The Psychology of New Materialism

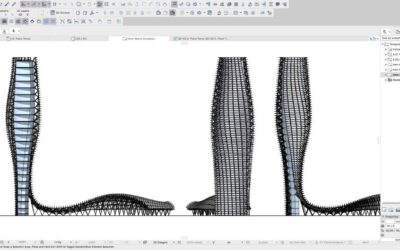

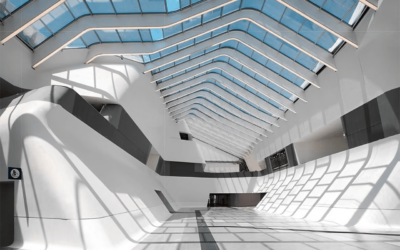

New Materialism in architecture represents a shift in design thinking that emerged in the early 21st century. This approach challenges traditional notions of matter as passive and inert, instead recognizing materials as active agents in the design process. New Materialism in architecture emphasizes the interconnectedness of human and non-human actors, promoting a more ecological and ethically conscious approach to building. In this exploration, we’ll delve into the origins, characteristics, and psychological underpinnings of New Materialism in architecture.

Historical Context and Key Characteristics

New Materialism in architecture developed alongside broader philosophical movements questioning human-centric worldviews. It draws inspiration from various fields, including philosophy, ecology, and material science.

Key features of New Materialist architecture include:

Emphasis on material properties and behaviors in design Integration of living materials and bio-based technologies Focus on the life cycle and ecological impact of materials Exploration of material agency in form-finding processes Consideration of non-human stakeholders in design decisions Blurring of boundaries between natural and built environments Experimentation with novel materials and fabrication techniques

Dialectical Materialist Perspective

From a dialectical materialist viewpoint, New Materialism in architecture represents a synthesis of ecological consciousness and technological innovation. It emerged from the contradiction between anthropocentric design practices and the recognition of complex material ecologies. The movement embodies the tension between human creative intent and the agency of materials and environmental systems.

Jungian Depth Psychology Analysis

Through the lens of Carl Jung’s analytical psychology, as explained in this guide to understanding Carl Jung’s method, New Materialism in architecture can be interpreted as an expression of several archetypes.

The movement’s recognition of material agency evokes the Nature archetype, representing a deep connection with the physical world. The exploration of novel materials and processes might be seen as an expression of the Explorer archetype, embodying curiosity and discovery.

The attempt to create more symbiotic relationships between buildings and their environments could be interpreted as a manifestation of the Self archetype, representing the drive towards wholeness and integration. The style’s balance between human design intent and material behaviors might be seen as a reconciliation of the Animus (associated with active shaping) and Anima (associated with receptivity) archetypes.

Ego Perspective: Assertions and Insecurities

New Materialism in architecture serves to assert a more humble and ecologically conscious approach to design. Its approach projects an image of ethical responsibility and environmental awareness. The style’s emphasis on material exploration asserts a commitment to innovation and sustainability in architectural practice.

However, the movement also reveals certain cultural insecurities. Its focus on non-human agency might be seen as a reaction to anxieties about human exceptionalism and its environmental consequences. The emphasis on ecological thinking could reflect insecurities about the long-term viability of traditional architectural practices in the face of environmental challenges.

Lasting Influence and Modern Context

New Materialism has significantly influenced contemporary architectural discourse and practice, particularly in avant-garde and experimental design. Its principles have encouraged architects to consider materials not just for their aesthetic or structural properties, but as active participants in the life of a building.

In the modern context, New Materialist approaches are informing the development of “living” architecture that incorporates biological processes and responds dynamically to environmental conditions. The movement has also influenced the growth of biomimicry in architecture, where designers look to nature for sustainable solutions.

New Materialism has contributed to advancements in material science and fabrication techniques in architecture, pushing for more sustainable and locally sourced materials. It has also influenced architectural education, promoting a more holistic understanding of materials and their ecological contexts.

As environmental concerns continue to grow, the principles of New Materialism are likely to become increasingly relevant in mainstream architectural practice. The movement is challenging architects to think beyond traditional notions of form and function, encouraging a more nuanced and ecologically integrated approach to design.

The lasting legacy of New Materialism in architecture may be its reconceptualization of the relationship between buildings, materials, and the environment, promoting a more symbiotic and sustainable approach to the built world.

Bibliography: The City Beautiful Movement

Bohl, C. C. (2009). “City Beautiful Movement.” In Encyclopedia of Urban Studies, edited by Ray Hutchison, 155-158. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Bluestone, D. M. (1988). “Detroit’s City Beautiful and the Problem of Commerce.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 47(3), 245-262.

Brown, J. K. (2006). Health and Medicine on Display: International Expositions in the United States, 1876-1904. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Burnham, D. H., & Bennett, E. H. (1909). Plan of Chicago. Chicago: The Commercial Club.

Hall, P. (2002). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design in the Twentieth Century. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Hines, T. S. (1974). Burnham of Chicago: Architect and Planner. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Howard, E. (1902). Garden Cities of To-morrow. London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co.

Klaus, S. L. (2002). A Modern Arcadia: Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. and the Plan for Forest Hills Gardens. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Krueckeberg, D. A. (ed.) (1983). Introduction to Planning History in the United States. New Brunswick, NJ: Center for Urban Policy Research.

Peterson, J. A. (2003). The Birth of City Planning in the United States, 1840-1917. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Robinson, C. M. (1901). The Improvement of Towns and Cities: Or, The Practical Basis of Civic Aesthetics. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Scott, M. (1969). American City Planning Since 1890. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Sidorick, D. (2015). “The ‘Girl Strike’ at Heinz’s Pickle Works and the Limits of the ‘New Unionism’ in Pittsburgh.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, 82(2), 158-185.

Wilson, W. H. (1989). The City Beautiful Movement. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Zukowsky, J. (ed.) (1987). Chicago Architecture, 1872-1922: Birth of a Metropolis. Munich: Prestel-Verlag.

0 Comments