Is There a Psychology to Architecture?

Did you enjoy this article? Checkout the podcast here: https://gettherapybirmingham.podbean.com/\

Key Ideas:

- Frank Lloyd Wright’s architectural philosophy centered around creating harmony between nature, structure, and the spiritual and symbolic lives of the building’s inhabitants. His organic architecture aimed to blend buildings seamlessly into their natural surroundings.

- Wright believed form should follow function, meticulously designing spaces to serve the practical needs of occupants while optimizing comfort, efficiency and the human experience. Spatial arrangement, circulation, natural light, and human scale were carefully considered.

- Wright incorporated complex patterns and symbolism, often inspired by nature, geometry, and culture, to engage viewers on a deeper level. These motifs created visual harmony and evoked a dialogue between the built environment and human spirit.

- Wright’s design process relied on seeing and listening to the patterns in the natural world, human life, and artistic/spiritual aspirations. He taught students to intuitively tune into the essence and geometry underlying natural forms.

- Rather than adhering to formal architectural education, Wright valued subjective experience, intuition and an innate understanding of the environment. He criticized the rigidity of academic institutions.

- Wright used mathematical principles like the golden ratio to determine harmonious proportions that felt in tune with nature, without strictly adhering to classical styles. He jumped off from classicists’ assumptions in his own creative directions.

- Wright falls somewhere between classicism and modernism. He broke from excessive ornamentation and rigid symmetry of classicism, but maintained roots in natural principles. He embraced new technologies and functionality like modernists, yet still incorporated organic, cultural and spiritual meaning.

- The meaningful patterns, handcrafted elements, and collaborative building process central to Wright’s approach have become rare in modern prefabricated architecture. Economic factors make his holistic, intuitive design process difficult to replicate today.

- Beyond just functionality, Wright saw architecture as the intersection of the human, natural and metaphysical realms. His buildings were like altars holding the interplay of these sacred forces, demonstrating how the built environment shapes human life and spirit in profound ways.

- Wright infused his structures with deep symbolic meaning connecting to nature, culture, emotions and the human soul. Architecture has the power to enrich human experience by tapping into the collective humanity and unconscious intuition.

I mention Frank Lloyd Wright on here quite a bit and several people have reached out to me to ask me why. What is it that I see in Wright’s work as an inspiration outside of just the realm of architecture. It’s not an easy answer, I am much more interested in Wright’s process than his buildings. I see it as something relevant to al fields of psychology and design. There are “hard” answers and “soft” answers in psychology. Hard answers are objective things like “penicillin cures infection” or “The randomized controlled trial shows this technique is the most effective for the most people”.

I mention Frank Lloyd Wright on here quite a bit and several people have reached out to me to ask me why. What is it that I see in Wright’s work as an inspiration outside of just the realm of architecture. It’s not an easy answer, I am much more interested in Wright’s process than his buildings. I see it as something relevant to al fields of psychology and design. There are “hard” answers and “soft” answers in psychology. Hard answers are objective things like “penicillin cures infection” or “The randomized controlled trial shows this technique is the most effective for the most people”.

Soft answers are more subjective and less testable. When Bessel Van der Kolk says “Neuroscience research shows that the only way we can change the way we feel is by becoming aware of our inner experience and learning to befriend what is going inside ourselves.” that is a very soft answer. We are not able to run a lab test to see what models of therapy help us befriend our inner experience. Instead we need need to to use intuition, nuance, and contextual understanding to feel the spirit, not the letter, of what therapy modalities are doing. Soft sciences are more interesting to me because you are always trying to hit a moving target. With soft science the work of “getting it right” is never quite done. Art is never done goes the quote. We just stop in nice places.

Design is something that will always be a soft science. We will never build the perfect house or create the definitive couch. Design is a continuous process of trying to hit something just on the other side of the horizon. Wright had a way of seeing and listening that I think made him one of the most effective architects of this or any era, but what exactly was that. It is probably easier to say what Wright was NOT than what he was. Wright was not a good guy. Despite his talent as an architect, Wright was erratic and indefensible as a person. A narcissist, serial adulterer, liar, mean spirit, inveterate overspender and just kind of a bad dude. Many times a person’s biography shows clues as to the makeup of their vices. Wright’s biography shows none. Wright was brilliant and in places prophetically influential and he knew it. He had a massive superiority complex and never integrated his gifts as an artist into any semblance of a coherent or healthy psyche. He did experience tragedy as an adult. That is sad but it was much too late to account for the consistently disordered personality already well documented and developed by that time.

Wright was also not always a great architect. Some of his buildings just don’t work. Some of his revival periods are too cold and his forays into modernism too alien to the way people actually live. Some of his experimentation never paid off, but when he was on he was really on. So what makes Wright such a mandatory design reference point? Again there are hard answers in hard sciences and soft answers in soft sciences like design. We know, but we don’t always know why we know. We can not describe why timeless design works in an objective way because the origin of good design lies in the intuitive unconscious mind that dwells beneath language.

