The Stages of Grief as Defelection from Existential Dread

We all go through the stages of grief all of the time:

The stages of grief – denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance – represent common emotional reactions to loss and change (Kübler-Ross & Kessler, 2005). However, they can also be seen as ways we deflect away from reality to pretend our interior emotional spaces can control external circumstances. In the depths of grief, we rage against what is, bargain for a different outcome, and sink into sorrow, before finally accepting what we cannot change (Pies, 2014). This process reveals core philosophical misconceptions that often surface in therapy – the belief that our thoughts and feelings can alter reality itself (Yalom, 1980).

These misconceptions are not just mental errors, but defense mechanisms against existential anxieties. We cling to the belief in an ultimate rescuer to avoid the dread of existential isolation (Yalom, 1980). We deny death to elude the reality of our own finitude (Becker, 1973). We imagine we are special and invulnerable to maintain an illusion of control in an unpredictable world (Pyszczynski, Greenberg, & Solomon, 1997). In therapy, recognizing and confronting these misconceptions is part of the journey toward self-actualization and authentic engagement with life (Rogers, 1995; May, 1981).

Let’s examine some of these core philosophical misconceptions in depth, tracing their roots in existential philosophy and psychology, and explore how they manifest in the therapeutic process.

Belief in an Ultimate Rescuer

One common misconception is the belief in an ultimate rescuer – a person, deity, or force that will save us from life’s hardships (Yalom, 1980). This stems from the existential anxiety of isolation, the recognition that we are fundamentally alone in our subjective experience. As infants, we rely on caregivers for survival, and this primal dependency can persist into adulthood as a yearning for a savior (Bowlby, 1969; Fromm, 1941). In therapy, this may manifest as a transference reaction, with the client viewing the therapist as an all-powerful figure who can magically resolve their problems (Freud, 1912). Part of the therapeutic process involves disillusionment from this fantasy and learning to face one’s aloneness with courage (Bugental, 1981).

The existential theologian Paul Tillich (1952) argued that the search for an ultimate rescuer is a form of idolatry, an attempt to make the finite infinite. We imbue a person or belief with absolute power to escape the anxiety of groundlessness. In therapy, clients may need to grieve the loss of this illusion and find meaning in self-reliance and human connection.

Death Denial

Another core misconception is death denial – the refusal to accept one’s own mortality. Ernest Becker (1973), in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book “The Denial of Death,” argued that humans are uniquely burdened by the knowledge of their finitude. Unlike other animals, we are aware that death is inevitable, and this existential terror underlies much of human behavior. We construct belief systems, strive for symbolic immortality through accomplishments, and invest in an afterlife to escape the reality of death (Becker, 1973).

In therapy, death denial can manifest as an avoidance of existential issues, a compulsive pursuit of success, or a paralyzing fear of the unknown (Yalom, 1980). Therapists may need to help clients confront their mortality, find meaning in the face of death, and live more fully in the present. The existential psychotherapist Irvin Yalom (2008) suggests that “though the physicality of death destroys us, the idea of death saves us” (p. 33). By accepting our finitude, we are motivated to seize the moment and craft a life of purpose.

The existential philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Heidegger both emphasized the centrality of death in human existence. For Heidegger, authentic being requires confronting one’s own mortality and the “being-toward-death” that defines the human condition. Sartre saw death as the ultimate limit to human freedom and meaning, arguing that we must create our own purpose in the face of this absurdity.

Belief in Personal Specialness or Invulnerability

A third misconception is the belief in personal specialness or invulnerability – the notion that we are exempt from life’s dangers and limitations (Yalom, 1980). This illusion of invincibility is a defense against the anxiety of uncertainty. If we imagine ourselves as special, we feel protected from random misfortunes that befall others.

The terror management theory in psychology proposes that self-esteem serves a protective function, shielding us from the fear of death (Pyszczynski, Greenberg, & Solomon, 1997). We cling to the belief that we are extraordinary and therefore immune to ordinary dangers. In therapy, this may present as narcissistic grandiosity, risk-taking behaviors, or a denial of one’s flaws and vulnerabilities (Yalom, 1980). The therapeutic task is to help clients develop a more realistic sense of self, accept their limitations with humility, and find courage in the face of life’s unpredictability.

The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche critiqued the human tendency toward self-inflation and the belief in one’s own specialness. In his concept of the “will to power,” Nietzsche saw a drive to overcome limitations and assert dominance that, when unchecked, could lead to narcissistic illusions of grandeur. His idea of the “übermensch” or “superman” who transcends ordinary human weaknesses was a cautionary tale about the dangers of believing oneself invulnerable.

The Jungian psychologist Jolande Jacobi connected this inflated sense of self to the archetype of the Hero. In myth, the hero often begins with a grandiose belief in their own invincibility, only to be brought low by tragedy and forced to confront their mortal limitations. The therapeutic process, like the hero’s journey, requires a surrendering of specialness and an acceptance of one’s ordinariness and vulnerability.

Illusion of Control

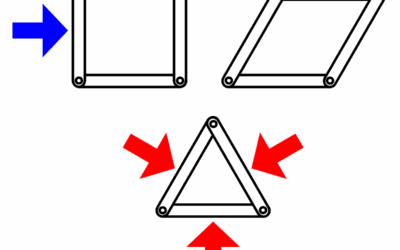

Related to specialness is the illusion of control – the belief that we can master external events through willpower or manipulation (Yalom, 1980). This misconception is a defense against the existential anxiety of groundlessness, the recognition that life is ultimately contingent and uncontrollable. We grasp at the illusion of control to feel secure in a chaotic world.

