The 19th century German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer is renowned for his profound and often controversial views on the nature of reality, ethics, aesthetics, and the human condition. Among his most intriguing and influential ideas are his reflections on the phenomena of madness and genius, which he saw as two sides of the same coin – deviations from ordinary cognition that reveal deeper truths about the mind and the world.

Schopenhauer’s perspective on these topics was deeply rooted in his overarching metaphysical and psychological framework, which emphasized the primacy of the Will – a blind, irrational, and ceaselessly striving force that underlies all of nature, including human behavior and consciousness. In Schopenhauer’s view, our intellect or Reason is not the master of our being, but rather a mere servant of the Will, which it seeks to satisfy through our thoughts and actions (Schopenhauer, 1818/1966).

This fundamental insight led Schopenhauer to develop a fascinating and highly original theory of madness and genius, which not only shaped his own philosophical system and his notorious rivalry with Hegel, but also anticipated key ideas in depth psychology, trauma theory, and modern cognitive neuroscience. By examining Schopenhauer’s views through the lens of contemporary research and clinical practice, we can uncover valuable insights for conceptualizing and treating psychological distress, as well as fostering resilience and even moments of “genius” in our patients’ lives.

Central to Schopenhauer’s theory was the idea that both madness and genius involve a breakdown or disruption of the normal relationship between our immediate sensory perceptions and our abstract, rational understanding of the world, which is mediated by memory. In ordinary cognition, our mind constantly integrates the raw data of our senses with our pre-existing concepts, beliefs, and autobiographical memories, creating a coherent and meaningful picture of reality that enables us to function in society and pursue our goals (Schopenhauer, 1851/1974).

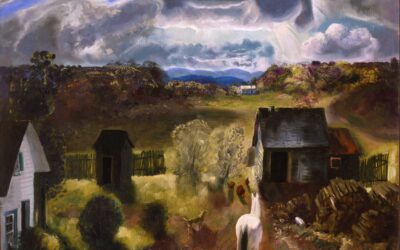

However, in madness, Schopenhauer argued, this delicate balance is disrupted: the thread of memory is severed, and the individual becomes trapped in a fragmented, disconnected present, unable to make sense of their experiences or maintain a stable sense of self over time. The result is a profound alienation from the shared world of culture and convention, as well as a loss of the “rational continuity of consciousness” that defines sanity (Schopenhauer, 1851/1974, p. 124).

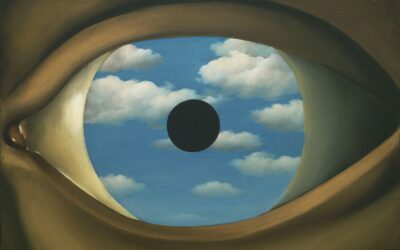

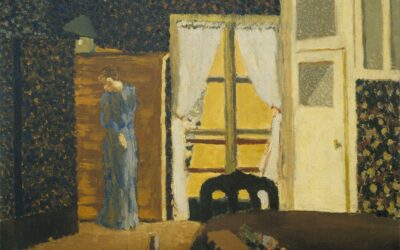

Conversely, in moments of genius or aesthetic contemplation, the individual temporarily breaks free from the constraints of memory and reason, achieving a pure, will-less perception of the world as it truly is, beyond the veil of our pragmatic concepts and categories. In such states, Schopenhauer claimed, we directly apprehend the eternal Platonic Ideas that constitute the timeless essence of things, rather than their mere spatial and temporal representations (Schopenhauer, 1818/1966, p. 178).

While this theory may seem abstract and speculative, it contains a number of remarkably prescient insights that resonate with contemporary research on the neurobiology and psychology of trauma, dissociation, and altered states of consciousness. As we will see, Schopenhauer’s model of madness as a “fragmentation” of memory and self-experience strikingly anticipates the dissociation theory of trauma developed by Pierre Janet, Freud, and others in the early 20th century (Van der Hart & Horst, 1989).

