How did Psychotherapy Change Over Time?

Timeline of Psychotherapy

Timeline

1890s:

The birth of psychoanalysis with Sigmund Freud

1900s-1910s:

Emergence of competing schools (Adler’s Individual Psychology, Jung’s Analytical Psychology)

Influence of Bleuler

Structuralism vs functionalism debate

1920s:

Expansion of psychoanalysis

Rise of child analysis (Anna Freud, Melanie Klein)

Development of sandplay therapy (Margaret Lowenfeld)

1930s-1940s:

Impact of World War II

Development of ego psychology and neo-Freudian theories

Emergence of existential therapy (Ludwig Binswanger, Medard Boss) and humanistic approaches (Carl Rogers, Abraham Maslow)

1950s-1960s:

Growth of humanistic psychology

Rise of behaviorism and behavior therapy (Joseph Wolpe, Hans Eysenck)

Influence of cybernetics and systems theory

Development of family systems therapy (Murray Bowen, Salvador Minuchin)

1970s-1980s:

Cognitive revolution and the rise of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) (Albert Ellis, Aaron Beck)

Proliferation of new therapies (EMDR, NLP)

Impact of women’s movement and feminist therapy (Carol Gilligan, Jean Baker Miller, Harriet Lerner)

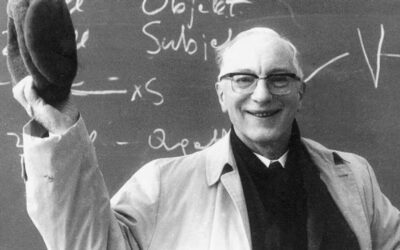

Development of Gestalt therapy (Fritz Perls) and existential therapy (Rollo May, Irvin Yalom)

1990s-2000s:

Integration of Eastern and Western approaches

Rise of mindfulness-based therapies (MBSR, MBCT) (Jon Kabat-Zinn, Zindel Segal, Mark Williams)

Growth of integrative and eclectic approaches

Development of Schema Therapy (Jeffrey Young) and Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) (Marsha Linehan)

2010s-Present:

Impact of technology and social media on psychotherapy delivery and practice

Growing recognition of trauma and development of trauma-informed approaches (Sensorimotor Psychotherapy, Internal Family Systems Therapy) (Pat Ogden, Richard Schwartz)

Ongoing challenges and opportunities

Continued evolution of psychotherapy in response to changing social, cultural, and technological landscape

