A Deep Dive into Will Selman’s Revolutionary Book

Bridging Ancient Wisdom and Modern City Design

In an era where cities face unprecedented challenges—from climate change to social disconnection—urban planner and author Will Selman presents a compelling vision in his groundbreaking book “Temenos.” Drawing from Carl Jung’s psychological theories, sacred geometry principles, and the forgotten wisdom behind Washington D.C.’s original design, Selman argues that our urban spaces can be transformed from soulless concrete jungles into meaningful, spiritually-enriching environments that foster both individual and collective growth.

The Hidden Sacred Geometry of Washington D.C.: Pierre L’Enfant’s Forgotten Vision

The Architect Behind America’s Capital

Pierre L’Enfant, the French-born architect who designed Washington D.C., was far more than a city planner—he was a visionary who embedded profound spiritual and psychological meaning into America’s capital. Raised in Versailles as the son of a court artist under Louis XIV, L’Enfant possessed deep knowledge of classical art, design principles, and sacred geometry that most educated people of his era understood but which has been largely forgotten today.

L’Enfant’s Revolutionary Design Philosophy

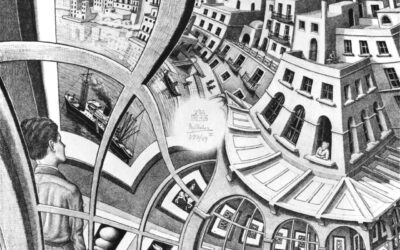

Unlike European cities where all roads led to the king’s palace, L’Enfant created something unprecedented: a geometric trellis that distributed power across multiple centers. The Capitol Building, representing “the earth and its people,” sits at the heart of a five-pointed star pattern formed by major avenues like Pennsylvania and Massachusetts. Meanwhile, the White House, symbolizing “the gods in heaven” or divine authority, anchors an equilateral triangle formed by Connecticut and Vermont Avenues.

This wasn’t mere aesthetic choice—it was a deliberate attempt to reconcile the tension between heavenly aspiration and earthly politics, between divine authority and democratic governance. As Selman explains, this represents the fundamental challenge of civilization: “How do you balance those two—both in yourself, your personal life, and as a nation, as a culture, as a civilization?”

The Lost Language of Sacred Geometry

The numbers and shapes L’Enfant employed carried specific meanings rooted in ancient wisdom:

- The Number Five represented the earth and its people

- The Number Six symbolized the gods or divine authority

- Geometric patterns like the vesica piscis (formed by two overlapping circles) represented the reconciliation of opposites

This wasn’t “secret Masonic symbolism” as conspiracy theorists suggest, but common knowledge among educated people of the 18th century. The tragedy, according to Selman, is that “it’s only secret now because we dispensed with it—we forgot it.”

Carl Jung’s Psychology Meets Urban Planning: The Theoretical Foundation

The Three Phases of Human Psychological Development

Selman’s approach to urban planning is deeply influenced by Carl Jung’s theories of psychological development, which he applies to both individual and civilizational growth:

- The Religious/Mythological Phase: Humanity’s childhood, when we lived within sacred cosmologies that provided meaning and structure

- The Scientific Revolution Phase: Our adolescent rebellion, beginning in the 1600s, where we broke away from traditional wisdom to establish intellectual autonomy

- The Integration Phase: The mature synthesis we must now achieve, combining scientific knowledge with spiritual wisdom

America as a “Psychologically Immature Culture with Powerful Tools”

Jung himself was reportedly concerned about America, seeing it as having “so much power and capability in a very psychologically immature culture.” Selman argues that America, born during the Scientific Revolution, was “one of the first countries built solely on” the rationalist, technological worldview—making it both uniquely powerful and uniquely disconnected from deeper sources of meaning.

The Crisis of Modern Architecture and Urban Design

From Sacred Spaces to Soulless Structures

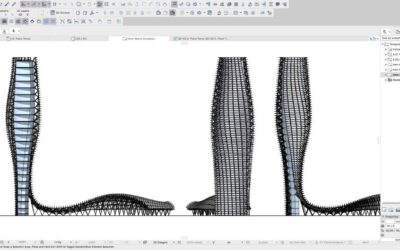

Modern architecture and urban planning have largely abandoned the principles that made spaces meaningful and beautiful. Where Frank Lloyd Wright could integrate natural patterns, human function, and spiritual purpose, contemporary architects are often expected to “reinvent a new process every time,” creating buildings that are merely different rather than meaningful.

The Loss of Institutional Knowledge

Selman draws a parallel between modern architecture and America’s loss of manufacturing capability: “We don’t make anything, and we don’t have that knowledge [that] is institutional.” Just as we can no longer easily recreate the Saturn V rocket despite having built it decades ago, we’ve lost the accumulated wisdom of traditional building crafts and design principles.

