Why do Humans Need Justice?

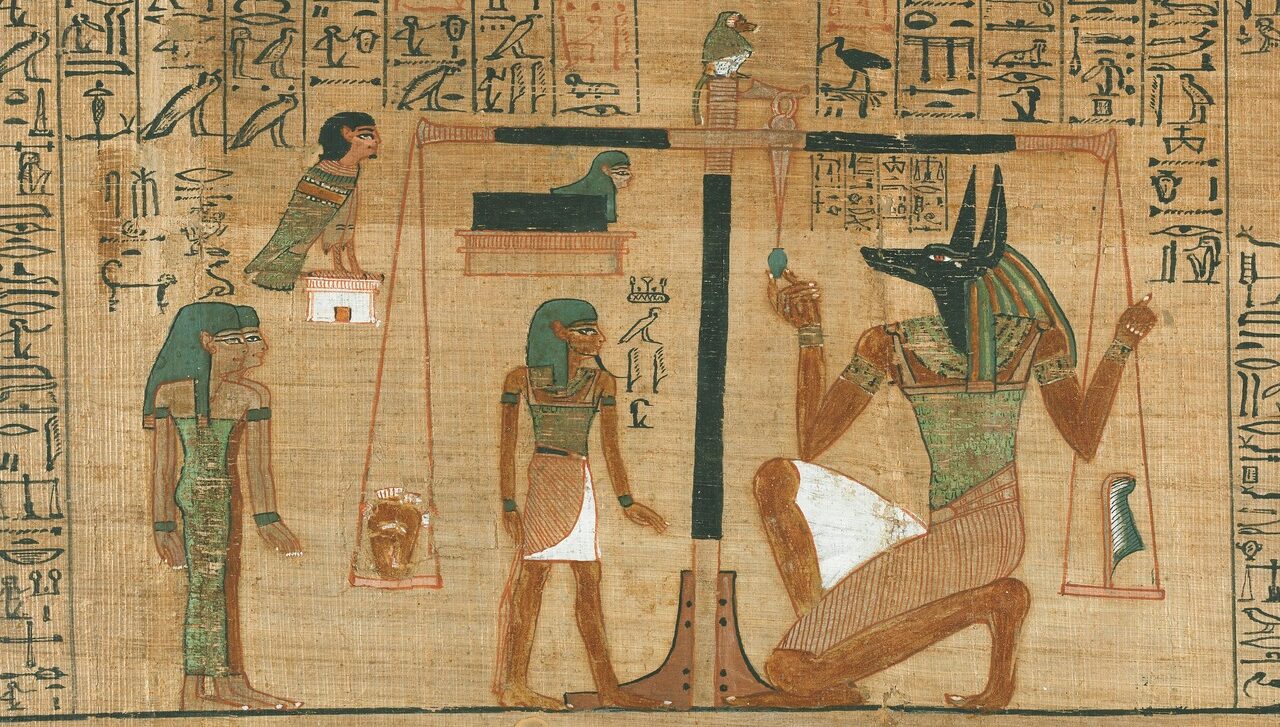

Anubis weighing the heart of the deceased’s soul against a feather in Egyptian myth

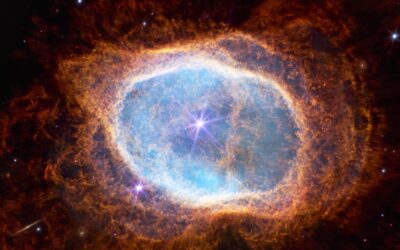

Our powerful instinct for fairness and justice is a key part of what makes us human. We expect rewards to match efforts, punishments to fit crimes, and people to be treated equally (Starmans et al., 2017). This drive for equity shapes our interpersonal relationships, social structures, political institutions, and legal frameworks (Fehr & Schmidt, 1999). But where does this deep-seated sense of fairness come from? Emerging insights from neuroscience, evolutionary psychology, and anthropology are revealing the biological roots of our most cherished social norms.