The three key points that Wright’s designs revolve around are the natural spaces his designs inhabit, the material function and purpose of the structure, and the symbolic and spiritual lives of the people who inhabit his buildings.

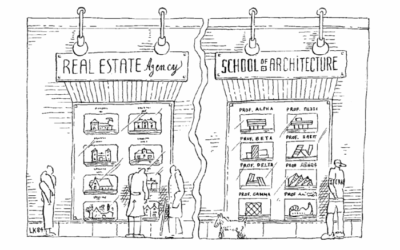

Organic Architecture: A Harmony Between Nature and Structure

At the core of Frank Lloyd Wright’s style lies the concept of organic architecture. He believed that buildings should emerge naturally from their surroundings, blending seamlessly with the environment. Wright’s structures sought to enhance the beauty of the site, integrating with the landscape rather than imposing upon it. By employing materials and colors that mirrored the natural world, he established a harmonious connection between built forms and their settings. His designs often featured horizontal lines at angles that mimicked the horizons of the surrounding geography, organic curves that echoed the surrounding hills, and local materials like stone and wood that embraced the textures of surrounding nature. Through these elements, Wright aimed to create spaces that felt like a continuation of the natural environment, inviting inhabitants to establish a profound holistic connection with their surroundings.

Function as the Driving Force of Design

For Wright, form followed function, an idea he championed with great fervor. He perceived buildings as functional entities, meticulously designed to serve the needs of their occupants. The spatial arrangement, circulation patterns, and integration of natural light were carefully considered to optimize the user experience. Wright’s approach emphasized the human scale, creating spaces that fostered comfort, efficiency, and a profound sense of harmony. By meticulously studying the daily routines, habits, and interactions of his clients, he ensured that his designs met their specific requirements. This approach allowed him to create spaces that seamlessly integrated with the lives of the inhabitants, promoting a sense of well-being and enhancing their overall quality of life.

Patterns: Meaning and Symbolism

Frank Lloyd Wright believed that architecture should go beyond its utilitarian purpose and engage the viewer on a deeper level. One of his distinctive design elements was the incorporation of patterns with complex meanings and symbolism. By infusing his structures with repetitive motifs, Wright sought to create a sense of continuity and coherence. These patterns often drew inspiration from nature, geometric shapes, or cultural symbols, evoking a dialogue between the built environment and the human spirit. The repetition of patterns throughout a structure created a rhythm and visual harmony, connecting various spaces within a building and establishing a cohesive whole. These patterns not only added aesthetic complexity but also contributed to the psychological and emotional experience of the inhabitants.

Design as Intersection of Human Spheres and Natural Planes:

One of the things that is interesting about Wright’s spaces is that he didn’t really design them. We think of an architect as the person who takes out a blank sheet of paper and draws something pretty, but that was not at all what Wright did. Instead he “listened” to the 3 elements of what he saw as the purpose of architecture. The natural, the human, and the spiritual; Wright’s buildings became focal points to synthesize these things. He tried to find the best way that these conflicting forces could be brought together through design. Good design will always be the wresting together of conflicting forces and limitations. He eschewed fads and conventions in design. This is why his process resulted in timeless messages one can still “hear” as you stand in his spaces.

Even though Wright was a narcissist he didn’t really take credit for this intuitive design process. He viewed it as a natural part of our humanity available to anyone who was willing to listen. He taught his process to many students and interns at his Taliesin school and office. Wright viewed formal education and instruction as an obstacle to this kind of intuition and preferred to teach students his process himself before they were corrupted by institutional education. This profited him immensely as his students and draftsmen were often paid little or nothing even though they designed large parts of his completed works. In some cases Wright even had the students working for him pay HIM to design his buildings. Even though he didn’t take credit for his design process he had no problem taking the money and credit from others’ work.

An example of Wright’s process can be found in the excerpt from his architectural school at Taliesin. When you read it you can see how formal education and training would be an obstacle, not an asset, to someone who viewed architecture as a natural outgrowth from the shamanicly experiencing the fusion of the natural, human and spiritual world.

Assignment from the Taliesin School:

Prepare a geometric study of any Wisconsin wildflower endeavoring to get at the essence of its inherent character. Organize this pattern into a design structured upon a unit system. Strive to establish a grammar which will be an inseparable consequence of the design element and unit system. Grammatical pattern must be consistently of the same source and of the same direction from that source. On a separate overlay, isolate the geometric unit system in linear pattern only. Know the common name of the wildflower and bring a few of the flowers to class.

Every design worth considering as a work of art must have a grammar of its own. “Grammar,” in this sense, means the same thing in any construction – whether it be of words, or of stone or wood. It is the shape-relationship between the various elements that enter into the constitution of the thing. Your work must be consistently grammatical for it to be understood as a work of art.

