Where Art Meets Life in the American Landscape

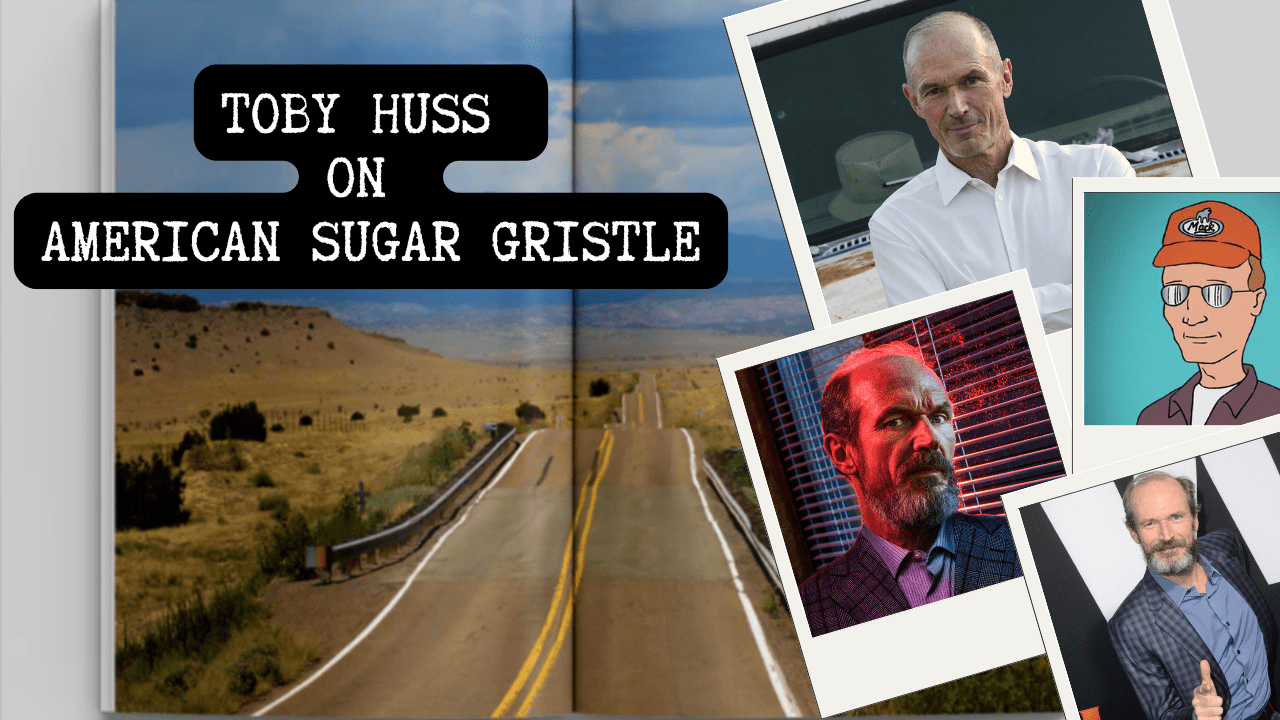

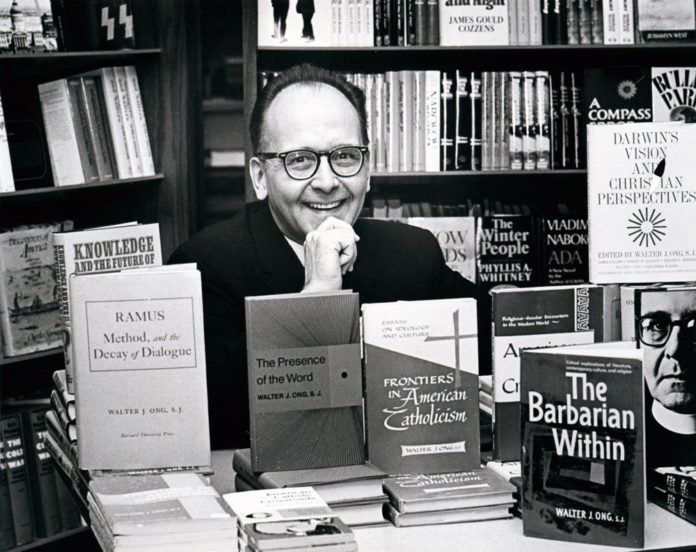

In an era where social media algorithms and political narratives seem determined to divide us, actor and visual artist Toby Huss offers a radically different perspective on American identity. Through his photography book “American Sugar Gristle” and a career spanning from cult classics like “The Adventures of Pete & Pete” to prestige television like AMC’s “Halt and Catch Fire,” Huss has cultivated a unique ability to find profound beauty in the most unexpected places.

