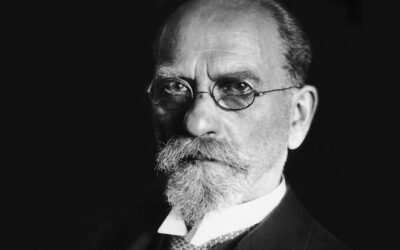

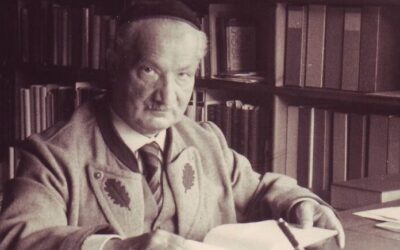

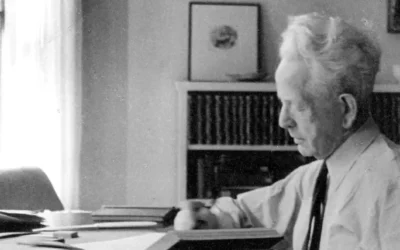

Who is Jürgen Habermas?

Jürgen Habermas (1929-) is one of the most influential philosophers and social theorists of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. As the leading figure of the “second generation” of the Frankfurt School, Habermas has made groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of communicative rationality, discourse ethics, democratic deliberation, and the public sphere. While not primarily a psychologist, Habermas’s ideas have profound implications for depth psychology and contemporary therapeutic practice that are only beginning to be explored.

At the heart of Habermas’s thought is his theory of communicative action, which he developed as a critical response to the instrumentalization of reason in modern societies. Habermas argues that the Enlightenment ideal of rationality has been distorted and narrowed under the pressures of capitalism, bureaucracy, and technological control. In the process, reason has been reduced to a mere tool for achieving strategic ends, divorced from the lifeworld of shared meanings and moral norms.

Against this backdrop, Habermas seeks to recover a more holistic and intersubjective understanding of rationality grounded in communication and dialogue. For Habermas, reason is not a monological faculty of the isolated subject but an inherently social and discursive phenomenon that emerges through the exchange of arguments and the search for mutual understanding. Communicative rationality is thus not instrumental but relational, not strategic but consensual.

This communicative paradigm has profound implications for depth psychology and the theory and practice of psychotherapy. It challenges the traditional notion of the therapist as an expert technician who applies standardized interventions to “fix” the client’s psychopathology. Instead, it suggests that therapy is fundamentally a dialogical and collaborative process in which therapist and client work together to co-create new meanings and narratives.

From a Habermasian perspective, the goal of therapy is not simply symptom reduction or behavioral change but the expansion of the client’s communicative competence and capacity for self-reflection. The therapist’s role is to create a safe and supportive space for authentic dialogue, to help the client articulate their own experiences and perspectives, and to facilitate a process of mutual understanding and consensus-building.

This approach resonates with many humanistic and existential therapies that emphasize the centrality of the therapeutic relationship and the client’s subjectivity. It also aligns with the growing interest in narrative and social constructionist approaches that view identity as a fluid and contextual reality shaped through language and interaction.

At the same time, Habermas’s theory challenges the individualistic bias of much Western psychology and psychotherapy. It reminds us that the self is not a pre-given entity but a social construct that emerges through interaction and dialogue with others. As such, therapy must attend not just to the client’s intrapsychic dynamics but to the broader relational and cultural contexts that shape their experience.

This points to the need for a more politically engaged and socially conscious therapeutic practice that links individual healing to collective transformation. Habermas’s concept of the public sphere as a space for critical deliberation and democratic will-formation suggests that therapy can play a vital role in fostering citizen empowerment and social change.

By helping clients develop their communicative competence and capacity for critical reflection, therapy can contribute to the revitalization of civil society and the democratization of social institutions. It can also serve as a catalyst for new forms of solidarity and collective action in response to the crises of our time.

Habermas’s discourse ethics also has important implications for the ethical foundations of psychotherapy. It suggests that moral norms are not fixed absolutes but the product of inclusive and egalitarian dialogue among all affected parties. As such, ethical practice requires not just adherence to pre-established codes but ongoing reflection and negotiation in the context of each unique therapeutic relationship.

This dialogical approach to ethics challenges the paternalism and power imbalances that have often characterized the history of psychotherapy. It calls for a more collaborative and transparent decision-making process that respects the client’s autonomy and agency. At the same time, it recognizes the inherent asymmetry of the therapeutic relationship and the need for clear boundaries and safeguards against exploitation.

