Executive Summary: The Paradox of Pain

The Cultural Denial: We live in a society that pathologizes suffering, treating it as an anomaly to be fixed rather than an inevitable part of the human condition. This denial creates a secondary layer of suffering: the shame of being “broken.”

The Biological Imperative: According to Polyvagal Theory, our nervous systems are wired for co-regulation. Isolation is not just lonely; it is physically dangerous. Vulnerability is the biological signal that invites safety and connection.

The Path to Wholeness: Healing is not about optimization or symptom elimination. It is about integration. By embracing the “Wounded Healer” archetype and practicing radical vulnerability, we move from a fragile perfection to an antifragile resilience.

Why Should I Care About Mental Health? Embracing Vulnerability in a Perfectionist Culture

Our culture often falls short in preparing us for vulnerability. We frequently use technology to create an illusion of perfection, convincing ourselves and others that our lives are flawless and will remain so. This facade, though comforting, is ultimately misleading and sets us up for crises when we inevitably encounter pain and suffering. We curate our online avatars to project success, happiness, and invulnerability, creating a feedback loop of social comparison where everyone believes everyone else is doing better than they are. This digital masquerade is what Jungians call the Persona—the mask we wear to survive social interactions. While the Persona is useful for navigating a cocktail party, it is disastrous for the soul. When we identify too closely with this mask, we lose the ability to handle the inevitable suffering that life brings.

In our society, there is a tendency to isolate the elderly, the sick, and the needy, segregating them from the rest of the community. We hide pain and vulnerability from ourselves and our children, leading to a lack of skills to handle these essential aspects of human existence. We have sanitized our lives to the point of sterility, outsourcing death to hospitals and grief to private therapy rooms, treating these universal experiences as if they were contagious diseases. It’s important to recognize that almost half of the population will experience a mental health issue at some point, and everyone will face periods of grief, confusion, and suffering that require the support of others. Suffering is not an anomaly; it is a baseline statistic of the human condition. To care about mental health is not to seek a state of permanent happiness; it is to build the resilience required to weather the storms that will inevitably come.

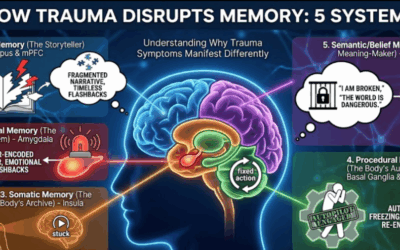

The Biology of Connection: Why We Cannot Heal Alone

There is a pervasive myth in Western culture that mental health is an individual responsibility—a matter of “mindset” or “grit.” We are told to pull ourselves up by our bootstraps, to “manifest” our way out of depression, or to simply think more positively. However, modern neuroscience refutes the idea of the isolated self. According to Dr. Stephen Porges’ Polyvagal Theory, our nervous systems are not self-contained units; they are wireless networks constantly scanning for safety in the faces and voices of others. We are a social species, evolved to regulate our emotional states through interaction with our tribe. When we are isolated, our nervous system interprets this as a life threat, shifting into a state of chronic hypervigilance or collapse.

We are biologically wired for Co-Regulation. When we are vulnerable with a safe person, our nervous system moves out of the “Fight or Flight” sympathetic state and into the “Social Engagement” ventral vagal state. This is where healing happens. When we hide our vulnerability to maintain an image of perfection, we deny our nervous system the signal of safety it craves. We remain in a state of chronic, high-functioning anxiety, scanning for threats that aren’t there. This explains why high-achievers often suffer the hardest crashes; their success isolates them from the very vulnerability that would regulate their stress. They believe that if they just work harder, they will feel safe. But safety doesn’t come from achievement; it comes from connection.

The Wounded Healer Archetype

As a child, I admired many individuals in the helping professions who made a positive impact in their communities. I saw them as stoic heroes, impervious to the pain they helped others navigate. As I grew older and entered the field myself, I realized that their effectiveness and relatability came not from their invulnerability, but from their willingness to speak openly about their struggles and pain. This honesty was refreshing and comforting to those who felt isolated in their own suffering. In depth psychology, this is known as the Archetype of the Wounded Healer (Chiron). The most effective guides are those who have walked the path of suffering themselves and returned with a map.

Pain and vulnerability do not signify weakness. They become debilitating only when we refuse to accept the help we need to become stronger. These experiences are part of what makes us human, and overcoming them makes us more adaptable and better prepared for life’s challenges. The therapist’s authority does not come from having a perfect life; it comes from having navigated the darkness and survived. This is why clinical transparency—admitting when we don’t know the answer or when we have made a mistake—is often more therapeutic than expert advice. It models for the patient that one does not need to be perfect to be worthy of love and respect.

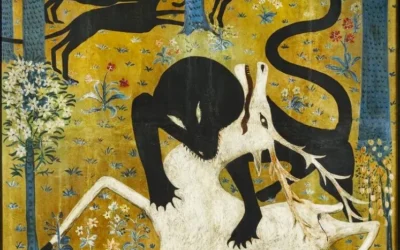

Kintsugi and Post-Traumatic Growth

Accepting that pain is an unavoidable part of life is the first step toward healing. Many beautiful works of art have emerged from processed trauma. Similarly, many people enter healing professions because they have acquired the tools to provide the help they once needed. There is a Japanese art form called Kintsugi, where broken pottery is repaired with gold lacquer. The result is a bowl that is more beautiful and valuable because it has been broken. The cracks are not hidden; they are highlighted.

This is the perfect metaphor for what psychologists call Post-Traumatic Growth. We often view mental health treatment as a way to “get back to normal”—to glue the bowl back together so no one sees the cracks. But true therapy is not about erasing the damage; it is about highlighting the repair. When we process trauma, we do not return to who we were before. We become something new. We integrate the Shadow parts of ourselves—the fear, the rage, the grief—and in doing so, we become more complex, more empathetic, and more grounded. We move from a fragile perfection to an antifragile resilience.

Moving From “Symptom Management” to “Wholeness”

To foster a healthier society, we must be honest with ourselves and others about our vulnerabilities. We need to recognize and address the parts of ourselves that we hide. By doing so, we can better support those in our community who need help. Improving mental health is not just about feeling “better” or eliminating symptoms. It involves learning to embrace and accept the full spectrum of our experiences and parts that make us whole. There is joy, sadness, and profound absurdity in the human condition. Everyone needs help at times, and everyone has the capacity to help others. Recognizing this interconnectedness can help us build a more compassionate and supportive world. When we embrace our own brokenness, we give permission for others to do the same, creating a community bound not by perfection, but by shared humanity.

Bibliography

Brown, B. (2012). Daring Greatly: How the Courage to Be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent, and Lead. Gotham Books.

Neff, K. (2011). Self-Compassion: The Proven Power of Being Kind to Yourself. William Morrow.

Keltner, D. (2009). Born to Be Good: The Science of a Meaningful Life. W.W. Norton & Company.

Gilbert, P. (2010). The Compassionate Mind: A New Approach to Life’s Challenges. New Harbinger Publications.

Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Viking.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-regulation. W.W. Norton & Company.

Becker, E. (1973). The Denial of Death. Free Press.

Jung, C. G. (1959). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton University Press.

0 Comments