Grammar may be deduced from some plant form that has appealed to me as certain properties in line and form of the sumac were used in the Dana house in Springfield. The motif is adhered to throughout the building.

All my planning was devised on a properly proportional unit system. I found this would keep all to scale, ensuring consistent proportion throughout the design, which thus became – like tapestry – a consistent fabric woven of interdependent, related units, however various . . . Invariably it appears in Organic architecture as a visible feature in the fabric of the design – insuring unity of proportion. The harmony of texture is thus, with the scale of all parts, within the complete ensemble.

Let us learn to see within, at least far enough to grasp essential patterns in all created things. Method in creation will come freely to him who learns to see in the abstract. Study the geometry that is the idea of every form: a quail, a snail, a shell, a fish. Take for analysis the more simple, obvious things first.

Then take the texture of the trees.

Learn the essential pattern that makes the oak and distinguish it from the essential pattern that makes the pine.

Then make new ones. Try after this, the curling vine, flowing water, curving sand.

Then try the flowers, butterflies, and bees.

A Chrysanthemum is easy.

A rock or rose is difficult.

And I do not mean to take the obvious surface effects that differentiate each, but to go within to find the essential geometry of pattern that gives character to each. That is the proper study for an architect who would find method and get legitimate “effects.”

Try this method and gradually discipline your power to see. Get patiently to the point where you naturally see this element of pattern in everything.

– Frank Lloyd Wright

Look at the native Wisconsin wildlife and the impressionistic patterns Wright taught his students to draw from them . Look at the way they apply these theories. This is a beautiful expression of organic design. The representation of the image is distorted enough that if you stood in a space that included this pattern you might not notice the pattern represented tigerlilies outside the building. You deep brain would feel that connection though. Wright did not believe in the mathematical symmetry of a buildings proportions. He did however believe in a spiritual symmetry of space and meanin

Applying that kind of intuitive depth process to any type of art or life is such a beautiful exercise. Wright applied it to his architecture but never to his own life. We should strive to do both.

Frank Lloyd Wright as an Outsider Artist:

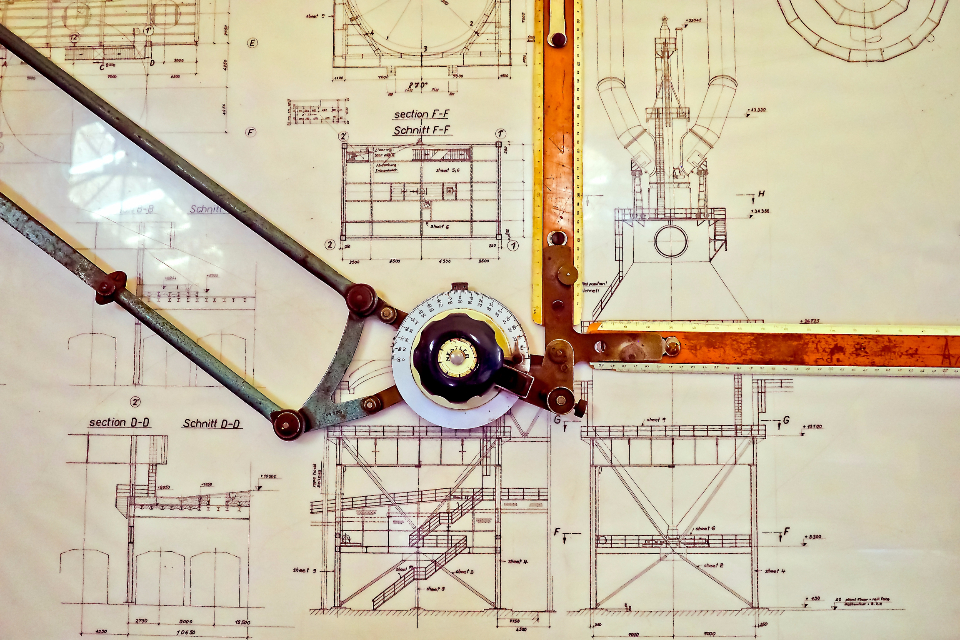

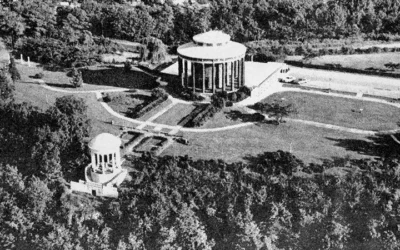

Wright believed that true architectural genius came from subjective experience, intuition, and an innate understanding of the environment, rather than formal education. One of the reasons Wright considered himself an outsider architect was his refusal to conform to the academic norms and traditional architectural education. He had a brief stint at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, but he left without completing his degree, feeling that the academic environment stifled his creative freedom. Could he have designed beautiful spaces like the ones pictured if he had stayed and gotten a PhD in architecture from “experts in beaux arts style? I think not.

