What Does the Witch Represent in Psychology?

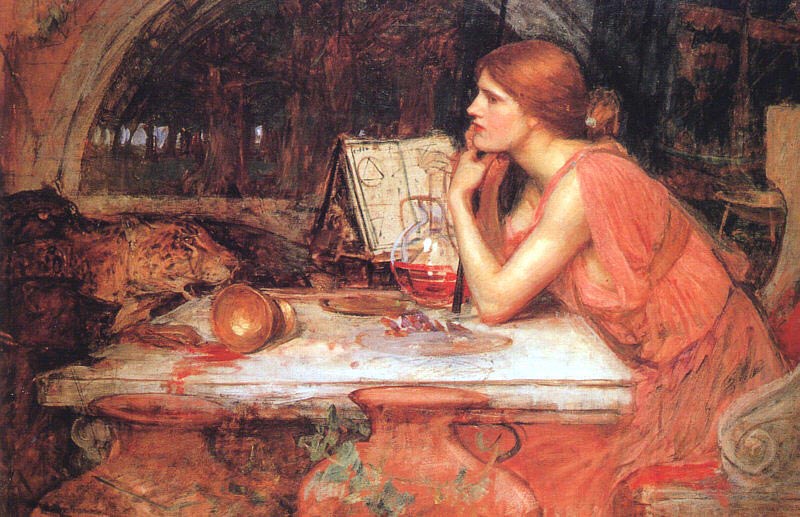

Waterhouse paints Circe’s stream of water as a spiral, something water does not normally do

As the nights grow longer and Halloween draws near, our thoughts turn to the spooky, the mystical, and the uncanny. This is the time of year when we confront the shadows – both literal and psychological. One of the most potent and pervasive archetypal images associated with this season is the witch. Reviled and revered, persecuted and empowered, the witch has haunted the human psyche for centuries.

But who is the witch, really? Is she merely a Halloween caricature – a green-skinned, warty-nosed hag brewing noxious potions? Or does she represent something deeper, a fundamental aspect of the human experience? This paper will argue that the witch is a manifestation of the universal archetype of the divine feminine, the anima, in both her light and shadow aspects. By tracing the witch’s history from ancient nature goddess to medieval devil-worshipper to modern feminist icon, we can shed light on the enduring power of this archetype, and what she might have to teach us about embracing the fullness of our humanity.

The Jungian Perspective: Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious

To understand the archetype of the witch, we must first delve into the realm of Jungian psychology. Carl Jung, the Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, proposed that in addition to our personal unconscious – the repository of our individual memories, impulses, and repressions – there exists a deeper layer of the psyche that is universal and impersonal. He called this the collective unconscious, and argued that it contains archetypes – primordial images and patterns that have existed since the dawn of humanity (Jung, 1968).

These archetypes are not inborn ideas, but rather “typical modes of apprehension” (Jung, 1968, p. 137) – ways of perceiving and responding to the world that have been shaped by our evolutionary history. They manifest in the themes and characters that appear again and again in myths, fairy tales, dreams, and religious iconography across cultures. Some of the most prominent Jungian archetypes include the Shadow (the repressed or denied aspects of the self), the Anima/Animus (the unconscious feminine/masculine qualities in men/women), the Wise Old Man, the Great Mother, the Divine Child, the Trickster, and the Hero.

The witch, I will argue, is a specific manifestation of the anima archetype – the unconscious feminine within the male psyche. According to Jung (1968), the anima takes on different forms as a man develops psychologically. In her most basic, undifferentiated form, she appears as Eve – the purely instinctual feminine. As a man individuates, the anima progresses through the archetypes of Helen (a Romantic and aesthetic ideal), Mary (the spiritual and nurturing mother), and Sophia (transcendent wisdom). But the anima also has a shadow side, associated with the seductive, ensnaring, or enraged aspects of the feminine. The witch embodies this shadow anima – the feared and denied aspects of feminine power.

Yet the archetype of the witch is not solely a product of the male unconscious. Women too have wrestled with this potent and ambivalent symbol of feminine might. The Jungian analyst M. Esther Harding, in her seminal work Woman’s Mysteries Ancient and Modern, argues that the witch represents the “woman’s mysteries” – the “pattern of feminine initiation” that has existed since ancient times (1973, p. xvi). This initiation involves a descent into the underworld of the unconscious, a confrontation with the dark feminine, and an emergence into a new level of awareness and power.

The Universal Witch: Tracing the Archetype Across Cultures

With this Jungian framework in mind, let us now examine how the archetype of the witch has manifested in myths, stories, and traditions across the world. While each culture has its own unique expression of this archetype, certain universal themes emerge.

The Witch as Nature Goddess

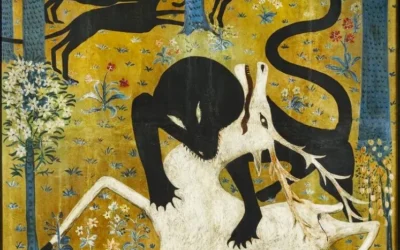

In many ancient traditions, the figure of the witch was synonymous with the nature goddess – the embodiment of the earth’s fertility, power, and mystery. These goddesses ruled over the realms of birth, death, and regeneration, and were often associated with the moon, the sea, and the underworld.

One of the earliest and most iconic examples is the Greek goddess Hecate. Originating in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey), Hecate was initially a Mother Goddess associated with wilderness, childbirth, and the protection of the home (Rigoglioso, 2009). As her cult spread to Greece, she became increasingly linked with the moon, magic, and liminal spaces such as crossroads and thresholds. She was one of the few deities who could move freely between the realms of the living, the dead, and the immortal. In later Greek mythology, she is described as a chthonic (underworld) deity, a patron of witchcraft, and a leader of the restless dead (Ronan, 1992).

Hecate’s triple-formed statue – depicting her as maiden, mother, and crone – hints at her role as a goddess of the life cycle. This triune nature is echoed in other Indo-European witch-goddesses such as the Celtic Morrigan (the “phantom queen” who takes the form of maiden, mother, and hag) and the Germanic Norns (the three wise women who spin, measure, and cut the threads of fate). These figures represent the full spectrum of feminine power – alluring, nurturing, and terrifying.