In therapy, this may manifest as perfectionism, obsessive-compulsive behaviors, or interpersonal power struggles (Shapiro, 1965). Clients may attempt to control the therapist, resist interventions, or blame external circumstances for their problems. The therapeutic challenge is to help clients relinquish the illusion of control, develop tolerance for uncertainty, and find peace in acceptance (Linehan, 1993).

The Serenity Prayer in Alcoholics Anonymous encapsulates this wisdom: “Grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference” (Niebuhr, 1943). By distinguishing between what is within our control and what is not, we can focus our energy on shaping our attitudes and actions, rather than fighting futile battles against reality.

The existential philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre famously declared that humans are “condemned to be free.” For Sartre, we are radically free to choose our actions and our way of being-in-the-world, but this freedom is a source of anguish because it comes with total responsibility. There is no ultimate control or meaning to our choices apart from what we make of them. Confronting this realization is the key to authentic living.

In analytical psychology, the illusion of control is often tied to an overreliance on the rational functions of the ego. As Marie-Louise von Franz suggests, the ego tends to believe it is the master of the psyche, when in reality it is only one part of a larger Self that includes uncontrollable unconscious and archetypal forces. Learning to relinquish egoic control and attune to the deeper wisdom of the unconscious is central to the process of individuation.

Meaninglessness

A fifth existential concern is meaninglessness – the worry that life has no inherent purpose or significance (Yalom, 1980). In the face of a vast, indifferent universe, our existence can feel arbitrary and absurd. This anxiety is captured in Albert Camus’ philosophical essay “The Myth of Sisyphus” (1942/1955), where he compares the human condition to the Greek myth of Sisyphus, condemned to roll a boulder up a hill for eternity.

In therapy, a sense of meaninglessness can manifest as apathy, depression, or suicidal ideation (Frankl, 1946/2006). Clients may feel that their lives are pointless, that their struggles are futile, or that their achievements are ultimately worthless. The therapeutic task is to help clients construct a sense of purpose, find value in their experiences, and engage in activities that generate meaning (Wong, 2010).

The psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl (1946/2006), in his influential book “Man’s Search for Meaning,” argued that meaning is not given but created. Even in the direst circumstances, we have the freedom to choose our attitude and actions, and thereby create meaning in our lives. Frankl proposed that meaning can be found through creativity, love, or transcendence of suffering. By dedicating ourselves to a cause, nurturing connections, or finding redemption in adversity, we can imbue our existence with significance.

Many existential philosophers grappled with the apparent absurdity and meaninglessness of life in an indifferent universe. Friedrich Nietzsche famously proclaimed the “death of God,” arguing that the decline of religious belief had left a terrifying vacuum of meaning that humans must fill with their own values and purpose. Jean-Paul Sartre similarly believed that existence precedes essence, and that we must create our own meaning through our choices and actions in a groundless world.

In Jungian psychology, the search for meaning is conceived as the drive to wholeness and self-realization. As Edward Edinger suggests, the Self is the ordering and unifying center of the psyche that guides the process of individuation. Experiences of meaninglessness signal an alienation from this deeper source of purpose and direction. The task of therapy, from this view, is to help the ego align with the Self, listen to the messages of the unconscious, and find an individual path of meaning.

Existential Isolation

A sixth misconception is the denial of existential isolation – the ultimate aloneness of our subjective experience (Yalom, 1980). Though we are embedded in social networks, we are fundamentally separate beings, each inhabiting our own consciousness. This isolation can evoke feelings of loneliness, alienation, and disconnection.

In therapy, a fear of isolation may present as codependent relationships, a need for constant validation, or a dread of abandonment (Yalom, 1980). Clients may avoid solitude, cling to unhealthy attachments, or conform to others’ expectations to preserve a sense of belonging. The therapeutic challenge is to help clients develop the capacity for autonomous functioning, tolerate aloneness, and cultivate authentic intimacy (Erikson, 1950).

The existential psychologist Rollo May (1953), in his book “Man’s Search for Himself,” proposed that the courage to be oneself, despite isolation, is the foundation of mental health. By embracing our individuality, asserting our will, and accepting the risks of authentic engagement, we can transform isolation into solitude and alienation into autonomy.

Many existential philosophers grappled with the apparent absurdity and meaninglessness of life in an indifferent universe. Friedrich Nietzsche famously proclaimed the “death of God,” arguing that the decline of religious belief had left a terrifying vacuum of meaning that humans must fill with their own values and purpose. Jean-Paul Sartre similarly believed that existence precedes essence, and that we must create our own meaning through our choices and actions in a groundless world.

In Jungian psychology, the search for meaning is conceived as the drive to wholeness and self-realization. As Edward Edinger suggests, the Self is the ordering and unifying center of the psyche that guides the process of individuation. Experiences of meaninglessness signal an alienation from this deeper source of purpose and direction. The task of therapy, from this view, is to help the ego align with the Self, listen to the messages of the unconscious, and find an individual path of meaning.

Freedom and Responsibility

A seventh existential concern is the burden of freedom and responsibility (Yalom, 1980). As autonomous beings, we are fundamentally free to choose our actions and attitudes, and therefore responsible for the consequences of our choices. This freedom can evoke anxiety, as it means that we must continually decide how to live and who to be.

In therapy, a denial of freedom may manifest as a victim mentality, an external locus of control, or a reliance on rigid rules and roles (Shapiro & Astin, 1998). Clients may attribute their problems to outside forces, follow prescribed scripts for living, or avoid making decisions to escape the anxiety of choice. The therapeutic task is to help clients recognize their agency, take ownership of their lives, and develop the courage to make authentic choices (Bugental, 1981).

