The Mad Scientist Who Made Flipper Look Like a Documentary

The Mad Scientist Who Made Flipper Look Like a Documentary

Picture this: It’s 1965, and while most scientists are content with their lab coats and microscopes, one maverick researcher is floating in a pitch-black tank filled with body-temperature salt water, high on ketamine, trying to establish interspecies communication with dolphins. No, this isn’t the plot of a B-movie (though it inspired several). This was Tuesday for Dr. John C. Lilly, the neuroscientist who took “thinking outside the box” to mean “thinking inside a sensory deprivation tank while on horse tranquilizers.”

From Respectable Neuroscientist to Cetacean Whisperer: The Journey Begins

John Cunningham Lilly started his career as a perfectly respectable medical doctor and neuroscientist. Born in 1915, he earned his medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania and seemed destined for a conventional scientific career. But somewhere between inventing the isolation tank in 1954 and deciding that dolphins were just aquatic philosophers waiting for the right conversation partner, things took a decidedly unconventional turn.

The 1960s and ’70s were a special time in American consciousness research. The counterculture movement had collided head-on with Cold War paranoia, creating a perfect storm where the CIA was literally funding research into psychic powers, and respected universities were hosting conferences on altered states of consciousness. It was an era when Carl Jung’s ideas about the collective unconscious weren’t just academic theories—they were roadmaps for exploration, and everyone from Timothy Leary to the folks at Langley wanted in on the action.

The Isolation Tank: Lilly’s Portal to Inner Space

Before the dolphins entered the picture, Lilly invented what he called the “isolation tank” (now more soothingly marketed as “float tanks” at your local wellness center). The concept was simple: remove all external stimuli and see what happens to human consciousness. The execution was decidedly more complex, involving a lightproof, soundproof tank filled with skin-temperature water saturated with Epsom salts.

Lilly’s initial experiments were relatively tame—he was interested in what would happen to the brain when deprived of sensory input. Would it shut down? Go haywire? Create its own reality? (Spoiler alert: it’s mostly option three.) But this was the ’70s, and simply floating in darkness wasn’t nearly groovy enough. Enter the psychedelics.

Ketamine: The Horse Tranquilizer That Became a Spiritual GPS

If Lilly’s isolation tank was a rocket ship, ketamine was the fuel that sent him to the outer reaches of consciousness. Originally developed as an anesthetic, ketamine had the peculiar property of dissociating the mind from the body while maintaining consciousness. For Lilly, this wasn’t a bug—it was a feature.

He began using ketamine in conjunction with his isolation tank sessions, creating what he believed was a direct hotline to higher dimensions of consciousness. During these sessions, Lilly reported encounters with what he called “ECCO” (Earth Coincidence Control Office), a sort of cosmic bureaucracy that he believed was orchestrating coincidences in human life. Yes, you read that correctly—the man thought he was filing reports with interdimensional middle management.

Project Dolphin: When Marine Biology Meets Mysticism

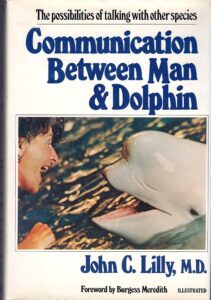

But Lilly’s most famous (or infamous) work involved dolphins. Convinced that these marine mammals possessed intelligence comparable to humans, he established the Communication Research Institute in the Virgin Islands. The goal? Teach dolphins to speak English. The method? Well, that’s where things get weird.

The most notorious experiment involved a young research assistant named Margaret Howe Lovatt, who lived with a dolphin named Peter in a partially flooded house for several months. The idea was total immersion—if Peter was constantly exposed to human speech, surely he’d pick it up like a aquatic toddler. What actually happened was that Peter developed what can only be described as romantic feelings for Margaret, leading to some of the most awkward scientific documentation ever written.

Meanwhile, Lilly was experimenting with giving LSD to dolphins (because of course he was), believing it might enhance their communication abilities. The ethics committees of today would have a collective aneurysm, but this was the Wild West of consciousness research, where the only limit was your imagination and your drug tolerance.

The CIA Connection: Your Tax Dollars at Work

Here’s where the story takes a turn toward the conspiratorial. The CIA, through programs like MK-ULTRA, was deeply interested in consciousness manipulation and enhancement. They saw potential military applications in everything from psychic communication to mind control. Lilly’s work, particularly with isolation tanks and altered states, attracted their attention and funding.

Documents released decades later revealed that the intelligence community was particularly interested in Lilly’s work on interspecies communication. The logic, apparently, was that if we could talk to dolphins, maybe we could also develop new forms of coded communication or even train marine mammals for intelligence operations. (The U.S. Navy’s Marine Mammal Program, which still exists today, suggests this wasn’t entirely far-fetched.)

The Jungian Connection: Diving Deep into the Collective Unconscious

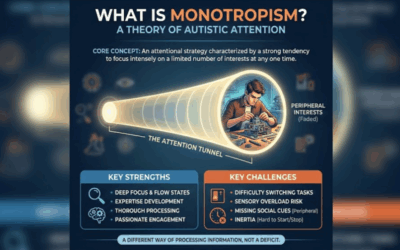

Lilly’s work resonated deeply with the ideas of Carl Jung that were experiencing a renaissance in 1970s California. Jung’s concepts of the collective unconscious, archetypes, and synchronicity seemed to find empirical validation in Lilly’s tank experiences. When you’re floating in darkness, disconnected from your body, encountering what seem to be universal symbols and entities, Jung’s theories suddenly feel less like psychology and more like a user manual for consciousness.

The Human Potential Movement, centered around places like Esalen Institute in Big Sur, embraced Lilly as a kindred spirit. Here was a “real” scientist who was proving what the mystics had been saying all along—that consciousness was far more vast and mysterious than materialist science admitted.

