How do Jungians and Freudians Conceptualize Trauama Differently?

The understanding of trauma and its impact on the human psyche has been a central concern for depth psychology since its inception. However, the two pioneering schools of thought in this field, Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis and Carl Jung’s analytical psychology, developed divergent frameworks for conceptualizing the nature and impact of traumatic experiences.

Freud’s model of the psyche emphasized the central role of instinctual drives, particularly sexual and aggressive impulses, in shaping psychological development. He saw trauma primarily as an overwhelming excitation of these drives that breached the ego’s protective barriers, leading to a profound disruption of psychic equilibrium. Traumatic experiences were seen as fundamentally dysregulating events that flooded the psyche with unbound energy, triggering primitive defense mechanisms like repression and dissociation.

In Freud’s view, the key to understanding trauma lay in uncovering the repressed memories and fantasies associated with the traumatic event, particularly those tinged with forbidden sexual or aggressive wishes. The goal of therapy was to bring these unconscious contents into conscious awareness, thereby allowing the ego to integrate them and restore psychic balance.

Jung, by contrast, saw the psyche as inherently relational and oriented towards growth and meaning. For Jung, the key drivers of development were not instinctual drives but archetypal patterns and potentialities that sought expression through the individual’s life experiences. Trauma, in this view, was not just a dysregulating event but a profound disruption of the psyche’s natural drive towards wholeness and individuation.

Jung understood trauma as an overwhelming experience that fragmented the psyche, splitting off unbearable affect and memory into dissociated complexes. These trauma complexes, organized around archetypal cores, operated autonomously from the ego, warping perception, emotion, and behavior in an effort to protect the self from further harm. The goal of therapy, for Jung, was not just symptom relief but a profound transformation of the personality through the integration of these split-off parts.

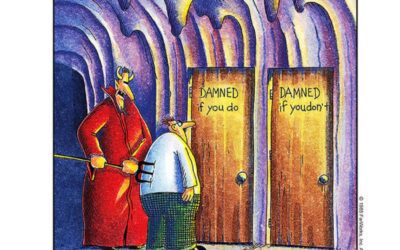

Importantly, Jung saw trauma not just as a pathological event but potentially as a catalyst for growth. If the traumatic material could be consciously engaged and integrated, it could lead to a greater wholeness and vitality of the personality. The role of the therapist, then, was not just to uncover repressed content but to facilitate a symbolic process of healing and transformation.

These different emphases – on instinctual drives versus archetypal patterns, on uncovering the repressed versus integrating the dissociated, on restoring equilibrium versus fostering individuation – set Freudian and Jungian theories on divergent paths in their understanding of trauma.

Freudian theory evolved towards a greater focus on the role of early relationships in shaping the psyche, seeing trauma through the lens of ruptured attachments and disturbed object relations. This reached its height with the work of Melanie Klein and the British Object Relations school, which saw the internalization of early experiences, particularly those of deprivation and anxiety, as the bedrock of personality development and psychopathology.

Jungian theory, while slower to integrate developmental perspectives, came to understand trauma through the lens of archetypal defenses and the complex interplay of ego and Self. Jungian analysts like Michael Fordham and Donald Kalsched explored how early relational trauma catalyzed a self-protective dissociation of the psyche, with the traumatized “child” part split off and enveloped by powerful archetypal defenses.

Despite these differences in emphasis, in the practice of depth work, Freudian and Jungian approaches have found significant areas of convergence. Both recognize the central role of unconscious processes in shaping experience, the enduring impact of early relational patterns on later functioning, and the transformative potential of the therapeutic relationship as a vehicle for reworking traumatic experiences.

Contemporary Jungian analysts like Donald Kalsched have integrated object relations concepts and attachment research into their understanding of trauma, enriching the archetypal perspective with a greater appreciation for developmental forces. At the same time, many contemporary Freudian thinkers have incorporated Jungian concepts like the collective unconscious and the Self into their models of the psyche.