Wright’s disdain for academia extended beyond his personal experiences. He criticized architectural schools and institutions for promoting an outdated, formulaic approach to design that focused more on aesthetics and historical imitation rather than innovation and functionality. He saw these institutions as inhibiting the development of truly original and meaningful architectural solutions. He wanted architecture to focus on the people of the now and the future not the empires of old.

Wright created buildings that were not only functional but also contributed to the overall well-being and happiness of their occupants by making their routines more efficient. He saw the traditional floor plans and ornamentation of popular styles of the time, like beaux arts, as hindrances to this. These styles were based on European royals advertising their station and communicating prestige. Wright saw these things as superfluous to the middle class in America and eschewed them in favor of things that elevated what American families actually valued.

What we can Learn from Frank Lloyd Wright:

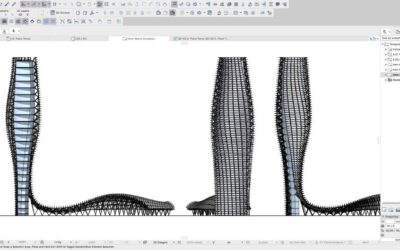

Even the modernists that claim to be carrying on Wright’s legacy have discarded the essence of Wright’s lessons. Most architects and designers of today know that Wright is famous but they seem to have forgotten why. Or maybe they just don’t want to learn. Architects like Frank Gehry design crazy shapes made possible with 3d rendering that are very hard to build or live in. They like auto cad and Revit more than nature, humans or spirituality. Wright’s Guggenheim has a non-traditional form but that was merely the byproduct of Wright listening to and fusing the concrete, glass and bustling pace of movement from the city setting with the spiritual purpose and practical needs of an art museum. The design makes it clear to visitors the path to take intuitively, illuminates common spaces with natural light, shield spaces housing art from direct sunlight, and draws the eye upward like a cathedral to creativity. It is a synthesis of setting spiritual and function.

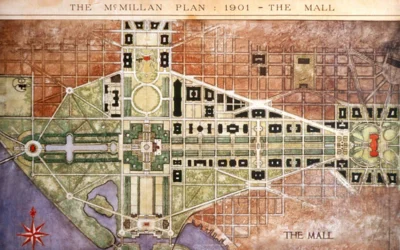

Wright’s work is not a part of classical architecture, in that it does not repeat Greek and Roman ornamentation for the sake of repetition or repeat post renaissance styles simply to associate with a motif. It does however honor the aspirations of classical and renaissance architects to use mathematically derived proportions to determine layouts and structure. This is a strange omission among all the classical architects that decry Wright as a harbinger of the end of their style. Wright based many of his designs on the same principles that renaissance and classical architects had used to determine their style, except he did not emulate the styles they created. Wright’s use of the golden ratio can be observed in various aspects of his designs, including the proportions of rooms, the placement of windows and doors, and the overall composition of buildings. He used it on a more macro level to spiral landscape architecture, ramps and pathways outside of his buildings around the structure into nature. He saw the golden ratio as a tool to create harmonious and visually balanced spaces. He used the golden mean to determine proportion. These are concepts from classical architecture but Wright used them to determine his own style not replicate a historic style.

Wright’s understanding of the golden ratio went beyond mere mathematical calculations. He believed that this ratio, derived from the Fibonacci sequence, had a deeper connection to the natural world and human perception. By incorporating the golden ratio into his designs, Wright aimed to create environments that felt in tune with the inherent mathematical order found in nature. By applying the golden ratio, Wright was in conversation with natural proportion in a way that felt visually pleasing to inhabitants of his structures on an unconscious level. One example of Wright’s use of the golden ratio can be seen in the layout of Fallingwater, one of his most famous residential designs. The proportions and positioning of the various elements, such as the cantilevered balconies and the relationship between interior and exterior spaces, demonstrate an inherent sense of balance and harmony that can be attributed, in part, to the application of the golden ratio and Fibonacci sequence. Wright created his own style from the mathematical variables and assumptions of the classicists but took it a different than the interpretation of the ancient traditions they followed. I don’t view Wright as a part of either classicism or modernism but as a pioneer disregarding modernism of his era and also filtering the classicism what the institutions of his time were teaching.

Without disobeying classical principals Wright could never have engaged with the cantilevered structure that made Fallingwater so famous. It’s asymmetry is what makes it mimic nature and natural proportion that inspired classical mathematics. Classicism prides it self on symmetry based on the fundamentals of mathematics but ignores where those same fundamentals point to asymmetrical designs that Wright discovered when he applied the same mathematical formulas to his own theories. I see Wright’s work as not fully engaging in modernism, but instead using classicists assumptions to develop a new style based on the assumptions that Greeks, Romans, and renaissance artists had used to develop their own styles in the past. If you drew a “tree” of the divides in the schools of architecture I do not see Wright being associated with the free association lists like Gehry towards the top. I think that Wright has more in common with early classicists than the modernists of the contemporary period. He used the assumptions underpinning the classical styles to jump off in his own direction. My take is that Wright essentially a renaissance artist that applied modern politics, economy, and manufacturing principles to the same assumptions as the classical architects. This is why he is misunderstood by classicists and modernists alike. Aristotle and Brunelleschi could not have imagined American society. Wright could see its trajectory and applied their logic as an antidote to our current reality.