This in-depth conversation with therapist and podcast host Joel Blackstock reveals not just an artist’s process, but a philosophy of seeing that challenges our assumptions about art, trauma, creativity, and what it means to truly observe the world around us. From truck stop graffiti to abstract paintings that process trauma, Huss demonstrates how authentic artistic expression can serve as both mirror and medicine for the human experience.

The Connective Tissue of America: Understanding “American Sugar Gristle”

What’s in a Name? Decoding the Title

The title “American Sugar Gristle” immediately evokes something quintessentially American yet difficult to define. As Blackstock notes in the interview, it captures an “Americana feel” while coining something entirely new. Huss explains that the title represents “a connective tissue in America, a non-coastal essence that exists across different regions despite media portrayals of separation.”

The word “gristle” is particularly evocative – it’s the tough, chewy part between meat and bone, neither one thing nor another. It’s not the prime cut, but it’s essential connective tissue. This metaphor perfectly captures Huss’s photographic subjects: the in-between spaces, the overlooked corners, the liminal zones of American life that connect us all despite surface differences.

Beyond the Coastal Bubble: Finding Universal American Experiences

Huss’s work deliberately focuses on non-coastal America, but not in the anthropological “safari” mode that he critiques. Instead, he seeks out what he calls a “uniquely American visual language that transcends regional differences.” This isn’t poverty porn or rural romanticism – it’s a genuine attempt to decode the aesthetic DNA of American places.

“You have to actively seek out this identity rather than passively consuming media narratives of division,” Huss explains. His photographs capture gas stations, strip malls, roadside attractions, and yes, even graffiti – but always with an eye toward what these spaces reveal about the people who move through them.

The Philosophy of Seeing: Training Your Eye for Wonder

From Palmdale to Paris: Legitimizing the Mundane

One of the most compelling aspects of Huss’s artistic philosophy is his insistence that beauty exists everywhere – you just have to train yourself to see it. He shares a transformative experience in Palmdale, California, a place he initially found “aesthetically challenging”:

“I realized that beauty is subjective and that the visual aesthetic one grows up with shapes their perception. This led me on a journey to find beauty in overlooked and liminal spaces.”

This isn’t about romanticizing decay or fetishizing the mundane. Instead, Huss argues for the radical equality of all visual experience. “I believe in training oneself to find beauty in the ordinary, equating the legitimacy of photographing a Parisian street with capturing a unique American scene.”

The Danger of Cynicism in Art

Perhaps most crucially, Huss emphasizes his “deliberate avoidance of cynicism and irony” in his work. In an art world often dominated by knowing winks and intellectual superiority, this stance is almost revolutionary. As he puts it, cynicism “would undermine the genuine wonder I aimed to convey about my subjects.”

This approach extends to his treatment of people across the political spectrum. Rather than creating work that mocks or judges, Huss seeks “the shared humanity he observed across the political spectrum.” It’s not about being apolitical – it’s about finding deeper truths than surface-level divisions.

Photography as Language: Decoding Place Through Image

Capturing Impressions, Not Just Images

Huss describes his photographic approach as a form of “visual language,” but he’s not interested in mere documentation. Instead, he seeks to “capture the impression left on a location by the lives that have passed through it.” This is photography as archaeology of the present moment.

One standout example is his photograph titled “Where They Grow Headstones” – an image from South Carolina that took a year to properly caption. The title’s perfection lies in its ability to transform a mundane scene into something almost mystical, suggesting both mortality and growth, industry and nature.

Technical Mastery vs. Storytelling

When asked about his technical approach, Huss is refreshingly dismissive of gear fetishization. Using a Nikon D800, a Ricoh GR3, and sometimes just an iPhone, he insists that “technical aspects are secondary to storytelling.” He shares a pointed anecdote about a friend’s technically proficient but meaningless photos of a homeless person, emphasizing “the need for intention and purpose behind taking a photograph.”

