An Overview of Haloween and its Sweet Traditions

Candy is a central feature of modern Halloween celebrations, with trick-or-treating children gathering sweets from neighbors and stores stocking up on mini chocolate bars and gummy worms. Yet this sweet tradition has a complex history that reflects broader social, economic, and cultural shifts. The story of Halloween candy is a microcosm of changing attitudes towards food, festival, and community in American society and beyond. Tracing the origins and evolution of this sugary custom reveals the dark side of candy – the fears, myths, and moral panics that have surrounded this seemingly innocent indulgence.

At its core, candy is a symbol of joy and celebration, a rare treat that marks special occasions and indulges the sweet tooth. In the context of Halloween, candy takes on additional layers of meaning as a token of transgression, disguise, and mischief. Accepting candy from strangers is usually taboo, but on Halloween, it becomes a sanctioned ritual. Dressing up in costumes blurs the lines of identity and propriety, creating a liminal space where normal rules are suspended. In this sense, Halloween candy is not just a tasty snack, but a cultural signifier that embodies the spirit of the holiday – a night of role reversal, boundary crossing, and controlled chaos.

The Anthropology of Food and Festival

To understand the significance of Halloween candy, we must first situate it within the broader anthropological context of food and festival. In every culture, food is more than just sustenance – it is a medium of social bonding, identity expression, and meaning-making. Sharing food is a universal way of creating and maintaining social ties, whether through daily meals or special feasts. Festivals, in particular, are occasions for communities to come together and celebrate shared values, beliefs, and experiences. Food plays a central role in festival rituals, often in ways that invert or subvert everyday norms.

Candy, as a type of food, has its own cultural associations and connotations. In many societies, sugar and sweets were historically rare and expensive commodities, reserved for the wealthy or for special occasions. As such, candy became associated with luxury, indulgence, and celebration. At the same time, candy is often linked with childhood, innocence, and nostalgia. The sweet taste and bright colors of candy evoke memories of carefree days and simple pleasures. This association with childhood makes candy a potent symbol in Halloween traditions, which often revolve around children and the imagination.

The Celtic Roots of Halloween

The origins of Halloween can be traced back to the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain, which marked the end of the harvest season and the beginning of the dark winter months. Samhain was a liminal time when the veil between the world of the living and the dead was believed to be at its thinnest, allowing spirits and fairies to cross over. To appease these supernatural beings and ensure a bountiful harvest, the Celts would leave offerings of food and drink, especially at doorways and crossroads.

Over time, these offerings evolved into the practice of “guising” or “mumming,” where people would dress up in costumes and go door-to-door, reciting verses or performing tricks in exchange for food or money. This custom was particularly popular in Ireland, Scotland, and other parts of the British Isles, and often involved a mischievous or threatening element. Guisers might play pranks or demand payment, blurring the lines between good-natured fun and genuine menace.

The Christian Overlay of All Saints’ Day

As Christianity spread throughout Europe, it incorporated many pagan festivals and traditions into its own calendar. The Celtic festival of Samhain became All Saints’ Day or All Hallows’ Day, a time to honor deceased saints and pray for recently departed souls. The evening before, October 31, became known as All Hallows’ Eve or Halloween.

In medieval Britain and Ireland, “souling” became a popular practice on All Saints’ Day. Poor people, often children, would go door-to-door, offering prayers for the dead in exchange for food and drink, particularly “soul cakes” – small round cakes flavored with spices and decorated with a cross. This custom was seen as a form of charity and remembrance, with the soul cakes acting as a kind of spiritual currency. At the same time, souling had a subversive edge, with costumed beggars using the threat of mischief to extract food and money from wealthier households.

The American Adaptation of Halloween

When Irish and Scottish immigrants brought Halloween traditions to America in the 19th century, they found a ready audience in a society that was rapidly urbanizing and industrializing. In rural communities, Halloween became a time for celebrating the harvest and playing pranks, such as tipping over outhouses or unhinging fence gates. In cities, the holiday took on a more raucous and anarchic character, with gangs of young men roaming the streets and causing mayhem.

To tame these unruly celebrations, civic leaders and progressive reformers promoted a more family-friendly version of Halloween in the early 20th century. Children’s parties, with games and costumes, became the norm, and trick-or-treating emerged as a way to provide young people with a safe and controlled outlet for their energy. Early Halloween treats were often homemade, such as candied apples, popcorn balls, and fudge, reflecting the domestic ideals of the time.

After World War II, Halloween underwent another transformation, as the rise of suburbia and the baby boom created a massive market for mass-produced candy. Trick-or-treating became a national ritual, with children going door-to-door in search of prepackaged treats. Candy companies seized on the opportunity, creating special Halloween-themed products and promotions. Candy corn, which had been around since the late 19th century, became synonymous with the holiday, along with other iconic treats like Tootsie Rolls and Necco Wafers.

