The Psychology of Gothic Revival

What is Gothic Revival?

Gothic Revival architecture, flourishing from the late 18th to the early 20th centuries, represents a romantic reimagining of medieval Gothic style. This movement, characterized by pointed arches, steep gables, and ornate decorations, emerged as a reaction against the formal classical styles that preceded it. In this exploration, we’ll examine the origins, characteristics, and psychological underpinnings of Gothic Revival architecture.

Historical Context and Key Characteristics

Gothic Revival gained popularity during the Industrial Revolution, partly as a nostalgic response to rapid modernization. Key characteristics include:

- Pointed arches

- Steep, gabled roofs

- Castle-like towers and spires

- Ornate decorations and tracery

- Clustered columns

- Large windows with decorative glazing

- Emphasis on vertical lines

Cultural Context

The rise of Gothic Revival architecture coincided with a period of significant cultural and social change. The Industrial Revolution was transforming the way people lived and worked, leading to a sense of nostalgia for a perceived simpler, more spiritual past. The Romantic movement in literature and art also contributed to a renewed interest in medieval culture and aesthetics. Gothic Revival architecture reflected these cultural shifts, offering a means of connecting with a romanticized past and expressing spiritual and emotional depth in an increasingly secularized world.

Technological Advances

While Gothic Revival architecture often sought to emulate the craftsmanship of the Middle Ages, it also benefited from technological advances of the Industrial Revolution. The development of cast iron and other mass-produced building components allowed for the creation of more elaborate and ornate structures. Improvements in engineering and building techniques also made it possible to construct taller, more complex buildings with larger windows and more intricate detailing.

Political Landscape

The political landscape of the 18th and 19th centuries was marked by significant upheaval and change, including the French Revolution, the rise of nationalism, and the expansion of the British Empire. Gothic Revival architecture often served as a means of asserting power and authority, particularly in institutional buildings such as churches, universities, and government offices. The style’s association with the medieval past also lent it a sense of cultural legitimacy and continuity, which was particularly appealing in an age of rapid social and political change.

Key Innovators

Several influential architects and designers were at the forefront of the Gothic Revival movement, including:

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin: British architect and designer who was a leading proponent of the Gothic Revival style, known for his work on the Houses of Parliament in London.

John Ruskin: British art critic and social thinker whose writings on the moral and spiritual significance of Gothic architecture were highly influential.

Sir George Gilbert Scott: British architect who designed numerous churches, public buildings, and country houses in the Gothic Revival style.

Richard Upjohn: American architect known for his Gothic Revival churches, including Trinity Church in New York City.

Related Architectural Styles

Gothic Revival architecture is closely related to and often overlaps with other architectural styles of the 18th and 19th centuries, including:

Romantic Architecture: A style that emphasized emotion, nature, and the picturesque, often drawing inspiration from medieval and exotic sources.

Victorian Architecture: A broad term encompassing various styles popular during the reign of Queen Victoria, often characterized by eclecticism and historicism.

Collegiate Gothic: A subtype of Gothic Revival architecture that was particularly popular for educational buildings in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Dialectical Materialist Perspective

From a dialectical materialist viewpoint, Gothic Revival represents a synthesis of:

- Industrialization’s capabilities (mass-produced decorative elements)

- Romantic idealization of pre-industrial craftsmanship

- Class dynamics (association with aristocratic and ecclesiastical power)

- Technological advancements allowing for taller, more elaborate structures

The style emerged from the contradiction between the efficiency and standardization of industrial production and the desire for unique, handcrafted objects. It embodied the tension between the pursuit of progress and the longing for a romanticized past.

Jungian Depth Psychology Analysis

Through a Jungian lens, Gothic Revival embodies:

- The Shadow: Representing the “dark,” emotional aspects repressed by Enlightenment rationality

- The Anima/Animus: The style’s romantic nature reflecting a collective yearning for spiritual and emotional depth

- The Self: Aspiration towards transcendence symbolized by soaring spires

The emphasis on emotion, spirituality, and the supernatural in Gothic Revival architecture can be seen as an expression of the Shadow, the unconscious aspects of the psyche that were often repressed or denied in the Age of Reason. The romantic and imaginative qualities of the style reflect the Anima/Animus archetypes, representing the integration of feminine and masculine qualities. The soaring verticality of Gothic Revival buildings can be interpreted as a manifestation of the Self archetype, representing the human quest for self-realization and transcendence.

Ego Perspective: Assertions and Insecurities

Gothic Revival served to:

- Assert cultural sophistication and historical continuity

- Project power and authority (particularly in institutional buildings)

- Express spiritual and emotional depth in a rapidly secularizing world

It also revealed insecurities about:

- Loss of craftsmanship and beauty in the industrial age

- Spiritual emptiness in an increasingly materialistic society

- Rapid social changes threatening established hierarchies

The emphasis on craftsmanship, beauty, and spirituality in Gothic Revival architecture can be seen as an assertion of cultural sophistication and continuity, as well as a projection of power and authority. However, the style also revealed underlying insecurities about the impact of industrialization and secularization on human society and culture, as well as anxieties about the erosion of traditional social hierarchies.

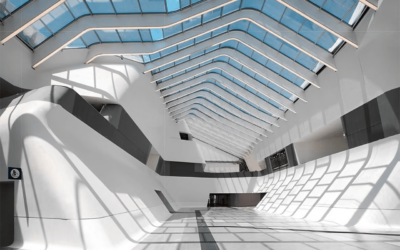

Lasting Influence, Criticisms, and Modern Context

Gothic Revival continues to influence architecture, particularly in religious and educational buildings. The style has been praised for its ability to evoke a sense of mystery, spirituality, and historical depth, as well as for its masterful use of ornament and craftsmanship. However, it has also been criticized for its sometimes excessive or inauthentic use of medieval motifs, as well as for its association with conservative or reactionary social and political views.

In the modern context, Gothic Revival architecture remains a popular choice for institutions seeking to convey a sense of tradition, authority, and cultural legitimacy. The style’s emphasis on emotion, imagination, and spirituality continues to resonate with many people in an increasingly fast-paced and secularized world. At the same time, the social and political implications of the style continue to be debated, as architects and historians grapple with issues of authenticity, appropriation, and the role of the past in shaping the present.

Bibliography and Further Reading

- Aldrich, M. (2005). Gothic Revival. Phaidon Press.

- Brooks, C. (1999). The Gothic Revival. Phaidon Press.

- Clark, K. (1962). The Gothic Revival: An Essay in the History of Taste. John Murray.

- Eastlake, C. L. (1872). A History of the Gothic Revival. Longmans, Green, and Co.

- Germann, G. (1972). Gothic Revival in Europe and Britain: Sources, Influences and Ideas. Lund Humphries.

- Lewis, M. J. (2002). The Gothic Revival. Thames & Hudson.

- McCarthy, M. (1987). The Origins of the Gothic Revival. Yale University Press.

- Pugin, A. W. N. (1841). The True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture. John Weale.

0 Comments