Another key aspect of the witch-as-nature-goddess is her association with herbalism, midwifery, and healing. The ancient Greek Circe, sometimes depicted as a witch and other times as a goddess, was renowned for her vast knowledge of drugs and herbs (Homer, trans. 1996). In The Odyssey, she transforms Odysseus’s men into pigs using a magic potion, but later uses her herbal skill to help the hero on his journey homeward.

Similarly, the Norse Völva (seeresses) and the Celtic druidesses were highly respected for their mastery of herbal lore and natural magic (Davidson, 1988). They acted as midwives, healers, and oracles, using their “witchcraft” for the good of the community.

In these ancient traditions, then, the witch was not a figure of pure evil, but rather an embodiment of the mysteries of nature, the numinous feminine, and the cycle of life and death. She dwelt in the liminal places – the wild forests, the trackless fens, the misty borderlands between worlds – guarding the secrets of birth, sex, death, and rebirth. To encounter her was to confront the untamed power of the anima mundi, the soul of the world.

The Shadow Witch: Demonization and Persecution

But as patriarchal cultures rose to dominance, the archetype of the witch underwent a profound transformation. No longer honored as a nature goddess, she was increasingly demonized as a servant of evil, a threat to the righteous order. The witch became the shadow of the “good mother” – the seductive temptress, the child-killing hag, the consort of the devil.

This shift can be traced in Judeo-Christian mythology, which reimagines the pagan goddesses as demons and fallen angels. The biblical figure of Lilith – Adam’s rebellious first wife turned baby-snatching succubus – has roots in the Sumerian demon Lamashtu and the Jewish folk-demon Lili (Patai, 1990). Likewise, the Canaanite mother goddess Asherah was vilified in the Bible as a false idol, her sacred groves cut down by the zealous reformer King Josiah (Olyan, 1988).

This pattern of demonization reached its terrible apex in the European witch-hunts of the 15th-17th centuries. Guided by texts such as the infamous Malleus Maleficarum (1487), inquisitors and magistrates tortured and executed tens of thousands of alleged witches, 80% of whom were women (Ehrenreich & English, 1973). The accused were said to worship the devil, fly on broomsticks, engage in lewd sexual rites, cause crop failures and stillbirths, and sacrifice unbaptized infants (Russell & Alexander, 2007).

What drove this frenzy of persecution? Feminist historians argue that the witch-hunts were, in part, an attempt to suppress the vestiges of pagan goddess-worship and eliminate women’s traditional medical and reproductive knowledge (Ehrenreich & English, 1973). Midwives, herbalists, and folk healers – those who preserved the ancient “women’s mysteries” – were prime targets. In a time of profound social upheaval, the witch represented the chaotic, ungovernable aspects of nature and the feminine that needed to be brought to heel.

Yet even in this diabolical guise, the witch remained a potent and ambivalent figure. She was both feared and desired, reviled and secretly admired. After all, her power was undeniable, even as it was condemned. In fairy tales and folk legends, the wicked witch is often the one who holds the key to the hero’s quest – think of the Baba Yaga in Russian tales, who can be a source of great wisdom or a child-eating ogress depending on how she is approached (G., 2020).

Behind the lurid accusations leveled against these “witches,” one can discern a hidden respect for feminine knowledge and power. The witch may have been pushed to the margins, but she could never be wholly eradicated. She haunts the edges of patriarchal civilization, a reminder of the repressed feminine, the untamed anima.

Reclaiming the Witch: Modern Jungian and Feminist Perspectives

In the 20th and 21st centuries, Jungian analysts and feminist thinkers have sought to rehabilitate the archetype of the witch, recognizing her as a potential source of feminine empowerment. Rather than rejecting the “dark” aspects of the anima, they argue, we must confront and integrate them.

The Jungian analyst Clarissa Pinkola Estés, in her bestselling book Women Who Run with the Wolves, identifies the witch as one of the key expressions of the “Wild Woman” archetype – the instinctual, untamed feminine that exists in all women. Drawing on myths, fairy tales, and dream analysis, Estés (1992) shows how patriarchal culture suppresses this wild nature, viewing it as dangerous and devilish. Women are encouraged to be docile, compliant, “nice” – while their rage, their hunger, their sexual power, their creativity, is consigned to the shadow.

To reclaim the witch, then, is to embrace the fullness of the feminine self – light and dark, nurturing and destructive, spiritual and sexual. It is to celebrate the “woman’s mysteries” that patriarchal culture has long demonized: the magic of menstruation, the power of female sexuality, the wisdom of the female body. The witch, in this sense, represents the elemental feminine – the anima not as a male projection, but as a woman’s deepest self.

This empowered witch can be glimpsed in modern pagan and Wiccan traditions, which revere the witch as a priestess of the Goddess, a healer and wise woman (Adler, 2006). She is present in feminist activism, where “witch” has been reclaimed as a title of honor – think of W.I.T.C.H. (Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell), a radical feminist group that hexed Wall Street and the patriarchy in the 1960s (Brownmiller, 1999). And she inspires contemporary female artists, from Niki de Saint Phalle’s colorful “Nana” sculptures to Beyoncé’s fierce, transgressive persona in the visual album Lemonade.

Yet even as the witch is reclaimed as a feminist symbol, her shadow aspects cannot be ignored. The Jungian analyst Barbara Koltuv (1986), in her book The Book of Lilith, warns that an overidentification with the “dark feminine” can lead to grandiosity, destructiveness, and a rejection of the “light” aspects of the self. A true integration of the anima, she argues, requires a confrontation with both the light and dark sides of the archetype.

Moreover, as the Jungian analyst Naomi Lowinsky (2009) points out, the reclamation of the witch can sometimes perpetuate the patriarchal split between the “good” and “bad” woman. The feminist witch is often seen as a “strong, independent woman” who rejects traditional feminine roles – but this can implicitly devalue the softer, more receptive qualities associated with the “good mother.” A true reclaiming of the feminine, Lowinsky suggests, would integrate all aspects of the archetype – maiden, mother, and crone; witch and saint.

Embodying the Witch: A Path of Feminine Empowerment

So what does it mean to embody the archetype of the witch in our own lives? How can we tap into her power in a way that is healing, transformative, and ethical?