What went wrong with modernism?

I still remember wincing when I was walking through one of Frank Gehry’s structures. Elements, shape and scale seemed like they had been selected at random. The strange shape of the outside meant that there were reams of wasted, purposeless, useless space in every room. You might have been able to make a case this was some kind of purely aesthetic point if the artist had read the building codes. Legally required handrails and cane bumpers for the visually impaired had been added during construction taking away any visual symmetry and flow. Additionally these code requirements made the building clunky to navigate casually for most pedestrians.

Gehry’s meandering sheet metal forms felt restrictive and unnatural, nothing like the organic flow and spiraling elevation of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim. Gehrys design decisions feel arbitrary and his structure clashes against the way we use space as humans and the natural world itself. This would be fine as the set of a scifi or as a Salvatore Dali painting but it is not architecture. Looking around you could see visitors conforming to the building, not the other way around. People step around awkward structure that interrupts natural flow. We were not meant to think about art in this museum we are supposed to marvel at the architect. Even as a work of sculpture Gehry’s building failed. Instead of listening to the needs of the natural, spiritual or human world Gehry had listened only to himself, creating a study in self indulgence.

This is what is so frustrating about the way that others talk about Wright’s legacy. The man was a raging narcissist with a personality disorder a mile long; AND STILL even the egomaniac Wright could get his ego out of the way enough to build a space for the site and the people on it. Wright made his life a monument to his own ego, but even he did not make his building monuments to it. Modern architects that view themselves as continuing Wright’s legacy seem to take away from Wright that you should eschew all convention, defy all expectations in design, and make architecture a bunch of weird shapes.

Weird shapes were never Wright’s point at all. There was a subtle language to his deigns and he only broke with tradition in service of higher ideals. Current modernist buildings want us to bend our humanity around their designs. Wright’s designs listened to the intersection of the needs of the human, the natural space and the harmony of those elements. Wright’s buildings were fulcrums that allowed the joint souls of mankind and the natural world to balance against. Wright’s style was not about throwing away tradition or historic style but instead about reclaiming the original intentions of design and centering design on the people of today not the traditions of the past. Wright only discarded tradition as an outgrowth of creating the most efficient way to achieve the practical and spiritual function of the space.

Classicism and Modernism in Wright

Classicism and modernism are two significant architectural movements that have shaped the built environment over the centuries. They are the schools where the most disagreements between architects take place. Classicism, with its roots in ancient Greek and Roman architecture, emphasizes proportion, symmetry, and a sense of order. Tradition and repeating the history of design classicism main goals. Modernism, on the other hand, emerged as a response to the industrial age and sought to embrace new materials, technologies, and a departure from traditional ornamentation. Modernists discard tradition to create new things. Modernism uses new manufacturing techniques and materials to build things that might not have been possible before.

Wright, gets lumped in with the modernists because he used flat roofs, asymmetrical geometry and threw out traditional floor plans and decorative elements. Wright embraced new materials, technologies, and construction techniques, and his designs prioritized functionality. Wright explored innovative building systems and construction techniques in his Usonian designs. He sought to streamline the construction process and make the homes more affordable. Pre-cast concrete blocks, radiant heating systems, and efficient insulation were some of the elements incorporated to achieve these goals. Wright’s house designs featured open floor plans, long horizontal lines, and focus on accommodating the families routine. Wright broke away from the excessive ornamentation and inefficient use of space that is used in service of traditional style in classical architecture.

Historically classical architects like, Leon Krier, have been some of Wright’s biggest detractors. However, I would argue that Wright has more in common with classical architecture than the modernists. Wright himself called the European modern trend an “evil crusade,” and a manifestation of “totalitarianism.” While classism was trying to hold on to historic traditions from Greece and Rome and modernism sought to over throw them; I think Wright was aspiring to make contact with something more ancient. Wright’s philosophy of “organic architecture” was a synthesis of classicism and modernism. He believed that architecture should be rooted in the principles of nature and the cultural and innate structures of the human psyche.

Many of these attempts to access more primal forms than the elements of classical western architecture allowed for resulted in organic shapes, large open spaces, and lines that suggested movement. Wright did not feel that the rigid symmetry and decorative elements of the classicists created the ideal space for humans. He was greatly influenced by ancient Japanese culture and philosophy. He was especially interested in the Zen ideas of wabi-sabi (the acceptance of imperfection and transience) and ma (the notion of space and emptiness). He wanted to create spaces that evoked an instinctual sense of calm, contemplation, and unity with nature. He was greatly influenced by the scholarship of Ernest Fenollosa on Japanese design and history.

