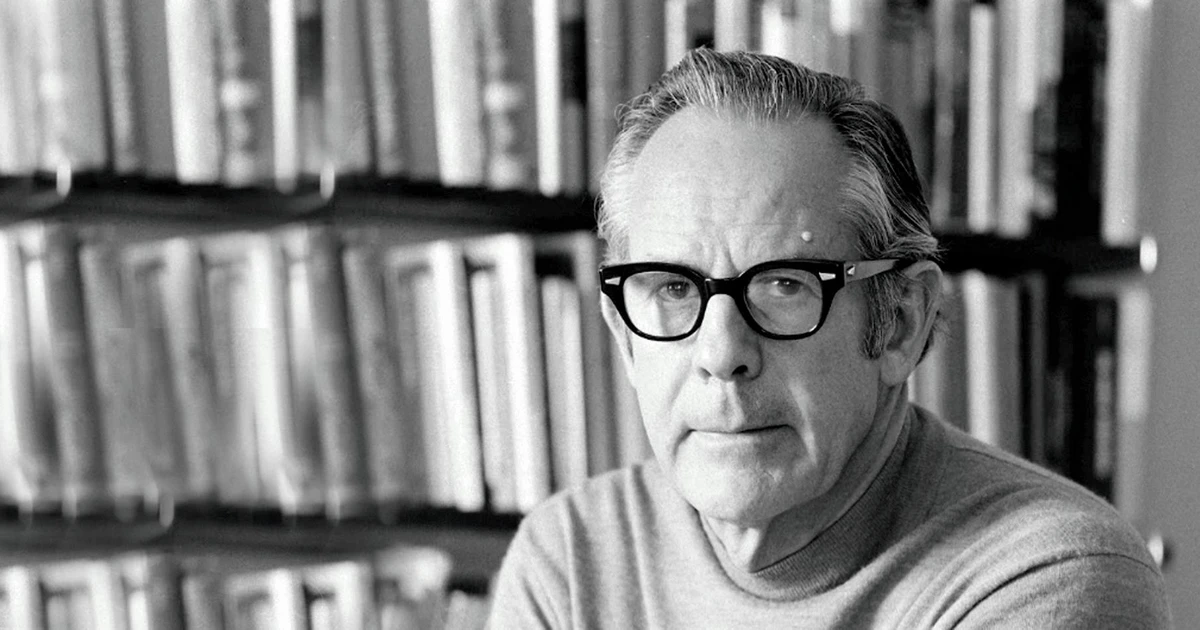

Exploring the Contributions of Rollo May to Existential Psychotherapy

Who was Rollo May

Rollo May (1909-1994) was an influential American existential psychologist and psychotherapist. He played a key role in introducing existential psychology to the United States and in shaping the humanistic psychology movement of the mid-20th century. May’s work bridged the insights of European existential philosophy with the practical concerns of clinical psychology, offering a compelling vision of the human condition and the therapeutic process.

Life and Career

May was born in Ohio in 1909 and grew up in a Protestant family. He earned a bachelor’s degree in English from Oberlin College in 1930 and then spent several years teaching in Greece. This experience sparked his interest in philosophy and psychology, particularly the works of Søren Kierkegaard and other existential thinkers.

In the late 1930s, May returned to the United States to pursue a Ph.D. in clinical psychology at Columbia University. His studies were interrupted by the outbreak of World War II, during which he served as a counselor to conscientious objectors. After the war, May completed his doctorate and began a career as a practicing psychotherapist and academic.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, May emerged as a leading voice in the humanistic psychology movement, which emphasized human potential, creativity, and the search for meaning. He cofounded the Saybrook Graduate School and Research Center, an institution dedicated to humanistic and existential studies, and served as a mentor to many younger psychologists.

May’s major works include The Meaning of Anxiety (1950), Man’s Search for Himself (1953), Existence (1958), Love and Will (1969), and The Courage to Create (1975). He continued to write and lecture until his death in 1994.

Timeline of May’s Life

1909: Born in Ada, Ohio 1930: Earns bachelor’s degree in English from Oberlin College 1930-1933: Teaches English at Anatolia College in Greece 1938: Begins Ph.D. studies in clinical psychology at Columbia University 1942-1945: Serves as a counselor to conscientious objectors during World War II 1949: Completes Ph.D. and begins practice as a psychotherapist 1950: Publishes The Meaning of Anxiety 1953: Publishes Man’s Search for Himself 1958: Publishes Existence, an edited collection introducing existential psychology to American audiences 1960: Helps establish the Saybrook Graduate School and Research Center 1969: Publishes Love and Will 1975: Publishes The Courage to Create 1994: Dies in Tiburon, California

Key Ideas

Existential Psychology: May was a pioneer in bringing the insights of existential philosophy to bear on the practice of psychotherapy. He saw the central task of therapy as helping individuals confront the ultimate concerns of existence, such as death, freedom, isolation

and meaninglessness. For May, psychological distress often stemmed from the avoidance or denial of these existential realities.