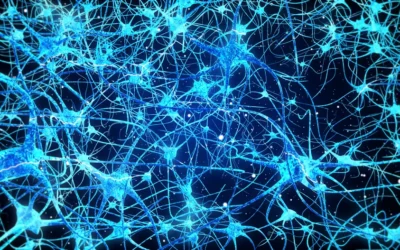

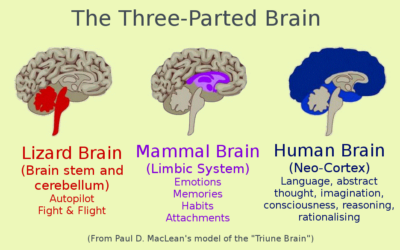

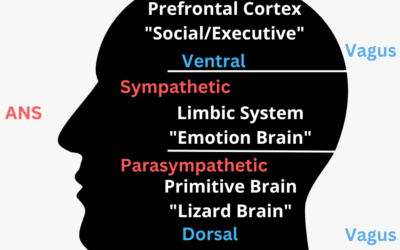

The Neural Circuitry of Fairness

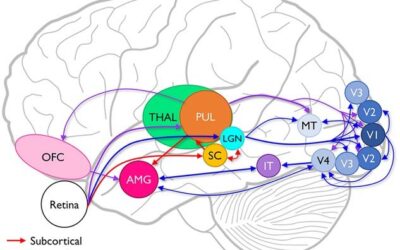

Advanced brain imaging is pulling back the curtain on the neural mechanisms underlying our fairness instinct. fMRI studies show that fairness and justice activate a network of brain regions evolved to process social information (Tabibnia et al., 2008). The insular cortex, which handles interoceptive awareness and emotions, fires in response to unequal distributions of rewards (Hsu et al., 2008). The amygdala, the brain’s “alarm system”, reacts strongly to violated fairness norms, while the reward-processing striatum encodes satisfaction with equitable outcomes (Tabibnia et al., 2008). Strikingly, fair treatment activates the same reward circuitry as receiving money, highlighting the intrinsic value we place on justice (Tabibnia et al., 2008).

The prefrontal cortex, responsible for higher-order reasoning, also plays a key role in judgments of fairness. Patients with prefrontal lesions are more likely to accept unfair offers in the Ultimatum Game, suggesting this region normally restrains our emotional aversion to injustice and guides rational decisions (Koenigs & Tranel, 2007). The precise prefrontal computations underlying fairness are a key area for further research.

Justice Instincts in Babies

Intriguingly, our sense of fairness emerges very early in development. In a seminal study, Hamlin et al. (2011) showed 15-month-old infants puppet shows where one character helped another climb a hill, while another puppet hindered the climber. When given a choice, over 80% of infants reached for the helpful puppet, suggesting an early preference for prosocial, cooperative behavior. This finding has since been replicated in multiple labs worldwide.

Schmidt & Sommerville (2011) further probed infants’ fairness expectations using a “violation of expectation” paradigm. 15-month-olds watched an experimenter distribute crackers either equally or unequally between two puppets. Infants looked significantly longer at the unequal outcome, a telltale sign that it violated their expectations. Critically, the infants’ gaze patterns suggest they expected equal payouts and were surprised by unfairness. However, this expectation of equality appears to be resource-specific at this age. In a follow-up by Sloane et al. (2012), 21-month-olds expected an experimenter to distribute edible rewards equally between two recipients, but not inedible items like rocks. By 3 years, children expect equal distributions of both resources and work efforts (Hamann et al., 2014).

Children’s fairness behaviors continue developing through early life. By around 7-8 years, kids playing the Ultimatum Game start showing an “irrational” rejection of unfair offers, even if this means getting nothing (Murnighan & Saxon, 1998). That is, they’re willing to pay a personal cost to punish selfishness. Younger kids tend to be more “rational” and accept all nonzero offers. The emergence of costly punishment with age may reflect increased inequity aversion (McAuliffe et al., 2013), the maturation of emotion regulation skills (Steinbeis & Singer, 2013), and internalization of social norms (Tomasello & Vaish, 2013).