In the following sections, we will explore some key post-Freudian contributions to trauma theory, and then delve into Donald Kalsched’s integrative model of the psyche’s response to overwhelming trauma. Kalsched’s work, which weaves together Jungian, object relations, and contemporary trauma theories, offers a profound and nuanced understanding of how the psyche both fragments and seeks wholeness in the face of devastating experiences.

His concept of the archetypal self-care system, a complex dyad of traumatized and protective parts, sheds light on the deep structure of traumatic experience and the powerful forces that shape the psyche’s response to overwhelming events. By following the thread of his work, we can come to a richer appreciation of both the psyche’s vulnerability to trauma and its profound capacity for resilience and transformation.

Post-Freudian Perspectives

Karen Horney’s Three Neurotic Types

Karen Horney was a prominent neo-Freudian psychoanalyst who developed a theory of neurosis based on disturbed human relationships. She proposed three neurotic types that represent distinct ways of coping with anxiety stemming from early relational conflicts:

- The compliant type: Moves towards others, seeking affection and approval to allay anxiety. Fears abandonment and being unlovable.

- The aggressive type: Moves against others, seeking power and control to master anxiety. Fears vulnerability and being victimized.

- The detached type: Moves away from others, seeking self-sufficiency to avoid anxiety. Fears engagement and being influenced.

For Horney, neurosis arises as a rigid, anxiety-driven orientation that inhibits flexibility and wholeness. Healthy development, by contrast, allows for a dynamic balance between these tendencies. Her theory, rooted more in interpersonal than instinctual dynamics, foreshadows later relational approaches to trauma.

Melanie Klein’s Object Relations

Melanie Klein, a key figure in the British Object Relations school, further shifted psychoanalytic thinking towards the inner world of internalized relationships. For Klein, the infant’s primary concern is establishing a good relationship with the mother (as a composite of nurturing “good” and frustrating “bad” parts), managed through cycles of projection and introjection.

In Klein’s view, unintegrated aggressive and libidinal impulses are projected outward onto the “bad” object (mother), while idealizing libidinal feelings are introjected to form the core of the developing ego. If the infant is met with a “good enough” maternal environment, these projections can be contained and re-introjected in a modified form, building increasing tolerance for ambivalence. However, in the face of severe frustrations or a non-containing environment, aggression may be turned back upon the self, shattering the integrity of the ego and internal objects.

Klein saw this dynamic repeating throughout life, with later traumas reactivating and reinforcing unintegrated self-other states. Her theories laid the groundwork for later models of fragmentation, dissociation, and the role of containment in healing traumatized internal object relations.

D.W. Winnicott and the Impact of Early Environment

Donald Winnicott further elaborated the impact of the early holding environment in shaping the developing psyche. For Winnicott, the “good enough mother” allows the child to grow out of absolute dependence, through a phase of relative dependence, and towards increasing autonomy. Along the way, the caregiver contains and soothes unbearable affects, allowing them to be integrated as tolerable experience.

Where the environment fails to protect the infant from impingement or falls short in containment, development is distorted through “primitive agonies” – raw unbearable feeling states that threaten psychic annihilation. To cope, the child develops a protective “false self” while walling off the wounded “true self” behind powerful defenses.

Winnicott saw the therapeutic relationship as a “transitional space” that could hold the patient’s projections and regressions. By surviving the patient’s aggression and hate over the inevitable failures of the therapist, a more integrated self capable of ambivalence and concern could gradually emerge. His theories greatly influenced how later analysts conceptualized the dissociative defenses around early trauma and the conditions needed to heal.

The Jungian Perspective: Donald Kalsched’s Work on Trauma

Overview of Kalsched’s Model

Jungian analyst Donald Kalsched has developed a comprehensive model of the psyche’s response to overwhelming trauma that integrates contemporary trauma theory, object relations concepts, and archetypal psychology. At the heart of his model is the concept of the archetypal self-care system.

For Kalsched, trauma that occurs in early life and exceeds the child’s capacity to integrate leads to a splitting of the psyche. The vulnerable, traumatized child part is split off and encapsulated, while a powerful archetypal defense – the self-care system – is constellated to protect this fragile part. This system has both persecutory and protective aspects, attacking the child’s vulnerability as a liability while fiercely guarding against re-traumatization.