The Evoloution of Psychotherapy

1890s: The Birth of Psychoanalysis

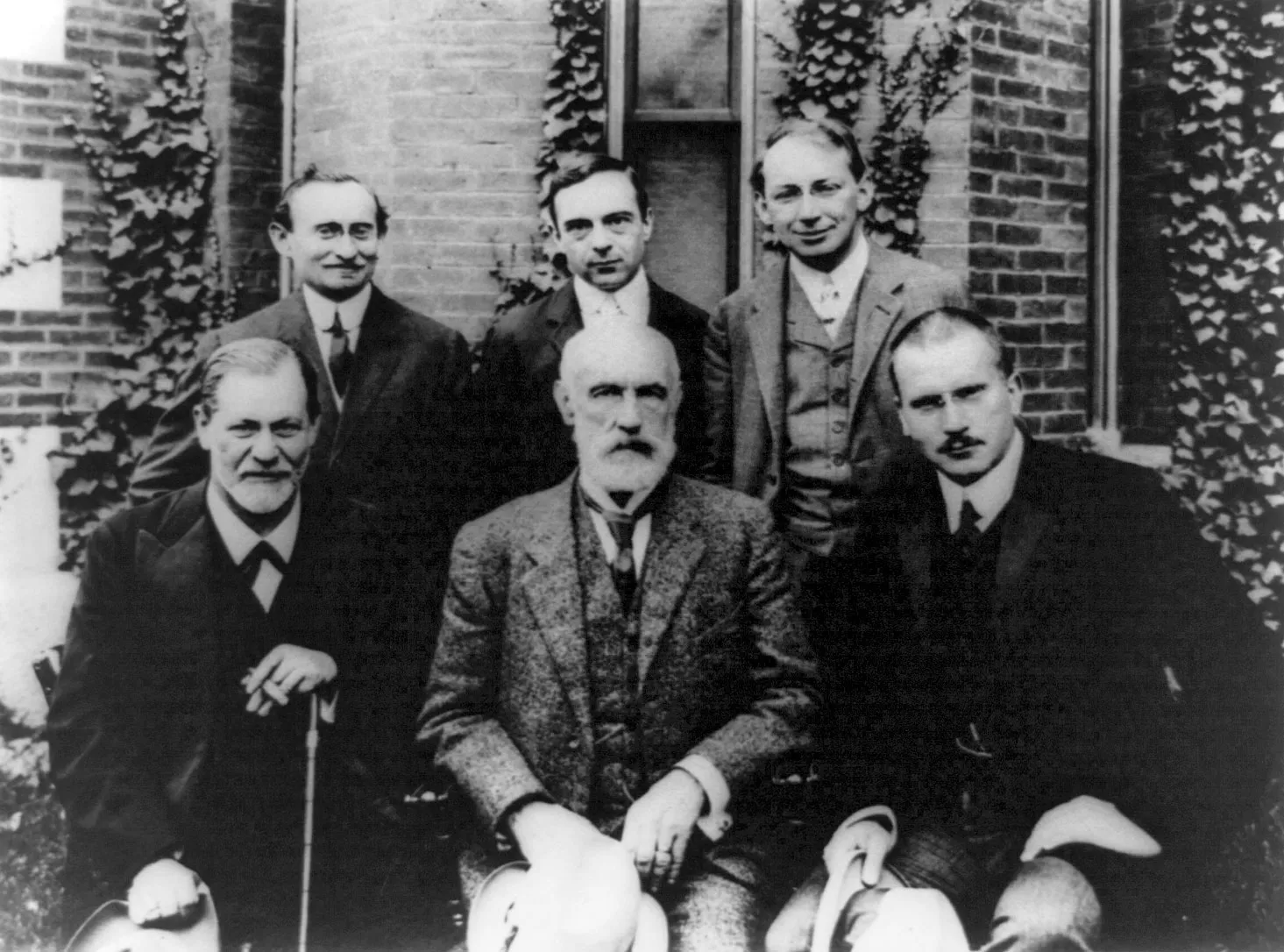

In the 1890s, Sigmund Freud, a Viennese neurologist, began to develop the theoretical foundations of psychoanalysis. Influenced by his collaboration with mentor Josef Breuer on the treatment of hysteria, Freud’s early work focused on the role of repressed memories and unconscious conflicts in the formation of psychological symptoms. This novel approach challenged the prevailing biological and moral explanations of mental illness, suggesting that the root causes of psychological distress lay in the individual’s life history and internal dynamics.

Freud’s ideas, such as the tripartite model of the mind (id, ego, and superego), the importance of early childhood experiences, and the centrality of sexual drives in psychological development, were met with both intrigue and skepticism from the medical community. His emphasis on the unconscious mind and the role of repression in shaping behavior represented a radical departure from the dominant physiological and neurological theories of the time. Many physicians and intellectuals were drawn to the explanatory power of psychoanalytic concepts, while others criticized Freud’s ideas as unscientific, speculative, and potentially scandalous.

Despite the controversies surrounding his theories, Freud’s early work laid the groundwork for the rapid expansion of psychoanalysis in the early 20th century. His ideas resonated with a cultural climate that was increasingly interested in the inner workings of the human mind and the hidden forces that shape individual and social behavior. As psychoanalysis gained traction, it began to attract a devoted following of students and practitioners who would go on to develop and modify Freud’s original insights, setting the stage for the emergence of competing schools of thought within the psychoanalytic tradition.

1900s-1910s: The Emergence of Competing Schools

The development of Alfred Adler’s Individual Psychology (1911) Carl Jung’s break with Freud and the formation of Analytical Psychology (1907) The influence of Eugen Bleuler and the Burghölzli school The debate between structuralism and functionalism in early psychology

The early 20th century saw the emergence of two major challenges to Freudian orthodoxy from within the psychoanalytic movement itself. In 1911, Alfred Adler, one of Freud’s earliest collaborators, broke away to form his own school of Individual Psychology. Adler rejected Freud’s emphasis on sexual drives, instead focusing on the importance of feelings of inferiority and the striving for superiority in shaping personality. He argued that individuals are primarily motivated by a desire to overcome feelings of inadequacy and to achieve a sense of mastery and social belonging.

Similarly, Carl Jung, another of Freud’s close associates, began to develop his own distinctive approach, which he called Analytical Psychology. Jung’s theories emphasized the collective unconscious, a reservoir of shared human experiences and archetypes, as well as the importance of individuation, the process of psychological integration and self-realization. Jung’s interest in mythology, religion, and the occult reflected a broader cultural fascination with spirituality and the search for meaning in the early 20th century. His break with Freud in 1907 marked a significant schism within the psychoanalytic community.