Evolutionary Heritage

Humans’ sensitivity to unfairness is shared with other social primates, implying deep evolutionary roots. The Grape/Cucumber Test, pioneered with capuchin monkeys in a 2003 Science paper (Brosnan & de Waal, 2003), sheds light on these origins. Pairs of monkeys completed a simple task to receive a food reward – either a lesser-valued cucumber slice or a coveted grape. When the partners’ rewards were unequal (one cucumber, one grape), monkeys often rejected the inferior reward, sometimes hurling it back at the experimenter in apparent protest!

Since this landmark finding, inequity aversion has been documented in chimpanzees (Brosnan et al., 2005), bonobos (Bräuer et al., 2009), cotton-top tamarins (Freeman et al., 2013), dogs (Range et al., 2009), and ravens (Massen et al., 2015). Greater inequity aversion often appears when unequal pay is unrelated to effort or expertise (Brosnan et al., 2010). During tasks requiring cooperation, primates are less likely to collaborate with partners not pulling their weight (Melis et al., 2006), and even punish free-riders (Herrmann et al., 2008). Chimpanzees and bonobos playing the Ultimatum Game offer more equal splits than rational self-interest would predict (Jensen et al., 2007; Milinski, 2013). These homologies suggest a long evolutionary history to the human fairness instinct.

Several evolutionary pressures likely favored the emergence of fairness norms:

Cooperation:

A shared sense of fairness enables cooperation between unrelated individuals for mutual benefit. Groups that could build equitable, trusting relationships would outcompete less cooperative groups (Nowak & Sigmund, 2005).

Protection from exploitation:

An aversion to getting shortchanged defends against being taken advantage of by free-riders and cheaters (Price et al., 2002).

Costly punishment:

Punishing unfairness, even at a personal cost, deters would-be exploiters and enforces prosocial norms (Fehr & Gächter, 2002). In simulations, altruistic punishers who sanction injustice can outcompete pure cooperators (Bowles & Gintis, 2004).

Reputation building:

Known fairness yields reputational gains and makes one an attractive social partner (Barclay, 2011). Individuals prefer to interact and cooperate with those seen as just and equitable (Pfattheicher et al., 2016).

These evolutionary pressures would have made fairness instincts highly adaptive over human prehistory. Indeed, anthropological evidence from modern hunter-gatherers, the best models for ancestral human groups, attests to the central role of egalitarianism, food sharing, and sanctions for hoarding (Apicella et al., 2012; Cashdan, 1989). Violating fairness norms in these tight-knit groups, where reputations strongly impact biological fitness, would have been a losing strategy (Gintis, 2000). Thus, natural selection likely calibrated our minds to be acutely sensitive to justice.

Modern Manifestations

Humanity’s evolved preference for fairness exerts a powerful influence in the modern world. It shapes our interpersonal conduct, political philosophies, legal codes, and economic systems (Starmans et al., 2017). When norms of procedural and distributive justice are violated, individual relationships and societal institutions suffer (Tyler, 2000). Perceived unfairness provokes employee dissatisfaction, political unrest, and economic instability (Cowherd & Levine, 1992; Kahneman et al., 1986). Trust and cooperation break down. On the flip side, groups, organizations, and societies with strong fairness norms tend to enjoy superior cohesion and stability (Tyler & Blader, 2000).

Key Studies in Depth

- Dictator Game (Kahneman et al., 1986):

The Dictator Game, first conducted by Kahneman et al. in 1986, has become a classic experimental paradigm for probing prosocial preferences. In this game, one player (the dictator) is endowed with a sum of money and must decide how to split it between themselves and a passive recipient. According to rational choice theory, a self-interested dictator should offer nothing. But in practice, offers typically average 20-30% of the stake, with outright zero offers being quite rare (Camerer, 2003).

This is a striking finding, as the dictator has no economic incentive for sharing – the recipient cannot retaliate against stingy offers. The standard interpretation is that dictators are motivated by intrinsic preferences for fairness, altruism, and the warm glow of giving (Andreoni, 1990). However, subtle design details, such as the dictator and recipient being members of the same social group, can greatly impact giving (Whitt & Wilson, 2007). Methodological variations of the Dictator Game provide a flexible tool for isolating the various cognitive, affective, and contextual factors shaping human generosity.