Anxiety and Creativity: In works such as The Meaning of Anxiety, May explored the role of anxiety in human existence. He distinguished between normal and neurotic anxiety, seeing the former as an inevitable part of the human condition and the latter as a maladaptive response to existential threats. May also linked anxiety to creativity, arguing that the confrontation with uncertainty and the unknown was essential to the creative process.

Love and Will: May’s 1969 book Love and Will examined the interplay between these two fundamental human capacities. He saw love as the desire for union and will as the capacity for self-assertion and choice. May argued that both love and will were necessary for healthy human development and that the balance between them was often disrupted in psychological disorders.

The Courage to Create: In The Courage to Create, May explored the nature of creativity and the psychological conditions that foster or inhibit it. He emphasized the role of courage in overcoming the anxiety and doubt that often accompany the creative process. For May, creativity was not just an artistic or intellectual pursuit but a fundamental aspect of self-actualization and authentic living.

The Therapeutic Relationship: May saw the therapeutic relationship as the heart of the psychotherapeutic process. He emphasized the importance of the therapist’s presence, empathy, and genuineness in creating a safe and supportive environment for the client’s self-exploration. May also stressed the dialogical nature of therapy, seeing it as a collaborative process in which both therapist and client are transformed.

May’s Conceptualization of Trauma

May’s existential approach to psychology offers a distinctive perspective on trauma and its impact on the human psyche. For May, trauma is not just a discrete event or series of events, but a rupture in the individual’s fundamental relationship to the world. Traumatic experiences shatter the assumptions and beliefs that give meaning and coherence to our lives, confronting us with the existential realities of death, isolation, meaninglessness, and the limits of our own freedom and control.

In works such as The Meaning of Anxiety, May explored the psychological impact of traumatic events such as war, violence, and personal loss. He saw these experiences as existential crises that challenge our basic sense of trust, safety, and identity. Trauma can lead to a profound sense of anxiety and despair, as the individual struggles to reconcile the shattered fragments of their world.

At the same time, May recognized that trauma can also be a catalyst for growth and transformation. By forcing us to confront the ultimate concerns of existence, traumatic experiences can break us out of our habitual patterns and illusions, opening up new possibilities for authentic living. The process of recovery from trauma, in May’s view, involves not just a return to pre-trauma functioning, but a fundamental rebuilding of the self and the individual’s relationship to the world.

May emphasized the importance of meaning-making in the recovery process. Traumatic events often disrupt the narratives and belief systems that give our lives sense and purpose. The task of therapy, in May’s view, is to help individuals construct new meanings and narratives that can integrate the traumatic experience and restore a sense of coherence and continuity to their lives.

This process of post-traumatic growth, for May, is not about finding definitive answers or explanations, but about learning to live with the questions and uncertainties that trauma raises. It involves a willingness to face the existential void, to embrace the anxiety and doubt that come with the shattering of old certainties. By courageously engaging with these existential challenges, individuals can develop a deeper sense of self-awareness, authenticity, and resilience.

Insights from Psychology and Anthropology

May’s existential approach to psychology draws on a rich tapestry of philosophical, psychological, and anthropological insights. His emphasis on the subjective, lived experience of the individual resonates with the phenomenological tradition in philosophy and the humanistic movement in psychology. Like other humanistic psychologists such as Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow, May stressed the inherent potential for growth and self-actualization in every individual.

At the same time, May’s work is deeply informed by existential philosophy, particularly the ideas of Søren Kierkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Martin Heidegger. From these thinkers, May draws a vision of the human condition as fundamentally marked by anxiety, freedom, and the search for meaning in the face of life’s absurdities and limitations. He sees psychotherapy as a way of helping individuals confront these existential givens and develop the courage to live authentically.

May’s understanding of anxiety has been particularly influential in psychology. Drawing on Kierkegaard’s concept of angst and Heidegger’s notion of dread, May sees anxiety as an ontological condition, an inevitable part of being human. He distinguishes this normal, existential anxiety from neurotic anxiety, which is a maladaptive response to the challenges of existence. May’s work has informed subsequent research on anxiety disorders and their treatment.

May’s emphasis on the cultural and interpersonal dimensions of existence also reflects insights from anthropology and sociology. He recognized that individuals are always situated within specific historical, cultural, and social contexts that shape their experiences and understandings. May was particularly interested in the challenges of modernity, the ways in which industrialization, urbanization, and secularization had disrupted traditional sources of meaning and community.

Drawing on anthropological studies of ritual and myth, May explored the role of symbols and narratives in shaping human experience. He saw therapy as a kind of modern ritual, a space in which individuals could explore new meanings and identities. At the same time, he was critical of the conformist pressures of mass society, arguing that authentic selfhood required a degree of resistance to societal norms.

May’s vision of the self as fundamentally relational also reflects anthropological understandings of personhood. Against the Western ideal of the autonomous, independent self, May emphasized the ways in which our identities are formed through our relationships with others. He saw love and will as the two fundamental poles of the self, the capacity for union and the capacity for separation and individuation.