Existential thinkers placed freedom and responsibility at the heart of the human condition. For Jean-Paul Sartre, we are “condemned to be free” – thrown into an absurd world without inherent meaning, we must continually define ourselves through our choices. This radical freedom is a source of anguish, as it comes with ultimate responsibility for our lives. Friedrich Nietzsche similarly believed that embracing the “will to power,” or drive to creatively shape one’s life, was essential to overcoming nihilism and affirming existence.

In Jungian psychology, freedom and responsibility are inherent in the process of individuation. As Marie-Louise von Franz suggests, individuation requires making the unconscious conscious – confronting shadow aspects of the psyche, wrestling with archetypal forces, and taking responsibility for the unique path of one’s life.

Avoidance of Autonomous Behavior

An eighth misconception is the avoidance of autonomous behavior – the reluctance to take independent action and assert one’s will (Yalom, 1980). This avoidance stems from the anxiety of freedom, the fear of making wrong choices and bearing the consequences. It can lead to a passive, dependent stance, where one defers to others’ opinions and expectations.

In therapy, this may present as difficulty making decisions, a fear of asserting needs, or a tendency to seek guidance for every dilemma (Shapiro & Astin, 1998). Clients may feel paralyzed by choices, doubt their own judgment, or fear disapproval for expressing their true thoughts and feelings. The therapeutic challenge is to foster autonomy, build self-trust, and encourage clients to experiment with independent action (Rogers, 1961).

The humanistic psychologist Carl Rogers (1961), in his book “On Becoming a Person,” proposed that autonomous functioning is a key characteristic of psychological health. As we learn to trust our experiences, express our feelings congruently, and act on our values consistently, we become more fully ourselves. By supporting clients’ self-determination and respecting their capacity for growth, therapists can create the conditions for autonomous flourishing.

Belief in Cosmic Meaning (vs. Terrestrial Meaning)

A ninth existential concern is the belief in cosmic meaning – the idea that life has an ultimate, ordained purpose that transcends our earthly existence (Yalom, 1980). This belief can provide comfort in the face of life’s transience and tragedies, but it can also breed passivity and disengagement from worldly concerns.

In therapy, a fixation on cosmic meaning may manifest as a preoccupation with destiny, a reliance on faith for solutions, or a deferral of responsibility to higher powers (Schoepflin, 2009). Clients may feel that their lives are divinely scripted, that their problems will be mystically resolved, or that their actions are inconsequential compared to cosmic forces. The therapeutic task is to help clients find terrestrial meaning, value their agency, and engage purposefully with the world at hand (Yalom, 1980).

The existential philosopher Martin Buber (1923/1958), in his book “I and Thou,” distinguished between two modes of relating: I-It, where we treat others as objects to be used, and I-Thou, where we meet others in their full humanity. Buber argued that meaning is found not in cosmic abstractions, but in the concrete, lived dialogue between beings. By engaging with the world and others as a whole, present self, we can infuse our lives with terrestrial significance.

Fear of Groundlessness

A tenth misconception is the fear of groundlessness – the anxiety that arises when we recognize the contingency and unpredictability of existence (Yalom, 1980). In the absence of a stable, absolute foundation, we can feel disoriented, unsure of what to believe or how to act. This groundlessness can evoke feelings of vertigo, nihilism, or existential angst.

In therapy, a fear of groundlessness may present as a clinging to certainty, a dogmatic adherence to beliefs, or a desperate search for meaning (Cooper, 2003). Clients may resist ambiguity, seek definitive answers, or adopt rigid worldviews to anchor their existence. The therapeutic challenge is to help clients tolerate uncertainty, embrace the fluidity of meaning, and cultivate resilience in the face of change (Schneider & May, 1995).

Existential philosophers grappled with the apparent groundlessness and absurdity of human existence in a universe without inherent meaning or stability. Friedrich Nietzsche proclaimed the “death of God” and the collapse of traditional morality, confronting the terrifying groundlessness that results. For Nietzsche, embracing this groundlessness is the key to liberation and self-creation. Martin Heidegger‘s concept of “thrownness” suggests that we are always already thrown into a world of contingency and uncertainty, without any ultimate ground or justification for our existence. Authenticity involves embracing this groundlessness and choosing to create meaning in the face of it.

As Marie-Louise von Franz suggests, engaging with the unconscious involves a confrontation with the groundless, the dissolution of certainties, and the fluid nature of psychic reality. The goal is not to eliminate groundlessness, but to develop a more flexible and open stance toward it.

The existential psychologist Kirk Schneider (1990), in his book “The Paradoxical Self,” proposed that mental health involves the capacity to hold opposites in tension, to embody both constancy and change. By learning to navigate the polarities of existence – freedom and limitation, isolation and connection, meaning and absurdity – we can develop a more flexible, adaptive self. Therapy can provide a safe space to explore these tensions, build tolerance for ambiguity, and find stability in the midst of groundlessness (Schneider & May, 1995).

Denial of Contingency in Life

An eleventh existential concern is the denial of contingency in life – the refusal to accept the randomness and unpredictability of events (Yalom, 1980). We often cling to the belief that life follows a predictable, controllable course, and that our actions can guarantee specific outcomes. This denial can breed a false sense of security and a blindness to possibility.

In therapy, a denial of contingency may manifest as an overreliance on plans, a difficulty adapting to change, or an intolerance for risk (Shapiro & Astin, 1998). Clients may adhere rigidly to routines, fear deviating from expectations, or feel shattered when life takes unexpected turns. The therapeutic task is to help clients embrace uncertainty, cultivate flexibility, and find meaning in the face of life’s surprises (Bugental, 1981).