- Ultimatum Game (Güth et al., 1982): A close cousin of the Dictator Game, the Ultimatum Game adds a crucial strategic wrinkle. The structure is similar – a proposer offers a split of an endowment to a responder. But now the responder can either accept the offer (in which case the proposed division occurs) or reject it (leaving both players with nothing). Rational choice theory predicts that responders should accept any nonzero amount, and proposers, anticipating this, should make the smallest possible offer. In reality, responders routinely reject offers below 20-30% of the stake, and proposers’ offers are substantially higher than the minimum, often reaching the 50/50 mark (Oosterbeek et al., 2004).

These results imply that responders are willing to pay a cost to punish offers perceived as unfair. The Ultimatum Game thus operationalizes the human tendency for altruistic punishment: penalizing norm violators even when it is costly to the self (Fehr & Gächter, 2002). Furthermore, it reveals that this fairness-seeking behavior is strong enough to shape others’ actions, leading proposers to make more equitable offers than pure self-interest would dictate. This game has been studied across diverse societies, revealing substantial cross-cultural commonalities in norms of fair division and reciprocal punishment (Henrich et al., 2005).

- Third-Party Punishment Game (Fehr & Fischbacher, 2004):

The Third-Party Punishment Game takes the logic of the Ultimatum Game a step further. It involves three players: an allocator (A) who divides an endowment between themselves and a recipient (B), and an observer (C) who witnesses this division. The twist is that C can spend some of their own endowment to punish A for making an unfair split. This design separates fairness concerns from personal involvement – C’s payoff isn’t affected by A’s allocation to B, but many Cs will still pay to punish A’s greed.

This experiment cleanly demonstrates humans’ willingness to enforce fairness norms even when they are not directly harmed by norm violations. Such third-party punishment is considered a key element in the stability of human prosocial norms (Fehr & Fischbacher, 2004). In most societies studied, a significant proportion of subjects punish selfishness directed at strangers, and the severity of punishment increases with the unfairness of the division (Bernhard et al., 2006; Henrich et al., 2006).

Interestingly, the prevalence and intensity of third-party punishment varies substantially across cultures, being stronger in large-scale, market-integrated societies (Henrich et al., 2006). This pattern dovetails with evolutionary theories proposing that third-party punishment is vital for preserving cooperation in large groups where reputational incentives are weak – the exact conditions that prevail in modern nation states, but not necessarily in small-scale societies (Marlowe et al., 2008).

- Capuchin Grape/Cucumber Test (Brosnan & de Waal, 2003):

In a pioneering comparative study published in Nature, Brosnan and de Waal (2003) set out to probe the evolutionary roots of the human aversion to unfairness. They devised a simple yet ingenious test of inequity aversion in brown capuchin monkeys. Pairs of monkeys had to complete a trivial task (handing a small rock to a human experimenter) to receive a food reward – either a low-value cucumber slice or a highly prized grape. When both monkeys received the same reward (cucumber or grape) for equal effort, exchanges proceeded smoothly. But when one monkey received a grape and the other a cucumber, the cucumber recipient often refused to accept the inferior reward, sometimes even throwing it back at the experimenter.

This finding was striking for two reasons. First, it suggested that monkeys, like humans, compare their own efforts and payoffs to those of others, protesting when these ratios are inconsistent. Second, it raised the possibility that the roots of inequity aversion – a central component of the human fairness sense – might extend far back in primate evolution. Subsequent work has both replicated and qualified this result. Monkeys’ rejections of inequity may depend more on the discrepancy in reward quality than on effort expended (Fontenot et al., 2007; van Wolkenten et al., 2007). Moreover, inequity aversion in monkeys appears to be mainly self-centered – they protest disadvantageous inequity (receiving a lesser reward) but not advantageous inequity (receiving a better reward) (Silberberg et al., 2009). Nonetheless, this research pioneered the comparative study of fairness across species, a key step in reconstructing the evolutionary history of human fairness norms.

