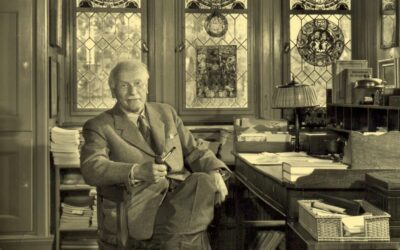

Who was Arne Jacobsen?

Arne Jacobsen (1902-1971) was a seminal figure in Danish modernist architecture and design. Over a prolific career, Jacobsen created a visionary body of work that fused the clean minimalism of the International Style with a distinctively Scandinavian sense of warmth and humanism. His buildings and furnishings exemplified a philosophy of “organic modernism,” embracing the latest technologies and materials while remaining grounded in the tactility of nature and the contours of the human body.

Gesamtkunstwerk: The Total Work of Art

Central to Jacobsen’s approach was the concept of Gesamtkunstwerk, or the “total work of art.” He aspired to create holistic environments where every element—from the building envelope to the doorknobs to the furniture—was carefully conceived to form a unified aesthetic experience. This pursuit of all-encompassing design harmony is evident in masterworks like the SAS Royal Hotel in Copenhagen (1960), where Jacobsen designed not only the iconic curvilinear structure but every interior detail down to the cutlery and ashtrays.

For Jacobsen, this total design ethos was not merely an aesthetic choice but an ethical imperative. He believed that by crafting complete, cohesive environments, the architect could shape human behavior and well-being in profound ways. His spaces were designed to foster a sense of ease, clarity, and social connection, to gently guide users towards more harmonious modes of living and interacting.

Organic Forms and Natural Materials

While working firmly within the functionalist paradigm of modernism, Jacobsen softened its hard geometries with an organic sensibility. His buildings and furnishings often feature gentle curves, tapering lines, and asymmetrical silhouettes inspired by the shapes of nature. The iconic Egg and Swan Chairs (1958), for example, with their enveloping sculptural forms, seem to cradle the body like a protective shell or womb.

This organic language was enhanced by Jacobsen’s sensitive use of materials, particularly his affinity for wood. While he readily adopted the latest industrial technologies, he remained committed to the warmth and tactility of natural surfaces. His furniture often juxtaposes sleek metal frames with richly grained wood veneers, creating a dialog between machined precision and organic variation. Even his most futuristic designs, like the Ant and Series 7 Chairs (1952), retain a sense of crafted authenticity through their molded plywood construction.

Modular Flexibility and Industrial Production

Jacobsen was a pioneer in adapting the principles of mass production to the realm of high-end design. Many of his most iconic furniture pieces, such as the Series 7 Chair, were conceived as modular systems that could be efficiently manufactured and customized for different contexts. By breaking down his designs into standardized components, Jacobsen achieved a remarkable synthesis of industrial rationality and aesthetic refinement.

This modular approach allowed Jacobsen’s designs to be produced at a larger scale and more accessible price point than traditional artisanal furniture. Without compromising his exacting standards of quality and craftsmanship, he helped democratize access to good design, making it available to a broader public. His work anticipated the later success of brands like IKEA in bringing affordable, well-designed furnishings to the mass market.

Humanizing Modernism

Ultimately, Jacobsen’s enduring legacy lies in his ability to humanize the austere language of modernism, to imbue it with a sense of warmth, comfort, and delight. At a time when many of his contemporaries were pursuing a dogmatic, impersonal vision of functionalism, Jacobsen remained deeply attuned to the needs and desires of the human body. His spaces and objects invite tactile engagement and sensory pleasure, from the graceful arc of a chair’s backrest to the satiny sheen of a wood tabletop.

This humanism was rooted in Jacobsen’s abiding faith in the social promise of modernist design. He saw his work not merely as a stylistic exercise but as a means of improving the quality of everyday life, of creating environments that would foster well-being, productivity, and human connection. In an era of increasing standardization and anonymity, Jacobsen’s designs served as a reminder of the enduring value of craftsmanship, individuality, and the human touch.