At its core, embodying the witch is about reclaiming the sacred feminine in all its forms. It means honoring the wisdom of the body, the emotions, and the intuition – those aspects of the self that patriarchal culture has often denigrated or suppressed. The witch knows that the body is not a mere vessel for the mind, but a powerful source of insight, pleasure, and magic. She celebrates the cycles of the menstrual cycle, the phases of the moon, the seasons of the earth, seeing in them a reflection of the deep rhythms of the cosmos.

Embodying the witch also means embracing the full spectrum of human emotions, from joy and ecstasy to grief and rage. The witch understands that emotions are not something to be repressed or controlled, but a potent form of energy that can be harnessed for transformation. She knows how to sit with her pain, to alchemize her anger into action, to channel her desire into creation. In a culture that often demands emotional suppression, especially from women, the witch’s radical self-acceptance can be a revolutionary act.

The path of the witch is also one of deep communion with the natural world. The witch sees herself not as separate from nature, but as an integral part of the web of life. She studies the lore of plants and animals, the movements of the stars and planets, the subtle energies of the elements. She knows how to call upon the powers of the earth, the sea, the sky, to heal and to transform. For the witch, magic is not a supernatural power, but the art of working in harmony with the forces of nature to manifest change.

This deep attunement to nature goes hand-in-hand with a commitment to ecological sustainability and social justice. The witch understands that the exploitation of the earth and the oppression of marginalized peoples are two sides of the same coin – a worldview that sees the “other” as something to be dominated and controlled. By contrast, the witch seeks to cultivate right relationship with all beings, human and more-than-human. She uses her magic to heal the earth, to fight for the rights of the oppressed, to create a world where all can thrive.

Embodying the witch also means developing a deep trust in one’s own inner knowing. The witch is the ultimate nonconformist, the one who dares to think and act outside the bounds of social convention. She trusts her intuition, her dreams, her visions, even when they fly in the face of consensus reality. This self-trust is not a form of narcissism or isolationism, but a radical reclaiming of one’s own authority and agency. In a world that constantly seeks to undermine women’s sense of self, the witch’s unshakable inner compass is a powerful tool of resistance.

Part of this self-trust involves a willingness to confront one’s own shadow – those aspects of the self that we fear, deny, or repress. The witch knows that the path to wholeness leads through the darkness, not around it. She is willing to face her own wounds, her own shortcomings, her own capacity for destruction, knowing that only by integrating the shadow can she truly wield her power with wisdom and compassion. This is the true meaning of the “witch’s initiation” – a descent into the underworld of the psyche, a confrontation with death and rebirth.

Ultimately, embodying the witch is about reclaiming the sacred in a world that has largely forgotten it. The witch understands that the divine is not something separate from the world, but immanent in every atom, every cell, every living being. She experiences the numinous in the everyday – in the play of light on water, the taste of wild berries, the touch of a lover’s skin. For the witch, magic is not a rare and esoteric art, but the very fabric of reality, available to all who have eyes to see and ears to hear.

Of course, walking the path of the witch is not without its challenges and dangers. In a world still haunted by the specter of the witch-hunts, to claim the mantle of the witch is to risk being misunderstood, ridiculed, even persecuted. It means daring to stand out, to challenge the status quo, to speak truth to power. It means being willing to be a thorn in the side of the comfortable, a voice for the voiceless, a midwife to the birth pangs of a new world.

But for those who feel called to this path, the rewards are beyond measure. To embody the witch is to step into a lineage of powerful women stretching back to the dawn of time. It is to reclaim one’s birthright as a co-creator of reality, a shaper of destiny, a healer of worlds. It is to know the rapture of dancing under the full moon, the satisfaction of brewing a perfect healing potion, the joy of sharing one’s gifts with a grateful community.

More than anything, embodying the witch is about living a life of authentic self-expression, in deep alignment with one’s own soul and the soul of the world. It is about daring to be fully, unapologetically oneself, in service to a vision of a world where all beings can flourish. In a time of great uncertainty and upheaval, the way of the witch offers a path of profound resilience, creativity, and hope. May we all find the courage to walk it, and in so doing, weave a new world into being.

Timeline of the Development of The Witch Archetype Across Cultures

The Witch in Scandinavia

- Ancient North Eurasian shamanic practices (c. 8000 BCE – 3000 BCE)

- Shamanic rituals involving trance, spirit communication, and healing magic

- Veneration of nature spirits and ancestor spirits

- Use of animal symbolism, such as the bird and the bear, in shamanic costumes and iconography

- Possible migration of North Eurasian shamanic practices to Scandinavia via the Sámi people

- Norse paganism and the worship of goddesses like Freyja, Frigg, and the Norns (c. 500 BCE – 1000 CE)

- Freyja as the goddess of magic, sexuality, and war, patron of the Völva (seeresses)

- Associated with the practice of seiðr, a form of magic involving shamanic trance and divination

- Myths of Freyja riding through the night sky with the spirits of the dead, associated with the Wild Hunt

- Frigg as the goddess of marriage, motherhood, and domestic arts, associated with spinning and weaving fate

- Her role as a seeress and practitioner of magic, as evidenced in the Eddic poem “Lokasenna”

- Her association with the distaff, a spinning tool later linked to witchcraft accusations

- The Norns as the three goddesses who spin, measure, and cut the threads of destiny

- Their depiction at the foot of the world tree Yggdrasil, determining the fates of gods and mortals

- Their association with wells and water, sites of feminine power and prophecy

- Freyja as the goddess of magic, sexuality, and war, patron of the Völva (seeresses)

- Viking Age and the spread of Norse beliefs throughout Europe (c. 800 – 1100 CE)

- Viking raids and settlements in Britain, Ireland, France, and beyond

- Transmission of Norse mythological themes and motifs into Celtic and Anglo-Saxon cultures

- Possible influence of the Völva on later Celtic and Germanic ideas of witchcraft

- Development of the Völva as a respected class of magical practitioners, associated with divination, shamanism, and the practice of seiðr

- The account of the Völva Thorbjorg in the Saga of Erik the Red, who performs a shamanic ritual to predict the future

- Archaeological evidence of Völva graves containing ritual staffs, herbs, and other magical implements

- Ambivalent attitude towards male practitioners of seiðr, seen as unmanly and potentially dishonorable

- The god Odin as the ultimate master of seiðr, but also mocked for his “womanly” ways