- Inequity Aversion in Infants (Schmidt & Sommerville, 2011):

Our intuitions about fairness shape social behavior from a remarkably young age, as demonstrated by Schmidt and Sommerville (2011) in a clever study of 15-month-old infants. The experiment capitalized on the well-established “violation of expectancy” paradigm, which uses looking time as an index of surprise. Infants watched a video of an adult dividing a pile of crackers between two recipients. In the “equal” condition, the crackers were distributed evenly, two per recipient. In the “unequal” condition, the division was skewed, with one recipient getting three crackers and the other only one.

The key finding was that infants spent significantly more time looking at the unequal division, suggesting that it defied their expectations. Importantly, this effect wasn’t driven by a low-level preference for asymmetry – infants looked equally at the two outcomes when the crackers were simply placed on plates without recipients. Only when resources were divided between social partners did infants show an expectation of equality.

This study dovetails with a growing body of evidence that core aspects of fairness are operative from the beginning of life. Even young babies prefer agents who help rather than hinder others (Hamlin et al., 2007), expect rewards to be distributed equitably (Sloane et al., 2012), and favor those who act to rectify unfairness (Meristo & Surian, 2014). While the developmental origins of fairness norms remain debated, it’s clear that our moral intuitions arise early, before extensive socialization or reasoning about abstract principles. As such, this research supports the view of morality as a universal, evolved feature of the human mind.

- Children’s Costly Punishment (McAuliffe et al., 2015):

One of the hallmarks of human fairness is our willingness to impose costs on ourselves to punish selfishness in others. This altruistic punishment undergirds large-scale cooperation, deterring cheaters and free-riders. To probe the developmental emergence of this key behavior, McAuliffe et al. (2015) tested 5- and 6-year-old children in a novel “Costly Punishment Game.” Children were paired with a puppet partner to complete a task for reward tokens which could later be exchanged for prizes. On each trial, the experimenter divided 6 tokens between the child and puppet. The distributions were either equal (3:3) or skewed (4:2 or 5:1 in the puppet’s favor). The critical question was whether children would be willing to sacrifice one of their own tokens to reduce their partner’s payoff – an analog of adult altruistic punishment in economic games.

The key finding was that 6-year-olds, but not 5-year-olds, engaged in costly punishment. When the puppet received more than its fair share, 6-year-olds sacrificed a token to reduce the puppet’s payoff about 40% of the time. Importantly, this behavior was specifically triggered by unfairness – children rarely punished when the division was equal. Moreover, the probability of punishment increased with the degree of inequity. Children were about twice as likely to punish when the split was 5:1 as opposed to 4:2.

These results suggest that costly punishment emerges in early childhood and rapidly becomes attuned to contextual variables like the severity of fairness violations. The study also highlights the power of puppet studies for studying children’s fairness behaviors in controlled yet naturalistic settings. By allowing realistic social interactions while maintaining experimental control, puppet paradigms offer a promising complement to the stylized economic games used with adults.

More broadly, this experiment adds to the growing evidence that key components of fairness emerge long before adulthood. Far from being the product of protracted socialization, our taste for justice and our willingness to defend it appear to be early-emerging, deeply rooted features of human development. Of course, this doesn’t deny the important role of culture and learning in shaping the mature form of fairness norms. But it does suggest that such norms resonate with basic intuitions that arise naturally in the developing mind.

References

Andreoni, J. (1990). Impure altruism and donations to public goods: A theory of warm-glow giving. The Economic Journal, 100(401), 464-477.

Apicella, C. L., Marlowe, F. W., Fowler, J. H., & Christakis, N. A. (2012). Social networks and cooperation in hunter-gatherers. Nature, 481(7382), 497-501.

Barclay, P. (2011). Competitive helping increases with the size of biological markets and invades defection. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 281(1), 47–55.

Bernhard, H., Fischbacher, U., & Fehr, E. (2006). Parochial altruism in humans. Nature, 442(7105), 912-915.

Bowles, S., & Gintis, H. (2004). The evolution of strong reciprocity: cooperation in heterogeneous populations. Theoretical Population Biology, 65(1), 17-28.