The self-care system, made up of dissociated self-other imagos and affect states, generates an inner “daemonic” world shaped by the traumatic experience. In this world, the trauma is endlessly reenacted, with the self oscillating between victim and perpetrator, in an effort to manage the overwhelming affects associated with the original wound.

This system, while initially protective, becomes increasingly rigid and autonomous, hijacking later relationships through traumatic reenactment. The child part longs for a salvational object to heal the wounds of the past, but actual relationships inevitably disappoint this fantasy and activate the defensive system. A traumatic “archetypal dehiscence” occurs, disrupting the continuity of self and other.

For Kalsched, healing involves a gradual process of containment, disillusionment, and integration within the therapeutic relationship. As the therapist holds and bears witness to the dissociated trauma without retaliation, the defensive system is gradually softened. This allows for a progressive experiencing of the traumatic affects and unmet needs within a context of safety, fostering the growth of the stunted child part.

Mourning the original trauma and the shattered fantasy of an ideal childhood enables the emergence of a more integrated and fluid sense of self. The inner caregiver system is humanized, able to provide both protection and nurturance to the child part. Ultimately, this enables a fuller engagement with self and others in the present.

Trauma and the Soul

In his book “Trauma and the Soul,” Kalsched further explores the spiritual dimensions of trauma and recovery. He posits that the dissociative defenses around early trauma not only protect the personal self but also a vital transpersonal essence – what Jung called the Self. This spiritual core, which holds the potential for growth and individuation, must be shielded from annihilation.

However, in the process of protection, the soul is also imprisoned, cut off from life-giving connections to self, other, and the numinous. The journey of recovery, then, involves not only a psychological healing but a re-ensoulment – a restoration of the vital links between the ego and the deep self.

Kalsched sees this process through an alchemical lens, drawing on Jung’s concept of the mysterium coniunctionis – the mystery of the conjunction of opposites. In the therapeutic crucible, the dissociated fragments of self and the archetypal energies that both wound and heal are brought together and transformed. The base material of trauma is transmuted into the gold of the individuated self.