The existential psychologist James Bugental (1976), in his book “The Search for Existential Identity,” argued that authenticity involves an openness to experience, a willingness to engage with novelty and possibility. By learning to welcome the unknown, take risks, and adapt to changing circumstances, we can live more fully and creatively.

Existential philosophers emphasized the radical contingency and unpredictability of human existence. For Jean-Paul Sartre, we are “condemned to be free” in a world without inherent structure or necessity. Our essence is not predetermined but emerges through our choices in a field of infinite possibilities. Martin Heidegger‘s concept of “thrownness” suggests that we are always already thrown into a world we did not choose, in circumstances beyond our control. Authentic being requires accepting this thrownness and embracing the possibilities that arise from our particular situation.

Jungian psychology likewise emphasizes the unpredictable and uncontrollable aspects of psychic life. For Carl Jung, the unconscious is not merely a repository of repressed material, but a living, creative matrix that constantly generates new forms and possibilities. As Marie-Louise von Franz suggests, engaging with the unconscious requires a surrendering of ego control and a willingness to be surprised and transformed by what emerges. Dreams, synchronicities, and creative breakthroughs often arrive unbidden, disrupting our plans and challenging our assumptions. The task of individuation involves learning to live in dialogue with these contingent and unpredictable forces.

Overidentification with Roles

A twelfth existential concern is the overidentification with roles – the tendency to define oneself narrowly in terms of social positions and expectations (Yalom, 1980). While roles can provide a sense of structure and belonging, they can also limit our sense of self and constrain our possibilities. When we identify too rigidly with a role, we may neglect other aspects of our being and struggle when that role is threatened or lost.

In therapy, overidentification with roles may present as a difficulty tolerating retirement, a fear of changing careers, or an over-attachment to labels and titles (Shapiro & Astin, 1998). Clients may feel lost when a role is removed, struggle to assert needs that conflict with role expectations, or define their worth solely in terms of occupational success. The therapeutic challenge is to help clients dis-identify from limiting roles, explore multiple facets of self, and base their worth on intrinsic qualities (Rogers, 1961).

The humanistic psychologist Abraham Maslow (1968), in his theory of self-actualization, proposed that psychological health involves a transcendence of narrow identities and a realization of one’s full potential. By learning to embrace our complexities, question societal prescriptions, and ground our worth in our inherent humanity, we can develop a more expansive, authentic sense of self.Existential philosophers warned against the dangers of losing oneself in socially prescribed identities and roles.

For Jean-Paul Sartre, this is a form of “bad faith” – a flight from the anguish of freedom into prefabricated essences. We cling to ready-made identities as a way of avoiding the responsibility of self-creation. Martin Heidegger‘s concept of “das Man” or “the they” similarly describes the lostness of the self in the average, anonymous attitudes and behaviors of the crowd. Authenticity involves differentiating from these collective neuroses and identifying and confronting ones own to discover the self.

Belief in the Curative Power of Insight Alone

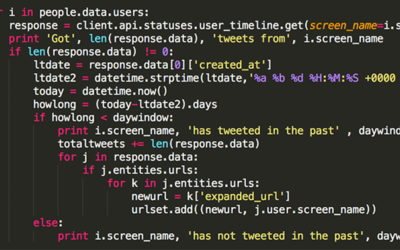

A thirteenth misconception is the belief in the curative power of insight alone – the idea that understanding the roots of one’s problems is sufficient for change (Yalom, 1980). While insight is an important component of therapy, it is not a panacea. Change also requires the cultivation of new behaviors, the practice of new skills, and the willingness to confront challenges in reality.

In therapy, an overemphasis on insight may manifest as a preoccupation with self-analysis, a reluctance to take concrete actions, or a belief that change will occur magically once underlying issues are uncovered (Yalom, 2002). Clients may spend years exploring their psyche, gain remarkable self-understanding, yet remain stuck in maladaptive patterns. The therapeutic task is to help clients translate insight into action, develop practical strategies for change, and build resilience through gradual behavioral shifts (Beck, 1979).

The cognitive therapist Aaron Beck (1979), in his book “Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders,” emphasized the importance of “collaborative empiricism” the process of working with clients to test beliefs in reality and modify thoughts and behaviors accordingly. By encouraging clients to take risks, try new approaches, and evaluate results, therapists can foster a sense of self-efficacy and promote lasting change.

The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle distinguished between theoretical and practical wisdom, arguing that true understanding must be translated into virtuous action. For Aristotle, the highest human good is not purely contemplative, but involves the active realization of one’s potential in the world. This emphasis on the unity of thought and action was echoed by existential philosophers like Jean-Paul Sartre, who argued that authenticity requires a courageous engagement with the world, not merely a detached, intellectual understanding.

In psychology, the action-oriented approach of behaviorism, as represented by thinkers like B.F. Skinner, challenged the insight-oriented depth psychology of Sigmund Freud and others. Skinner emphasized the primacy of observable behavior and the importance of reinforcement in shaping change, rather than the excavation of unconscious dynamics. More recently, cognitive-behavioral therapists like Aaron Beck and Albert Ellis have sought to integrate insight and action, helping clients to identify and challenge maladaptive thoughts and beliefs while also engaging in new, more adaptive behaviors.

Misconception that Life Should Be Fair

A fourteenth existential concern is the misconception that life should be fair – the belief that good deeds should be rewarded, that suffering should be proportionate to sins, and that the world should operate according to principles of justice (Yalom, 1980). This belief can create a sense of entitlement, a resentment toward adversity, and a struggle to accept life’s inequities.