Wright was critical of what he saw as a rigid adherence to historical styles and theoretical frameworks within the academic establishment. Wright’s architectural philosophy was deeply rooted in his belief in the potential of architecture to improve the lives of individuals and communities. He believed in designing buildings that were in harmony with nature, functional, and affordable for the middle class. His emphasis on the integration of architecture with its natural surroundings and his innovative use of materials and construction techniques set him apart from the academic mainstream.

Symbolism in Wright’s Process:

One of my favorite parts of Wright’s designs are the artistic motifs and patterns that ripple across the structure. Sometimes brash and bold, sometimes tiny and intricate, they communicate the character and purpose of the space. Wright made hundreds of these designs and often left their final implementation up to his draftsman and tradesman in the final construction. He laid out an intuitive design they could follow without a detailed plan. Some of these patterns have meanings and symbolism documented in plans while others remain a secret that only Wright would know. They are like modern day runes or hieroglyphics across temple walls.

One prominent symbol found throughout Wright’s architectural repertoire is the triangle. Wright often utilized triangular shapes in his designs, whether in the floor plans, rooflines, or windows. The triangle symbolized unity and balance, reflecting Wright’s belief in the harmony between nature, humanity, and architecture. By incorporating triangles into his designs, Wright sought to create a sense of equilibrium and integration between the built environment and its surroundings.

Another symbol frequently found in Wright’s work is the circle or the spiral. Wright was captivated by the organic curves and flow of natural forms, and he often incorporated circular motifs and spiraling patterns in his designs. The circle represented continuity, infinite possibilities, and the cyclical nature of life. It was a symbol of wholeness and completeness, reflecting Wright’s philosophy of architecture as a holistic experience that engages all the senses and connects individuals to their environment.

Nature itself held deep symbolic meaning for Wright. He believed that architecture should be in harmony with nature rather than dominating it. Wright often integrated natural elements, such as water features, plants, and natural light, into his designs. By bringing nature indoors, he created a sense of tranquility, renewal, and spiritual connection. This integration of nature symbolized a respect for the environment and a desire to establish a harmonious relationship between human-made structures and the natural world.

Wright’s designs also incorporated cultural symbolism. He drew inspiration from various cultures, including the Japanese concept of “ma” or spatial void, as well as Native American architecture and design principles. Wright believed that architecture should reflect the cultural context in which it is built and resonate with the identity of its inhabitants. By incorporating cultural symbolism, he aimed to create a sense of place and belonging, honoring the heritage and traditions of the communities he served.

Why Frank Lloyd Wright’s Process is Hard to replicate:

Wright valued the beauty and craftsmanship of handcrafted elements, and his designs often incorporated them extensively. Whether it was custom furniture, light fixtures, or decorative elements, these handcrafted details added richness and uniqueness to his buildings. Skilled craftsmen with expertise in woodworking, metalwork, and other trades were indispensable in creating these bespoke elements that brought Wright’s designs to life.

Wright also believed in a collaborative approach to design, involving craftsmen in the creative process. He encouraged craftsmen to contribute their expertise, ideas, and problem-solving skills, allowing them to innovate and find solutions that aligned with his overall vision. This approach fostered a sense of ownership and pride among the craftsmen, resulting in a high level of dedication and commitment to their work.

Sadly one of the biggest reasons that we failed to remember Wright’s lessons is economic. The arts and crafts movement in architecture relied on skilled artisans to take initiative in certain elements of the designs. It required craftsmen to use their intuition to create new techniques and exercise autonomy in certain parts of the designs. We have moved to a world where everything is prefabricated and shipped to the site. Buildings look the same and architects are limited in what they can expect from the people who construct their designs.

Modern architects now often draw crazy shapes in auto-cad for others to build without even visiting or contemplating the setting for their building. The designer is the expert and does not collaborate with the people who build or work in what they draw. There have been some developments that pushed back on this like the design-build movement, but the industry largely continues to move toward less skilled labor and more inhuman design.

Learning the Wright lessons:

Intuition is at its root the ability to see very complex patterns within something. The best musicians do that sonicly while the best therapists do this through analysis of posture, emotion, family structure and identity. Wright’s architecture was a semi unconscious tuning into the patterns of the natural world, human life and our artistic and spiritual aspirations. When you visit Wright’s spaces you can still hear him listening to patterns that we have forgotten how to hear.