Half a century after his death, Jacobsen’s vision of organic modernism remains as compelling as ever. In a world of digital fragmentation and environmental crisis, his integrative, nature-inspired approach offers a model of more sustainable, empathetic design. As we grapple with the challenges of the 21st century, Jacobsen’s work invites us to reconnect with the tactile, material world, to find beauty and meaning in the subtle interplay of form and function, technology and craft, the manmade and the organic.

Timeline of Arne Jacobsen’s Designs and Historical Context

1902: Arne Jacobsen is born in Copenhagen, Denmark.

1924: Jacobsen graduates from the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, School of Architecture in Copenhagen.

1925: Bauhaus school opens in Germany, promoting modernist design principles.

1929: Jacobsen wins a silver medal for chair design at the World Exhibition in Barcelona.

1934: Jacobsen designs the Bellavista housing complex in Copenhagen, an early example of functionalist architecture in Denmark.

1937: Jacobsen designs the Ant Chair, his first successful commercial chair design.

1939: World War II begins. Denmark remains neutral initially.

1940: Denmark is occupied by Nazi Germany. Jacobsen flees to Sweden.

1943: Jacobsen designs the Aarhus City Hall in Denmark, a prime example of his functionalist approach.

1947: Jacobsen receives the C.F. Hansen Medal for his contributions to architecture.

1949: Jacobsen begins collaborating with furniture manufacturer Fritz Hansen.

1952: Jacobsen designs the Ant Chair for Fritz Hansen, which becomes an international success.

1955: Jacobsen completes the Rødovre Town Hall in Copenhagen County.

1956: Jacobsen designs the Series 7 Chair, his most commercially successful chair design.

1958: Jacobsen designs the SAS Royal Hotel in Copenhagen, a landmark of midcentury modern architecture and design. He designs every aspect of the hotel, from the building itself to the furnishings, cutlery, and ashtrays.

1959: Jacobsen designs the Egg Chair and Swan Chair for the SAS Royal Hotel.

1960: Jacobsen completes St Catherine’s College, Oxford, his first major international commission.

1965: Jacobsen completes the National Bank of Denmark building in Copenhagen.

1971: Jacobsen dies in Copenhagen at the age of 69.

2002: On Jacobsen’s centenary, the city of Copenhagen hosts a major retrospective exhibition of his work.

2010: The “Arne Jacobsen—Absolutely Modern” exhibition tours internationally, showcasing Jacobsen’s enduring influence on contemporary design.

Bibliography

- Dirckinck-Holmfeld, Kim, and Carsten Thau, eds. Arne Jacobsen. Copenhagen: Danish Architectural Press, 2001.

- Fehrman, Cherie, and Kenneth Fehrman. Interior Design Innovators 1910-1960. San Francisco: Fehrman Books, 2009.

- Geist, Johan. Arne Jacobsen: A Biography. Copenhagen: Danish Architectural Press, 2003.

- Lahti, Louna. Arne Jacobsen: Objects and Furniture Design. New York: Assouline, 2011.

- Pedersen, Michael Asgaard. Arne Jacobsen. Copenhagen: Arkitektens Forlag, 2002.

- Sheridan, Michael. Room 606: The SAS House and the Work of Arne Jacobsen. London: Phaidon, 2003.

- Solaguren-Beascoa, Félix. Arne Jacobsen: Works and Projects. Barcelona: G. Gili, 1991.

- Thau, Carsten, and Kjeld Vindum. Arne Jacobsen. Copenhagen: Danish Architectural Press, 2008.

- Tøjner, Poul Erik, and Kjeld Vindum. Arne Jacobsen: Architect & Designer. Copenhagen: Danish Design Centre, 1996.

- Tøjner, Poul Erik. Arne Jacobsen’s SAS Hotel. Copenhagen: Aschehoug Dansk Forlag, 2007.

Artists and Designers

0 Comments