This philosophy extends to his critique of conventional beauty photography. Recounting a formative experience with Iowa barn calendars, he realized that “simply capturing a beautiful sunset on a barn wasn’t adding anything meaningful to a visual or cultural dialogue.” Every image must contribute something new to the conversation.

The Art of Performance: From Bosworth to Dale Gribble

The Authentic Performativity of John Bosworth

Blackstock observes a recurring “folksy, performative quality” in many of Huss’s roles, particularly his beloved portrayal of John Bosworth in “Halt and Catch Fire.” Huss offers a nuanced perspective on this performance within performance:

“While some characters, like Bosworth in ‘Halt and Catch Fire,’ are intentionally performative due to their profession as a salesman, it’s not always conscious or direct manipulation. These characters often have moments of genuine connection where the performative mask drops.”

This understanding of performance as potentially authentic rather than necessarily deceptive adds layers to Huss’s acting work. Bosworth’s salesman energy isn’t a false front – it’s who he genuinely is, just as some people naturally speak in stories and metaphors.

Taking on Dale Gribble: Honor and Humility

In the 2025 revival of King of the Hill, Huss will voice Dale Gribble, taking over from Johnny Hardwick who passed away in 2023. Huss approaches this responsibility with remarkable humility:

“I expressed humility and honor in taking on this role, emphasizing the unique and irreplaceable nature of Johnny’s portrayal.”

This isn’t just professional courtesy – it reveals Huss’s deep respect for the craft and his understanding that each actor brings something irreplaceable to their roles. His approach to inhabiting Dale won’t be imitation but rather finding his own authentic connection to the character.

The Actor’s Intuition: Knowing Your Character

Huss shares a revealing anecdote about insisting on specific cowboy boots for Bosworth, illustrating the deep, almost mystical connection actors develop with their characters. This extends to his preference for “creative collaborations where intuition is valued” over rigid directorial control.

“The actor has an intimate knowledge of their character, even when working with talented writers and directors,” he explains. This isn’t about ego – it’s about recognizing that inhabiting a character creates a unique form of knowledge that can’t be intellectualized.

Art as Trauma Processing: The Unexpected Journey of Painting

From Abstract Lines to Healing

One of the most fascinating threads in the conversation concerns Huss’s painting practice and its unexpected connection to trauma processing. He recounts having a solo show of line paintings where “the recurring squiggly line in their art had been an unconscious motif for decades.”

The revelation came through therapeutic work: “Toby connected their abstract line paintings to therapeutic MDMA sessions they underwent, suggesting that the physicalized act of painting was a way of releasing stored trauma.”

The Body Knows: Physical Expression of Psychological States

This discovery aligns with current understanding of trauma as stored in the body, not just the mind. Huss’s paintings become a form of somatic expression – the body speaking what the conscious mind cannot yet articulate. Importantly, he notes that “while their work touches on personal trauma, it wasn’t an intentional exploitation of it but rather an exploration of how it manifests physically.”

Blackstock, speaking from his perspective as a clinical social worker, offers valuable insight: “Trauma can bind up intuitive function, requiring one to process the trauma to access the intuition beneath it.” This suggests that Huss’s artistic practices – whether photography, painting, or acting – serve as pathways to accessing deeper truths.

The Graffiti Dialogues: America’s Most Democratic Art Form

Penis Graffiti as Cultural Text

In one of the interview’s most unexpectedly profound segments, Huss and Blackstock discuss the ubiquity of phallic graffiti across American landscapes. Far from juvenile humor, Huss sees this as “a somewhat universal and uniquely American element” worthy of serious consideration.

He shares an anecdote about encountering similar graffiti in Spain, suggesting its cross-cultural significance, and recounts a specific instance of “dick graffiti” on a gas pump that inspired lengthy dialogue in his book. These crude drawings become texts revealing “primal, humorous expressions” of humanity.

The Democracy of Anonymous Expression

What makes graffiti particularly interesting to Huss is its democratic nature – anyone can contribute to this ongoing visual dialogue. Unlike gallery art or professional photography, graffiti represents unmediated human expression. It’s the id of American visual culture, revealing truths that polite society won’t acknowledge.

This extends to his treatment of all vernacular expression in his photographs. Whether it’s hand-painted signs, improvised repairs, or decorative choices, Huss sees these as authentic expressions of human creativity worthy of the same attention given to “high” art.