- Viking raids and settlements in Britain, Ireland, France, and beyond

- Christianization of Scandinavia and the suppression of pagan beliefs (c. 1000 – 1500 CE)

- Gradual conversion of Scandinavian kingdoms to Christianity, beginning with Denmark in the 10th century

- The efforts of missionaries like Ansgar, the “Apostle of the North”

- The influence of Christian kings like Olaf Tryggvason and Olaf Haraldsson, who forcibly converted their subjects

- Suppression and demonization of pagan deities and practices, including the outlawing of seiðr

- The depiction of Freyja and other Norse goddesses as demons or “witches” in Christian sources

- The association of Völva with evil sorcery and devil-worship

- Syncretic fusion of Christian and pagan elements in folk religion, such as the association of St. Brigid with the goddess Frigg

- Continued belief in magic, divination, and herbalism among the peasantry

- The persistence of pagan festivals and customs, such as the Yule celebration of midwinter

- Gradual conversion of Scandinavian kingdoms to Christianity, beginning with Denmark in the 10th century

- Early modern witch trials in Scandinavia, such as the Torsåker witch trials in Sweden (1674 – 1675)

- Influence of continental European witch-hunt manuals and demonological theories, such as the Malleus Maleficarum

- The role of Lutheran clergy in promoting belief in diabolical witchcraft

- The use of torture to extract confessions and accusations

- Accusations of diabolical witchcraft, including pacts with the devil, attendance at sabbats, and maleficent magic

- The Torsåker trials’ focus on alleged child-witches and their recruitment by older female witches

- The “Witch-Hammer” of Ålholm Castle, a 17th-century torture device used in Danish witch trials

- Particular targeting of Sámi noaidi (shamans) and other practitioners of traditional magic

- The trial and execution of the Sámi shaman Lars Nilsson in Sweden (1693)

- The demonization of Sámi drum magic and spirit journeys as “witchcraft”

- Influence of continental European witch-hunt manuals and demonological theories, such as the Malleus Maleficarum

- Romantic Nationalism and the revival of interest in Norse mythology (1800s)

- Rediscovery and reinterpretation of Old Norse literature, including the Poetic Edda and the Icelandic sagas

- The publication of the Prose Edda by the Icelandic scholar Snorri Sturluson (1220)

- The influence of the Eddas on Romantic poets and artists, such as Adam Oehlenschläger and N.F.S. Grundtvig

- Incorporation of Norse mythological themes into Romantic art, music, and literature

- Richard Wagner’s operatic cycle “Der Ring des Nibelungen” (1876), inspired by Norse and Germanic myths

- J.R.R. Tolkien’s “The Lord of the Rings” (1954), which drew heavily on Norse concepts of magic, fate, and heroism

- Emergence of the “Gothic” aesthetic, which drew on medieval and pagan imagery

- The Victorian fascination with the “Gothic witch,” a seductive and dangerous femme fatale

- The influence of this trope on later depictions of Viking and Norse witch-figures

- Rediscovery and reinterpretation of Old Norse literature, including the Poetic Edda and the Icelandic sagas

- Modern Scandinavian folklore studies and the collection of tales featuring witch figures (late 1800s – early 1900s)

- Collection and publication of folktales, legends, and ballads by scholars like Peter Christen Asbjørnsen, Jørgen Moe, and Evald Tang Kristensen

- Asbjørnsen and Moe’s “Norwegian Folktales” (1841-1844), which included many tales of witches, trolls, and other supernatural beings

- Kristensen’s “Danish Fairy Tales” (1881), which featured stories of wise women, healing magic, and shapeshifting witches

- Documentation of living folk beliefs and practices related to magic, healing, and witchcraft

- The work of Norwegian folklorist Sigurd Solheim on the figure of the “gandferd,” a witch who could send out her spirit in the form of an animal

- The research of Danish folklorist Ferdinand Ohrt on the persistence of pagan magical practices in rural communities

- Influence of folklore studies on the development of Scandinavian literature, art, and national identity

- The use of witch and troll figures in the plays of Henrik Ibsen, such as “Peer Gynt” (1876)

- The paintings of Norwegian artist Theodor Kittelsen, which depicted the witch as a grotesque and menacing figure

- Collection and publication of folktales, legends, and ballads by scholars like Peter Christen Asbjørnsen, Jørgen Moe, and Evald Tang Kristensen

- Contemporary Scandinavian Neopaganism and the reclamation of the witch as a feminist symbol (1960s – present)

- Emergence of Asatru (Norse Neopaganism) and other Pagan revivals in Scandinavia

- The founding of the Icelandic Ásatrúarfélagið (1972), the first officially recognized Asatru organization

- The growth of Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish Asatru groups in the 1990s and 2000s

- Feminist reinterpretations of Norse goddesses and the Völva as symbols of female power and wisdom

- The work of Swedish archaeologist and feminist Britt-Mari Näsström on the cult of Freyja

- The reclamation of the Völva as a shamanic healer and visionary in contemporary Goddess spirituality

- Incorporation of Scandinavian witch imagery into popular culture, such as film and television

- The Danish TV series “The Shamer’s Daughter” (2015), based on a series of fantasy novels about a young girl with magical powers

- The Norwegian film “Thelma” (2017), a supernatural thriller about a young woman with telekinetic abilities

- The continued fascination with the figure of the “Scandinavian witch” in horror and fantasy media worldwide

- Emergence of Asatru (Norse Neopaganism) and other Pagan revivals in Scandinavia

Timeline of the Development of the Witch in Germany

- Ancient North Eurasian shamanic practices (c. 8000 BCE – 3000 BCE)

- Shamanic rituals involving trance, spirit communication, and healing magic

- Veneration of nature spirits and ancestor spirits

- Use of animal symbolism, such as the bird and the bear, in shamanic costumes and iconography

- Possible migration of North Eurasian shamanic practices to Germany via Indo-European tribes

- Germanic paganism and the worship of goddesses like Holda, Berchta, and the Valkyries (c. 500 BCE – 1000 CE)

- Holda (or Frau Holle) as the goddess of the wild hunt, associated with winter, spinning, and the underworld