Finally, May’s emphasis on creativity as a fundamental human capacity draws on anthropological studies of art, culture, and innovation. He saw the creative impulse as a key driver of both personal and cultural transformation. By engaging in the creative process, whether through art, science, or everyday life, individuals could transcend their limitations and contribute to the ongoing evolution of human possibilities.

Relevance to Psychotherapy

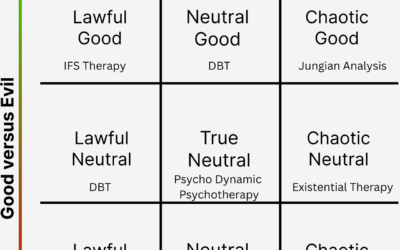

Integrating Existential Themes: May’s work helped to integrate existential themes into the theory and practice of psychotherapy. His emphasis on confronting the ultimate concerns of existence, such as death, freedom, and meaninglessness, expanded the scope of therapy beyond the treatment of specific symptoms or disorders. Therapists influenced by May are attuned to the existential dimensions of clients’ struggles and seek to help them develop the courage and resilience to face these challenges.

Anxiety and Psychopathology: May’s distinction between normal and neurotic anxiety has been influential in the conceptualization and treatment of anxiety disorders. Therapists may work with clients to understand the existential roots of their anxiety and to develop more adaptive ways of coping with the uncertainties of life. May’s insights into the link between anxiety and creativity can also inform therapeutic work with artists, writers, and other creative individuals.

Love, Will, and Relationships: May’s exploration of the dialectic between love and will offers a rich framework for understanding interpersonal relationships and the challenges of intimacy. Therapists may draw on May’s ideas to help clients navigate the tensions between the desire for connection and the need for autonomy. May’s emphasis on the balance between love and will can also inform work with couples and families.

Creativity and Self-Actualization: May’s celebration of creativity as a fundamental aspect of human potential has been influential in humanistic and existential approaches to therapy. Therapists may work with clients to identify and overcome the blocks to their creative expression and to cultivate the courage and resilience needed to pursue their creative goals. May’s ideas can also inform the use of art, writing, and other creative modalities in therapy.

The Therapeutic Relationship: May’s emphasis on the therapeutic relationship as a dialogical encounter has shaped the practice of existential and humanistic psychotherapy. Therapists influenced by May strive to create a genuine, empathetic, and collaborative relationship with their clients, one that can facilitate deep self-exploration and transformation. May’s vision of therapy as a shared journey towards greater authenticity and meaning continues to inspire therapists across theoretical orientations.

Conclusion

Rollo May’s contributions to existential psychology and psychotherapy have left an indelible mark on the field. By bringing the insights of existential philosophy to bear on the concrete challenges of clinical practice, May helped to humanize and deepen the therapeutic enterprise. His emphasis on creativity, courage, and the search for meaning in the face of life’s existential givens continues to resonate with therapists and clients alike.

At the heart of May’s vision is a profound respect for the uniqueness and potential of every individual. He saw therapy not as a technique for fixing disorders, but as a way of facilitating the client’s own growth and self-discovery. By creating a safe and supportive space for exploring the ultimate concerns of existence, therapists can help clients develop the resilience and authenticity needed to navigate life’s challenges and uncertainties.

As the field of psychology continues to evolve, May’s insights remain as relevant as ever. In a world marked by rapid change, dislocation, and the erosion of traditional sources of meaning, the existential questions that May grappled with have only become more urgent. By engaging with May’s ideas and example, therapists can continue to help individuals find their own path towards a more authentic and fulfilling existence.

Key Takeaways

- Rollo May was a pioneering existential psychologist who helped introduce existential themes into American psychotherapy.

- May emphasized the role of anxiety, creativity, love, and will in shaping the human condition and the therapeutic process.

- May’s work drew on a range of philosophical, psychological, and anthropological insights, from existentialism to humanism to studies of art and culture.

- May’s ideas have been influential in the conceptualization and treatment of anxiety, the understanding of relationships and creativity, and the practice of the therapeutic relationship.

- Engaging with May’s vision of therapy as a shared journey towards authenticity and meaning can enrich the practice of psychotherapy and the lives of both therapists and clients.

Bibliography

- The Meaning of Anxiety by Rollo May

- Man’s Search for Himself by Rollo May

- Existence edited by Rollo May

- Love and Will by Rollo May

- The Courage to Create by Rollo May

- The Discovery of Being by Rollo May

- The Cry for Myth by Rollo May

- Existential Psychotherapy by Irvin D. Yalom

- Existential-Integrative Psychotherapy edited by Kirk J. Schneider

- The Psychology of Existence by Kirk J. Schneider and Rollo May

- Anxiety and Self-Focused Attention by R. Schwarzer and Rollo May

- The Meaning of Anxiety by Sal Maddi

- Freedom and Destiny by Rollo May

0 Comments