Why do we believe in Vampires?

Vampires have long captured the human imagination, appearing in the folklore, literature, and popular culture of societies across the globe. These enigmatic figures, often depicted as undead beings who sustain themselves by feeding on the life essence of the living, have roots that run deep in human history and mythology (Beresford, 2008). The persistent fascination with vampires can be attributed to their ability to embody and reflect the fears, desires, and cultural anxieties of the societies that give rise to them (Barber, 1988).

From an anthropological perspective, the vampire serves as a potent symbol through which cultures grapple with fundamental aspects of the human experience, such as death, sexuality, power, and the relationship between the individual and society (Rickels, 1999). By tracing the evolution of the vampire myth through history and across cultures, we can gain valuable insights into how different societies have understood and negotiated these fundamental issues (Melton, 2011).

Mythological and Folkloric Origins

The concept of the vampire can be traced back to ancient myths and legends from around the world, many of which feature creatures that bear striking resemblances to the modern vampire. In Mesopotamian mythology, the demon Lilith was said to seduce and kill men, drinking their blood and eating their flesh (Patai, 1990). The ancient Greeks told tales of Lamia, a child-devouring monster, and the striges, nocturnal bird-like creatures that fed on human flesh and blood (West, 1995).

Vampire-like beings also appear in the folklore of cultures across Asia, Africa, and the Americas. The jiangshi of Chinese mythology are reanimated corpses that hop around at night, attacking the living and draining their qi, or life force (Chiang & Chiang, 2007). In parts of Africa, the Ewe people tell of the adze, a vampiric entity that possesses humans and compels them to drink the blood of their kin (Meyer, 1995). And among the Maya of Central America, the bat god Camazotz was associated with night, death, and blood sacrifice (Miller & Taube, 1993).

These diverse mythological and folkloric traditions suggest that the vampire archetype taps into deep-seated human fears and fascinations that transcend cultural boundaries. The recurring themes of blood, death, and predation hint at the vampire’s enduring symbolic power as a manifestation of the dark side of human nature and the taboo desires that lurk beneath the surface of civilized society (Frayling, 1991).

The Medieval European Vampire

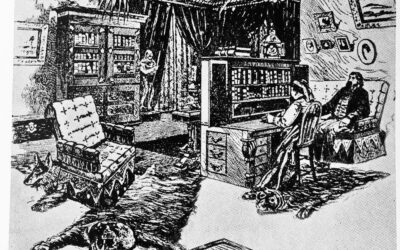

The vampire myth as we know it today began to take shape in medieval Europe, particularly in the Balkans and Eastern Europe. During this period, the Christian Church’s attempts to suppress pagan beliefs and practices led to the demonization of many ancient folk traditions (McClelland, 2006). In this context, the vampire came to be seen as a malevolent, soul-stealing entity that represented a threat to the spiritual and social order (Perkowski, 1989).

Belief in vampires was fueled by a combination of religious superstition, fear of disease and death, and the limitations of contemporary medical knowledge. In an era when the causes of illness and death were poorly understood, vampires provided a convenient explanation for mysterious afflictions and sudden fatalities (Barber, 1988). The idea that the dead could rise from their graves to prey upon the living also served as a powerful deterrent against sin and social transgression, reinforcing the authority of the Church and the feudal social hierarchy (Murgoci, 1926).

The Rise of the Literary Vampire

The vampire entered Western literature in the early 19th century, with the publication of works like John Polidori’s “The Vampyre” (1819) and Sheridan Le Fanu’s “Carmilla” (1872). These stories introduced many of the tropes and conventions that would come to define the literary vampire, such as the seductive aristocratic bloodsucker and the lesbian vampire (Auerbach, 1995).

But it was Bram Stoker’s “Dracula” (1897) that truly solidified the vampire’s place in the Western cultural imagination. Stoker’s novel synthesized elements from various folkloric traditions and earlier literary works to create an iconic vampire figure that embodied Victorian anxieties about sexuality, foreignness, and the erosion of traditional social boundaries (Senf, 1998). Count Dracula, with his old-world aristocratic lineage and his predatory sexuality, represented a threat to the moral and social order of Victorian England, while also exerting a seductive fascination over the novel’s characters and readers alike (Craft, 1984).