During this period, Eugen Bleuler, a Swiss psychiatrist and the director of the Burghölzli asylum in Zurich, played an important role in the early development and dissemination of psychoanalytic ideas. Bleuler was an early supporter of Freud’s work and invited him to lecture at the Burghölzli in 1908. Bleuler also coined the term “schizophrenia” to describe a group of severe mental disorders characterized by a disconnection between thought, emotion, and behavior. While Bleuler’s conceptualization of schizophrenia was influenced by psychoanalytic ideas about the role of unconscious conflicts and repressed emotions, he also emphasized the importance of biological and genetic factors in the etiology of the disorder.

In the broader field of psychology, the early 20th century was marked by a debate between two competing schools of thought: structuralism and functionalism. Structuralism, championed by Wilhelm Wundt and Edward B. Titchener, sought to analyze the mind into its component parts and to identify the basic elements of conscious experience. Functionalism, led by William James and James Rowland Angell, emphasized the adaptive and purposive nature of mental processes and behavior. While both schools contributed important insights and methods to the study of the mind, functionalism ultimately became the dominant approach in American psychology, paving the way for the development of behaviorism and other applied psychological theories in the early 20th century.

1920s: The Expansion of Psychoanalysis and the Rise of Child Analysis

The growth of psychoanalytic training institutes and societies The development of child analysis by Anna Freud and Melanie Klein The emergence of new therapeutic techniques, such as sandplay therapy

The 1920s witnessed a significant expansion of psychoanalysis as a professional field and a cultural force. The establishment of psychoanalytic training institutes and societies in major cities across Europe and North America helped to standardize training and promote the dissemination of psychoanalytic ideas. This period also saw the rise of lay analysis, the practice of psychoanalysis by non-medical practitioners, which helped to broaden the reach and influence of the field. However, this development also generated controversy and opposition from some medical professionals who viewed psychoanalysis as a threat to their authority and expertise.

One of the most significant developments of the 1920s was the emergence of child analysis as a distinct subspecialty within psychoanalysis. Anna Freud, Sigmund Freud’s daughter, and Melanie Klein, a British psychoanalyst, were at the forefront of this movement. Both developed innovative techniques for working with children, such as play therapy and the analysis of transference and countertransference in the therapeutic relationship. However, their approaches differed in important ways, with Anna Freud emphasizing the role of the ego and the importance of adaptation to reality, while Klein focused on the early development of object relations and the role of fantasy and aggression in shaping the child’s inner world.

The 1920s also saw the emergence of new therapeutic techniques that expanded the scope and application of psychoanalytic ideas. One notable example was the development of sandplay therapy by Margaret Lowenfeld, a British pediatrician and child therapist. Lowenfeld’s approach, which involved the use of miniature figures and objects in a tray of sand, provided a non-verbal means of exploring the child’s inner world and facilitating psychological healing. This period also saw the beginnings of the integration of psychoanalytic ideas with other disciplines, such as anthropology and sociology, as scholars and practitioners sought to understand the broader cultural and social contexts that shape individual development and experience.

1930s-1940s: The Impact of World War II and the Emergence of New Approaches

The forced migration of European psychoanalysts to the United States The development of ego psychology and the rise of neo-Freudian theories The emergence of existential and humanistic approaches to psychotherapy

The 1930s and 1940s were marked by the profound impact of World War II on the field of psychoanalysis. The rise of fascism in Europe and the persecution of Jewish analysts forced many leading figures, including Sigmund Freud and his family, to flee to the United States. This migration had a significant impact on the development of psychoanalysis in America, as European analysts brought their ideas and practices to a new cultural context. The war also led to a growing interest in the psychological effects of trauma and the development of new approaches to the treatment of combat-related disorders.

During this period, the dominant school of psychoanalysis in the United States was ego psychology, which emphasized the role of the ego in mediating between the demands of the id and the constraints of reality. Prominent figures in this movement included Heinz Hartmann, Erik Erikson, and Edith Jacobson, who developed new theories of ego development and adaptation. At the same time, a number of neo-Freudian thinkers, such as Karen Horney, Erich Fromm, and Harry Stack Sullivan, began to challenge some of the basic assumptions of classical psychoanalysis, particularly regarding the primacy of sexual drives and the universality of the Oedipus complex.

The 1940s also saw the emergence of existential and humanistic approaches to psychotherapy, which offered a radical alternative to both psychoanalysis and behaviorism. Influenced by the philosophy of Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre, and others, existential therapists such as Ludwig Binswanger and Medard Boss emphasized the importance of personal responsibility, authenticity, and the search for meaning in the face of the inherent challenges of human existence. Humanistic psychologists, such as Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow, focused on the inherent potential for growth and self-actualization within each individual, and developed new therapeutic techniques, such as client-centered therapy and the hierarchy of needs, that aimed to foster personal development and well-being.