Spiritual Dimensions: Finding Transcendence in Truck Stops

The Mountaintop in the Mundane

When Blackstock notes the “spiritual undertones” in “American Sugar Gristle,” Huss embraces this reading while clarifying his intent: “The book was not intended as a political statement but perhaps carries a spiritual undertone, focusing on a shared American ideal.”

He elaborates on finding transcendence in unexpected places: “Transcendence can be found in everyday places like a rock shop or even in graffiti.” This isn’t New Age mysticism but rather a practical spirituality rooted in presence and attention.

Training the Eye, Opening the Heart

The spiritual dimension of Huss’s work lies not in explicit religious content but in the practice of seeing itself. By training himself to find beauty in strip malls and truck stops, he’s essentially practicing a form of meditation – a disciplined opening to what is rather than what should be.

This practice has ethical implications. As Huss notes, it requires avoiding the “safari mentality” that treats different parts of America as exotic specimens to be captured. Instead, it demands recognizing the full humanity and dignity of all places and people.

The Creative Process: From Intuition to Expression

Multiple Mediums, Unified Vision

Throughout his career, Huss has moved fluidly between acting, voice work, photography, painting, and writing. When asked about cross-inspiration between these forms, he suggests that “his personal artistic sensibilities influence his various creative endeavors” even without direct crossover.

This multidisciplinary approach isn’t dilettantism but rather different facets of a unified creative vision. Whether he’s embodying John Bosworth, photographing a desolate highway, or creating abstract paintings, Huss is exploring the same fundamental questions about authenticity, beauty, and human connection.

The Importance of the Right Medium

Huss emphasizes the importance of questioning “the chosen medium for artistic expression.” Not every idea belongs in every medium. A photograph captures something different than a painting, just as stage acting differs from film work. The artist’s job is to match message to medium.

He notes that different mediums also allow different relationships with time. “Film has a finite timeframe,” while “stage and longer-form television allow more time for character exploration.” Understanding these differences allows for more intentional creative choices.

Professional Insights: Upcoming Projects and Future Directions

“Americana” and “Weapons”: New Frontiers

Huss mentions two films coming out in August: “Americana,” an indie thriller involving a Native American ghost shirt, and “Weapons,” described as a dark and hypnotic thriller from the director of “Barbarian”. These projects suggest Huss’s continued interest in distinctly American stories that probe beneath surface appearances.

The mention of a Native American ghost shirt in “Americana” particularly resonates with themes from “American Sugar Gristle” – objects and places that carry the impressions of history and meaning beyond their physical presence.

The Evolution of a Career

From his breakout role as Artie, the Strongest Man in the World on Nickelodeon’s “The Adventures of Pete & Pete” to his voice work on “King of the Hill” as Cotton Hill and Kahn Souphanousinphone, Huss has built a career on finding depth in seemingly simple characters. His photography and visual art represent not a departure from this work but a deepening of the same investigative impulse.

Therapeutic Dimensions: Art, Healing, and Alternative Modalities

The Growing Acceptance of Alternative Healing

The conversation touches on the increasing mainstream acceptance of alternative therapeutic modalities, from MDMA-assisted therapy to brain spotting and Emotional Transformation Therapy (ETT). Huss notes “a growing cultural openness to alternative modalities like MDMA therapy, which can broaden perspectives.”

This openness parallels the expanded vision Huss brings to his photography – just as we’re learning to see healing in previously dismissed practices, we can learn to see beauty in previously dismissed places.

The Artist as Wounded Healer

Though not explicitly discussed in these terms, Huss embodies the archetype of the wounded healer – someone whose own journey through difficulty qualifies them to guide others. His art doesn’t preach healing but rather demonstrates it through the transformed vision it offers.

Whether processing trauma through abstract painting or finding beauty in forgotten corners of America, Huss shows how creative practice can be therapeutic without being therapy. It’s healing through doing rather than talking.

Cultural Commentary: Beyond Red and Blue

Rejecting the Safari Mentality

One of the most politically relevant aspects of Huss’s work is his explicit rejection of what he calls the “safari mentality” – the tendency of coastal elites to document “flyover country” with condescension or false empathy. This approach, whether from the left or right, treats fellow Americans as exotic others rather than complex humans.

Instead, Huss advocates for what might be called radical presence – being fully where you are without judgment or agenda. This doesn’t mean ignoring real differences or injustices, but rather starting from a place of shared humanity.