The success of “Dracula” spawned a host of imitators and adaptations, firmly establishing the vampire as a staple of horror and gothic fiction. Over the course of the 20th century, the vampire would continue to evolve in literature and popular culture, reflecting changing social mores and cultural preoccupations (Gelder, 1994).

The Modern Vampire: Subversion and Romance

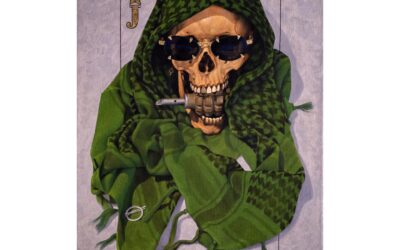

In the latter half of the 20th century, the vampire underwent a significant transformation in literature and film, as authors and filmmakers began to subvert traditional vampire tropes and explore new dimensions of the vampire mythos. Anne Rice’s “Interview with the Vampire” (1976) and its sequels presented a sympathetic, introspective vampire protagonist who grappled with existential angst and the burden of immortality (Hoppenstand & Browne, 1996). This more humanized portrayal of the vampire paved the way for the emergence of the “sympathetic vampire” as a recurring figure in modern vampire fiction (Overstreet, 2006).

The 1990s and 2000s saw the rise of the paranormal romance genre, which recast the vampire as a romantic hero and love interest. Works like Stephenie Meyer’s “Twilight” series (2005-2008) and the television show “True Blood” (2008-2014) depicted vampires as brooding, misunderstood outsiders who struggled to control their predatory instincts and find acceptance in human society (Wilson, 2011). This romanticization of the vampire reflected changing attitudes towards sexuality, gender roles, and the nature of relationships in contemporary Western culture (Kane, 2010).

At the same time, the vampire continued to serve as a vehicle for social commentary and satire. Films like “Blade” (1998) and “Underworld” (2003) used the vampire mythos to explore themes of race, class, and power, while comedic works like “What We Do in the Shadows” (2014) parodied vampire tropes to humorous effect.

The vampire is a remarkably versatile and enduring figure that has captured the human imagination for centuries. From its roots in ancient mythology and folklore to its evolution in literature and popular culture, the vampire has served as a potent symbol through which societies have grappled with fundamental questions about the nature of life, death, desire, and social order.

By tracing the vampire’s cultural history and examining its symbolic significance through an anthropological lens, we can gain valuable insights into how different societies across time and space have understood and negotiated these core aspects of the human experience.

As the vampire continues to evolve and adapt in response to changing cultural attitudes and anxieties, it remains an essential part of our collective cultural heritage, reflecting both the darkest fears and the deepest yearnings of the human psyche.