In therapy, a fixation on fairness may present as a difficulty accepting losses, a preoccupation with others’ advantages, or a sense of righteous indignation when expectations aren’t met (Smedes, 1984). Clients may feel cheated by challenges, compare their lot to others’, or rage against the unfairness of their circumstances. The therapeutic task is to help clients accept the inherent unfairness of life, find meaning in adversity, and take responsibility for their choices regardless of circumstances (Frankl, 1946/2006).

The Buddhist concept of “dukkha,” often translated as “suffering” or “unsatisfactoriness,” holds that pain is an inherent part of existence (Bodhi, 1984). By accepting the universality of suffering, letting go of attachment to specific outcomes, and meeting pain with compassion, we can reduce our anguish and find peace in the midst of life’s difficulties.

The question of how to reconcile the existence of a benevolent God with the reality of suffering and injustice has been a perennial challenge for theology. Thinkers like St. Augustine, St. Thomas Aquinas, and Gottfried Leibniz developed sophisticated “theodicies” or justifications for the existence of evil, arguing that suffering serves a greater good or is a necessary consequence of human free will. More recently, process theologians like Alfred North Whitehead have proposed a dipolar God who co-suffers with creation and works to lure the world toward greater harmony and beauty.

In Eastern traditions like Buddhism and Taoism, the inherent unfairness of life is often accepted as a starting point rather than a problem to be solved. The Buddha’s First Noble Truth is that life is “dukkha” – inherently unsatisfactory and permeated by suffering. The path to liberation involves accepting this reality, letting go of attachments and aversions, and cultivating equanimity and compassion in the face of life’s vicissitudes. Taoist thinkers likewise emphasize the importance of aligning oneself with the Tao or Way of nature, accepting the interplay of opposites (yin and yang), and cultivating a spirit of non-contention and inner tranquility.

Belief in the Possibility of Perfect Security

A fifteenth existential concern is the belief in the possibility of perfect security – the idea that we can create a life free from danger, loss, and uncertainty (Yalom, 1980). This belief can lead to restrictive attempts to control one’s environment, an avoidance of risks, and a sense of anxiety when safety is threatened.

In therapy, a preoccupation with security may manifest as phobias, obsessive rituals, or a constriction of activities (van Deurzen, 2012). Clients may avoid flying, social situations, or intimacy due to fear of harm or rejection. They may engage in excessive precautions, ruminate about potential dangers, or feel paralyzed by anxiety when facing the unknown. The therapeutic challenge is to help clients accept the inevitability of risk, build distress tolerance, and engage meaningfully with life despite uncertainty (Yalom, 1980).

The existential psychotherapist Emmy van Deurzen (2012), in her book “Existential Counselling & Psychotherapy in Practice,” suggests that the quest for security is futile, as life is inherently uncertain. By learning to embrace vulnerability, take calculated risks, and derive a sense of safety from within, clients can break free from the confines of excessive caution and engage more fully with possibility.

Existential philosophers have often emphasized the inherent insecurity and vulnerability of the human condition. For Martin Heidegger, authentic being involves embracing our “being-toward-death” – the recognition that our existence is finite and that we are always projecting ourselves into an uncertain future. Rather than fleeing into the false security of the “they” (das Man), Heidegger advocated resolutely facing the “uncanniness” (unheimlichkeit) of existence. Similarly, for Jean-Paul Sartre, the human condition is characterized by a radical insecurity, as we are perpetually threatened by the gaze and judgments of others and must continually recreate ourselves through our choices.

In the field of attachment theory, psychologists like John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth have explored how early experiences of security or insecurity with primary caregivers shape our lifelong patterns of relating. A secure attachment, characterized by a caregiver’s consistent responsiveness and attunement, allows the child to develop a sense of safety and trust that can be carried into adulthood. Insecure attachments, on the other hand, can lead to chronic feelings of anxiety, avoidance, or ambivalence in close relationships. The therapeutic task, from this perspective, is to help clients develop “earned security” by internalizing the therapist’s caring, consistent presence and gradually learning to tolerate vulnerability and uncertainty.

Avoidance of Self-Confrontation

A sixteenth existential concern is the avoidance of self-confrontation – the reluctance to honestly examine oneself, acknowledge weaknesses, and confront painful truths (Yalom, 1980). This avoidance can lead to a denial of problems, a projection of blame onto others, and a stagnation of growth.

In therapy, an avoidance of self-confrontation may present as a resistance to exploring certain topics, a defensiveness when challenged, or a difficulty accepting responsibility for one’s role in problems (Bugental, 1981). Clients may deflect questions, externalize causes, or engage in self-justifying narratives to protect a fragile sense of self. The therapeutic task is to help clients develop the courage to face themselves honestly, accept their flaws and limitations, and take ownership of their choices and impacts (Yalom, 1980).

The Gestalt therapist Fritz Perls (1969), in his book “Gestalt Therapy Verbatim,” emphasized the importance of “self-confrontation in the here and now.” By learning to stay present with one’s immediate experience, acknowledge and express one’s genuine feelings, and take responsibility for one’s actions, clients can break free from self-deception and develop a more authentic, integrated sense of self.

The problem of self-deception has been a concern of philosophers since ancient times. In Plato’s dialogue “The Apology,” Socrates famously declared that “the unexamined life is not worth living,” suggesting that self-knowledge and self-scrutiny are essential to a meaningful existence. This theme was taken up by existential philosophers like Friedrich Nietzsche and Jean-Paul Sartre, who emphasized the importance of authenticity and the dangers of self-deception or “bad faith.” For Sartre, bad faith involves a flight from the anguish of freedom into prefabricated roles and identities that allow us to evade responsibility for our choices.