Candy Scares and Moral Panics

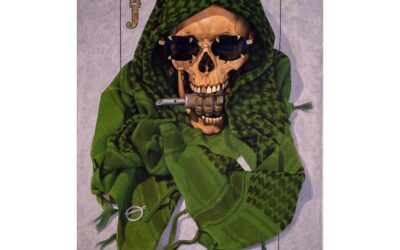

Despite its association with childhood innocence, Halloween candy has also been the subject of fear and suspicion. In the 1970s and 80s, a series of candy tampering scares swept the nation, fueled by sensationalist media coverage and urban legends. The most famous of these was the myth of razor blades hidden in apples, which became a cautionary tale for parents and a symbol of the dangers lurking in seemingly wholesome treats.

While there were a few actual cases of candy tampering, such as the 1974 Houston poisoning, in which a father killed his own son with cyanide-laced Pixy Stix, these incidents were extremely rare. However, they tapped into deep-seated anxieties about the safety of children and the trustworthiness of strangers. The widespread fear of tainted Halloween candy can be seen as a moral panic – an exaggerated and irrational response to a perceived threat, often fueled by media hype and cultural myths.

The legacy of these candy scares can still be seen in the elaborate safety precautions and packaging practices surrounding Halloween treats today. Many parents inspect their children’s candy hauls for signs of tampering, hospitals offer to X-ray candy bags, and some communities have even banned homemade treats altogether. These measures reflect a lingering sense of unease and mistrust, even as the actual risk of candy tampering remains vanishingly small.

Candy as Conflict and Controversy

Halloween candy has also been caught up in larger cultural and political debates, particularly around health, religion, and identity. In recent years, concerns about childhood obesity and diabetes have led some to question the wisdom of celebrating a holiday that revolves around sugary treats. Schools and community groups have tried to promote healthier alternatives, such as pretzels, popcorn, or even toothbrushes, with mixed success. Candy companies have responded by offering smaller portions, low-calorie options, and allergen-free varieties.

Religious and cultural objections to Halloween have also impacted the candy industry. Some conservative Christians see Halloween as a celebration of paganism, witchcraft, or even Satanism, and have called for boycotts of candy companies that promote the holiday. Others object to the commercialization and secularization of what was once a religious festival, and seek to reclaim the spiritual meanings of the season.

For some immigrant and ethnic communities, Halloween candy can be a flashpoint for debates over assimilation and cultural identity. Traditional sweets like Mexican sugar skulls or Indian laddu may be seen as out of place or even offensive in the context of American trick-or-treating. At the same time, the globalization of the candy industry has led to the cross-pollination of flavors and styles, creating new hybrid treats that reflect the diversity of modern society.

The Folklore of Halloween Candy

Despite these challenges and controversies, Halloween candy remains a beloved and enduring tradition, one that is steeped in folklore and regional variation. Every part of the country has its own favorite Halloween treats, from saltwater taffy on the Jersey Shore to candy apples in the Midwest to chili-spiced mangoes in the Southwest. These local specialties often have their own stories and legends attached, such as the belief that candy corn kernels must be eaten in a specific order (white, orange, yellow) to avoid bad luck.

Candy also plays a role in many Halloween superstitions and divination games. Bobbing for apples, a popular party activity, is said to predict who will be the first to marry, based on who successfully bites into the floating fruit. The colors of candy wrappers are sometimes used as a love oracle, with different hues corresponding to different romantic fates. And of course, there are the perennial rumors of “bad” or “unlucky” candy that should be avoided at all costs, from black licorice to Mary Janes.

These folk beliefs and practices may seem quaint or silly, but they reflect a deeper human need to imbue even the most mundane objects with meaning and magic. Halloween candy is not just a sweet treat, but a symbol of the mysteries and wonders that lurk beneath the surface of everyday life. By indulging in these sugary rituals, we reconnect with the child-like sense of enchantment and possibility that the holiday embodies.

The Future of Halloween Candy

As Halloween continues to evolve and adapt to changing times, so too does the candy that defines it. In recent years, there has been a growing interest in artisanal, handcrafted, and locally sourced sweets, as a reaction against the mass-produced uniformity of most Halloween fare. Some candy makers are experimenting with exotic flavors and ingredients, from ghost pepper caramel to black garlic chocolate, in an attempt to stand out in a crowded market.

At the same time, there is a growing awareness of the environmental and social impact of the candy industry, from the use of palm oil to the exploitation of cocoa farmers. Some consumers are seeking out more sustainable and ethical alternatives, such as organic, fair-trade, or vegan candy. Packaging, too, is coming under scrutiny, with calls for more biodegradable or recyclable materials.

The rise of social media and online commerce has also changed the way that Halloween candy is marketed and consumed. Candy companies now engage in elaborate digital campaigns, partnering with influencers and creating viral content to generate buzz and sales. The internet has also created new opportunities for niche and specialty candy makers to reach a wider audience, bypassing traditional retail channels.

Despite these shifts and challenges, the Halloween candy industry shows no signs of slowing down. In 2019, Americans spent a record $2.6 billion on Halloween candy, and the holiday continues to grow in popularity around the world. As long as there are children (and adults) with a sweet tooth and a love of dressing up, Halloween candy will remain a cherished and essential part of the celebration.

0 Comments