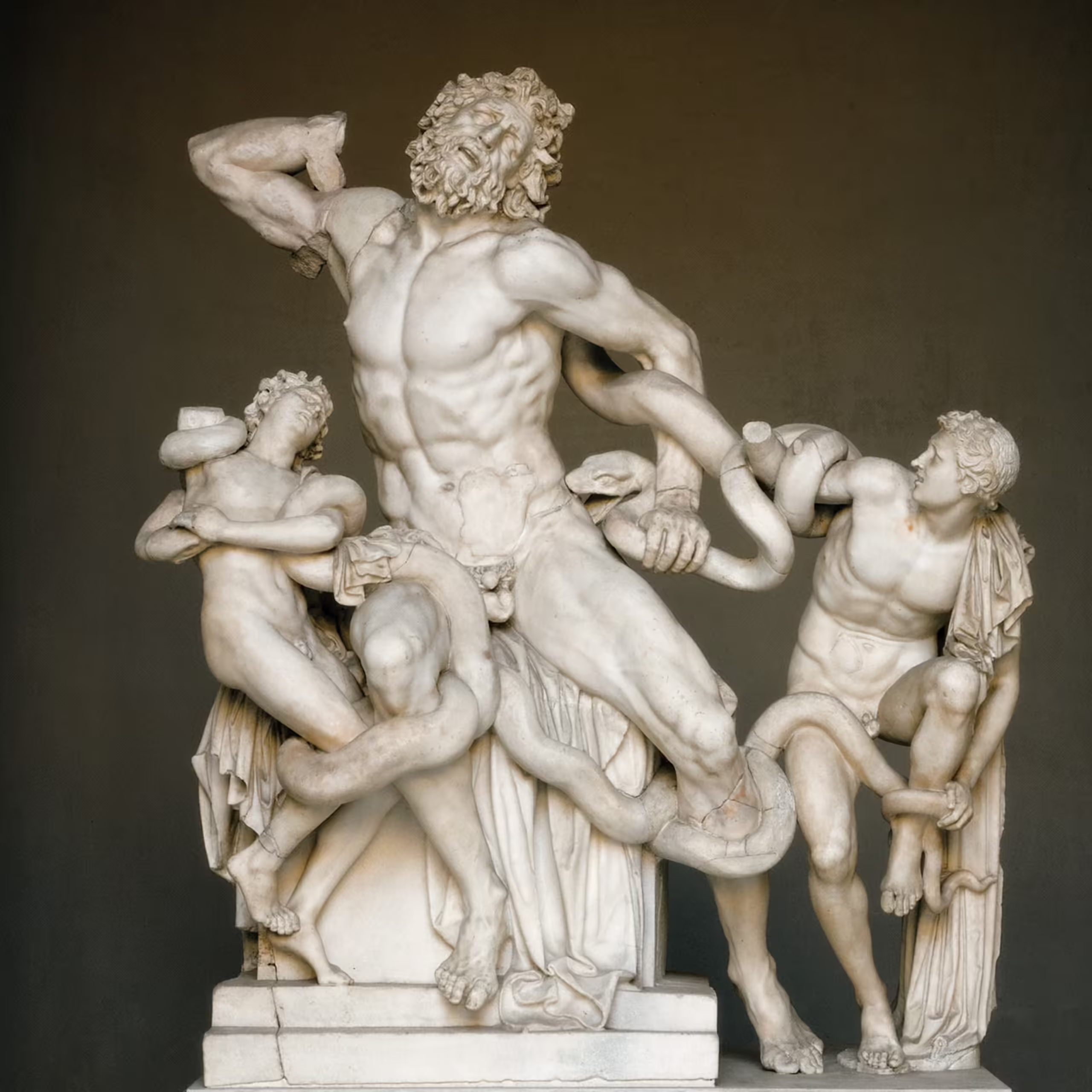

This process involves a descent into the inner underworld of the trauma complex, facing the daimonic powers that reside there. The therapist serves as a guide and container, enabling the patient to confront the archetypal forces without being overwhelmed. Gradually, as the split-off parts are reintegrated, the ego is reconnected to the resources of the deep self, enabling a more authentic and embodied way of being.

The Inner World of Trauma

In “The Inner World of Trauma,” Kalsched offers a detailed exploration of the archetypal self-care system and its manifestations in clinical work. He presents in-depth case studies illustrating how the dissociative defenses structure the patient’s inner experience and relational patterns.

Kalsched illuminates how the self-care system generates an elaborate inner fantasy world, peopled by tyrannical inner objects that keep the child part imprisoned. This world is marked by a collapse of psychological space, where inner and outer are confused and time is frozen around the traumatic experience. Dreams and fantasies are repetitive and circular, reflecting the static nature of the trauma complex.

Paradoxically, the self-care system also includes angelic or idealized figures that offer hope of rescue. These imagos, often drawn from childhood stories or myths, represent the yearning for a salvational object to undo the trauma. However, they ultimately collude with the persecutory objects to maintain the dissociative defenses.

Kalsched maps how these inner dynamics are transferred onto the therapeutic relationship, with the therapist alternately idealized as savior and demonized as perpetrator. He emphasizes the importance of the therapist’s capacity to withstand these projections without retaliation or collapse, providing a new relational experience that challenges the dominance of the trauma complex.

As the therapist holds the “unthought knowns” of the patient’s trauma, the dissociated affects and self-states can begin to be verbalized and integrated. The patient incrementally risks experiencing the vulnerability and dependency that have been unbearable, developing a more coherent narrative of the self.

Kalsched also explores how the self-care system manifests in specific clinical presentations, such as borderline and narcissistic conditions. He sees these as different enactments of the dissociative defenses, requiring tailored approaches to gradually soften the traumatic organization of the psyche.

Throughout, Kalsched emphasizes the delicate balance between maintaining the needed protective function of the self-care system and gently challenging its hegemony. The goal is not to eliminate the archetypal defenses but to foster a more flexible and integrated ego that can navigate both inner and outer worlds more fluidly.