Similarly, his emphasis on the irrational, unconscious depths of the psyche foreshadows Freud’s topographic model of the mind, as well as modern neuroscientific accounts of the “adaptive unconscious” and its role in shaping cognition and behavior (Wilson, 2002). And his notion of genius as a “pure” perception freed from the fetters of memory and self suggests intriguing parallels with recent research on the neurocognitive bases of creativity, insight, and flow states (Dietrich, 2004).

Moreover, Schopenhauer’s ideas also have important implications for clinical practice, particularly in the treatment of trauma and dissociative disorders. His model suggests that a key goal of therapy should be to help patients restore a coherent narrative that connects their present experiences with their autobiographical past, thereby overcoming the temporal fragmentation and derealization that characterize traumatic memory (Van der Kolk & Van der Hart, 1995).

This process of integration and contextualization is strikingly similar to the mechanism of memory reconsolidation that is now believed to underlie the efficacy of exposure-based and experiential therapies for PTSD and related conditions (Lane et al., 2015). By revisiting and re-encoding traumatic memories in a safe and supportive context, patients can gradually weave them into a more adaptive and empowering life story, regaining a sense of continuity and agency (Ecker et al., 2012).

At the same time, Schopenhauer’s aesthetics of genius also suggest that there may be value in helping patients cultivate their capacity for immersive, self-transcendent states of awareness, whether through art, nature, meditation, or other means. By learning to occasionally quiet the chatter of the ego and the tyranny of the will, individuals may access deeper sources of creativity, meaning, and embodied wisdom that can foster resilience and post-traumatic growth (Kalsched, 2013).

Of course, this is not to romanticize madness or pathologize ordinary consciousness, but rather to recognize the complex dialectic between reason and un-reason, memory and immediate experience, that shapes both our struggles and our epiphanies. As the mythologist Joseph Campbell eloquently put it, “the psychotic drowns in the same waters in which the mystic swims with delight” (Campbell, 1972, p. 208) – an insight that Schopenhauer would deeply appreciate.

In the following sections, we will unpack these themes in greater depth, exploring how Schopenhauer’s philosophy of madness and genius can inform our understanding of trauma, dissociation, creativity, and the therapeutic process. Through this dialogue between 19th century metaphysics and 21st century science, we may catch a glimpse of the enduring wisdom and clinical relevance of Schopenhauer’s thought.

1. Madness as Memory Fragmentation

Central to Schopenhauer’s worldview was the notion that Will, not intellect, is the driving force of human experience. He saw the mind as fundamentally irrational, with reason merely serving, rather than truly governing, our baser drives. This led him to a striking theory of madness:

Madness arises when the thread of memory is broken – when the mind fails to integrate present perceptions with the totality of past experience. The ‘I’ loses coherence over time, leaving one trapped in a disjointed present without rational continuity.

In madness, Schopenhauer claimed, a person’s sense of self fragments as their memory fails to contextualize immediate experience. Remarkably, this idea foreshadows the dissociative model of trauma, in which overwhelming experiences are inadequately encoded and integrated into autobiographical memory.

2. The Rarity of True Genius

In contrast to madness, Schopenhauer regarded genius as an exceedingly rare state of heightened perception, unfiltered by egoistic concerns:

The genius directly apprehends the Platonic Ideas – the timeless essences behind shifting appearances. Lost in aesthetic contemplation, liberated from the Will, they perceive an undistorted reality.

While the “normal” mind aligns all perception with self-interest, genius involves a temporary silencing of desire and practical concern. Nietzsche would later challenge this “ascetic” view, but Schopenhauer saw it as the key to objective knowledge and artistic brilliance.

3. The Hegel Rivalry: Systematizer vs. Sage

Schopenhauer’s influential dichotomy between genius and intellectual fakery fueled his disdain for Hegel. He accused his rival of pseudo-profundity – of erecting conceptual castles to conceal a lack of genuine insight:

Hegel’s dialectics are the mere semblance of philosophy, serving only to mystify and stupefy. True genius speaks clearly; it has no need for Hegelian jargon.

