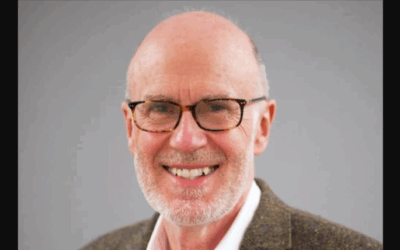

Who is Dr. Graham Harvey?

Breaking from Early Theorists

British scholar Graham Harvey, a prominent voice in religious studies since the 1990s, has played a key role in updating the anthropology of religion for the 21st century. His work breaks from the mold of early luminaries like E.B. Tylor, James Frazer, and Mircea Eliade, who tended to view indigenous and pagan religions through a lens of “primitive” superstition and irrationality.

Tylor and Frazer, writing in the late 19th century, largely saw animistic and polytheistic beliefs as early evolutionary stages to be surpassed by civilized monotheism and scientific rationality. Eliade, active in the mid-20th century, romanticized traditional cultures as exemplars of the sacred in contrast to modern secular life, but still positioned them as objects of study for Western experts.

Harvey, in contrast, insists on engaging indigenous and pagan communities as equals, with sophisticated worldviews and values relevant to contemporary global challenges. He rejects narratives of progress in which indigenous wisdom must give way to Western modernity.

The “New Animism”

Central to Harvey’s approach is his concept of the “new animism.” While early anthropologists used “animism” to label a childlike belief in spirits in all natural phenomena, Harvey reclaims the term to describe complex relationships between human and non-human persons.

Drawing on his fieldwork with indigenous communities from North America to Asia, Harvey shows how people interact with animals, plants, elements and land-forms not as soulless resources but as sentient beings deserving of respect. Such “other-than-human persons,” in his view, are active participants in social and ecological networks.

This “new animism” dissolves modern dualisms of human/nature, subject/object, and material/spiritual. It points to more relational, reciprocal ways of inhabiting the world. For Harvey, taking animism seriously is key to confronting environmental crises and healing human-earth connections.

Paganism and Pluralism

Harvey also stands out in his nuanced engagement with contemporary Pagan and New Age movements, which blend ancient polytheistic beliefs with new spiritual experiments. Rather than dismissing them as fringe or regressive, he explores their potential to revitalize nature-based values and expand religious diversity.

At the same time, Harvey is careful not to equate neo-pagan innovations with the ongoing traditions of indigenous peoples still struggling for cultural survival. He emphasizes the distinct identities and contexts of different groups while tracing resonances between them.

Overall, Harvey exemplifies an open, pluralistic approach to the multiplicity of spiritual paths, both old and new, around the world. He challenges anthropologists to overcome ethnocentric biases, engage respectfully with different worldviews, and allow themselves to be transformed in the process.

Harvey’s Work in Relation to Jungian Theory

Points of Commonality

The Power of Myth and Symbol

There are significant resonances between Harvey’s approach to indigenous and pagan religions and the psychological theories of Carl Jung. Both thinkers emphasize the central role of myth, symbol, and ritual in shaping human experience and identity.

For Jung, mythic archetypes emanating from the collective unconscious structure individual psyches and provide a blueprint for the journey toward wholeness. Ancient symbols like the mandala or the world tree, in his view, spontaneously appear in dreams and visions across cultures, pointing to universal patterns.

Harvey, too, stresses how sacred stories and ceremonial practices serve to orient communities in the cosmos and provide meaning and coherence. Myths of trickster heroes or mother goddesses, for example, encode deep truths and ethical values. Rituals of initiation or pilgrimage enact powerful transformations.

Engaging Non-Western Wisdom

Jung was a pioneer in crossing cultural boundaries and integrating non-Western spiritual concepts into modern psychology. He drew on traditions ranging from Taoism and Hinduism to Gnosticism and alchemy, seeing them as repositories of timeless insight into the human condition.