The Politics of Attention

In our attention economy, choosing where to direct our gaze is inherently political. Huss’s choice to photograph truck stops and strip malls rather than conventionally beautiful subjects is a form of democracy in action – asserting that these spaces and the people who inhabit them deserve the same quality of attention given to any subject.

This extends to his treatment of class in his acting work. Characters like John Bosworth could easily be played as caricatures, but Huss finds their full humanity, showing how people navigate systems larger than themselves while maintaining dignity and authenticity.

Lessons for Creatives: Practical Wisdom from a Multidisciplinary Artist

Trust Your Intuition (But Do the Work)

Throughout the interview, Huss emphasizes the importance of intuition in creative work while also stressing discipline and craft. Intuition isn’t an excuse for laziness but rather the reward for deep preparation and practice.

His story about insisting on specific boots for Bosworth illustrates this balance – the intuition was correct, but it came from deep character work and understanding, not mere whim.

Find Your Own America (Or Wherever You Are)

While Huss’s work is specifically American, the principle applies universally: wherever you are, there’s unexplored visual and emotional territory waiting for someone with the patience and vision to truly see it. You don’t need to travel to exotic locations – the exotic is hidden in the familiar.

Avoid Cynicism Without Being Naive

Perhaps the most challenging aspect of Huss’s philosophy is maintaining wonder without naivety. He’s clearly aware of America’s problems and divisions, but chooses to focus on connection rather than separation. This isn’t ignorance but rather a strategic choice about what kind of art he wants to add to the world.

Let Different Mediums Teach You Different Things

Huss’s multidisciplinary practice isn’t about being a Renaissance man but about letting different forms of expression access different truths. Photography teaches presence, acting teaches empathy, painting teaches the wisdom of the body. Each medium is a different door into understanding.

The Road Trip as Metaphor: Movement and Seeing

“Paris, Texas” and the American Journey

When Blackstock compares “American Sugar Gristle” to a road trip reminiscent of films like “Paris, Texas,” he touches on a deep American metaphor. The road trip isn’t just about covering distance but about the transformation that comes from sustained attention to the journey itself.

Huss’s photographs capture this sense of movement even in still images – they’re waypoints on an ongoing journey rather than final destinations. Each image suggests what came before and what might come after.

The Discipline of the Journey

Like any real road trip, Huss’s photographic journey requires patience with long stretches of seeming emptiness. The discipline lies in maintaining attention even when nothing seems to be happening, trusting that significance will reveal itself to the patient observer.

Conclusion: The Revolutionary Act of Authentic Seeing

In an era of Instagram filters and curated realities, Toby Huss’s “American Sugar Gristle” stands as a testament to the revolutionary potential of authentic seeing. By refusing cynicism, embracing the mundane, and finding beauty in forgotten corners, Huss offers more than just pretty pictures or entertaining performances – he offers a way of being in the world.

The conversation between Huss and Blackstock reveals an artist who has found coherence across multiple mediums by maintaining a consistent vision: that every person, place, and moment contains potential beauty and meaning if we’re willing to truly look. Whether through the lens of a camera, the body of a character, or the movement of a paintbrush, Huss demonstrates that creative expression at its best is an act of profound attention and care.

For fellow artists, Huss’s work offers permission to trust their own vision even when it doesn’t align with current trends. For everyone else, it’s an invitation to look more carefully at their own surroundings, to find the American Sugar Gristle – that tough, sweet connective tissue – that binds us all together despite surface differences.

In a time when we’re told daily how divided we are, Huss’s quiet insistence on finding connection and beauty in the most unlikely places feels like both balm and challenge. The America he shows us isn’t prettier than the one we know, but it’s more complete, more human, and ultimately more true. And in that truth lies the possibility of healing – for the artist, for the viewer, and perhaps for the culture itself.

As we move forward in an increasingly polarized world, Huss’s example suggests that the way forward might not be through grand gestures or political statements but through the simple, radical act of paying attention. In every truck stop, strip mall, and forgotten corner lies a story waiting to be seen. The question is: are we willing to look?

Tags: Toby Huss interview, American Sugar Gristle, photography art, Halt and Catch Fire, King of the Hill voice actor, trauma and art therapy, creative process, American identity photography, John Bosworth character, Dale Gribble voice, visual storytelling, actor photographer, liminal spaces art, vernacular photography, artistic intuition

0 Comments