- Her dual nature as a benevolent mother figure and a fearsome hag

- Her association with the “Wild Hunt,” a ghostly procession of the dead

- The legends of Holda rewarding industrious spinners and punishing lazy ones

- Berchta (or Perchta) as the goddess of agriculture, fertility, and the dead

- Her role as a guardian of the spinning room and a patron of female domestic arts

- Her terrifying aspect as a child-stealing hag with a iron nose

- The Perchten processions of masked figures during the Twelve Days of Christmas, possibly remnants of pagan winter rites

- The Valkyries as the female warrior spirits who escort the fallen to Valhalla

- Their depiction as fierce, swan-cloaked maidens who ride through the air

- Their association with battle magic and the weaving of fate

- The possible continuity between the Germanic Valkyries and earlier Indo-European goddesses like the Greek Furies

- Holda (or Frau Holle) as the goddess of the wild hunt, associated with winter, spinning, and the underworld

- Christianization of Germany and the suppression of pagan beliefs (c. 700 – 1500 CE)

- Missionary efforts of Anglo-Saxon and Irish monks, such as St. Boniface

- Boniface’s felling of the sacred Oak of Thor at Geismar (723 CE)

- The establishment of Christian monasteries and bishoprics throughout Germany

- Gradual conversion of Germanic kingdoms to Christianity, culminating in the baptism of Widukind in 785 CE

- The Saxon Wars and Charlemagne’s forcible conversion of the pagan Saxons

- The destruction of pagan temples and sacred sites

- Syncretic fusion of Christian and pagan elements in folk religion

- The association of St. Walpurga (an English missionary) with the pagan festival of Walpurgisnacht

- The persistence of pagan deities and nature spirits as fairies, dwarfs, and kobolds in German folklore

- The continued practice of magic, divination, and herbal healing among the peasantry

- Missionary efforts of Anglo-Saxon and Irish monks, such as St. Boniface

- Medieval legends and folk tales featuring witch figures, such as the “Witch of Freiburg” (recorded in the 1400s)

- Legends of women who sold their souls to the devil in exchange for magical powers

- The story of Theophilus, a cleric who makes a pact with the devil but is saved by the Virgin Mary

- The legend of the “Witch of Berkeley,” an English tale of a dying witch who summons the devil to take her soul

- Tales of shape-shifting witches who steal children, blight crops, and cause illness

- The “Witch of Freiburg,” a woman accused of killing children and causing miscarriages through her magic

- The “Werewolf of Bedburg,” a 16th-century case of a man accused of shapeshifting and cannibalism

- Association of witches with heresy, moral corruption, and sexual deviance

- The depiction of witches as participants in Satanic orgies and blasphemous rites

- The accusation of witches as “baby-eaters” and consumers of human flesh

- The linking of witchcraft with the heretical movements of the Cathars and Waldensians

- Legends of women who sold their souls to the devil in exchange for magical powers

- Early modern witch trials in Germany, such as the Trier witch trials (1581 – 1593) and the Würzburg witch trials (1626 – 1631)

- Influence of the Malleus Maleficarum and other demonological texts

- Heinrich Kramer’s Malleus Maleficarum (1487), a infamous treatise on the detection and punishment of witches

- The work of German demonologists like Johannes Nider and Johannes Geiler von Kaysersberg

- Accusations of diabolical witchcraft, including pacts with the devil, attendance at sabbats, and maleficent magic

- The Trier witch trials, which resulted in the execution of around 1,000 alleged witches

- The Würzburg witch trials, a series of mass trials that claimed the lives of over 200 people

- High percentage of women, especially widows and midwives, among the accused and executed

- The targeting of marginalized and independent women, such as the elderly, the poor, and the unmarried

- The association of midwifery and folk healing with witchcraft and devil-worship

- The use of torture to extract confessions, often leading to further accusations and a “chain reaction” of trials

- Influence of the Malleus Maleficarum and other demonological texts

- Grimms’ Fairy Tales and the popularization of witch figures in stories like “Hansel and Gretel” and “Snow White” (published 1812 – 1857)

- Collection and adaptation of German folktales by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm

- The Grimms’ methodology of collecting tales directly from oral sources, mostly women

- The editing and “sanitizing” of the tales for a middle-class family audience

- The influence of the Grimms’ tales on the development of the modern fairy tale genre

- Depiction of witches as cannibalistic, child-stealing old women living in the deep forest

- The witch in “Hansel and Gretel” who lures children with her gingerbread house and tries to eat them

- The evil queen in “Snow White” who practices magic and tries to kill her stepdaughter out of jealousy

- The portrayal of witches as the antithesis of the good, nurturing mother figure

- Influence of the Grimms’ tales on the development of children’s literature and the popular image of the fairy tale witch

- The widespread adaptation of Grimms’ tales in books, plays, films, and other media

- The use of the witch as a stock villain in Disney animated films and other children’s entertainment

- The continued association of witches with the dark, wild forest and the threat to innocent children

- Collection and adaptation of German folktales by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm

- Nazi era and the appropriation of Germanic pagan symbolism (1933 – 1945)

- Nazi ideology’s selective use of Germanic pagan imagery and mythology to promote ideas of racial purity and superiority

- The co-optation of runes, swastikas, and other pagan symbols by the Nazi Party

- The portrayal of Hitler as a messianic figure and the Third Reich as a “holy” empire

- The glorification of Germanic warriors and the cult of heroic death

- Heinrich Himmler’s interest in folklore, occultism, and the history of witchcraft

- Himmler’s sponsorship of the “Hexen-Sonderauftrag” (Special Witch Assignment), a pseudoscientific investigation into the history of witch trials

- The SS’s use of Wewelsburg Castle as a center for occult rituals and pagan ceremonies

- The appropriation of the Valkyrie and other Germanic female figures as symbols of Aryan womanhood

- Persecution of Jehovah’s Witnesses, Freemasons, and other groups accused of “witchcraft” and conspiracy

- The labeling of minority religions and esoteric groups as “sects” and enemies of the state

- The imprisonment and execution of Jehovah’s Witnesses and other religious dissidents in concentration camps

- The association of Jews with witchcraft, devil-worship, and ritual murder in Nazi propaganda

- Post-WWII folklore studies and the reinterpretation of witch figures in a cultural-historical context (continued)

- Scholarly examination of the social, economic, and psychological factors behind the early modern witch-hunts