Brosnan, S. F., & de Waal, F. B. (2003). Monkeys reject unequal pay. Nature, 425(6955), 297-299.

Brosnan, S. F., Schiff, H. C., & de Waal, F. B. (2005). Tolerance for inequity may increase with social closeness in chimpanzees. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 272(1560), 253-258.

Brosnan, S. F., Salwiczek, L., & Bshary, R. (2010). The interplay of cognition and cooperation. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 365(1553), 2699-2710.

Bräuer, J., Call, J., & Tomasello, M. (2009). Are apes inequity averse? New data on the token-exchange paradigm. American Journal of Primatology, 71(2), 175-181.

Camerer, C. F. (2003). Behavioral game theory: Experiments in strategic interaction. Princeton University Press.

Cashdan, E. A. (1989). Hunters and Gatherers: Economic Behavior in Bands. In Economic anthropology (pp. 21-48).

Cowherd, D. M., & Levine, D. I. (1992). Product quality and pay equity between lower-level employees and top management: An investigation of distributive justice theory. Administrative Science Quarterly, 302-320.

Fehr, E., & Gächter, S. (2002). Altruistic punishment in humans. Nature, 415(6868), 137-140.

Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2004). Third-party punishment and social norms. Evolution and human behavior, 25(2), 63-87.

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. M. (1999). A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. The quarterly journal of economics, 114(3), 817-868.

Fontenot, M. B., Watson, S. L., Roberts, K. A., & Miller, R. W. (2007). Effects of food preferences on token exchange and behavioural responses to inequality in tufted capuchin monkeys, Cebus apella. Animal Behaviour, 74(3), 487-496.

Freeman, H. D., Sullivan, J., Hopper, L. M., Talbot, C. F., Holmes, A. N., Schultz-Darken, N., … & Brosnan, S. F. (2013). Different responses to reward comparisons by three primate species. PloS one, 8(10), e76297.

Gintis, H. (2000). Strong reciprocity and human sociality. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 206(2), 169-179.

Güth, W., Schmittberger, R., & Schwarze, B. (1982). An experimental analysis of ultimatum bargaining. Journal of economic behavior & organization, 3(4), 367-388.

Hamann, K., Warneken, F., & Tomasello, M. (2014). Children’s developing commitments to joint goals. Child development, 85(1), 137-145.

Hamlin, J. K., Wynn, K., & Bloom, P. (2011). How infants and toddlers react to antisocial others. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences, 108(50), 19931-19936.

Hamlin, J. K., Wynn, K., & Bloom, P. (2007). Social evaluation by preverbal infants. Nature, 450(7169), 557-559.

Henrich, J., McElreath, R., Barr, A., Ensminger, J., Barrett, C., Bolyanatz, A., … & Ziker, J. (2006). Costly punishment across human societies. Science, 312(5781), 1767-1770.

Henrich, J., Boyd, R., Bowles, S., Camerer, C., Fehr, E., Gintis, H., & McElreath, R. (2005). “Economic man” in cross-cultural perspective: Behavioral experiments in 15 small-scale societies. Behavioral and brain sciences, 28(6), 795-815.

Herrmann, E., Call, J., Hernández-Lloreda, M. V., Hare, B., & Tomasello, M. (2008). Humans have evolved specialized skills of social cognition: The cultural intelligence hypothesis. Science, 317(5843), 1360-1366.

Hsu, M., Anen, C., & Quartz, S. R. (2008). The right and the good: distributive justice and neural encoding of equity and efficiency. Science, 320(5879), 1092-1095.

Jensen, K., Call, J., & Tomasello, M. (2007). Chimpanzees are rational maximizers in an ultimatum game. Science, 318(5847), 107-109.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. (1986). Fairness as a constraint on profit seeking: Entitlements in the market. The American economic review, 728-741.

Koenigs, M., & Tranel, D. (2007). Irrational economic decision-making after ventromedial prefrontal damage: evidence from the Ultimatum Game. Journal of Neuroscience, 27(4), 951-956.