Further Post-Jungian Elaborations

In recent decades, a number of post-Jungian thinkers have made significant contributions to the understanding of trauma and its treatment, integrating Jungian concepts with contemporary developments in attachment theory, neuroscience, relational psychoanalysis, and beyond. This section will explore some of these key elaborations, highlighting the ways in which they have enriched and expanded the Jungian approach to trauma.

One seminal figure in this regard is Michael Fordham, a British Jungian analyst who pioneered the application of developmental perspectives to Jungian theory. Fordham’s model of the “primary self” emphasized the infant’s innate drive towards integration and wholeness, a drive that was either supported or hindered by the quality of early caregiving relationships.

For Fordham, trauma represented a profound disruption of the self’s natural deintegrative and reintegrative processes. When the early environment failed to provide sufficient containment and attunement, the infant’s developing self would fragment into dissociated self-states, each holding a split-off aspect of the personality. Healing, in this perspective, involved a gradual re-integration of these dissociated states within the context of a holding therapeutic relationship.

Fordham’s emphasis on the self’s inherent integrative capacities and its vulnerability to early relational trauma laid the groundwork for subsequent post-Jungian explorations of the developmental dimensions of trauma. His work underscored the importance of considering not just the symbolic and archetypal aspects of traumatic experience, but also its roots in the earliest stages of self-formation.

Building on Fordham’s contributions, Jean Knox has sought to bridge Jungian theory with contemporary findings in cognitive science and attachment research. Knox’s model of the “archetypally-structured emergent mind” proposes that archetypes are not just innate psychic structures, but also reflect the self-organizing properties of the developing brain.

According to Knox, early relational experiences shape the developing neural circuitry of the brain, creating patterns of emotional reactivity and behavioral response that mirror the quality of attachment. Secure attachment facilitates the development of a coherent and flexible sense of self, while insecure or disorganized attachment can lead to rigidity, dissociation, and a vulnerability to later trauma.

Knox’s work offers a neurobiological underpinning for the Jungian understanding of trauma, suggesting that the dissociative defenses and archetypal activation seen in traumatic states have their roots in the basic survival circuitry of the brain, circuitry that is fundamentally shaped by early relational experiences.

The role of early relational patterns in shaping vulnerability to trauma is further elaborated in the work of Marcus West. West’s model emphasizes the centrality of implicit relational knowing – the unconscious patterns of relating that are encoded in the earliest stages of development – in forming the individual’s sense of self and other.

For West, traumatic experiences disrupt these implicit relational patterns, leading to a profound sense of disconnection and disorientation. Healing involves a gradual re-working of these patterns within the therapeutic relationship, as the patient internalizes a new experience of being seen, understood, and held in the mind of the therapist.

West’s contributions highlight the profoundly relational nature of trauma and its healing, suggesting that what is ultimately being transformed in the therapeutic process is not just the patient’s intrapsychic world, but their deeply-rooted ways of being with others.

More recently, post-Jungian thinkers have begun to explore the complex interplay of personal and collective trauma, particularly in the context of social and historical oppression. Analysts like Fanny Brewster and Konoyu Nakamura have examined how racial trauma and cultural dislocation can lead to a profound fragmentation of the self, a fragmentation that is perpetuated by ongoing dynamics of oppression and marginalization.

This work expands the Jungian understanding of trauma to encompass not just personal experiences of overwhelming affect, but also the collective traumas of history and culture. It suggests that healing, in this context, involves not just a personal integration, but also a reclaiming of cultural identity and a re-connection with the sustaining resources of community.

Finally, some contemporary post-Jungian thinkers have returned to the spiritual and existential dimensions of trauma that were central to Jung’s own understanding of the psyche. Analysts like Lionel Corbett and Donald Sandner have explored how traumatic experience can precipitate a profound crisis of meaning, shattering the individual’s fundamental trust in the coherence and benevolence of the world.

Healing, in this view, necessitates not just a psychological integration, but a spiritual transformation – a re-connection with the numinous dimensions of existence that trauma so often obscures. This perspective locates the ultimate challenge of trauma not just in the restoration of intrapsychic or interpersonal coherence, but in the reclaiming of a sense of existential grounding and purpose.

