Is the Mal’ta-Buret culture the prototyp for world religion?

In the remote reaches of Siberia, archaeologists uncovered a fascinating window into the deep prehistory of human symbolic thought: the Mal’ta-Buret’ culture. Dating back some 20,000-25,000 years, this Paleolithic society left behind intriguing artifacts that resonate uncannily with mythological motifs from much later periods (Bednarik, 2012). From exquisite Venus figurines to mysterious bird-man statuettes, the Mal’ta-Buret’ culture offers a tantalizing glimpse into the ancient wellsprings of the mythic imagination (Lbova, 2014).

As we compare the Mal’ta-Buret’ material to later mythologies worldwide, striking parallels emerge. The “Adam and Eve” figures of the Judeo-Christian tradition find echoes in creation myths from the Norse to the Cherokee, which also feature primal male-female pairs (Leeming, 2010). The Venus figurines, with their abundant feminine attributes, evoke the “Great Mother” archetype that would recur in goddess cults and sacred art from Eurasia to the Americas (Neumann, 1955).

These confluences raise profound questions: did the Mal’ta-Buret’ culture directly influence later mythic traditions? Or do these common motifs reflect something deep-seated in the human psyche – universal archetypes that arise spontaneously across cultures?

Jungian scholar Erich Neumann argued the latter in his seminal work “The Great Mother” (Neumann, 1955). He saw the recurring figure of the primordial goddess as an expression of the “Great Round” – the archetype of the eternal feminine, the generative and destructive forces of nature. From the corpulent Venuses of Mal’ta to the “Venus of Willendorf” in Europe to voluptuous fertility goddesses worldwide, Neumann perceived a common psychological substratum: the projection of the archetypal Feminine onto sacred iconography (Neumann, 1955).

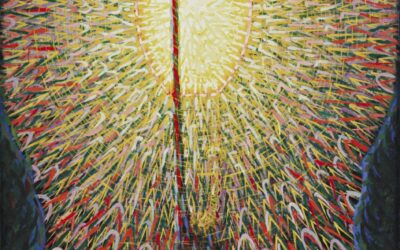

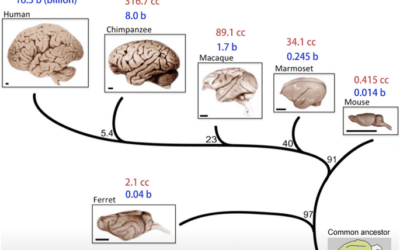

Intriguingly, this flowering of symbolic female representation coincides with a key threshold in cognitive evolution: the development of the precuneus, a region of the brain crucial for imaginative thought and self-representation (Bruner, 2014). As humans developed the capacity for abstract thinking and mental time travel, external representations like figurative art became vital vehicles for meaning-making (Bruner, 2014). The Mal’ta-Buret’ Venuses, with their exaggerated features and lack of facial detail, are less portraits than archetypal embodiments – conceptual projections of the Eternal Feminine onto ivory fetishes (Bednarik, 2012).

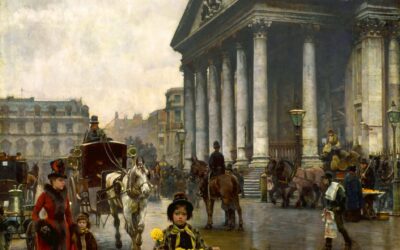

This shift to “external representation” may also underpin another key mythological parallel: the “Garden of Eden” motif, the idea of a lost primal paradise. Many mythologies worldwide, from Sumer to the Aztec, feature a primordial golden age when humanity lived in harmony with nature and the gods (Eliade, 1959). With the advent of self-representation, humans could conceptualize themselves as separate from the world, and hence imagine being expelled from an original unity (Campbell, 1988).

The Mal’ta-Buret’ culture, with its semi-subterranean dwellings marked off from the surrounding landscape, may reflect an early manifestation of this sense of separation between human and natural domains (Kind, 2016). The construction of ritual spaces distinct from the outside world – a practice that would become central to later religious traditions – hints at an emerging sense of alienation from the primordial matrix, the “paradise” before self-consciousness (Eliade, 1959).