In psychology, the concept of defense mechanisms, as developed by Sigmund Freud and his daughter Anna Freud, suggests that we often unconsciously employ strategies like denial, repression, and projection to avoid painful truths and maintain a cohesive sense of self. More recently, cognitive therapists like Aaron Beck have explored how automatic negative thoughts and core beliefs can lead to self-defeating patterns of behavior. The therapeutic task, from a cognitive perspective, is to help clients identify and challenge these distorted beliefs and develop more realistic and adaptive ways of thinking about themselves and the world.

Fear of Self-Actualization

A seventeenth existential concern is the fear of self-actualization – the anxiety that arises when we consider fulfilling our potential and living authentically (Yalom, 1980). While we may yearn for growth and self-realization, we may also fear the risks and responsibilities that come with embracing our possibilities.

In therapy, a fear of self-actualization may manifest as a self-sabotaging of success, a difficulty making commitments, or a sense of paralysis when faced with major life decisions (Maslow, 1968). Clients may undermine their achievements, resist taking definitive stands, or feel overwhelmed by the prospect of charting their own course. The therapeutic challenge is to help clients confront their fears, clarify their values, and find the courage to live in accordance with their authentic desires (Rogers, 1961).

The humanistic psychologist Carl Rogers (1961), in his book “On Becoming a Person,” argued that we have a natural tendency toward self-actualization, but that this tendency can be blocked by conditions of worth and fears of disapproval. By providing unconditional positive regard, empathic understanding, and a safe space for self-exploration, therapists can help clients reconnect with their organismic valuing process and pursue the path of authentic growth.

The humanistic psychologists Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers placed self-actualization at the pinnacle of human motivation and development. For Maslow, self-actualization represents the realization of one’s full potential, the expression of creativity, spontaneity, and inner directedness. Rogers similarly believed that humans have a natural tendency toward growth and self-enhancement, but that this tendency can be thwarted by external conditions of worth and the internalization of others’ expectations. The therapeutic task, for Rogers, is to provide a safe, accepting environment in which clients can reconnect with their authentic desires and values.

Existential thinkers like Rollo May and Paul Tillich emphasized the importance of courage in the face of existential anxiety. For May, the “courage to be” involves the willingness to confront uncertainty, accept responsibility for one’s choices, and risk the disapproval of others in the pursuit of authenticity. Tillich similarly argued that the “courage to be” is the essential human response to the threat of non-being or meaninglessness. This courage involves a willingness to affirm one’s essential self in the face of death, guilt, and condemnation. By cultivating this type of courage, individuals can overcome the fears that block self-actualization and live with greater vitality and purposefulness.

Denial of Finitude and Limitations

An eighteenth existential concern is the denial of finitude and limitations – the refusal to accept the realities of aging, illness, and death, and the inherent limitations of human existence (Yalom, 1980). This denial can lead to an overextension of energies, a neglect of self-care, and a struggle to find meaning in the face of inevitable decline.

In therapy, a denial of finitude may present as a relentless pursuit of achievements, a resistance to slowing down or asking for help, or a sense of shock when faced with health crises or the deaths of loved ones (Becker, 1973). Clients may push themselves past their limits, refuse to delegate tasks or acknowledge needs, or feel unprepared for the challenges of aging and loss. The therapeutic task is to help clients accept their mortal nature, grieve losses as they occur, and find value in the present moment despite the inevitability of death (Yalom, 2008).

The philosophical movement known as “transhumanism” reflects a contemporary manifestation of the denial of finitude (Bostrom, 2005). Transhumanists seek to transcend biological limitations through technological enhancements, with the ultimate goal of achieving immortality. While the desire to extend life is understandable, an excessive preoccupation with transcending limits can breed a neglect of pressing realities and a disconnect from the existential ground of being.

The awareness of mortality has been a central preoccupation of human thought and culture since ancient times. In the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the oldest surviving works of literature, the hero undertakes a quest for immortality after the death of his friend, only to learn that eternal life is the prerogative of the gods alone. This theme is echoed in later Greek myths like the story of Tithonus, whose request for immortality is granted, but without eternal youth, dooming him to an endless decay.

Philosophers have long grappled with the existential implications of mortality. For Socrates, the practice of philosophy was a preparation for death, a way of cultivating the soul’s detachment from the body and its worldly concerns. Stoic philosophers like Seneca and Marcus Aurelius emphasized the importance of memento mori (remembrance of death) as a way of focusing the mind on what is truly important and living each day as if it were one’s last. Martin Heidegger, in his magnum opus “Being and Time,” argued that the awareness of death is the key to authentic existence, as it individuates us and reveals the inherent finitude and contingency of our projects.

In the 20th century, the cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker, in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book “The Denial of Death,” argued that the fear of mortality underlies much of human behavior and culture. For Becker, self-esteem serves as a vital buffer against death anxiety, and cultural worldviews and immortality projects (like art, religion, and nationalism) function as symbolic attempts to transcend death. By understanding these defensive maneuvers, Becker believed, we could develop a more mature and courageous approach to life in the face of mortality.

Belief in Absolute Truths and Universal Laws

A nineteenth existential concern is the belief in absolute truths and universal laws – the idea that there are objective, unchanging principles that govern reality and dictate proper conduct (Yalom, 1980). While a sense of certainty and moral clarity can provide comfort, an inflexible adherence to absolutes can breed dogmatism, judgment, and a struggle to adapt to complexities.

In therapy, a fixation on absolutes may present as a rigid, black-and-white thinking style, a difficulty tolerating ambiguity or exceptions, or a tendency to apply universal standards to diverse situations (Kohlberg, 1981). Clients may engage in moral perfectionism, categorical judgments of self and others, or a compulsive need to follow rules and principles. The therapeutic challenge is to help clients develop cognitive flexibility, tolerate nuance and context, and find a personal sense of meaning that allows for exceptions and individual differences (Frankl, 1946/2006).