Harvey shares this openness to learning from diverse global wisdom traditions. His work centers the voices and experiences of indigenous peoples from the Americas to Africa to Australia. He invites readers to step outside of Western paradigms and encounter radically different ways of being.

For both Jung and Harvey, non-Western cultures offer vital resources for individual and collective healing in an era of fragmentation and ecological crisis. Indigenous and pagan ways of sacred relating to the earth, in particular, point toward more balanced, reciprocal modes of living.

Numinous Experience

The direct experience of the sacred—what Rudolf Otto called the “numinous”—plays a key role in both Harvey’s anthropology and Jungian psychology. For Jung, numinous encounters with the transcendent, often mediated through dreams or active imagination, are essential catalysts for individuation and self-realization.

Similarly, for the communities Harvey studies, shamanic journeys, encounters with spirits, and divine possession states are central means of knowing and connecting with the sacred. Rituals induce altered states of consciousness in which ancestors or nature beings become vividly present.

Both thinkers take seriously the reality and power of such numinous experiences, seeing them not as mere superstition or delusion but as genuine engagements with a more-than-human world. The sacred, in this sense, is not just an abstract concept but a lived relationship.

Critiques and Divergences

The Perils of Universalism

While Jung and Harvey both value non-Western traditions, Harvey is warier of universalizing or decontextualizing them. Jung sought to discern universal archetypes and patterns across cultures, fitting diverse myths and symbols into his own overarching theory of the psyche.

Harvey, in contrast, emphasizes the radical particularity of each tradition, rooted in specific landscapes, histories, and social contexts. He resists collapsing them into a single spiritual monomyth.

For example, while Jung saw the medicine wheel of the Plains Indians as a version of the generic mandala archetype, Harvey insists on grappling with its unique meanings for the Lakota or Cheyenne nations. The wheel cannot be separated from its embeddedness in kinship systems, migration routes, and centuries of colonial violence.

Beyond the Psyche

Harvey’s work also implicitly challenges the Jungian tendency to psychologize religion—to view myths and rituals primarily as symbolic expressions of mental states and individuation processes. For the peoples Harvey studies, gods and spirits are not just inner figures but real ontological beings with whom humans interact.

In indigenous and pagan traditions, the material and the spiritual are not sharply divided but interpenetrate each other. The sacred is immanent in the physical world, not just the depths of the psyche.

Yuwipi ceremonies of the Lakota call spirits into the ritual space to heal illnesses. Balinese temple festivals invite deities to inhabit wooden and stone statues. The Inari fox shrines of Japan provide homes for a rice deity to ensure agricultural fertility. Such practices cannot be reduced to intrapsychic events.

Politics and Power

Perhaps the most crucial difference between Harvey and Jung is the former’s greater attention to the political and economic dimensions of religion. Whereas Jung tended to focus on individual spiritual development, Harvey situates indigenous and pagan traditions within histories of colonialism, cultural genocide, and capitalist exploitation.

For Harvey, the revival of traditional nature-venerating practices cannot be separated from indigenous peoples’ struggles for sovereignty, land rights, and environmental justice. Pagan re-inventions of pre-Christian European paths are bound up with resistance to patriarchal monotheisms and industrial modernity.

A purely psychological approach, Harvey suggests, risks obscuring the real-world power dynamics and social conflicts in which religions are always embedded. Myths and rituals are not just timeless archetypes but sites of historical contestation and change.

Participatory Ethics

Finally, Harvey advocates for a more participatory and ethically-engaged model of anthropology than was common in Jung’s time. Rather than positioning themselves as detached experts, he calls on researchers to fully involve themselves in the lifeworlds of those they study, even to the point of “going native.”

This means not just objectively documenting rituals but taking part in them, apprenticing to shamans and priests, and allowing oneself to be existentially transformed. It means being accountable to indigenous and pagan communities, supporting their self-determination, and reciprocating the gifts of knowledge received.