Wrights’ houses often wrap around the family areas in a kind of hug. Unlike Victorian buildings that communicate power and class towards the street, Wright’s buildings shelter the family from the street opening towards the backyard like a shell. In Wright’s homes the focus of the house is on the hearth, family room, and central garden. The street facing walls are striped of detail. His houses often have a minimalist rock or brick exteriors facing the street. They often include water or rock motes and usually small slits windows. They are a re-imagining of the European castle as the center of civilization in an American setting and on a smaller scale. These buildings do not center society around a king or social hierarchy but around the family. The message being that the family is what is valuable, not their social standing.

If there is anything in Wright’s biography that occurred early enough to provide a psychological explanation for the madness of his personal life it would be the contentious divorce of his parents. It is possible that that early loss of a spiritual, emotional, and familial center in his life informed his career trajectory of re-centering the profession of architecture around the idea of nurturing, maternal, and community building spaces.

Good design is a kind of simulacrum. It is a copy of something unconscious and deep within us that does not come from nature but comes from the reflection of nature within ourselves. Our inability to deal with the outer realities of nature or the inner realities of the way we internalize it inform the way we project that into our art. Often our artistic center comes from an early childhood pain. This shadow projection becomes where we are excellent professionally but fail inter-personally. It becomes where we excel with unconscious intuition, but fail to actualize our intuition consciously into our personal lives.

We repeat and recreate our trauma until we face it. I wish I could say that most artists face their trauma but unfortunately most people choose not to go into the scary places. Hell, I wish I could say most therapists face it but we don’t. Timeless art and architecture is inseparable from psychology because it requires us to set our individual ego aside and make contact with something deep inside our collective humanity. My fascination with Wright comes from his process and philosophy for doing this. Not all his work is perfect but his conception of the role architecture plays in our lives was profound.

By infusing his structures with meaningful patterns and symbols taken from nature and human culture, Wright transcended the boundaries of mere functionality. He created spaces that stir emotion and connect deeply with the human spirit. He saw architecture as the intersection of the human, natural and metaphysical world. His buildings were designed more like altars to hold the interplay of these sacred forces. Architecture does shape our lives and enrich our experiences. Whether we notice it or not, architecture helps or harms us.

The contemporary buildings we inhabit now still talk to us but what they say is problematic. They tell us that we are disposable cogs in a set of business transaction and that the most temporary and disposable structures are all we deserve. We send our children into windowless cinder block buildings with linoleum and concrete floors encircled by chain link. Most American schools are built like prisons. We send children there to learn, but learn what I wonder. Leon Krier told me that the Jungian analyst James Hollis told him that European offices are designed so that the eye moves upwards in an aspirational way towards heaven. He said that American offices are designed with harsh fluorescent lighting and cheap drop ceilings so the eyes move to stare down into hell.

“Truth of feature is related to truth of being”

– Frank Lloyd Wright

Digital Tours of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Buildings

References:

- Wright, F. L. (1954). The Natural House. Horizon Press.

- Pfeiffer, B. B. (Ed.). (1987). Frank Lloyd Wright: Collected Writings, Volume 1: 1894-1930. Rizzoli.

- Pfeiffer, B. B. (Ed.). (1992). Frank Lloyd Wright: Collected Writings, Volume 2: 1930-1932. Rizzoli.

- Pfeiffer, B. B. (Ed.). (1993). Frank Lloyd Wright: Collected Writings, Volume 3: 1931-1939. Rizzoli.

- Pfeiffer, B. B. (Ed.). (1994). Frank Lloyd Wright: Collected Writings, Volume 4: 1939-1949. Rizzoli.

- Pfeiffer, B. B. (Ed.). (1995). Frank Lloyd Wright: Collected Writings, Volume 5: 1949-1959. Rizzoli.

- Twombly, R. C. (1979). Frank Lloyd Wright: His Life and His Architecture. Wiley.

- Levine, N. (1996). The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright. Princeton University Press.

- McCarter, R. (1997). Frank Lloyd Wright. Phaidon Press.

- Hoffmann, D. (1995). Understanding Frank Lloyd Wright’s Architecture. Dover Publications.

- Lind, C. (1996). Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian Houses. Pomegranate Communications.

- Sergeant, J. (1976). Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian Houses: The Case for Organic Architecture. Whitney Library of Design.

- Tafel, E. (1985). Apprentice to Genius: Years with Frank Lloyd Wright. McGraw-Hill.

- Meehan, P. J. (Ed.). (1992). Truth Against the World: Frank Lloyd Wright Speaks for an Organic Architecture. Wiley.

- Alofsin, A. (Ed.). (1999). Frank Lloyd Wright: Europe and Beyond. University of California Press.

- De Long, D. G. (1998). Frank Lloyd Wright: Designs for an American Landscape, 1922-1932. Harry N. Abrams.

- Secrest, M. (1998). Frank Lloyd Wright: A Biography. University of Chicago Press.

- Smith, K. (1988). Frank Lloyd Wright: A Study in Architectural Content. Prentice Hall.

- Guerrero, P. (2008). Picturing Wright: An Album from Frank Lloyd Wright’s Photographer. Pomegranate Communications.

