Exploring Universal Patterns of Human Experience

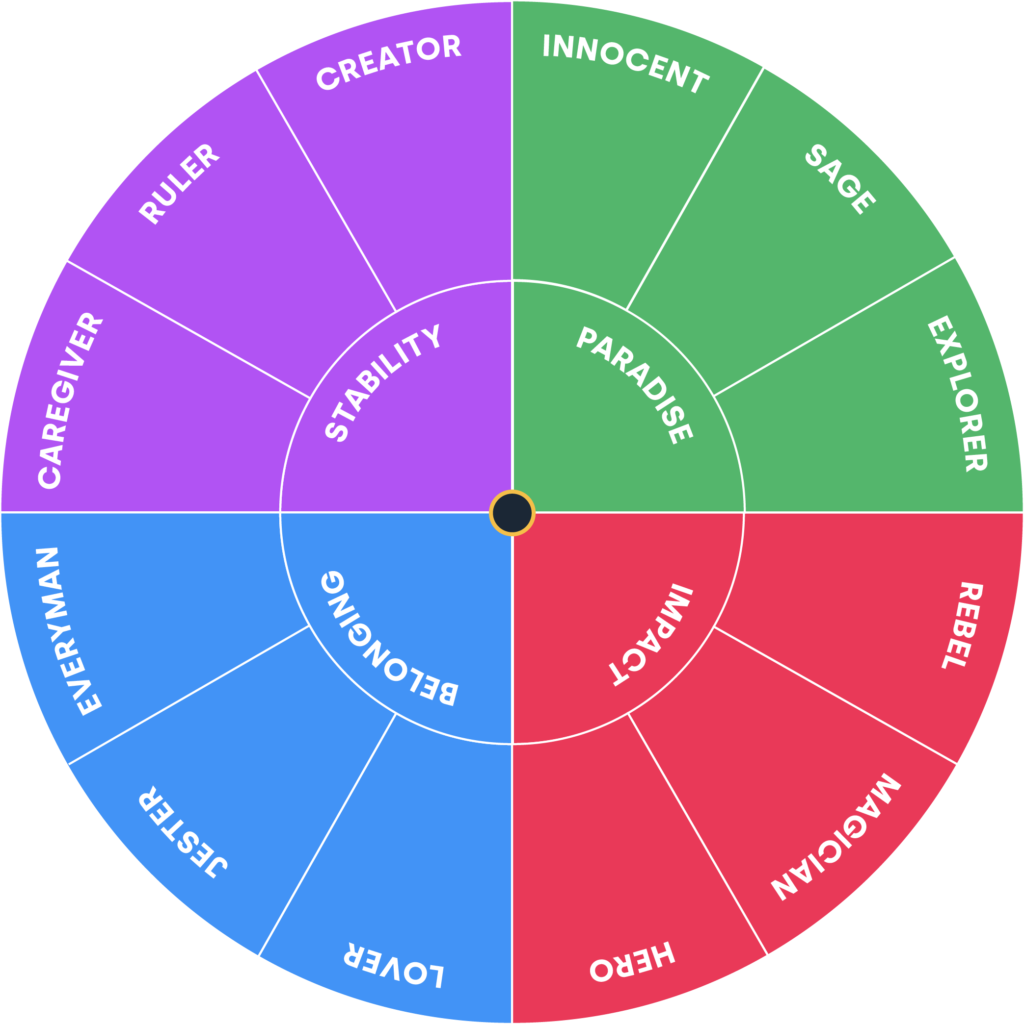

In the vast tapestry of human psychology, certain patterns emerge that seem to transcend culture, time, and individual experience. These universal themes, known as archetypes, were first identified by Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung as fundamental components of our collective unconscious (Jung, 1969). Today, we recognize 12 primary archetypes that shape our understanding of human behavior, storytelling, and personal growth (Pearson, 1991). Let’s explore each of these archetypes, their characteristics, and their significance in our lives and culture.

Explore all the Archetypes

The Hero: Courage, Determination, and the Quest for Meaning

The Hero archetype embodies the human drive to overcome obstacles, face challenges, and achieve greatness. Heroes are driven by a strong moral code and a desire to protect and serve others (Campbell, 1949). They often embark on transformative journeys, facing trials that test their mettle and ultimately lead to personal growth and the betterment of their community.

Examples in Culture:

- Hercules in Greek mythology

- Luke Skywalker in Star Wars (Lucas, 1977)

- Katniss Everdeen in The Hunger Games (Collins, 2008

Shadow Aspects: When unbalanced, the Hero can become arrogant, reckless, or develop a martyr complex (Pearson, 1991).