Taken together, these post-Jungian elaborations reveal the depth and diversity of contemporary Jungian engagement with trauma. They expand the Jungian frame to encompass developmental, neurobiological, relational, cultural, and spiritual perspectives, while remaining rooted in the core Jungian understanding of the psyche’s drive towards wholeness and meaning.

Lessons for the Future

The synthesis of post-Freudian object relations theory and Jungian archetypal psychology offers a powerful lens for understanding the impact of trauma on the psyche and the path to healing. Donald Kalsched’s work, in particular, provides a nuanced and comprehensive model of how early relational trauma catalyzes a dissociative self-care system that preserves life but at the cost of vitality and relatedness.

Kalsched’s integration of developmental and archetypal perspectives illuminates the universal themes that underlie the experience of trauma and recovery. His concept of the archetypal self-care system, with its daimonic and angelic aspects, captures the paradoxical nature of the psyche’s defenses – simultaneously protective and imprisoning.

His clinical approach, grounded in a deep respect for the survival value of the dissociative defenses, emphasizes the transformative power of the therapeutic relationship. By providing a containing and witnessing presence, the therapist enables a gradual softening of the traumatic organization and a restoration of the vital links between ego and self.

Ultimately, Kalsched’s work points towards the profound potential for growth and healing that resides within even the most traumatized psyche. By descending into the inner world of trauma and facing the daimonic with compassion and courage, the lost child of the self can be reclaimed and the soul’s journey towards wholeness renewed.

This synthesis of post-Freudian and post-Jungian perspectives offers a rich and hopeful vision of the human psyche’s resilience in the face of trauma. It challenges us to approach the complex manifestations of dissociation with patience, humility, and a deep faith in the psyche’s inherent drive towards healing and wholeness.

Bibliography

Bromberg, P. M. (2011). The Shadow of the Tsunami: and the Growth of the Relational Mind. Routledge.

Davies, J. M., & Frawley, M. G. (1994). Treating the Adult Survivor of Childhood Sexual Abuse: A Psychoanalytic Perspective. Basic Books.

Fairbairn, W. R. D. (1954). An Object-Relations Theory of the Personality. Basic Books.

Fordham, M. (1985). Explorations into the Self. Academic Press.

Freud, S. (1920). Beyond the Pleasure Principle. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XVIII (1920-1922): Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Group Psychology and Other Works, 1-64.

Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence – From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror. Basic Books.

Jacoby, M. (1999). Jungian Psychotherapy and Contemporary Infant Research: Basic Patterns of Emotional Exchange. Routledge.

Jung, C. G. (1934). Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious. The Collected Works of C. G. Jung, Vol. 9, Pt. 1.

Kalsched, D. (1996). The Inner World of Trauma: Archetypal Defenses of the Personal Spirit. Routledge.

Kalsched, D. (2013). Trauma and the Soul: A Psycho-Spiritual Approach to Human Development and its Interruption. Routledge.

Kalsched, D. (2017). The Jung-Kirsch Letters: The Correspondence of C.G. Jung and James Kirsch. Routledge.

Kalsched, D. (2021). Trauma and the Soul: Psychoanalytic Approaches to the Inner World of Traumatized People. Routledge.

Klein, M. (1946). Notes on Some Schizoid Mechanisms. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 27, 99-110.

Ogden, T. H. (1989). The Primitive Edge of Experience. Jason Aronson.

Schore, A. N. (2012). The Science of the Art of Psychotherapy (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). W. W. Norton & Company.

Segal, H. (1964). Introduction to the Work of Melanie Klein. Basic Books.

Stein, M. (2006). The Principle of Individuation: Toward the Development of Human Consciousness. Chiron Publications.

Van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Viking.

Winnicott, D. W. (1960). The Theory of the Parent-Infant Relationship. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 41, 585-595.

Winnicott, D. W. (1971). Playing and Reality. Tavistock.

Further Reading

Abram, J. (1996). The Language of Winnicott: A Dictionary of Winnicott’s Use of Words. Karnac Books.