This theme of “loss of original unity” was central to Neumann’s conception of human psychological development. He argued that individual ego formation follows the same pattern as mythological narratives of “the Fall”: a painful but necessary separation from the “uroboros”, the primordial unity of child and mother, human and nature (Neumann, 1954). The Mal’ta-Buret’ culture, poised on the cusp of a new mode of symbolic thought, may embody this archetypal transition.

Another intriguing thematic link between Mal’ta-Buret’ and later mythologies is the concept of the primordial pair, exemplified by Adam and Eve. The idea of a primal, often incestuous couple from which humanity descends is widespread – seen in the Norse Ask and Embla, the Mayan Xmucane and Xpiacoc, and the Cherokee “Corn Woman and Lucky Hunter” (Leeming, 2010). Some thinkers have even argued that the Adam and Eve story originated as a Hebrew version of the Indo-European myth of the “divine twins” (Witzel, 2012).

While there’s no evidence that the Mal’ta-Buret’ people directly influenced these later narratives, the presence of male-female pairs among their figurines is suggestive (Lbova, 2014). The fact that one of the most famous Mal’ta artifacts is of a woman and a man standing back to back implies that this culture recognized some mythically-charged link between the two sexes. Whether they had a developed “primal pair” mythology is unclear – but they clearly had the psychic underpinnings for such concepts (Bednarik, 2012).

As we ponder these parallels, it’s crucial to resist reductive notions of direct transmission that ignore cultural complexity. The mythological similiarities between Mal’ta-Buret’ and later societies likely represent not literal influence, but the common archetypes of the collective unconscious finding expression in culturally-specific forms (Campbell, 1988). The Venus figurines, Eden-like dwellings, and primal pairs of Mal’ta are ancestral expressions of psychological patterns that continued to evolve into the richer mythic narratives of Eurasia and beyond.

At the same time, the Mal’ta-Buret’ culture remains crucial for our understanding of prehistoric religious consciousness. It represents an early crystallization of key concepts – goddess worship, ceremonial architecture, mythic iconography – that would shape the human mythic imagination for millennia to come (Kind, 2016). While not a direct “source” for the belief systems of more recent eras, it indicates the deep antiquity of the spiritual impulses that make us human.

As we study these evocative artifacts from the Siberian Ice Age, we’re reminded that mythology is ultimately rooted in the timeless depths of the human psyche. The “eternal archetypes” proposed by Jung and Neumann – the Great Mother, the divine child, the axis mundi – were already finding expression in the art of these vanished Paleolithic societies (Jung, 1991; Neumann, 1955). By contemplating the Mal’ta-Buret’ culture, we catch a glimpse of the primal wellsprings of human symbolic thought – and the enduring power of the mythic imagination.

12 Striking Parallels Between the Mal’ta-Buret’ Culture and World Mythology

The Great Mother Archetype:

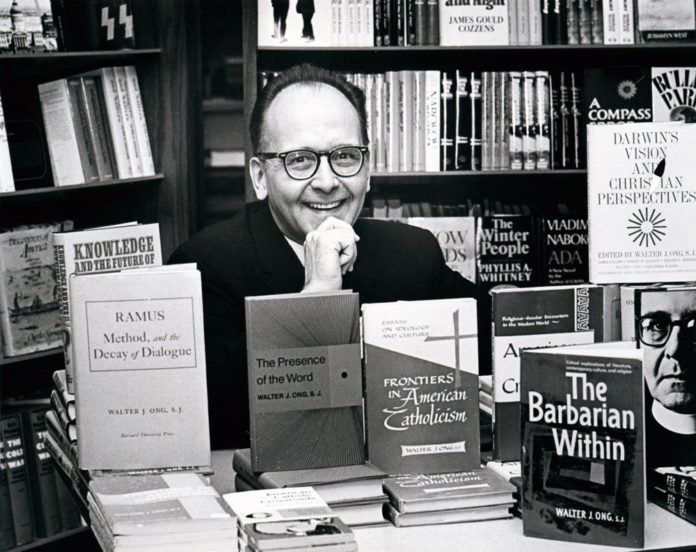

The abundant Venus figurines of Mal’ta-Buret’ echo the “Great Mother” archetype that recurs in goddess worship and sacred art worldwide, from the Venus of Willendorf to the fertility deities of ancient Mesopotamia, Greece, and India (Neumann, 1955).