1950s-1960s: The “Third Force” and the Rise of Behaviorism

The growth and development of humanistic psychology The emergence of behaviorism and behavior therapy The influence of cybernetics and systems theory on psychotherapy

The 1950s and 1960s saw the continued growth and development of humanistic psychology, which came to be known as the “third force” in psychology, alongside psychoanalysis and behaviorism. Building on the work of pioneers such as Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow, humanistic psychologists such as Rollo May, Virginia Satir, and Fritz Perls developed new therapeutic approaches that emphasized the importance of authenticity, self-expression, and personal growth. These approaches, which included existential therapy, Gestalt therapy, and family systems therapy, reflected a broader cultural shift towards individualism and self-exploration in the postwar period.

During this period, behaviorism also emerged as a major force in psychology and psychotherapy. Building on the work of John B. Watson and B.F. Skinner, behaviorists such as Joseph Wolpe and Hans Eysenck developed new techniques for the treatment of phobias, anxiety, and other disorders based on principles of classical and operant conditioning. The rise of behaviorism reflected a growing emphasis on scientific rigor and empirical validation in psychology, as well as a reaction against the perceived subjectivity and lack of empirical support for psychoanalytic and humanistic approaches.

The 1950s and 1960s also saw the beginnings of the influence of cybernetics and systems theory on psychotherapy. Developed by mathematicians and engineers such as Norbert Wiener and Claude Shannon, cybernetics provided a new framework for understanding the feedback loops and circular causality that characterize complex systems, including families and other social groups. Family systems therapists such as Murray Bowen and Salvador Minuchin drew on these ideas to develop new approaches to the treatment of relationship and communication problems within families. The influence of systems theory also extended to other areas of psychotherapy, such as the development of brief therapy approaches that aimed to identify and interrupt patterns of dysfunction within larger social systems.

1970s-1980s: The Cognitive Revolution and the Proliferation of New Therapies

The rise of cognitive-behavioral therapy and the integration of cognitive and behavioral approaches The emergence of new therapeutic modalities, such as EMDR and NLP The impact of the women’s movement and the growth of feminist therapy

The 1970s and 1980s were marked by a major shift in the field of psychotherapy, known as the cognitive revolution. Building on the work of pioneers such as Albert Ellis and Aaron Beck, cognitive therapists developed new approaches that emphasized the role of thoughts and beliefs in shaping emotional and behavioral responses. The integration of cognitive and behavioral techniques led to the development of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), which quickly became one of the most widely practiced and empirically validated forms of psychotherapy. CBT reflected a growing emphasis on evidence-based practice and the use of standardized treatment protocols in psychotherapy.

This period also saw the emergence of a wide range of new therapeutic modalities, many of which drew on non-Western spiritual and philosophical traditions. One notable example was the development of Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) by Francine Shapiro, which combined elements of cognitive-behavioral therapy with techniques drawn from Asian meditation practices. Another influential approach was Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP), developed by Richard Bandler and John Grinder, which aimed to identify and modify the linguistic and perceptual patterns that underlie human experience and behavior. These new therapies reflected a growing interest in the integration of mind-body approaches and the exploration of alternative states of consciousness in psychotherapy.

The 1970s and 1980s also saw the impact of the women’s movement and the growth of feminist therapy. Pioneered by therapists such as Carol Gilligan, Jean Baker Miller, and Harriet Lerner, feminist therapy aimed to address the unique psychological and social challenges faced by women, and to challenge the gender biases and power imbalances that characterize traditional approaches to psychotherapy. Feminist therapists emphasized the importance of empowerment, self-determination, and social activism in the therapeutic process, and developed new techniques for working with issues such as sexual trauma, body image, and relationship problems. The influence of feminist therapy extended beyond the boundaries of psychotherapy, contributing to broader cultural conversations about gender, power, and social justice.

1990s-2000s: The Integration of Eastern and Western Approaches and the Rise of Mindfulness-Based Therapies

The influence of Buddhist psychology and meditation practices on psychotherapy The development of mindfulness-based interventions, such as MBSR and MBCT The growth of integrative and eclectic approaches to psychotherapy

The 1990s and 2000s saw a growing interest in the integration of Eastern and Western approaches to psychotherapy, particularly the influence of Buddhist psychology and meditation practices. Pioneered by figures such as Jon Kabat-Zinn and Jack Kornfield, this movement aimed to bring the insights and techniques of mindfulness and other contemplative traditions into dialogue with Western psychology and psychotherapy. The development of mindfulness-based interventions, such as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), reflected a growing recognition of the potential benefits of mindfulness practice for a wide range of psychological and physical health problems.