Hollywood’s Love Affair with Lilly

Lilly’s work captured the imagination of Hollywood in ways that would make him either proud or mortified, depending on his ketamine levels that day. The most direct adaptation was “Altered States” (1980), where William Hurt plays a scientist who uses isolation tanks and psychedelics to devolve into a primitive consciousness. The film took Lilly’s concepts and cranked them up to eleven, complete with spectacular visual effects and a plot that made Lilly’s actual experiences seem mundane by comparison.

“Day of the Dolphin” (1973) starring George C. Scott, took Lilly’s dolphin communication research and added a thriller twist—what if dolphins could be trained as assassins? The film’s tagline, “Unwittingly, he trained a dolphin to kill the President of the United States,” suggests Hollywood’s relationship with scientific accuracy was as loose as Lilly’s relationship with consensus reality.

Even the “Ecco the Dolphin” video game series, while not directly credited to Lilly, bears unmistakable influences from his work. A dolphin navigating alien worlds and traveling through time? That’s basically a Tuesday in Lilly’s research notes.

The Scientific Legacy: Kernels of Truth in a Psychedelic Shell

Here’s the thing about Lilly’s work—buried beneath the ketamine visions and dolphin love triangles were some genuinely important insights. His isolation tank research contributed to our understanding of sensory deprivation and its effects on consciousness. Float therapy is now a legitimate wellness practice, backed by research showing benefits for stress reduction, pain management, and creativity enhancement.

His dolphin research, while it didn’t produce English-speaking cetaceans, did contribute to our understanding of marine mammal intelligence. We now know that dolphins have complex social structures, can recognize themselves in mirrors, and communicate in ways we’re still trying to understand. They may not be discussing philosophy, but they’re certainly more than just smart fish.

Even his experimentation with altered states, while ethically questionable and scientifically unrigorous by today’s standards, prefigured current research into psychedelics for treating depression, PTSD, and end-of-life anxiety. The difference is that modern researchers use controlled doses and statistical analysis, not heroic doses and cosmic coincidence offices.

The Dark Side of the Tank

It wasn’t all interdimensional enlightenment and cetacean communication. Lilly’s ketamine use escalated to dangerous levels—at one point, he was injecting himself hourly. He nearly died multiple times, and his later years were marked by increasing disconnection from consensus reality. His story serves as a cautionary tale about the difference between exploring consciousness and losing yourself in it.

His dolphin experiments, viewed through a modern lens, raise serious ethical questions. The conditions at his research facilities were often poor, and several dolphins died under his care. The sexual behavior exhibited by Peter toward Margaret would today be recognized as a welfare concern, not a breakthrough in communication.

What Lilly Got Wrong (Spoiler: A Lot)

Let’s be clear: taking massive doses of ketamine in an isolation tank does not actually allow you to communicate with cosmic entities. ECCO doesn’t exist (probably). Dolphins, while intelligent, are not waiting to engage in philosophical discourse about the nature of reality. And the CIA’s interest in consciousness research produced more ethical violations than operational intelligence assets.

Lilly’s mistake was confusing subjective experience with objective reality. The fact that ketamine can produce profound alterations in consciousness doesn’t mean those experiences represent contact with higher dimensions. The brain is perfectly capable of generating elaborate hallucinations without any help from interdimensional bureaucrats.

What We Can Learn from Lilly’s Wild Ride

Despite its excesses, Lilly’s work reminds us that consciousness remains one of the great mysteries of science. We still don’t fully understand how subjective experience arises from objective neural activity. We’re still discovering the extent of non-human intelligence. And we’re still exploring how altered states might be therapeutically useful.

Lilly’s willingness to use himself as a test subject, while dangerous and inadvisable, came from a genuine desire to understand consciousness from the inside out. In an era of increasing specialization and compartmentalization in science, there’s something refreshing about a researcher who refused to separate the observer from the observed.

The Modern Float Tank: Lilly’s Legacy, Hold the Ketamine

Today, float tanks are a multi-million dollar industry. Stripped of their psychedelic associations, they’re marketed as tools for relaxation, meditation, and creativity enhancement. Users report profound experiences without any chemical assistance—turns out the brain is quite capable of producing interesting states all on its own.

Modern dolphin research has also vindicated some of Lilly’s intuitions about cetacean intelligence, even if his methods were questionable. We now study dolphin communication with hydrophones and computer analysis, not LSD and swimming pools.

A Cautionary Tale of Consciousness

John C. Lilly’s story is ultimately about the human desire to transcend ordinary consciousness and touch something greater. Whether that “something” is God, alien intelligence, or simply unexplored regions of our own minds remains an open question. His willingness to push boundaries—pharmacological, ethical, and professional—produced insights alongside cautionary tales.

In our current era of renewed interest in consciousness research and psychedelic therapy, Lilly serves as both inspiration and warning. Yes, consciousness is vast and mysterious and worthy of exploration. But maybe—just maybe—we can explore it without the hourly ketamine injections and uncomfortable interspecies relationships.

The 1970s were a unique moment when the boundaries between science, spirituality, and speculation were remarkably porous. Figures like Lilly could move between university laboratories, CIA-funded projects, and New Age conferences without missing a beat. That world is gone, replaced by IRB protocols and peer review. But the questions Lilly asked—about consciousness, intelligence, and the nature of mind—remain as relevant and mysterious as ever.

So the next time you see a dolphin at an aquarium or consider trying a float tank at your local spa, spare a thought for John C. Lilly. He may not have found God in a ketamine vision or taught dolphins to speak English, but he certainly made the journey interesting. And in the end, isn’t that what the ’70s were all about?

0 Comments