Arendt, H. (1976). The Origins of Totalitarianism. Harcourt Brace & Company.

Bollas, C. (1987). The Shadow of the Object: Psychoanalysis of the Unthought Known. Columbia University Press.

Casement, A. (2006). Who Owns Jung? Routledge.

Edinger, E. F. (1972). Ego and Archetype: Individuation and the Religious Function of the Psyche. Putnam.

Ellenberger, H. F. (1970). The Discovery of the Unconscious: The History and Evolution of Dynamic Psychiatry. Basic Books.

Fairbairn, W. R. D. (1952). Psychoanalytic Studies of the Personality. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Fonagy, P., Gergely, G., Jurist, E. L., & Target, M. (2002). Affect Regulation, Mentalization, and the Development of the Self. Other Press.

Greenberg, J. R., & Mitchell, S. A. (1983). Object Relations in Psychoanalytic Theory. Harvard University Press.

Guntrip, H. (1971). Psychoanalytic Theory, Therapy, and the Self. Basic Books.

Hillman, J. (1979). The Dream and the Underworld. Harper & Row.

Homans, P. (1979). Jung in Context: Modernity and the Making of a Psychology. University of Chicago Press.

Hubback, J. (1998). From Dawn to Dusk: An Autobiography. Chiron Publications.

Jacobi, J. (1959). Complex/Archetype/Symbol in the Psychology of C. G. Jung. Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1953). Two Essays on Analytical Psychology. The Collected Works of C. G. Jung, Vol. 7.

Jung, C. G. (1964). Man and His Symbols. Doubleday.

Knox, J. (2003). Archetype, Attachment, Analysis: Jungian Psychology and the Emergent Mind. Brunner-Routledge.

Levine, P. A. (1997). Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma: The Innate Capacity to Transform Overwhelming Experiences. North Atlantic Books.

Meckel, D. J., & Moore, R. L. (1992). Self and Liberation: The Jung/Buddhism Dialogue. Paulist Press.

Merchant, J. (2016). Shamans and Analysts: New Insights on the Wounded Healer. Routledge.

Miller, A. (1981). The Drama of the Gifted Child: The Search for the True Self. Basic Books.

Moore, R., & Gillette, D. (1991). King, Warrior, Magician, Lover: Rediscovering the Archetypes of the Mature Masculine. HarperSanFrancisco.

Neumann, E. (1954). The Origins and History of Consciousness. Princeton University Press.

Perera, S. B. (1981). Descent to the Goddess: A Way of Initiation for Women. Inner City Books.

Samuels, A. (1985). Jung and the Post-Jungians. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Samuels, A., Shorter, B., & Plaut, F. (1986). A Critical Dictionary of Jungian Analysis. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Sandner, D. F., & Beebe, J. (1995). Psychopathology and Analysis. In M. Stein (Ed.), Jungian Analysis (2nd ed.) (pp. 322-330). Open Court.

Schwartz-Salant, N. (1989). The Borderline Personality: Vision and Healing. Chiron Publications.

Siegel, D. J. (1999). The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape who We are. Guilford Press.

Stein, M. (1998). Jung’s Map of the Soul: An Introduction. Open Court.

Stern, D. N. (1985). The Interpersonal World of the Infant: A View from Psychoanalysis and Developmental Psychology. Basic Books.

Stevens, A. (1982). Archetype: A Natural History of the Self. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Ulanov, A. B. (1971). The Feminine in Jungian Psychology and in Christian Theology. Northwestern University Press.

Winnicott, D. W. (1958). Collected Papers: Through Paediatrics to Psycho-Analysis. Tavistock.

Woodman, M. (1982). Addiction to Perfection: The Still Unravished Bride: A Psychological Study. Inner City Books.

Young-Eisendrath, P., & Dawson, T. (Eds.). (1997). The Cambridge Companion to Jung. Cambridge University Press.

Zabriskie, B. (2000). Orphans of the Heart: The Developmental Impact of Trauma and Dissociation. In A. Casement (Ed.), Post-Jungians Today: Key Papers in Contemporary Analytical Psychology (pp. 123-138). Routledge.

0 Comments