- The work of British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper on the European witch-craze as a product of religious and political tensions

- The research of German scholar Gerd Schwerhoff on the dynamics of accusation and confession in German witch trials

- Feminist analyses of the witch as a symbol of patriarchal oppression and female resistance

- The work of American historian Barbara Ehrenreich and journalist Deirdre English on the witch-hunts as a campaign against women healers and midwives

- The writings of German feminist scholar Silvia Bovenschen on the witch as a symbol of female nonconformity and rebellion

- Increased attention to the role of folk magic, herbal healing, and midwifery in the lives of historical “witches”

- The research of German historian Eva Labouvie on the practices and persecutions of cunning folk and wise women

- The work of Austrian scholar Wolfgang Behringer on the continuity between pre-Christian shamanism and early modern witchcraft beliefs

- Scholarly examination of the social, economic, and psychological factors behind the early modern witch-hunts

- Modern German Neopaganism and Wicca, including feminist reclamations of the witch archetype (1970s – present)

- Emergence of German Neopagan groups, such as the Eldaring and the Verein für germanisches Heidentum

- The revival of Norse and Germanic pagan traditions, often with a focus on environmental sustainability and cultural preservation

- The creation of new rituals and practices based on archaeological and folkloric sources

- Popularity of Wicca and eclectic Neopagan practices, especially among younger generations

- The introduction of Wicca to Germany in the 1970s by American and British practitioners

- The growth of Wiccan covens and solitary practitioners, influenced by the writings of Gerald Gardner and Starhawk

- Feminist Goddess spirituality and the reclamation of the witch as a symbol of female empowerment and ecological awareness

- The work of German feminist theologian Heide Göttner-Abendroth on matriarchal religions and the “sacred feminine”

- The popularity of feminist Wiccan traditions like Dianic Wicca, which emphasize the worship of the Goddess and the empowerment of women

- Emergence of German Neopagan groups, such as the Eldaring and the Verein für germanisches Heidentum

- Nazi ideology’s selective use of Germanic pagan imagery and mythology to promote ideas of racial purity and superiority

The use of the witch as a symbol of resistance against patriarchy, capitalism, and environmental destruction in feminist and leftist activism

Timeline of the Development of the Archetype in the United States

- Pre-colonial Native American shamanic practices and beliefs (c. 10,000 BCE – 1600 CE)

- Diverse traditions of shamanism, spirit communication, and healing magic among indigenous North American cultures

- The role of the shaman or medicine person as a spiritual leader, healer, and interpreter of dreams and visions

- The use of drumming, chanting, and dancing to induce altered states of consciousness and communicate with the spirit world

- Use of plant medicines, sweat lodges, and other techniques to induce altered states of consciousness

- The ritual use of tobacco, peyote, ayahuasca, and other sacred plants to facilitate spiritual experiences and healing

- The construction of sweat lodges and other sacred spaces for purification, prayer, and communion with the spirits

- Importance of animal spirit guides and the concept of “power animals”

- The belief in animal spirits as protectors, teachers, and sources of strength and wisdom

- The use of animal skins, feathers, and other totems in shamanic rituals and costumes

- Belief in witchcraft, sorcery, and malevolent magic among some Native American tribes

- The figure of the “skinwalker” or shapeshifting witch in Navajo and other Southwestern tribal traditions

- The practice of “love magic” and cursing among some Eastern Woodlands and Plains tribes

- The impact of European colonization and Christian missionary activity on traditional Native American beliefs and practices

- Diverse traditions of shamanism, spirit communication, and healing magic among indigenous North American cultures

- Colonial era and the importation of European witch beliefs (1600s – 1700s)

- Puritan theology and the belief in witchcraft as a threat to Christian society

- The writings of Puritan ministers like Cotton Mather and Increase Mather, who argued for the reality of witches and their danger to christians

- Puritan theology and the belief in witchcraft as a threat to Christian society

- Colonial era and the importation of European witch beliefs (1600s – 1700s) (continued)

- Puritan theology and the belief in witchcraft as a threat to Christian society

- The writings of Puritan ministers like Cotton Mather and Increase Mather, who argued for the reality of witchcraft and the need to prosecute witches

- The influence of English and European witch-hunt manuals and demonological texts on colonial religious and legal attitudes

- Accusations of witchcraft among Native American and African populations

- The association of Native American spiritual practices with devil-worship and sorcery by European colonizers

- The fear of African magic and “voodoo” among white slave owners and the use of anti-witchcraft laws to control enslaved populations

- Witch trials in colonial America, such as the Hartford witch trials (1662-1663) and the Stamford witch trials (1692)

- The accusations of witchcraft against unpopular or marginalized members of the community, such as elderly women and social outcasts

- The use of spectral evidence, torture, and other questionable methods to extract confessions and convict suspects

- The legal and religious controversies surrounding the trials and the eventual decline of witch-hunting in the colonies

- Puritan theology and the belief in witchcraft as a threat to Christian society

- Salem Witch Trials in colonial Massachusetts (1692 – 1693)

- Accusations of witchcraft against a group of young girls in Salem Village

- The initial accusations by Abigail Williams and Betty Parris against the slave Tituba and two other marginalized women

- The spread of accusations throughout the community and the involvement of prominent religious and political figures

- The role of social, economic, and religious tensions in fueling the trials

- The conflicts between the wealthy merchant class and the rural farming population in Salem and the surrounding towns

- The power struggles between rival Puritan factions and the influence of radical Puritan ministers like Samuel Parris

- The psychological and social pressures faced by the accused and the accusers, including the use of leading questions and peer pressure

- The legal and religious procedures of the trials and the eventual backlash against the proceedings

- The reliance on spectral evidence and the “touch test” to identify witches

- The role of judges like John Hathorne and Jonathan Corwin in conducting the trials and issuing death sentences

- The critique of the trials by ministers like Increase Mather and the gradual decline of public support for the prosecutions

- The aftermath and legacy of the Salem Witch Trials in American history and culture

- The formal apologies issued by the Massachusetts government to the families of the accused in the 18th and 20th centuries

- The use of the Salem trials as a metaphor for the dangers of mass hysteria, intolerance, and scapegoating in American literature and popular culture

- The impact of the trials on the development of American legal and religious attitudes towards witchcraft and the supernatural