The Magician: Transformation, Wisdom, and the Power of Knowledge

The Magician archetype represents the power of knowledge, transformation, and the ability to bridge the gap between the mundane and the divine. Magicians are seekers of wisdom and masters of hidden knowledge, using their skills to facilitate change and growth in themselves and others (Jung, 1969).

Examples in Culture:

- Merlin in Arthurian legends (Matthews, 2004)

- Gandalf in The Lord of the Rings (Tolkien, 1954)

- Hermione Granger in Harry Potter (Rowling, 1997)

Shadow Aspects: The shadow Magician can become manipulative, using knowledge for personal gain or to deceive others (Pearson, 1991).

The Outlaw: Rebellion, Revolution, and the Challenge to Authority

The Outlaw archetype embodies the spirit of rebellion and the desire to challenge established norms and structures. Outlaws question authority, push boundaries, and often catalyze social change through their unconventional actions and perspectives (Pearson, 1991).

Examples in Culture:

- Robin Hood (Pyle, 1883)

- V in V for Vendetta (Moore & Lloyd, 1988)

- Starbuck in Battlestar Galactica (Moore, 2004)

Shadow Aspects: Unbalanced Outlaws may become destructive, antisocial, or engage in criminal behavior without regard for consequences (Pearson, 1991).

The Sage: Wisdom, Knowledge, and the Search for Truth

The Sage archetype represents the pursuit of knowledge, understanding, and truth. Sages are driven by a deep desire to comprehend the world around them and share their wisdom with others (Jung, 1969). They often serve as mentors, teachers, and advisors, guiding others on their own paths of growth and self-discovery.

Examples in Culture:

- Socrates (Plato, 399 BCE)

- Yoda in Star Wars (Lucas, 1980)

- Professor Dumbledore in Harry Potter (Rowling, 1997)

Shadow Aspects: The shadow Sage can become dogmatic, rigid in their thinking, or withhold knowledge for personal power (Pearson, 1991).

The Caregiver: Compassion, Nurturing, and Unconditional Love

The Caregiver archetype embodies the qualities of compassion, empathy, and the desire to nurture and protect others. Caregivers are driven by a deep sense of responsibility and a need to alleviate suffering in the world around them (Pearson, 1991).

Examples in Culture:

- Mother Teresa (Spink, 1997)

- Nurse Joy in Pokémon (Tajiri, 1996)

- Molly Weasley in Harry Potter (Rowling, 1997)

Shadow Aspects: Unbalanced Caregivers may become codependent, enabling unhealthy behaviors, or neglecting their own needs (Pearson, 1991).

The Lover: Passion, Intimacy, and the Search for Fulfillment

The Lover archetype represents the human desire for connection, intimacy, and passionate experience. Lovers are driven by a quest for beauty, sensual pleasure, and the ecstatic union of body, mind, and soul (Jung, 1969).

Examples in Culture:

- Romeo and Juliet (Shakespeare, 1597)

- Don Juan (Molière, 1665; Mozart, 1787)

- Jack and Rose in Titanic (Cameron, 1997)

Shadow Aspects: The shadow Lover can become obsessive, jealous, or engage in unhealthy or destructive relationships (Pearson, 1991).

The Jester: Humor, Mischief, and the Power of Laughter

The Jester archetype embodies the spirit of play, mischief, and the transformative power of humor. Jesters use wit, irony, and satire to challenge conventions, expose truths, and bring joy and laughter to the world (Pearson, 1991).

Examples in Culture:

- The Fool in Shakespeare’s plays (Shakespeare, 1623)

- Bugs Bunny (Avery, 1940)

- Deadpool (Nicieza & Liefeld, 1991)

Shadow Aspects: Unbalanced Jesters may become cruel, insensitive, or use humor to avoid facing serious issues (Pearson, 1991).

The Creator: Creativity, Innovation, and the Pursuit of Self-Expression

The Creator archetype represents the human drive to create, innovate, and express oneself through art, music, writing, or other forms of creative expression. Creators are driven by a deep need to manifest their unique vision and leave a lasting impact on the world (Jung, 1969).

Examples in Culture:

- Leonardo da Vinci (Kemp, 2019)

- Frida Kahlo (Herrera, 1983)

- Tony Stark (Iron Man) (Lee & Lieber, 1963)

Shadow Aspects: The shadow Creator can become self-absorbed, perfectionistic, or unable to complete projects (Pearson, 1991).

The Ruler: Leadership, Power, and the Pursuit of Order

The Ruler archetype embodies the qualities of leadership, authority, and the desire to create order and structure in the world. Rulers are driven by a sense of responsibility and a need to protect and guide their communities (Pearson, 1991).