Finance Drives Form: The Economic Roots of Poor Design

A crucial insight from Selman’s analysis is how financial structures shape our built environment. The old adage “form follows function” has been replaced by “form follows finance.” When developers prioritize short-term profits over long-term value, when planned obsolescence drives consumer culture, and when everything becomes disposable, our cities reflect these values—becoming disposable themselves.

The IKEA Economy and Its Architectural Consequences

Selman references IKEA’s Swedish advertisement showing a discarded lamp with sad music, followed by the message: “Don’t feel bad for the lamp… you can get a new one.” This disposable mentality has infected not just consumer goods but our approach to buildings, neighborhoods, and entire urban districts.

Practical Solutions: From Shopping Malls to Sacred Neighborhoods

The Lancaster Pennsylvania Experiment

As chairman of the City Planning Commission in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Selman conducted a real-world experiment in applying L’Enfant’s methodology to modern challenges. Faced with a struggling shopping mall that had lost 60% of its stores, he developed a plan to transform the 200-acre site into a walkable neighborhood using sacred geometric principles.

Creating a Modern “Trellis”

Following L’Enfant’s example, Selman created an underlying geometric framework that determined:

- Street patterns connecting different areas

- Locations for civic buildings (library, city hall, schools)

- Placement of parks and community gardens

- A network of “dispersed civic commons” that keeps residents connected to community life

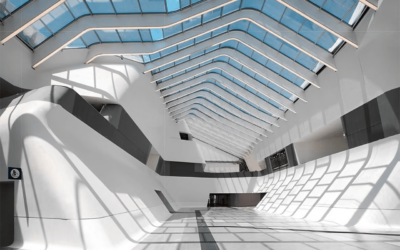

The “Stations of the Cross” Concept for Cities

Drawing from his Episcopal upbringing, Selman proposes expanding the church concept of “Stations of the Cross”—a series of meaningful stopping points that tell a story—throughout entire cities. These would be “points of inspiration and learning along a path” that could include:

- Open spaces connected thematically

- Civic structures that serve community needs

- Community gardens and gathering places

- Art installations and monuments that provoke reflection

The goal is to create urban environments where “you’re walking from one place to another but you’re always a part of the community.”

Preparing for Future Challenges: Climate Change and Urban Resilience

The Coming Wave of Climate Refugees

Selman acknowledges that cities must prepare for massive demographic shifts due to climate change. With sea-level rise threatening coastal cities like Miami and New York, millions of people will need to relocate to more stable inland areas. The challenge is avoiding the creation of “future slums” by responding thoughtfully rather than in panic mode.

Strategic Urban Planning for Receiver Cities

Communities in climatically stable areas (Selman suggests central Michigan as an example) have an opportunity to prepare infrastructure that can accommodate climate refugees while maintaining quality of life and community cohesion. This requires long-term thinking and the kind of meaningful urban design principles he advocates.

The Institute for Symbolic Urbanism: Building the Future

A New Movement in Urban Planning

Selman is establishing the Institute for Symbolic Urbanism to develop and refine these ideas into practical applications. This nonprofit organization aims to create “a new way of thinking about and doing urbanism” that integrates Jungian psychology, sacred geometry, and sustainable design principles.

The institute represents a potential evolution beyond the Congress for New Urbanism, incorporating lessons learned from recent challenges like the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on downtown office spaces and the ongoing transformation of retail landscapes.

Lessons from History: Jefferson vs. Washington’s Urban Visions

Two Competing American Philosophies

The book illuminates a fascinating tension between Thomas Jefferson and George Washington’s visions for America:

Jefferson’s Agrarian Ideal: Believing cities were inherently corrupt, Jefferson advocated for a nation of independent farmers living on 160-acre plots. His grid system still shapes much of the American Midwest, but Selman points out the contradiction: Jefferson himself depended on European cities for the luxury goods he imported while condemning urban life.

Washington’s Imperial Vision: Understanding that America had the potential to become a global superpower, Washington embraced the need for magnificent cities that could inspire and educate. He saw the capital as a symbol of the “new world order” (novus ordo seclorum) that America represented.

The Symbolism of Street Layouts

Even small details in L’Enfant’s design carried meaning: streets don’t terminate at the center of important buildings but at their doorways, symbolically communicating that “people are welcome here.” This contrasts sharply with Versailles, where all paths led to the king’s bedroom, emphasizing absolute monarchy rather than democratic accessibility.

The Spiritual Dimension of Urban Planning

Beyond Mere Functionality

Selman argues that humans are driven to create not just for practical reasons but for “metaphorical reasons”—expressing concepts and ideas that “don’t help us survive but we think make life better somehow.” This drive distinguishes human settlement patterns from animal habitats and explains why early cities often made life materially harder while providing spiritual and psychological benefits.