The question of whether there are absolute truths and universal laws has been a subject of philosophical debate since ancient times. Plato, in his theory of Forms, argued that there are eternal, unchanging ideas that exist independently of the material world and serve as the basis for all knowledge and value. This perspective was challenged by sophists like Protagoras, who famously declared that “man is the measure of all things,” suggesting a more relativistic and contextual view of truth.

In the modern era, the Enlightenment thinkers sought to establish a rational foundation for knowledge and morality based on universal principles accessible to all through reason. This project was critiqued by counter-Enlightenment thinkers like Johann Hamann and Friedrich Nietzsche, who emphasized the historical, linguistic, and perspectival nature of all truth claims. Nietzsche’s perspectivism held that there are no facts, only interpretations, and that knowledge is always tied to particular interests and modes of life.

In psychology, the tension between universal principles and contextual variation is reflected in the debate between nomothetic and idiographic approaches. Nomothetic research, as exemplified by trait theories like those of Gordon Allport and Hans Eysenck, seeks to establish general laws of personality that apply across individuals. Idiographic approaches, as developed by thinkers like Gordon Allport and Henry Murray, emphasize the unique, irreducible qualities of each individual and the importance of understanding psychological phenomena within their specific context. Most contemporary psychologists recognize the importance of both nomothetic and idiographic perspectives and seek to integrate them in their research and practice.

Avoidance of Authentic Engagement

A twentieth and final existential concern is the avoidance of authentic engagement – the reluctance to fully embrace and participate in one’s life, relationships, and experiences (Yalom, 1980). This avoidance can manifest as a detachment from one’s feelings, a superficiality in one’s connections, and a sense of going through the motions rather than being fully present.

In therapy, an avoidance of authentic engagement may present as a difficulty accessing or expressing emotions, a pattern of disengagement or withdrawal from relationships, or a sense of alienation from one’s own experiences (May, 1981). Clients may intellectualize problems, maintain a façade of composure, or feel a pervasive sense of emptiness or disconnection. The therapeutic task is to help clients develop the capacity for emotional honesty, genuine relating, and full participation in their lives (Bugental, 1981).

The existential psychotherapist James Bugental (1987), in his book “The Art of the Psychotherapist,” described presence as a fundamental therapeutic skill. By learning to bring one’s whole self into the therapeutic encounter, attend fully to the client’s experience, and communicate with authenticity and immediacy, therapists can model and invite a more engaged way of being. Ultimately, the path to a meaningful life involves a willingness to show up fully, risk vulnerability, and embrace the joys and sorrows of existence.

The core existential concerns and philosophical misconceptions discussed above represent common challenges in the human struggle for meaning and authenticity. While these concerns can generate significant anxiety and suffering, they also provide opportunities for growth and transformation. By confronting these misconceptions in therapy, clients can develop a more realistic, flexible, and courageous approach to life’s inherent difficulties.

Ultimately, the path to existential well-being involves a willingness to accept reality as it is, embrace the full range of human experience, and take responsibility for one’s choices and actions. By learning to tolerate uncertainty, find meaning in the present moment, and engage authentically with oneself and others, one can navigate the challenges of existence with greater resilience, purpose, and joy.

As therapists, our role is to provide a safe, supportive space for clients to explore these existential concerns, challenge limiting beliefs, and experiment with new ways of being. By offering empathy, insight, and practical guidance, we can help clients develop the awareness, skills, and courage needed to live more fully and authentically. Ultimately, the goal of existential therapy is not to eliminate anxiety or provide definitive answers, but to help clients develop the capacity to face the complexities of existence with openness, creativity, and a sense of meaning and purpose.

Existential philosophers have long been concerned with the problem of authenticity and engagement in a world that often feels absurd or meaningless. Jean-Paul Sartre, in his concept of “bad faith,” described the common human tendency to flee from the anguish of freedom into prefabricated roles and identities. Authentic existence, for Sartre, requires a courageous embracing of our radical freedom and a willingness to create ourselves through our choices and actions in the world.

Martin Heidegger similarly explored the inauthentic modes of being-in-the-world, such as absorption in the anonymous “they-self” and the distraction of idle chatter. Authentic being, for Heidegger, involves a resolute owning of one’s finitude and a mindful engagement with the immediate context of one’s life. It is a shift from a passive, derivative mode of existence to an active, self-directed one.

Humanistic psychologists like Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow emphasized the importance of authentic self-expression and self-actualization. For Rogers, authenticity involves a congruence between one’s inner experience and outer communication, a willingness to be transparently oneself in relationships. Maslow described self-actualizing individuals as having a more efficient perception of reality, an openness to experience, and a fuller absorption in the present moment.

Buddhist psychology, as articulated by teachers like Thich Nhat Hanh and Jon Kabat-Zinn, emphasizes the cultivation of mindful presence as an antidote to the alienation and distraction of modern life. Through practices like meditation and mindful living, individuals can learn to disentangle from habitual thought patterns, contact a more vivid and immediate sense of reality, and participate more fully in the unfolding moments of their lives. This quality of engaged presence is seen as essential for both individual well-being and authentic connection with others.

The Anthropology of the Existential and the Mystical

Rather than seeking to eliminate or resolve existential tensions, the task may be to develop the capacity to hold them with greater wisdom and equanimity. Practices like mindfulness meditation, as described by David Abram, can help us dis-identify from our cognitive constructs and contact a more primordial, pre-conceptual layer of embodied experience. Engaging with myths, poetry, and art can open up symbolic spaces for exploring existential questions without reducing them to literal propositions.