- Accusations of witchcraft against a group of young girls in Salem Village

- Antebellum period and the emergence of Spiritualism and mediumship (mid-1800s)

- The rise of Spiritualism as a religious and social movement in the United States and Europe

- The belief in the ability to communicate with the dead through seances, automatic writing, and other mediumistic practices

- The popularity of Spiritualist circles and the emergence of celebrity mediums like the Fox sisters and Daniel Dunglas Home

- The role of women in the Spiritualist movement and the challenge to traditional gender roles

- The prominence of female mediums and the association of mediumship with feminine sensitivity and intuition

- The use of Spiritualism as a platform for women’s rights and social reform, as exemplified by figures like Victoria Woodhull and Cora L. V. Scott

- The overlap between Spiritualism, mesmerism, and other occult and pseudo-scientific practices

- The influence of Franz Anton Mesmer’s theories of animal magnetism on the development of Spiritualist healing practices

- The use of spirit photography, ectoplasm, and other alleged paranormal phenomena to support the claims of mediums and Spiritualists

- The backlash against Spiritualism and the exposure of fraudulent mediums

- The debunking of Spiritualist claims by stage magicians like Harry Houdini and scientific investigators

- The decline of the Spiritualist movement in the early 20th century and its influence on later New Age and paranormal beliefs

- The rise of Spiritualism as a religious and social movement in the United States and Europe

- Late 19th-century occult revival and the influence of European esotericism (1880s – 1900s)

- The import of European occult and magical traditions to the United States

- The influence of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and other British occult societies on American esotericism

- The translation and publication of key texts of Western esotericism, such as Eliphas Levi’s “Transcendental Magic” and Helena Blavatsky’s “Isis Unveiled”

- The emergence of Theosophy and other esoteric movements in the United States

- The founding of the Theosophical Society by Helena Blavatsky and Henry Steel Olcott in 1875

- The blending of Eastern and Western mystical traditions in Theosophical teachings and the influence on later New Age spirituality

- The popularization of astrology, tarot, and other forms of divination and magic

- The publication of popular books on astrology and other occult subjects, such as William Lilly’s “Christian Astrology” and A.E. Waite’s “Pictorial Key to the Tarot”

- The use of astrology and other forms of divination for personal guidance and spiritual growth, as well as for entertainment and fortune-telling

- The intersection of occultism, feminism, and progressive social movements

- The involvement of women in Theosophy, Spiritualism, and other esoteric groups as leaders and practitioners

- The use of occult and magical practices as tools for personal empowerment and social change, as exemplified by figures like Anna Kingsford and Dion Fortune

- The import of European occult and magical traditions to the United States

- Hollywood’s Golden Age and the popularization of the witch in films like “The Wizard of Oz” (1939) and “I Married a Witch” (1942)

- The depiction of the witch as a comedic and sometimes sympathetic figure in Hollywood films

- The character of Glinda the Good Witch in “The Wizard of Oz” and her contrast with the Wicked Witch of the West

- The portrayal of the witch as a mischievous and seductive woman in films like “I Married a Witch” and “Bell, Book and Candle” (1958)

- The use of special effects and visual spectacle to depict witchcraft and magic on screen

- The iconic scenes of the Wicked Witch of the West melting and the flying monkeys in “The Wizard of Oz”

- The use of animation and trick photography to depict spells and transformations in films like “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” (1937) and “Fantasia” (1940)

- The influence of Hollywood’s portrayal of witches on popular culture and the public imagination

- The enduring popularity and cultural impact of films like “The Wizard of Oz” and their iconography

- The role of Hollywood in shaping public perceptions of witchcraft and the supernatural, both positively and negatively

- The subversive and feminist undertones of some Hollywood witch films

- The portrayal of witches as independent and unconventional women who challenge patriarchal norms and expectations

- The use of witchcraft as a metaphor for female power and sexuality in films like “I Married a Witch” and “Bell, Book and Candle”

- The depiction of the witch as a comedic and sometimes sympathetic figure in Hollywood films

- Counterculture of the 1960s and the influence of second-wave feminism on Neo-Paganism and Wicca

- The emergence of Neo-Paganism and Wicca in the United States as part of the countercultural movement

- The influence of British Wiccan traditions, such as Gardnerian and Alexandrian Wicca, on American practitioners

- The development of eclectic and feminist forms of Wicca, such as Dianic Wicca and the Reclaiming tradition

- The intersection of Neo-Paganism, environmentalism, and the “back-to-the-land” movement

- The emphasis on nature-based spirituality and the celebration of the cycles of the seasons in Neo-Pagan rituals and festivals

- The influence of the “Gaia hypothesis” and other ecological theories on Neo-Pagan conceptions of the earth as a living organism

- The influence of second-wave feminism on the development of goddess-centered spirituality

- The reclamation of the witch as a symbol of female power and rebellion against patriarchy

- The creation of women-only covens and the emphasis on the worship of the goddess in feminist Wiccan traditions

- The popularization of Wicca and Neo-Paganism through books, magazines, and other media

- The publication of influential books like “The Spiral Dance” by Starhawk and “Drawing Down the Moon” by Margot Adler

- The growth of Pagan and New Age bookstores and the distribution of Pagan-themed merchandise and supplies

- The portrayal of Wicca and Neo-Paganism in popular culture, from “Bewitched” to “The Craft”

- The emergence of Neo-Paganism and Wicca in the United States as part of the countercultural movement

- “Satanic Panic” of the 1980s and the vilification of Paganism and witchcraft in the media

- The rise of conservative Christian groups and the moral panic over alleged Satanic ritual abuse

- The formation of organizations like the “Moral Majority” and the “700 Club” and their campaigns against the “occult”

- The sensationalized media coverage of alleged cases of Satanic ritual abuse, such as the McMartin preschool trial and the West Memphis Three case

- The conflation of Paganism, Wicca, and other alternative religions with Satanism and devil-worship

- The accusations of Satanism and child abuse against Pagan and Wiccan groups by Christian activists and law enforcement

- The misrepresentation of Pagan beliefs and practices in books, films, and television programs about the “occult threat”

- The impact of the “Satanic Panic” on the Pagan and Wiccan communities

- The defensive stance taken by many Pagan groups and the efforts to distance themselves from Satanism and other “dark” practices