Shamanic Animal Symbolism:

The bird-man figurines of Mal’ta suggest early shamanic beliefs, paralleling the animal symbolism and therianthropic imagery found in shamanic traditions from Siberia to the Americas (Winkelman, 2002).

Axis Mundi and Sacred Space:

The structured dwellings of Mal’ta-Buret’, with their sense of bounded sacred space, evoke the archetypal concept of the ‘axis mundi’ or cosmic center found in countless mythologies and religious architectures (Eliade, 1959).

The Divine Twins:

The famous “back-to-back” male-female figurine from Mal’ta hints at the concept of primordial pairs or divine twins, a mytheme that recurs from the Norse Ask and Embla to the Mayan Xmucane and Xpiacoc (Witzel, 2012).

The Garden of Eden Motif:

The sense of bounded space and separation from nature suggested by Mal’ta-Buret’ dwellings parallels the cross-cultural mythological motif of a lost primal paradise or “Garden of Eden” (Eliade, 1959).

Paleolithic “Venus” Figurines:

The Mal’ta Venus figurines, with their exaggerated feminine attributes, are part of a wider tradition of Paleolithic “Venus” figurines that stretch across Eurasia, hinting at a shared symbolic underpinning (Dixson & Dixson, 2011).

The Precuneus and Symbolic Thought:

The rise of figurative art and external symbolism in the Upper Paleolithic, as seen at Mal’ta-Buret’, coincides with the development of the precuneus, a part of the brain crucial for higher-order cognition and self-representation (Bruner, 2014).

Jungian Archetypes:

The striking parallels between Mal’ta-Buret’ iconography and later mythic motifs suggest the operation of Jungian archetypes – universal patterns in the collective unconscious that shape human symbolic expression (Jung, 1991).

Neumann’s “Great Round”:

The Mal’ta-Buret’ Venus figurines can be seen as early expressions of what Jungian scholar Erich Neumann called the “Great Round” – the archetypal feminine as a symbol of the cyclical, generative forces of nature (Neumann, 1955).

Mythic Consciousness:

The rich symbolic world of the Mal’ta-Buret’ culture provides a window into what anthropologist Lucien Levy-Bruhl called the “mythic consciousness” of prehistoric societies, a mode of thought that perceived the world as suffused with supernatural meaning (Levi-Bruhl, 1926).

Paleolithic “Proto-Mythology”:

While we can’t know the specific myths of the Mal’ta-Buret’ people, their symbolic artifacts suggest a form of “proto-mythology” – a nascent capacity for metaphorical and symbolic thought that would underpin later mythological systems (Witzel, 2012).

The Origins of Religion:

The Mal’ta-Buret’ culture, with its intimations of shamanism, goddess worship, and mythic symbolism, provides a tantalizing glimpse into the deep prehistory of human religious thought and the enduring power of the mythic imagination (Kind, 2016).

Bibliography:

Bednarik, R. G. (2012). The Origins of Human Modernity. Humanities, 1(1), 1-53.

Bruner, E. (2014). Functional morphology, biomechanics and the retrodiction of early hominin cognition. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 277.

Campbell, J. (1988). The Power of Myth. New York: Doubleday.

Eliade, M. (1959). The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

Jung, C. G. (1991). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious (2nd ed.). Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

Kind, C.-J. (2016). The Smile of the Lion Man. Early Figurative Art in Europe, Western Germany. Expression, 14, 8-20.

Lbova, L. (2014). The Upper Paleolithic of Northeast Asia. In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology (pp. 7571-7577). New York, NY: Springer New York.

Leeming, D. A. (2010). Creation Myths of the World: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO.

Neumann, E. (1954). The Origins and History of Consciousness. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Neumann, E. (1955). The Great Mother: An Analysis of the Archetype. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Witzel, E. J. M. (2012). The Origins of the World’s Mythologies. New York: Oxford University Press.

0 Comments