Religion as a “Container”

Drawing on insights about religion serving as a protective container for psychological development, Selman suggests that well-designed urban spaces can serve similar functions—providing structure and meaning that help individuals and communities mature psychologically rather than remain trapped in adolescent rebellion against all traditional wisdom.

Overcoming the Modern Crisis of Meaning

The Nietzschean Problem

Selman references Nietzsche’s famous declaration that “God is dead,” noting that most people misunderstand this as a call to liberation when Nietzsche actually saw it as a disaster. Without transcendent meaning, society loses its center and fragments—leading to the catastrophic conflicts of the 20th century.

The Search for New Sources of Meaning

The challenge for contemporary urban planners is creating spaces that provide meaning without simply returning to outdated religious or political forms. Selman’s approach suggests that sacred geometry and thoughtful design can serve this function, creating environments that connect people to something larger than themselves while respecting modern democratic and scientific values.

Practical Implementation: Design Principles for the 21st Century

Elements of Symbolic Urbanism

Based on the Congress for New Urbanism charter and his own innovations, Selman outlines key design elements:

- Walkable neighborhoods with mixed-use development

- Geometric frameworks that organize space meaningfully

- Civic commons spaces distributed throughout communities

- Transit-oriented development reducing car dependency

- Green infrastructure integrating natural systems

- Historic preservation maintaining connection to the past

- Affordable housing ensuring economic diversity

Financing Reform

Understanding that “form follows finance,” Selman emphasizes the need for new financing mechanisms that prioritize long-term community value over short-term profits. This might include:

- Community land trusts maintaining affordability

- Value capture mechanisms funding public improvements

- Patient capital allowing longer development timelines

- Social impact bonds rewarding community benefits

The Global Context: Learning from International Examples

Medieval Towns and Modern Applications

Selman references the Italian fortified town of Palmanova, built in a star pattern with a moat, as an example of how geometric principles have been successfully applied to urban design throughout history. Such examples provide templates for contemporary applications while respecting local contexts and modern needs.

European vs. American Development Patterns

The transcript reveals how America’s unique circumstances—vast land resources, patent-stealing industrial espionage, and democratic ideals—created different urban development patterns than Europe. Understanding these historical forces helps explain current challenges and opportunities for reform.

Technology and Tradition: Finding Balance

The AI Parallel

Selman draws parallels between current concerns about artificial intelligence and the broader challenge of technological change: “People are like, ‘Hey, this is kind of a bad idea,’ but we can’t quit doing it because this is the way it’s going, and if I quit doing it, I’m behind.”

This observation highlights the need for conscious choice in technological adoption rather than simply following market forces or competitive pressures.

Preserving Human-Scale Development

Against the backdrop of increasing technological complexity, symbolic urbanism emphasizes human-scale development that remains comprehensible and meaningful to residents. This doesn’t mean rejecting technology but ensuring it serves human flourishing rather than replacing human connection.

The Path Forward

Churchill’s Wisdom Applied to Urban Planning

Selman concludes with Winston Churchill’s observation: “Americans will always do the right thing after they’ve tried everything else.” While he expects resistance to change, he believes crisis will eventually force adoption of more thoughtful urban planning approaches.

The Opportunity of Our Time

For the first time in history, humanity can see major global changes coming and prepare thoughtfully rather than simply react. This presents an unprecedented opportunity to create urban environments that support both individual psychological development and collective resilience.

A Call to Action

Will Selman’s “Temenos” isn’t just theoretical speculation—it’s a practical guide for creating urban environments that nurture the human spirit while addressing contemporary challenges. As climate change, technological disruption, and social fragmentation threaten traditional urban forms, his synthesis of ancient wisdom and modern knowledge offers a path toward cities that are both sustainable and sacred.

The book challenges readers to see urban planning not as mere engineering but as a form of applied psychology and spiritual practice. In doing so, it opens possibilities for cities that don’t just house bodies but nurture souls, creating spaces where both individuals and communities can achieve their fullest potential.

Whether through transforming abandoned shopping malls, redesigning suburban sprawl, or planning entirely new communities for climate refugees, the principles outlined in “Temenos” offer hope for an urban future that honors both human needs and cosmic meaning. The question is whether we’ll embrace this wisdom proactively or wait until crisis forces our hand.

About the Book: “Temenos” by Will Selman is available through Amazon in both hardcover ($35) and ebook ($9.99) formats. The author is also establishing the Institute for Symbolic Urbanism (symbolicurbanism.org) to further develop these ideas into practical applications.

0 Comments