Habermas’s theory also sheds light on the linguistic and narrative dimensions of therapy. It suggests that psychological distress is often rooted in distorted or constrained patterns of communication that limit the client’s ability to make sense of their experience and navigate their social world. Therapy can thus be understood as a process of “narrative repair” in which client and therapist work together to reconstruct more coherent and empowering stories.

This narrative focus is particularly relevant in the context of trauma and other experiences that shatter the continuity of the self. By helping clients integrate traumatic memories into a meaningful life story, therapy can facilitate the process of post-traumatic growth and resilience. It can also contribute to the larger cultural work of collective meaning-making in the face of historical trauma and social upheaval.

At the same time, Habermas’s theory cautions against the dangers of narrative foreclosure and the imposition of dominant cultural scripts. It emphasizes the need for a critical and reflexive approach to storytelling that interrogates the power dynamics and ideological assumptions that shape our sense-making. Therapy must create space for alternative and marginalized narratives to emerge and for clients to author their own unique stories.

This points to the importance of cultural competence and social justice in psychotherapy. Therapists must be attuned to the ways in which race, class, gender, sexuality, and other forms of difference shape the client’s experience and the therapeutic relationship itself. They must also be willing to examine their own biases and blind spots and to use their privilege in the service of empowerment and liberation.

Habermas’s concept of the lifeworld as the background of shared meanings and taken-for-granted assumptions that structure our everyday experience also has important implications for therapy. It suggests that psychological distress often arises when the lifeworld is “colonized” by the instrumental rationality of the economic and administrative systems, leading to a loss of meaning and autonomy.

Therapy can serve as a space for the rehabilitation of the lifeworld and the reclaiming of the client’s agency and authenticity. By helping clients to articulate their own values, beliefs, and desires, and to resist the conformist pressures of the system, therapy can contribute to the larger project of cultural renewal and social transformation.

At the same time, Habermas’s theory reminds us that the lifeworld is not a pre-given reality but a social construct that is always in process. As such, therapy must be attentive to the ways in which the client’s lifeworld is shaped by their social location and cultural context. It must also be open to the possibility of mutual learning and transformation, in which the therapist’s own lifeworld is expanded and enriched through the encounter with difference.

This points to the need for a more dialogical and collaborative approach to therapy that blurs the boundaries between expert and client, healer and healed. It suggests that therapy is not a one-way process of intervention but a mutual exploration of the human condition in all its complexity and mystery. As such, it requires a stance of humility, curiosity, and openness on the part of the therapist, as well as a willingness to be changed by the encounter.

Habermas’s theory also sheds light on the role of the body in therapy. While his work is primarily focused on language and communication, he acknowledges the embodied nature of human experience and the ways in which the body is inscribed by social and cultural forces. This suggests that therapy must attend not just to the client’s verbal narratives but to their somatic experience and non-verbal communication.

Embodied approaches to therapy such as somatic experiencing, sensorimotor psychotherapy, and dance/movement therapy resonate with Habermas’s emphasis on the pre-reflective and pre-linguistic dimensions of experience. They recognize that trauma and other forms of psychological distress are often stored in the body and that healing requires a holistic approach that integrates mind, body, and spirit.

At the same time, Habermas’s theory cautions against a reductive or essentialist view of the body as a pre-cultural given. It reminds us that our embodied experience is always mediated by language, culture, and power, and that the body itself is a site of social and political struggle. As such, therapy must be attentive to the ways in which the client’s bodily experience is shaped by oppressive social norms and practices, and to the liberatory potential of embodied resistance and creativity.

Implications for the Future of Depth Psychology and Psychotherapy:

Habermas’s communicative paradigm offers a powerful framework for rethinking the theory and practice of depth psychology and psychotherapy in the 21st century. It challenges the individualistic and instrumentalist biases of much contemporary therapy and points towards a more dialogical, collaborative, and socially engaged approach.

At the same time, it raises important questions about the role and identity of therapists in a postmodern and pluralistic world. If therapy is fundamentally a process of co-creation and mutual understanding, what becomes of the therapist’s expertise and authority? How do we balance the need for clear boundaries and ethical standards with the call for a more egalitarian and transparent therapeutic relationship?

These are not easy questions to answer, but they are crucial for the future of the field. As the global crises of our time continue to deepen, the need for a depth psychology that can speak to the existential and spiritual dimensions of human experience has never been greater. At the same time, the rise of digital technologies and the decentralization of knowledge are challenging the traditional models of therapeutic training and practice.

In this context, Habermas’s theory offers a way forward that is both grounded in the best of the depth psychological tradition and open to the emerging realities of the 21st century. It suggests that the future of therapy lies not in the mastery of techniques or the accumulation of expertise but in the cultivation of communicative competence, ethical reflection, and cultural transformation.

