The Psychology of Romantic Architecture

What is Romantic Architecture?

Romantic architecture, emerging in the late 18th century and flourishing through the 19th century, represents a departure from the strict rationalism of Neoclassicism. This movement, characterized by its emphasis on emotion, nature, and the picturesque, sought to create buildings that stirred the imagination and evoked strong feelings. In this exploration, we’ll delve into the origins, characteristics, and psychological underpinnings of Romantic architecture.

Historical Context and Key Characteristics

Romantic architecture developed alongside the broader Romantic movement in arts and literature. Key characteristics include:

- Asymmetrical compositions

- Integration with natural surroundings

- Use of local and rustic materials

- Revival of medieval styles (overlapping with Gothic Revival)

- Emphasis on the picturesque and sublime

- Inclusion of ruins or artificial weathering

- Eclectic mix of historical styles

Cultural Context

The rise of Romantic architecture coincided with a period of significant cultural and social change. The Enlightenment’s emphasis on reason and order was giving way to a new appreciation for emotion, imagination, and individuality. The Industrial Revolution was transforming the landscape and the way people lived, leading to a sense of nostalgia for a simpler, more natural past. Romantic architecture reflected these cultural shifts, offering a means of escape from the increasingly mechanized and urbanized world.

Technological Advances

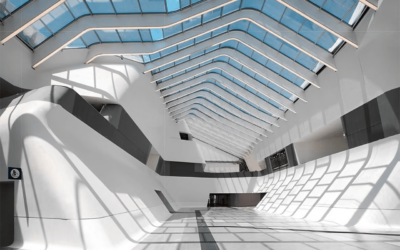

While Romantic architecture often drew inspiration from the past, it also benefited from technological advances of the time. The development of cast iron and glass allowed for the creation of more spacious and light-filled interiors, as seen in the works of architects like John Nash and Joseph Paxton. Improvements in transportation and communication also made it easier for architects to travel and study historical buildings, leading to a more eclectic and historically informed approach to design.

Political Landscape

The political landscape of the late 18th and early 19th centuries was marked by the rise of nationalism and the struggle for individual rights and freedoms. Romantic architecture often served as a means of expressing national identity and pride, as seen in the revival of vernacular styles and the use of local materials. The style also reflected the growing power and influence of the bourgeoisie, who sought to distinguish themselves from the aristocracy through their patronage of the arts and their embrace of more individualistic and expressive forms of architecture.

Key Innovators

Several influential architects and designers were at the forefront of the Romantic movement, including:

John Nash: British architect known for his picturesque country houses and his work on Regent’s Park and Regent Street in London.

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin: British architect and designer who was a leading proponent of the Gothic Revival style, known for his work on the Houses of Parliament in London.

Karl Friedrich Schinkel: Prussian architect and painter who designed a number of influential Neoclassical and Romantic buildings, including the Altes Museum in Berlin.

Claude Nicholas Ledoux: French architect known for his visionary and often fantastical designs, such as the Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans.

Related Architectural Styles

Romantic architecture is closely related to and often overlaps with other architectural styles of the 18th and 19th centuries, including:

Gothic Revival: A style that drew inspiration from medieval Gothic architecture, characterized by pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and ornate decoration.

Picturesque: An aesthetic ideal that emphasized the beauty of irregularity, asymmetry, and natural forms in architecture and landscape design.

Eclecticism: A design approach that freely combined elements from different historical styles, often in a playful or fanciful manner.

Dialectical Materialist Perspective

From a dialectical materialist viewpoint, Romantic architecture represents a synthesis of:

- Reaction against Enlightenment rationalism

- Response to early industrialization and urbanization

- Nationalist movements seeking authentic cultural expression

- Changing class dynamics with the rise of the bourgeoisie

The style emerged from the contradiction between the desire for order and reason and the longing for emotion and individuality. It embodied the tension between the pursuit of progress and the nostalgia for a simpler, more natural past.

Jungian Depth Psychology Analysis

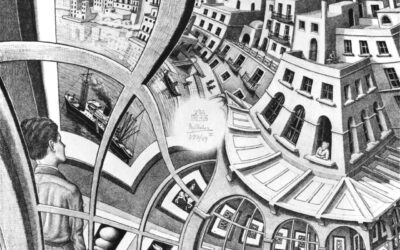

Through a Jungian lens, Romantic architecture embodies:

- The Collective Unconscious: Tapping into shared cultural memories and myths

- The Nature Archetype: Emphasizing connection with the natural world

- The Child Archetype: Evoking wonder, imagination, and innocence

The emphasis on emotion, nature, and the picturesque in Romantic architecture can be seen as an expression of the Collective Unconscious, drawing on shared cultural memories and myths to create spaces that resonate with the human psyche. The integration of buildings with their natural surroundings and the use of organic forms and materials reflect the Nature Archetype, representing the human desire for connection with the natural world. The sense of wonder and imagination evoked by Romantic architecture can be interpreted as a manifestation of the Child Archetype, representing the innocence and creativity of the human spirit.

Ego Perspective: Assertions and Insecurities

Romantic architecture served to:

- Assert the primacy of emotion and imagination over reason

- Project a connection with nature and the past

- Express individualism and national identity

It also revealed insecurities about:

- Loss of connection with nature in increasingly urban societies

- Fear of cultural homogenization due to industrialization

- Anxiety about rapid social and technological changes

The emphasis on emotion, nature, and the picturesque in Romantic architecture can be seen as an assertion of the value of individual experience and expression, as well as a projection of a deep connection with the natural world and the cultural past. However, the style also revealed underlying insecurities about the impact of industrialization and urbanization on human society and culture, as well as anxieties about the rapid pace of social and technological change.

Lasting Influence, Criticisms, and Modern Context

While pure Romantic architecture is rare today, its influence can be seen in various revival styles, landscape design, and in architecture that emphasizes emotional impact and integration with nature. The style has been criticized for its sometimes fanciful or impractical designs, as well as for its association with a nostalgic or escapist view of the past. However, its legacy lies in challenging the notion that architecture should be purely rational or functional, paving the way for more expressive and individualistic approaches to design.

In the modern context, the principles of Romantic architecture continue to inspire architects and designers who seek to create spaces that evoke emotion, connect with nature, and celebrate cultural heritage. The style’s emphasis on the picturesque and the sublime has influenced the development of landscape architecture and the design of public parks and gardens. At the same time, the social and political implications of the style continue to be debated, as architects and planners grapple with issues of authenticity, identity, and the role of history in shaping the built environment.

Bibliography and Further Reading

- Bergdoll, B. (2000). European Architecture 1750-1890. Oxford University Press.

- Brooks, C. (1999). The Gothic Revival. Phaidon Press.

- Colquhoun, A. (1991). Essays in Architectural Criticism: Modern Architecture and Historical Change. MIT Press.

- Honour, H. (1981). Romanticism. Harper & Row.

- Hvattum, M. (2004). Gottfried Semper and the Problem of Historicism. Cambridge University Press.

- Mallgrave, H. F. (2005). Modern Architectural Theory: A Historical Survey, 1673-1968. Cambridge University Press.

- Mowl, T. (1993). Stylistic Cold Wars: Betjeman Versus Pevsner. John Murray.

- Trachtenberg, M., & Hyman, I. (1986). Architecture: From Prehistory to Post-Modernism. H.N. Abrams.

Read about the Psychology of Other Styles of Architecture

The Psychology of Architecture

The Psychology of Architecture

0 Comments