During this period, there was also a growing interest in integrative and eclectic approaches to psychotherapy, which aimed to combine elements of different theoretical orientations and therapeutic techniques in a flexible and individualized manner. One notable example was the development of Schema Therapy by Jeffrey Young, which integrated elements of cognitive-behavioral therapy, psychodynamic therapy, and attachment theory to address deep-seated patterns of maladaptive thinking and behavior. Another influential approach was Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), developed by Marsha Linehan, which combined cognitive-behavioral techniques with mindfulness practice and dialectical philosophy to treat borderline personality disorder and other complex mental health problems.

The 1990s and 2000s also saw the continued growth and diversification of the field of psychotherapy, with the emergence of new modalities and the integration of psychotherapy with other disciplines, such as neuroscience and evolutionary psychology. The rise of evidence-based practice and the emphasis on accountability and cost-effectiveness in healthcare also had a significant impact on the field, leading to a growing focus on the development and validation of standardized treatment protocols and outcome measures. At the same time, there was also a growing recognition of the importance of cultural competence and the need to adapt psychotherapy to the unique needs and experiences of diverse populations, including racial and ethnic minorities, LGBTQ individuals, and individuals with disabilities.

2010s-Present: The Continued Evolution of Psychotherapy in the 21st Century

The impact of technology and social media on the delivery and practice of psychotherapy The growing recognition of the role of trauma and the development of trauma-informed approaches The ongoing challenges and opportunities facing the field of psychotherapy

The 2010s and beyond have seen the continued evolution of psychotherapy in response to the changing social, cultural, and technological landscape of the 21st century. The rise of technology and social media has had a significant impact on the delivery and practice of psychotherapy, with the growth of online therapy, mobile apps, and other digital tools for mental health. While these developments have the potential to increase access to mental health services and reduce stigma, they also raise important questions about the ethics, efficacy, and limitations of technology-mediated psychotherapy. The COVID-19 pandemic has further accelerated the adoption of teletherapy and other remote forms of psychotherapy, highlighting both the challenges and opportunities of this new modality.

Another important development in recent years has been the growing recognition of the role of trauma in mental health and the development of trauma-informed approaches to psychotherapy. Pioneered by therapists such as Bessel van der Kolk and Judith Herman, this movement emphasizes the importance of understanding the impact of trauma on the brain and body, and the need for therapies that address the underlying causes of trauma-related disorders, such as PTSD and complex trauma. Trauma-informed approaches, such as Sensorimotor Psychotherapy and Internal Family Systems Therapy, aim to help individuals process and integrate traumatic experiences in a safe and supportive therapeutic environment, and to develop new coping skills and strategies for healing and resilience.

As psychotherapy continues to evolve in the 21st century, it faces a number of ongoing challenges and opportunities. One major challenge is the need to address the growing mental health crisis, particularly in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and other global stressors. This will require the development of new and innovative approaches to prevention, early intervention, and treatment, as well as a greater focus on social determinants of mental health, such as poverty, discrimination, and inequality. Another challenge is the need to adapt psychotherapy to the unique needs and experiences of diverse populations around the world, taking into account cultural, linguistic, and socio-economic factors. At the same time, ongoing advances in neuroscience, technology, and other fields offer exciting opportunities for expanding our understanding of the mind and developing more targeted and effective interventions. As the field of psychotherapy continues to grow and evolve, it will be important to balance innovation with rigorous research, ethical practice, and a commitment to the wellbeing of individuals and communities.

References:

Cushman, P. (1995). Constructing the self, constructing America: A cultural history of psychotherapy. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Ellenberger, H. F. (1970).

The discovery of the unconscious: The history and evolution of dynamic psychiatry. New York, NY: Basic Books. Freedheim, D. K., & Weiner, I. B. (Eds.). (2003).

Handbook of psychology, volume 1: History of psychology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. Hergenhahn, B. R., & Henley, T. B. (2013).

An introduction to the history of psychology (7th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning. Norcross, J. C., VandenBos, G. R., & Freedheim, D. K. (Eds.). (2011).

History of psychotherapy: Continuity and change (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Pickren, W. E., & Rutherford, A. (2010).

A history of modern psychology in context. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. Schultz, D. P., & Schultz, S. E. (2011).

A history of modern psychology (10th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

0 Comments