Depth psychologists like Carl Jung and James Hillman emphasized the importance of attending to the living symbols and images of the psyche as messengers of existential meaning. By dialoguing with the unconscious through practices like active imagination, we can cultivate a more fluid and poetic relationship to the mysteries of existence.

Existential philosophers like Martin Heidegger and Maurice Merleau-Ponty proposed that authenticity involves embracing the inherent ambiguity and uncertainty of the human condition. Rather than seeking definitive answers or absolute foundations, the task is to engage fully in the ongoing process of questioning and self-discovery. By learning to dwell in the tensions between freedom and finitude, immanence and transcendence, being and becoming, we can live with greater creativity, vitality, and openness to the unknown.

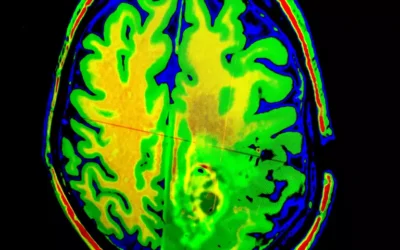

The Evolutionary and Neurobiological Roots of Existential Tensions

References

Beck, A. T. (1979). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. Penguin.

Becker, E. (1973). The denial of death. Free Press.

Bodhi, B. (1984). The noble eightfold path: The way to the end of suffering. Buddhist Publication Society.

Bostrom, N. (2005). Transhumanist values. Journal of Philosophical Research, 30(Supplement), 3-14.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Volume 1. Attachment. Basic Books.

Buber, M. (1958). I and thou (R. G. Smith, Trans.). Charles Scribner’s Sons. (Original work published 1923)

Bugental, J. F. T. (1976). The search for existential identity. Jossey-Bass.

Bugental, J. F. T. (1981). The search for authenticity: An existential-analytic approach to psychotherapy. Irvington.

Bugental, J. F. T. (1987). The art of the psychotherapist. W.W. Norton & Company.

Camus, A. (1955). The myth of Sisyphus and other essays. Alfred A. Knopf. (Original work published 1942)

Cavanna, A. E., & Trimble, M. R. (2006). The precuneus: A review of its functional anatomy and behavioural correlates. Brain, 129(3), 564-583.

Cooper, M. (2003). Existential therapies. SAGE Publications, Inc.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. W.W. Norton & Company.

Frankl, V. E. (2006). Man’s search for meaning. Beacon Press. (Original work published 1946)

Freud, S. (1912). The dynamics of transference. In J. Strachey (Ed. & Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 12, pp. 97-108). Hogarth Press.

Fromm, E. (1941). Escape from freedom. Farrar & Rinehart.

Kohlberg, L. (1981). Essays on moral development: Vol. 1. The philosophy of moral development. Harper & Row.

Kübler-Ross, E., & Kessler, D. (2005). On grief and grieving: Finding the meaning of grief through the five stages of loss. Scribner.

Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford Press.

Maslow, A. H. (1968). Toward a psychology of being (2nd ed.). Van Nostrand.

May, R. (1953). Man’s search for himself. W.W. Norton & Company.

May, R. (1981). Freedom and destiny. W.W. Norton & Company.

McGilchrist, I. (2009). The master and his emissary: The divided brain and the making of the Western world. Yale University Press.

Niebuhr, R. (1943). The serenity prayer. In E. Decker (Ed.), Prayers for self-help (p. 36). Harper & Brothers.

Nietzsche, F. (1966). Beyond good and evil: Prelude to a philosophy of the future (W. Kaufmann, Trans.). Random House. (Original work published 1886)

Perls, F. S. (1969). Gestalt therapy verbatim. Real People Press.

Pies, R. (2014). The bereavement exclusion and DSM-5: An update and commentary. Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience, 11(7-8), 19-22.

Pyszczynski, T., Greenberg, J., & Solomon, S. (1997). Why do we need what we need? A terror management perspective on the roots of human social motivation. Psychological Inquiry, 8(1), 1-20.

Rogers, C. R. (1961). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. Houghton Mifflin.

Rogers, C. R. (1995). A way of being. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Sartre, J. P. (1943). Being and nothingness: An essay on phenomenological ontology. Washington Square Press.

Schneider, K. J. (1990). The paradoxical self: Toward an understanding of our contradictory nature. Plenum Press.

Schneider, K. J., & May, R. (1995). The psychology of existence: An integrative, clinical perspective. McGraw-Hill.

Schoepflin, R. (2009). Christian science on trial: Religious healing in America. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Shapiro, D. H. (1965). Neurotic styles. Basic Books.

Shapiro, S. L., & Astin, J. A. (1998). Control therapy: An integrated approach to psychotherapy, health, and healing. John Wiley & Sons.

Smedes, L. B. (1984). Forgive and forget: Healing the hurts we don’t deserve. Harper & Row.

Thompson, E. (2007). Mind in life: Biology, phenomenology, and the sciences of mind. Harvard University Press.

Tillich, P. (1952). The courage to be. Yale University Press.

Van Deurzen, E. (2012). Existential counselling & psychotherapy in practice (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

Varela, F. J., Thompson, E., & Rosch, E. (1991). The embodied mind: Cognitive science and human experience. MIT Press.

Wong, P. T. P. (2010). Meaning therapy: An integrative and positive existential psychotherapy. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 40(2), 85-93.

Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential psychotherapy. Basic Books.

Yalom, I. D. (2002). The gift of therapy: An open letter to a new generation of therapists and their patients. HarperCollins.

Yalom, I. D. (2008). Staring at the sun: Overcoming the terror of death. Jossey-Bass.

0 Comments