Marlowe, F. W., Berbesque, J. C., Barr, A., Barrett, C., Bolyanatz, A., Cardenas, J. C., … & Tracer, D. (2008). More ‘altruistic’punishment in larger societies. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 275(1634), 587-592.

Massen, J. J., Van Den Berg, L. M., Spruijt, B. M., & Sterck, E. H. (2015). Inequity aversion in relation to effort and relationship quality in long-tailed Macaques (Macaca fascicularis). American journal of primatology, 77(3), 356-365.

McAuliffe, K., Jordan, J. J., & Warneken, F. (2015). Costly third-party punishment in young children. Cognition, 134, 1-10.

McAuliffe, K., Blake, P. R., Kim, G., Wrangham, R. W., & Warneken, F. (2013). Social influences on inequity aversion in children. PloS one, 8(12), e80966.

Melis, A. P., Hare, B., & Tomasello, M. (2006). Chimpanzees recruit the best collaborators. Science, 311(5765), 1297-1300.

Meristo, M., & Surian, L. (2014). Infants distinguish antisocial actions directed towards fair and unfair agents. PloS one, 9(10), e110553.

Milinski, M. (2013). Chimps play fair in the ultimatum game. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(6), 1978-1979.

Murnighan, J. K., & Saxon, M. S. (1998). Ultimatum bargaining by children and adults. Journal of Economic Psychology, 19(4), 415-445.

Nowak, M. A., & Sigmund, K. (2005). Evolution of indirect reciprocity. Nature, 437(7063), 1291-1298.

Oosterbeek, H., Sloof, R., & Van De Kuilen, G. (2004). Cultural differences in ultimatum game experiments: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Experimental economics, 7(2), 171-188.

Pfattheicher, S., Landhäußer, A., & Keller, J. (2014). Individual differences in antisocial punishment in public goods situations: The interplay of cortisol with testosterone and dominance. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 27(4), 340-348.

Price, M. E., Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (2002). Punitive sentiment as an anti-free rider psychological device. Evolution and Human Behavior, 23(3), 203-231.

Range, F., Horn, L., Viranyi, Z., & Huber, L. (2009). The absence of reward induces inequity aversion in dogs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(1), 340-345.

Schmidt, M. F., & Sommerville, J. A. (2011). Fairness expectations and altruistic sharing in 15-month-old human infants. PloS one, 6(10), e23223.

Silberberg, A., Crescimbene, L., Addessi, E., Anderson, J. R., & Visalberghi, E. (2009). Does inequity aversion depend on a frustration effect? A test with capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella). Animal cognition, 12(3), 505-509.

Sloane, S., Baillargeon, R., & Premack, D. (2012). Do infants have a sense of fairness? Psychological Science, 23(2), 196-204.

Starmans, C., Sheskin, M., & Bloom, P. (2017). Why people prefer unequal societies. Nature Human Behaviour, 1(4), 0082.

Steinbeis, N., & Singer, T. (2013). The effects of social comparison on social emotions and behavior during childhood: The ontogeny of envy and Schadenfreude predicts developmental changes in equity-related decisions. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 115(1), 198-209.

Tabibnia, G., Satpute, A. B., & Lieberman, M. D. (2008). The sunny side of fairness: preference for fairness activates reward circuitry (and disregarding unfairness activates self-control circuitry). Psychological Science, 19(4), 339-347.

Tomasello, M., & Vaish, A. (2013). Origins of human cooperation and morality. Annual review of psychology, 64, 231-255.

Tyler, T. R. (2000). Social justice: Outcome and procedure. International journal of psychology, 35(2), 117-125.

Tyler, T. R., & Blader, S. L. (2000). Cooperation in groups: Procedural justice, social identity, and behavioral engagement. Psychology Press.

van Wolkenten, M., Brosnan, S. F., & de Waal, F. B. (2007). Inequity responses of monkeys modified by effort. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(47), 18854-18859.

Whitt, S., & Wilson, R. K. (2007). The dictator game, fairness and ethnicity in postwar Bosnia. American Journal of Political Science, 51(3), 655-668.

0 Comments