Bibliography

Abbott, S. (2006). Celluloid vampires: Life after death in the modern world. University of Texas Press. Asma, S. T. (2009). On monsters: An unnatural history of our worst fears. Oxford University Press. Auerbach, N. (1995). Our vampires, ourselves. University of Chicago Press. Barber, P. (1988). Vampires, burial, and death: Folklore and reality. Yale University Press. Beresford, M. (2008). From demons to Dracula: The creation of the modern vampire myth. Reaktion Books. Borrini, M. (2014). Vampires: Between myth and reality. McFarland & Company. Butler, E. (2010). Metamorphoses of the vampire in literature and film: Cultural transformations in Europe, 1732-1933. Camden House. Chiang, W.-T., & Chiang, S.-C. (2007). The reinterpretation of Chinese vampire culture. Journal of Textual Criticism, 2(1), 102-122. Cohen, J. J. (Ed.). (1996). Monster theory: Reading culture. University of Minnesota Press. Copper, B. (1973). The vampire in legend, fact and art. Robert Hale & Company. Craft, C. (1984). “Kiss me with those red lips”: Gender and inversion in Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Representations, 8, 107-133. Curran, B. (2005). Vampires: A field guide to the creatures that stalk the night. New Page Books. Davies, O. (2003). The haunted: A social history of ghosts. Palgrave Macmillan. Dundes, A. (Ed.). (1998). The vampire: A casebook. University of Wisconsin Press. Frayling, C. (1991). Vampyres: Lord Byron to Count Dracula. Faber and Faber. Gelder, K. (1994). Reading the vampire. Routledge. Gordon, J., & Hollinger, V. (Eds.). (1997). Blood read: The vampire as metaphor in contemporary culture. University of Pennsylvania Press. Guiley, R. E. (2004). The encyclopedia of vampires, werewolves, and other monsters. Facts on File. Hallab, M. Y. (2009). Vampire god: The allure of the undead in Western culture. State University of New York Press. Hollinger, V. (1997). Fantasies of absence: The postmodern vampire. In J. Gordon & V. Hollinger (Eds.), Blood read: The vampire as metaphor in contemporary culture (pp. 199-212). University of Pennsylvania Press. Holte, J. C. (Ed.). (1997). The fantastic vampire: Studies in the children of the night. Greenwood Press. Hoppenstand, G., & Browne, R. B. (Eds.). (1996). The Gothic world of Anne Rice. Bowling Green State University Popular Press. Introvigne, M. (1997). The Gothic milieu: Black metal, Satanism, and vampires. In J. Gordon & V. Hollinger (Eds.), Blood read: The vampire as metaphor in contemporary culture (pp. 137-151). University of Pennsylvania Press. Jenkins, M. D. (2010). Vampire forensics: Uncovering the origins of an enduring legend. National Geographic Books. Kane, T. (2010). The changing vampire of film and television: A critical study of the growth of a genre. McFarland & Company. Keyworth, D. (2002). Troublesome corpses: Vampires and revenants from antiquity to the present. Desert Island Books. Konstantinos. (2010). Vampires: The occult truth. Llewellyn Publications. Krantz, J. (2011). Vampires: A bite-sized history. Allen & Unwin. Lecouteux, C. (2003). The secret history of vampires: Their multiple forms and hidden purposes. Inner Traditions. McClelland, B. A. (2006). Slayers and their vampires: A cultural history of killing the dead. University of Michigan Press. McNally, R. T., & Florescu, R. (1972). In search of Dracula: A true history of Dracula and vampire legends. New York Graphic Society. Melton, J. G. (2011). The vampire book: The encyclopedia of the undead. Visible Ink Press. Meyer, M. (1995). The vampire in African folklore and popular literature. Research in African Literatures, 26(3), 112-123. Miller, E. (Ed.). (2005). Vampires: Myths and metaphors of enduring evil. Inter-Disciplinary Press. Miller, M., & Taube, K. (1993). An illustrated dictionary of the gods and symbols of ancient Mexico and the Maya. Thames and Hudson. Moretti, F. (1997). Dialectic of fear. In J. Gordon & V. Hollinger (Eds.), Blood read: The vampire as metaphor in contemporary culture (pp. 7-16). University of Pennsylvania Press. Murgoci, A. (1926). The vampire in Roumania. Folklore, 37(4), 320-349. Noll, R. (Ed.). (1992). Vampires, werewolves, and demons: Twentieth century reports in the psychiatric literature. Brunner/Mazel. Overstreet, D. W. (2006). Not your mother’s vampire: Vampires in young adult fiction. Scarecrow Press. Perkowski, J. L. (1989). The Darkling: A treatise on Slavic vampirism. Slavica. Rickels, L. A. (1999). The vampire lectures. University of Minnesota Press. Roux, J.-P. (2007). Blut: Kunst, macht, politik und pathologie. Carl Hanser Verlag. Ramsland, K. (2002). The science of vampires. Berkley Boulevard Books. Rickels, L. A. (1999). The vampire lectures. University of Minnesota Press. Rowen, N. (Ed.). (2020). The Palgrave handbook of vampires and vampire studies. Palgrave Macmillan. Senf, C. A. (1998). Dracula: Between tradition and modernism. Twayne Publishers. South, M. (Ed.). (2015). Mythical creatures and the symbolic mythology. Guttenberg Press. Sterling, B. (1991). Vampires in the Lemon Grove. In D. Hartwell (Ed.), Year’s best fantasy and horror (Vol. 4, pp. 359-360). St. Martin’s Press. Summers, M. (1928). The vampire: His kith and kin. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Summers, M. (1929). The vampire in Europe. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Twitchell, J. B. (1981). The living dead: A study of the vampire in Romantic literature. Duke University Press. West, M. L. (1995). Immortal wishes: Vampires in ancient Greece and Rome. Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 109, 27-39. Weston, J. (2018). Vampires and other blood-sucking fiends. Rosen Publishing Group. Wilson, N. (2011). Seduced by Twilight: The allure and contradictory messages of the popular saga. McFarland & Company. Wynne, C. (2013). Bram Stoker, Dracula and the Victorian Gothic stage. Palgrave Macmillan.

0 Comments