- Aguar, C. E., & Aguar, B. (2002). Wrightscapes: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Landscape Designs. McGraw-Hill.

- Van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

- Wright, F. L. (1954). The natural house. Horizon Press.

- Pfeiffer, B. B. (1993). Frank Lloyd Wright collected writings. Rizzoli.

- Twombly, R. C. (1979). Frank Lloyd Wright: His life and his architecture. Wiley.

- Secrest, M. (1992). Frank Lloyd Wright: A biography. University of Chicago Press.

- Levine, N. (1996). The architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright. Princeton University Press.

- Lind, C. (1994). Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian houses. Pomegranate Artbooks.

- McCarter, R. (2006). Frank Lloyd Wright. Reaktion Books.

- Alofsin, A. (1993). Frank Lloyd Wright–the lost years, 1910-1922: A study of influence. University of Chicago Press.

- Hitchcock, H. R. (1976). In the nature of materials, 1887-1941: The buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright. Da Capo Press.

- Meehan, P. J. (1987). Truth against the world: Frank Lloyd Wright speaks for an organic architecture. Wiley.

- Kaufmann, E., & Raeburn, B. (1960). Frank Lloyd Wright: Writings and buildings. Horizon Press.

- Wright, F. L. (1932). An autobiography. Longmans, Green.

- Zevi, B. (1950). Towards an organic architecture. Faber & Faber.

- Brooks Pfeiffer, B. (2004). Frank Lloyd Wright, 1867-1959: Building for democracy. Taschen.

Bibliography:

Alofsin, A. (1993). Frank Lloyd Wright–the lost years, 1910-1922: A study of influence. University of Chicago Press.

Brooks Pfeiffer, B. (2004). Frank Lloyd Wright, 1867-1959: Building for democracy. Taschen.

Hitchcock, H. R. (1976). In the nature of materials, 1887-1941: The buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright. Da Capo Press.

Kaufmann, E., & Raeburn, B. (1960). Frank Lloyd Wright: Writings and buildings. Horizon Press.

Levine, N. (1996). The architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright. Princeton University Press.

Lind, C. (1994). Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian houses. Pomegranate Artbooks.

McCarter, R. (2006). Frank Lloyd Wright. Reaktion Books.

Meehan, P. J. (1987). Truth against the world: Frank Lloyd Wright speaks for an organic architecture. Wiley.

Pfeiffer, B. B. (1993). Frank Lloyd Wright collected writings. Rizzoli.

Secrest, M. (1992). Frank Lloyd Wright: A biography. University of Chicago Press.

Twombly, R. C. (1979). Frank Lloyd Wright: His life and his architecture. Wiley.

Van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

Wright, F. L. (1932). An autobiography. Longmans, Green.

Wright, F. L. (1954). The natural house. Horizon Press.

Zevi, B. (1950). Towards an organic architecture. Faber & Faber.

Further Reading:

Alexander, C., Ishikawa, S., & Silverstein, M. (1977). A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction. Oxford University Press.

Bachelard, G. (1994). The Poetics of Space. Beacon Press.

Boesiger, W. (Ed.). (1995). Le Corbusier: Oeuvre complète (8 volumes). Birkhäuser.

Brooks, H. A. (1972). The Prairie School: Frank Lloyd Wright and His Midwest Contemporaries. W. W. Norton & Company.

Frampton, K. (2001). Studies in Tectonic Culture: The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Architecture. MIT Press.

Frascari, M., Hale, J., & Starkey, B. (Eds.). (2007). From Models to Drawings: Imagination and Representation in Architecture. Routledge.

Heidegger, M. (1971). Poetry, Language, Thought. Harper & Row.

Hertzberger, H. (2005). Lessons for Students in Architecture. 010 Publishers.

Hildebrand, G. (1999). Origins of Architectural Pleasure. University of California Press.

Jencks, C. (1985). Towards a Symbolic Architecture: The Thematic House. Rizzoli.

Krier, L. (2009). The Architecture of Community. Island Press.

Norberg-Schulz, C. (1985). The Concept of Dwelling: On the Way to Figurative Architecture. Rizzoli.

Pallasmaa, J. (2012). The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. Wiley.

Pérez-Gómez, A. (1983). Architecture and the Crisis of Modern Science. MIT Press.

Rasmussen, S. E. (1964). Experiencing Architecture. MIT Press.

Rowe, C., & Slutzky, R. (1976). Transparency. Birkhäuser.

Rykwert, J. (1981). On Adam’s House in Paradise: The Idea of the Primitive Hut in Architectural History. MIT Press.

Scully, V. (1960). Frank Lloyd Wright. George Braziller.

Venturi, R. (1966). Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture. The Museum of Modern Art.

Zumthor, P. (2006). Thinking Architecture. Birkhäuser.

0 Comments