Examples in Culture:

- Queen Elizabeth I (Somerset, 2003)

- Aragorn in The Lord of the Rings (Tolkien, 1955)

- Daenerys Targaryen in Game of Thrones (Martin, 1996)

Shadow Aspects: Unbalanced Rulers may become tyrannical, controlling, or abuse their power for personal gain (Pearson, 1991).

The Innocent: Purity, Trust, and the Quest for Paradise

The Innocent archetype represents the human desire for purity, goodness, and the belief in a better world. Innocents are characterized by their optimism, trust, and faith in the goodness of others and the universe (Pearson, 1991).

Examples in Culture:

- Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz (Baum, 1900)

- Forrest Gump (Groom, 1986; Zemeckis, 1994)

- SpongeBob SquarePants (Hillenburg, 1999)

Shadow Aspects: The shadow Innocent can become naive, gullible, or unable to face the realities of the world (Pearson, 1991).

The Explorer: Adventure, Discovery, and the Quest for New Horizons

The Explorer archetype represents the innate human desire to venture into the unknown, discover new lands and peoples, and expand the boundaries of knowledge and experience (Pearson, 1991). From ancient nomadic tribes to modern-day astronauts and deep-sea divers, the Explorer has been a driving force in the evolution of human culture and civilization.

Examples in Culture:

- Odysseus in Homer’s Odyssey (Homer, 8th century BCE)

- Marco Polo (Polo & Latham, 1958)

- Indiana Jones (Spielberg, 1981-2008)

Shadow Aspects: The shadow Explorer may become reckless, self-centered, or disregard the impact of their actions on others (Pearson, 1991).

Analysts and Archetypes

Many psychologists, therapists, and other analysts have drawn upon the archetypal framework in their work with clients and patients. Some notable examples include:

- James Hillman, a post-Jungian analyst, expanded on Jung’s ideas and developed Archetypal Psychology. He emphasized the importance of understanding the archetypes as autonomous forces that shape our lives and psyche (Hillman, 1975).

- Jean Shinoda Bolen, a Jungian analyst and psychiatrist, has written extensively on the archetypal patterns in women’s lives. In her books “Goddesses in Everywoman” and “Gods in Everyman,” she explores how mythological archetypes influence our personality development and life paths (Bolen, 1984, 1989).

- Carol Pearson, a psychologist and leadership consultant, has applied archetypal theory to the realm of personal growth and organizational development. Her book “Awakening the Heroes Within” outlines twelve archetypal patterns that individuals and organizations can use to navigate change and achieve their full potential (Pearson, 1991).

These analysts, among others, have used archetypes as a lens through which to understand their clients’ struggles, strengths, and paths to wholeness. By identifying the dominant archetypes in a person’s life, they can help them become more conscious of their patterns and work towards integrating the full spectrum of archetypal energies (Pearson, 1991).

Archetype Correlations with MBTI and Enneagram

While the 12 archetypes, MBTI (Myers-Briggs Type Indicator), and Enneagram are distinct systems, there are some interesting correlations and overlaps between them:

- The Hero archetype often correlates with MBTI types that have a strong sense of purpose and a desire to make an impact, such as ENTJ, ENFJ, INFJ, and ESTJ (Myers, 1962). In the Enneagram, the Hero is most closely associated with Types 1 (The Reformer), 3 (The Achiever), and 8 (The Challenger) (Riso & Hudson, 1996).

- The Sage archetype tends to correlate with introspective and analytical MBTI types, such as INTP, INTJ, INFJ, and INFP (Myers, 1962). In the Enneagram, the Sage resonates with Types 5 (The Investigator) and 9 (The Peacemaker) (Riso & Hudson, 1996).

- The Caregiver archetype often aligns with MBTI types that prioritize harmony and the needs of others, such as ESFJ, ISFJ, ENFJ, and INFP (Myers, 1962). In the Enneagram, the Caregiver is most strongly associated with Type 2 (The Helper) (Riso & Hudson, 1996).

It’s important to note that these correlations are not absolute, and an individual may embody multiple archetypes, MBTI preferences, and Enneagram types. The value in exploring these correlations lies in gaining a more multi-dimensional understanding of the human psyche and the various lenses through which we can understand ourselves and others (Pearson, 1991).

Somatic and Emotional Correlations of Archetype Repression and Over-Identification

When an archetype is repressed or over-identified with, it can manifest in various somatic (bodily) and emotional symptoms:

- Repression of the Hero archetype may lead to feelings of powerlessness, low self-esteem, and a lack of direction in life. Somatically, this may manifest as chronic fatigue, weakness, or a slouched posture (Pearson, 1991).

- Over-identification with the Outlaw archetype can result in chronic anger, defiance, and a sense of alienation from others. This may be accompanied by tension headaches, jaw clenching, or digestive issues (Pearson, 1991).