Jung, in contrast, largely remained the doctor-analyst, drawing on non-Western traditions to expand his own theories but not fundamentally rethinking his authority. His universalism, as critics note, could veer into a kind of appropriation or decontextualization of indigenous wisdom.

Harvey thus calls for a humbler, more relational approach in which anthropologists see themselves as partners in dialogue rather than masters of understanding. He invites us to be open to radically different ways of being and knowing, even when they unsettle our deepest assumptions.

In conclusion, while Harvey shares with Jung a deep appreciation for the power of myth, symbol, and spiritual experience across cultures, he also moves beyond Jungian theory in crucial ways. His focus on the historical and political specificity of traditions, his challenge to the spiritual/material divide, and his call for participatory ethics all mark important advances.

At the same time, Harvey’s vision of a “new animism” in which all beings are respected as sacred persons resonates with Jung’s sense of a world re-enchanted by the depths of the psyche. Both thinkers, in their own ways, summon us to a more integral, reciprocal, and wonder-filled engagement with the more-than-human universe.

As the West grapples with ecological and existential crises, Harvey and Jung both point us back to the wisdom of the Earth and the collective realities that flow beneath the illusions of modern individualism. The marriage of mythic imagination and material commitment modeled by Harvey’s work will be essential in the decades to come.

Bibliography

Alles, G. D. (2005). Religion [Further Considerations]. In L. Jones (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Religion (2nd ed., Vol. 11, pp. 7701-7706). Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA.

Bowie, F. (2013). Building Bridges, Dissolving Boundaries: Toward a Methodology for the Ethnographic Study of the Afterlife, Mediumship, and Spiritual Beings. Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 81(3), 698-733.

Eliade, M. (1959). The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

Frazer, J. G. (1890). The Golden Bough: A Study in Comparative Religion. London: Macmillan and Co.

Harvey, G. (2005). Animism: Respecting the Living World. London: Hurst & Co.

Harvey, G. (2013). Food, Sex and Strangers: Understanding Religion as Everyday Life. Durham: Acumen.

Harvey, G. (Ed.). (2013). The Handbook of Contemporary Animism. Durham: Acumen.

Harvey, G. (2017). Animism: Respecting the Living World (2nd ed.). London: Hurst & Co.

Jung, C. G. (1968). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious (2nd ed.). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1969). Psychology and Religion: West and East. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1989). Memories, Dreams, Reflections. New York: Vintage Books.

Laughlin, C. D., & Throop, C. J. (2003). Experience, Culture, and Reality: The Significance of Fisher Information for Understanding the Relationship Between Alternative States of Consciousness and the Structures of Reality. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 22(1), 7-26.

Morrison, K. M. (2013). Animism and a proposal for a post-Cartesian anthropology. In G. Harvey (Ed.), The Handbook of Contemporary Animism (pp. 38-52). Durham: Acumen.

Otto, R. (1923). The Idea of the Holy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Saler, B. (1993). Conceptualizing Religion: Immanent Anthropologists, Transcendent Natives, and Unbounded Categories. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Smith, J. Z. (1998). Religion, Religions, Religious. In M. C. Taylor (Ed.), Critical Terms for Religious Studies (pp. 269-284). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Stringer, M. D. (2008). Contemporary Western Ethnography and the Definition of Religion. London: Continuum.

Tylor, E. B. (1871). Primitive Culture: Researches into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Art, and Custom. London: John Murray.

Viveiros de Castro, E. (1998). Cosmological Deixis and Amerindian Perspectivism. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 4(3), 469-488.

von Franz, M.-L. (1995). Creation Myths. Boston: Shambhala.

Wallis, R. J. (2003). Shamans/Neo-Shamans: Ecstasy, Alternative Archaeologies and Contemporary Pagans. London: Routledge.

Whitehead, A. N. (1978). Process and Reality: An Essay in Cosmology. New York: Free Press.

York, M. (2003). Pagan Theology: Paganism as a World Religion. New York: New York University Press.

0 Comments