Where Hegel sought to systematize knowledge into a historical metanarrative, Schopenhauer valued the untimely genius who illuminated eternal truths. This preference for poetic wisdom over methodical abstraction would later inspire existential thinkers like Kierkegaard and Nietzsche.

4. Trauma, Dissociation, and the Irrational Unconscious

Strikingly, Schopenhauer’s model of madness as a breakdown of memory integration directly anticipates the dissociation theory of trauma developed by Janet, Freud, Breuer and others. In PTSD, as in Schopenhauerian madness, experience falls out of temporal context, leaving one haunted by unintegrated sensations and fragments of memory.

The traumatized psyche is thrust into a timeless present, reliving an undigested past as if it were still occurring. The thread of memory is broken; the ‘I’ knows not how it arrived in this moment.

Schopenhauer’s emphasis on the irrational Will also presaged Freud’s notion of the unconscious – a realm of conflicting drives and repressed experiences beneath the veneer of reason. Both thinkers recognized that apparently meaningless phenomena (dreams, neurotic symptoms, etc.) express a hidden psychological logic.

5. Filtering vs. Generating: Attention as Suppression

Recent research on sensory gating suggests that the prefrontal cortex does not “produce” thought so much as constrain and inhibit subcortical activity. In other words, what we experience as rational cognition is largely a process of filtering and exclusion:

The cortex is a dam holding back the flood of raw sensation and chaotic impulse bubbling up from older brain regions. ‘Mindfulness’ consists in selectively lowering this dam – letting more of the unconscious enter awareness.

This updating of the Freudian model is highly consistent with Schopenhauer’s framework. If the unconscious Will is vastly richer in information than our conscious models, then perception itself always involves a restrictive narrowing. The artist may swim in this sensory stream; the schizophrenic drowns.

6. Restoring Continuity: Memory Reconsolidation in Therapy

Schopenhauer’s insights into madness and memory fragmentation point to a key challenge in therapy: helping patients restore a coherent narrative that connects past and present. The emerging science of memory reconsolidation offers a framework for this:

In states of emotional arousal, old memories become labile and susceptible to modification. By evoking traumatic memories in a safe context, we can strip away their dissociative terror and reintegrate them.

As we revisit charged memories with empathy and grounding, the hippocampus re-encodes these experiences, updating their emotional significance. Gradually, clients move from a shattered, decontextualized ‘eternal present’ to a meaning-making narrative that links feeling to autobiographical memory.

References

Schopenhauer, A. (1966). The world as will and representation (E. F. J. Payne, Trans.). Dover. (Original work published 1818)

Schopenhauer, A. (1974). Parerga and paralipomena: Short philosophical essays (E. F. J. Payne, Trans.). Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1851)

Van der Hart, O., & Horst, R. (1989). The dissociation theory of Pierre Janet. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 2(4), 397-412.

Wilson, T. D. (2002). Strangers to ourselves: Discovering the adaptive unconscious. Harvard University Press.

Dietrich, A. (2004). The cognitive neuroscience of creativity. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 11(6), 1011-1026.

Van der Kolk, B. A., & Van der Hart, O. (1995). The intrusive past: The flexibility of memory and the engraving of trauma. In C. Caruth (Ed.), Trauma: Explorations in memory (pp. 158-182). Johns Hopkins University Press.

Lane, R. D., Ryan, L., Nadel, L., & Greenberg, L. (2015). Memory reconsolidation, emotional arousal, and the process of change in psychotherapy: New insights from brain science. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 38, e1.

Ecker, B., Ticic, R., & Hulley, L. (2012). Unlocking the emotional brain: Eliminating symptoms at their roots using memory reconsolidation. Routledge.

Kalsched, D. (2013). Trauma and the soul: A psycho-spiritual approach to human development and its interruption. Routledge.

Campbell, J. (1972). Myths to live by. Viking Press.

Tags

0 Comments