This will require a fundamental rethinking of therapeutic education and training, with a greater emphasis on critical theory, social justice, and intercultural dialogue. It will also require a more active engagement with the social and political dimensions of mental health, and a willingness to challenge the structural inequalities and cultural narratives that shape our individual and collective struggles.

At the same time, it will require a renewed commitment to the transformative power of human connection and the healing potential of authentic dialogue. In an age of increasing polarization and fragmentation, the task of building bridges of understanding and solidarity has never been more urgent. As therapists, we have a unique opportunity and responsibility to contribute to this larger cultural work.

This means creating spaces of safety and trust where people can come together across differences to share their stories and struggles, to listen deeply to each other’s pain and hopes, and to imagine new possibilities for living together on this planet. It means cultivating the skills and sensibilities of empathy, curiosity, humility, and creativity that are essential for navigating the complexities of our time.

It also means being willing to confront our own shadows and blind spots, to examine the ways in which we are complicit in the very structures of oppression and domination that we seek to transform. This requires an ongoing process of self-reflection and social critique, in which we continually interrogate our own assumptions and biases and work to align our practice with our deepest values and commitments.

Ultimately, the future of depth psychology and psychotherapy in the light of Habermas’s thought is not just about healing individuals but about building a more just and sustainable world. It is about nurturing the seeds of a new culture that is more dialogical, participatory, and life-affirming, one that honors the dignity and agency of all beings and the sacredness of the earth itself.

This is no small task, but it is one that we cannot afford to ignore. As the poet Rainer Maria Rilke reminds us, “The future enters into us, in order to transform itself in us, long before it happens.” May we have the courage and compassion to open ourselves to this transformative work, and to be the change we wish to see in the world.

In summary, Habermas offers a rich and provocative framework for reimagining the theory and practice of depth psychology and psychotherapy in the 21st century. His communicative paradigm challenges us to move beyond individualistic and instrumental approaches towards a more dialogical, relationally engaged, and socially transformative model. While raising important questions and dilemmas, his ideas point towards a future in which therapy can play a vital role in building a more just, compassionate, and sustainable world. As we grapple with the crises of our time, may we have the courage to embrace this vision and to be the healing change we wish to see.

Metamodernism and Post Secularism

Navigating the Future of Meta Modern Therapy

Bibliography:

Habermas, J. (1984). The Theory of Communicative Action, Volume 1: Reason and the Rationalization of Society. Boston: Beacon Press.

Habermas, J. (1987). The Theory of Communicative Action, Volume 2: Lifeworld and System: A Critique of Functionalist Reason. Boston: Beacon Press.

Habermas, J. (1990). Moral Consciousness and Communicative Action. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Habermas, J. (1996). Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Habermas, J. (2001). The Postnational Constellation: Political Essays. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Habermas, J. (2008). Between Naturalism and Religion: Philosophical Essays. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Habermas, J. (2015). The Lure of Technocracy. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Honneth, A., & Joas, H. (Eds.). (1991). Communicative Action: Essays on Jürgen Habermas’s The Theory of Communicative Action. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Ingleby, D. (1991). Critical Psychiatry: The Politics of Mental Health. New York: Free Press.

Kusch, M. (2018). Habermas: A Biography. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Levin, D. M. (1987). Pathologies of the Modern Self: Postmodern Studies on Narcissism, Schizophrenia, and Depression. New York: New York University Press.

Nenon, T. (2014). Language and Communication: Habermas and Wittgenstein. In J. G. Finlayson & F. Freyenhagen (Eds.), Habermas and Rawls: Disputing the Political (pp. 127-146). New York: Routledge.

Orange, D. M. (2011). The Suffering Stranger: Hermeneutics for Everyday Clinical Practice. New York: Routledge.

Ricoeur, P. (1986). Lectures on Ideology and Utopia. New York: Columbia University Press.

Stolorow, R. D., & Atwood, G. E. (1992). Contexts of Being: The Intersubjective Foundations of Psychological Life. Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press.

Sugarman, J., & Martin, J. (2018). The Sociocultural Turn in Psychology: The Contextual Emergence of Mind and Self. New York: Columbia University Press.

Taylor, C. (1989). Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Vetlesen, A. J. (1994). Perception, Empathy, and Judgment: An Inquiry into the Preconditions of Moral Performance. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Whitebook, J. (1995). Perversion and Utopia: A Study in Psychoanalysis and Critical Theory. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Young-Bruehl, E. (1998). Subject to Biography: Psychoanalysis, Feminism, and Writing Women’s Lives. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

0 Comments