- Repression of the Lover archetype may lead to emotional numbness, difficulty forming intimate connections, and a sense of disconnection from one’s body and senses. This can manifest as sexual dysfunction, skin issues, or a lack of vitality (Pearson, 1991).

- Over-identification with the Caregiver archetype can result in burnout, resentment, and a loss of self. Somatic symptoms may include exhaustion, back pain (from “carrying” others’ burdens), or a weakened immune system (Pearson, 1991).

Cultivating a balanced relationship with the archetypes involves honoring their gifts while also acknowledging their shadows. Practices such as therapy, journaling, dream work, and somatic healing can help individuals reclaim disowned archetypal energies and learn to express them in healthy, conscious ways (Pearson, 1991). By embracing the full spectrum of the archetypes, we can tap into a greater sense of wholeness, resilience, and depth in our lives (Jung, 1969).

The Power of Archetypes

In conclusion, the 12 major archetypes offer a rich and nuanced framework for understanding the universal patterns that shape human experience. By exploring their characteristics, cultural expressions, and shadow aspects, we can gain valuable insights into our own psyche and the collective unconscious that connects us all (Jung, 1969). The work of analysts, the correlations with other personality systems, and the somatic and emotional dimensions of archetypal experience further highlight the depth and complexity of this powerful psychological model. Ultimately, engaging with the archetypes can be a transformative journey of self-discovery, growth, and the realization of our fullest potential (Pearson, 1991).

Bibliography

Avery, T. (Director). (1940). A Wild Hare [Film]. Warner Bros.

Baum, L. F. (1900). The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. George M. Hill Company.

Bolen, J. S. (1984). Goddesses in Everywoman: A New Psychology of Women. Harper & Row.

Bolen, J. S. (1989). Gods in Everyman: A New Psychology of Men’s Lives and Loves. Harper & Row.

Cameron, J. (Director). (1997). Titanic [Film]. Paramount Pictures; 20th Century Fox.

Campbell, J. (1949). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Pantheon Books.

Collins, S. (2008). The Hunger Games. Scholastic Press.

Groom, W. (1986). Forrest Gump. Doubleday.

Herrera, H. (1983). Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo. Harper & Row.

Hillenburg, S. (Creator). (1999). SpongeBob SquarePants [TV series]. Nickelodeon.

Hillman, J. (1975). Re-Visioning Psychology. Harper & Row.

Homer. (8th century BCE). The Odyssey.

Jung, C. G. (1969). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press.

Kemp, M. (2019). Leonardo da Vinci: The 100 Milestones. Sterling.

Lee, S., & Lieber, L. (1963). Tales of Suspense #39 [Comic book]. Marvel Comics.

Lucas, G. (Director). (1977). Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope [Film]. Lucasfilm; 20th Century Fox.

Lucas, G. (Director). (1980). Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back [Film]. Lucasfilm.

Martin, G. R. R. (1996). A Game of Thrones. Bantam Spectra.

Matthews, J. (2004). The Grail: Quest for the Eternal. Thames & Hudson.

Molière. (1665). Dom Juan ou le Festin de pierre.

Moore, A., & Lloyd, D. (1988). V for Vendetta. Vertigo.

Moore, R. D. (Developer). (2004-2009). Battlestar Galactica [TV series]. Sci-Fi Channel.

Mozart, W. A. (1787). Don Giovanni [Opera].

Myers, I. B. (1962). The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator: Manual. Consulting Psychologists Press.

Nicieza, F., & Liefeld, R. (1991). New Mutants #98 [Comic book]. Marvel Comics.

Pearson, C. S. (1991). Awakening the Heroes Within: Twelve Archetypes to Help Us Find Ourselves and Transform Our World. HarperCollins.

Plato. (399 BCE). The Apology of Socrates.

Polo, M., & Latham, R. (1958). The Travels of Marco Polo. Penguin Books.

Pyle, H. (1883). The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood. Scribner’s.

Riso, D. R., & Hudson, R. (1996). Personality Types: Using the Enneagram for Self-Discovery. Houghton Mifflin.

Rowling, J. K. (1997-2007). Harry Potter [Book series]. Bloomsbury.

Shakespeare, W. (1597). Romeo and Juliet.

Shakespeare, W. (1623). Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies (First Folio).

Somerset, A. (2003). Elizabeth I. Knopf.

Spielberg, S. (Director). (1981-2008). Indiana Jones [Film series]. Lucasfilm.

Spink, K. (1997). Mother Teresa: A Complete Authorized Biography. HarperCollins.

Tajiri, S. (Creator). (1996). Pokémon [TV series]. TV Tokyo.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954-1955). The Lord of the Rings. George Allen & Unwin.

Zemeckis, R. (Director). (1994). Forrest Gump [Film]. Paramount Pictures.

0 Comments