative self, constantly evolving and actualizing its potential. The striving for superiority becomes the fundamental impulse of all existence, with each entity seeking its own form of excellence and wholeness.

In this view, the purpose of human life is to align oneself with this cosmic striving, to embrace one’s creative power and make a unique contribution to the greater whole. Neurosis and dysfunction arise when this natural striving is suppressed or misdirected, leading to feelings of inferiority and a lack of social interest.

While Adler’s ideas offer an empowering vision of human potential, pushing them to a metaphysical extreme may neglect the importance of acceptance, cooperation, and the value of ordinariness. Not everyone needs to be a cosmic creator to live a meaningful life.

Viktor Frankl: The Search for Meaning as a Cosmic Quest

Viktor Frankl, the founder of logotherapy, saw the search for meaning as the primary human motivation. Drawing on his experiences in Nazi concentration camps, Frankl argued that even in the most extreme circumstances, individuals can find meaning by choosing their attitude and actions.

When extended to a metaphysical level, Frankl’s ideas suggest that the universe itself is imbued with meaning, and that the human search for significance is a reflection of a cosmic quest. Each individual’s life becomes a microcosm of the greater struggle to find purpose and value in existence.

In this view, suffering and adversity are not mere obstacles but opportunities for growth and the discovery of deeper meaning. The ultimate goal of human life is not happiness but the actualization of values and the fulfillment of one’s unique purpose in the grand scheme of things.

While Frankl’s emphasis on meaning and responsibility is inspiring, elevating the search for meaning to a cosmic level may create unrealistic expectations and a sense of grandiosity. It may also minimize the role of circumstance and privilege in shaping individuals’ capacities to find and create meaning.

Abraham Maslow: Self-Transcendence as the Pinnacle of Development

Abraham Maslow, a pioneer of humanistic psychology, is best known for his hierarchy of needs, which culminates in the drive for self-actualization. However, in his later work, Maslow posited an even higher level of development: self-transcendence.

For Maslow, self-transcendence represents the pinnacle of human growth, a state in which individuals move beyond self-actualization to identify with something greater than themselves. This might involve peak experiences, mystical unity, or the pursuit of universal values and goals.

When pushed to its metaphysical extreme, Maslow’s theory suggests that self-transcendence is not just a human potential but the ultimate direction of the universe itself. Each entity, from atoms to galaxies, is seen as striving toward ever-higher forms of complexity, consciousness, and integration.

In this view, the purpose of human life is to participate in this cosmic evolution, to transcend the limits of the individual self and merge with the greater whole. Personal growth and well-being become byproducts of aligning oneself with this universal drive toward transcendence.

While Maslow’s vision is lofty and inspiring, it can also be seen as a form of spiritual bypassing, minimizing the importance of embodiment, relationship, and the practical challenges of daily life. It may foster a sense of elitism or disconnection from the mundane realities of human existence.

Roberto Assagioli: The Higher Self as the Key to Cosmic Evolution

Roberto Assagioli, the founder of psychosynthesis, proposed the concept of the “higher self” as a transpersonal essence within each individual. For Assagioli, the higher self represents the source of wisdom, creativity, and the drive for growth and integration.

Taken to its metaphysical extreme, Assagioli’s theory suggests that the higher self is not just a psychological construct but a cosmic principle. Each individual’s higher self is seen as a localized expression of a universal intelligence or consciousness guiding the evolution of all existence.

In this view, the purpose of human life is to actualize the potential of the higher self, to align the personality with its transpersonal essence and participate in the greater work of cosmic evolution. Psychosynthesis becomes not just a therapeutic approach but a spiritual path, a means of consciously cooperating with the higher self’s agenda.

While Assagioli’s ideas offer a hopeful and expansive vision of human potential, they can also be seen as a form of metaphysical speculation, blurring the lines between psychology and spirituality. Elevating the higher self to a cosmic principle may foster a sense of grandiosity or disconnection from the challenges and limitations of embodied existence.

Ken Wilber: Integral Theory as a Grand Metaphysical Synthesis

Ken Wilber, while not a psychotherapist in the strict sense, has had a significant impact on the field through his integral theory. Wilber’s aim is to create a comprehensive framework that integrates various psychological, philosophical, and spiritual traditions into a coherent whole.

At the heart of Wilber’s theory is the concept of holons—entities that are simultaneously wholes in themselves and parts of larger wholes. Wilber sees the universe as a vast hierarchy of holons, evolving toward ever-greater complexity, consciousness, and integration.

In Wilber’s metaphysical vision, human development recapitulates the evolution of the cosmos, with each individual’s growth reflecting the unfolding of universal patterns. The goal of human life is to ascend through the various stages and levels of consciousness, ultimately reaching a state of nondual awareness and cosmic unity.

While Wilber’s integral theory offers a grand and inclusive vision, it can also be seen as a form of metaphysical overreach, attempting to subsume all of reality into a single, totalizing framework. It may neglect the irreducible diversity and mystery of existence in favor of a neat, hierarchical model.

The Value and Limits of Metaphysical Speculation

Examining the metaphysical implications of psychotherapy models can be a fascinating and illuminating exercise. It reveals the hidden assumptions and ultimate conclusions of these frameworks when extended beyond their clinical applications.

However, it’s crucial to approach such speculations with a critical eye and a sense of perspective. While the metaphysical visions of thinkers like Reich, Jung, and Maslow can be imaginative and thought-provoking, they are not scientific truths or prescriptions for living. When taken too literally or applied too rigidly, they can become dogmatic, limiting, or even harmful.

At the same time, engaging with the metaphysical dimensions of psychotherapy can enrich our understanding of the human condition and the quest for meaning and growth. It can inspire us to think more deeply about the nature of the self, the psyche, and reality as a whole.

The key is to hold these metaphysical speculations lightly, as provocative possibilities rather than fixed certainties. By maintaining a sense of humor, humility, and openness, we can explore the philosophical implications of psychotherapy without being constrained by them. In the end, the value of these ideas lies not in their literal truth but in their ability to stimulate insight, awaken wonder, and expand our horizons of understanding.

0 Comments