- The legal and social challenges faced by Pagans and Wiccans, including custody battles, job discrimination, and harassment

- The long-term effects of the “Satanic Panic” on public perceptions of Paganism and witchcraft and the continued stigmatization of these practices

- The rise of conservative Christian groups and the moral panic over alleged Satanic ritual abuse

- 1990s-2000s: Growth of Pagan festivals and organizations, such as Circle Sanctuary and the Covenant of the Goddess

- The establishment of national and regional Pagan organizations and networks

- The founding of the Covenant of the Goddess (COG) in 1975 as a national association of Wiccan covens and solitaries

- The creation of Circle Sanctuary by Selena Fox in 1974 as a nature spirituality center and Pagan resource hub

- The growth of Pagan festivals and gatherings, such as the Pagan Spirit Gathering and Starwood Festival

- The role of festivals in fostering a sense of community and shared identity among Pagans from different traditions and backgrounds

- The use of festivals as a platform for networking, education, and spiritual development

- The increasing visibility and acceptance of Paganism in mainstream society

- The recognition of Wicca as a legitimate religion by the U.S. military and other government institutions

- The inclusion of Pagan holidays and practices in interfaith dialogues and events

- The growth of Pagan studies as an academic field and the establishment of Pagan seminaries and training programs

- The diversification and evolution of Pagan traditions and practices

- The emergence of new forms of Paganism, such as techno-shamanism and pop culture Paganism

- The influence of other spiritual and cultural traditions, such as Afro-Caribbean religions and Native American spirituality, on contemporary Paganism

- The ongoing debates and tensions within the Pagan community around issues of authenticity, cultural appropriation, and social justice

- The establishment of national and regional Pagan organizations and networks

- Contemporary Pagan activism and social justice work, such as the “Hex the Patriarchy” movement (2010s – present)

- The intersection of Paganism, witchcraft, and social justice activism

- The use of hexes, curses, and other magical practices as forms of political resistance and protest

- The “Hex the Patriarchy” movement and the use of witchcraft as a feminist tool for dismantling oppressive systems

- The involvement of Pagans and witches in environmental and climate justice movements

- The participation of Pagan groups in protests against pipelines, fracking, and other environmental threats

- The use of earth-based spirituality and ritual as a means of fostering ecological awareness and action

- The engagement of Pagan and witch communities with issues of racial justice and decolonization

- The critique of cultural appropriation and the centering of indigenous and marginalized voices within Pagan spaces

- The efforts to confront and dismantle racism and white supremacy within Pagan traditions and organizations

- The impact of social media and online platforms on contemporary Pagan activism and community-building

- The use of hashtags, memes, and viral campaigns to spread Pagan and witch-themed messages and calls to action

- The creation of online forums, groups, and resources for connecting Pagan activists and sharing information and strategies

- The role of social media in amplifying marginalized voices and challenging dominant narratives about Paganism and witchcraft

- The intersection of Paganism, witchcraft, and social justice activism

- Modern American media featuring diverse reinterpretations of the witch archetype, from “Charmed” to “American Horror Story: Coven”

- The portrayal of witches as complex and nuanced characters in contemporary television and film

- The depiction of witches as heroines and protagonists in shows like “Charmed” (1998-2006) and “The Good Witch” (2015-2021)

- The exploration of the dark side of witchcraft and the moral ambiguity of magical power in shows like “American Horror Story: Coven” (2013) and “The Magicians” (2015-2020)

- The representation of diverse identities and experiences within witch-themed media

- The inclusion of LGBTQ+ characters and themes in shows like “The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina” (2018-2020) and “Motherland: Fort Salem” (2020-present)

- The portrayal of witches of color and the incorporation of non-Western magical traditions in films like “Eve’s Bayou” (1997) and “The Craft: Legacy” (2020)

- The use of the witch as a metaphor for female empowerment and resistance in the #MeToo era

- The themes of sisterhood, solidarity, and the reclaiming of power in films like “The Craft” (1996) and its 2020 sequel

- The portrayal of witches as survivors of trauma and abuse who use their magic to heal and fight back, as in the novel “Circe” by Madeline Miller (2018)

- The influence of contemporary Pagan and witch communities on the development and reception of witch-themed media

- The consultation of Pagan and witch practitioners as technical advisors and consultants on films and television shows

- The critique and debate within Pagan and witch communities around the accuracy and authenticity of media representations

- The use of witch-themed media as a gateway and resource for those interested in exploring Pagan and magical practices.

- The portrayal of witches as complex and nuanced characters in contemporary television and film

References

- Beebe, J. (2004). Understanding consciousness through the theory of psychological types. In J. Cambray & L. Carter (Eds.), Analytical psychology: Contemporary perspectives in Jungian analysis (pp. 83-115). Brunner-Routledge.

- Billington, S., & Green, M. (Eds.). (1996). The concept of the goddess. Routledge.

- Estés, C. P. (1992). Women who run with the wolves: Myths and stories of the wild woman archetype. Ballantine Books.

- Friðriksdóttir, J. K. (2020). Valkyrie: The women of the Viking world. Bloomsbury Academic.

- G. (2020). Baba Yaga: The wild witch of the east in Russian fairy tales (S. Forrester, Trans.). University Press of Mississippi.

- Hall, N. (1980). The moon and the virgin: Reflections on the archetypal feminine. Harper & Row.

- Harding, M. E. (1973). Woman’s mysteries, ancient and modern: A psychological interpretation of the feminine principle as portrayed in myth, story, and dreams. G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

- Homer. (1996). The Odyssey (R. Fagles, Trans.). Viking. (Original work published ca. 800 B.C.E.)

- Jung, C. G. (1968). The archetypes and the collective unconscious (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.; 2nd ed., Vol. 9.1). Princeton University Press.

- Kieckhefer, R. (2014). Magic in the Middle Ages (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Moore, R., & Gillette, D. (1991). King, warrior, magician, lover: Rediscovering the archetypes of the mature masculine. HarperSanFrancisco.

- Neumann, E. (2015). The great mother: An analysis of the archetype (R. Manheim, Trans.; 2nd ed.). Princeton University Press.

- Rigoglioso, M. (2009). The cult of divine birth in ancient Greece. Palgrave Macmillan.

0 Comments