The Million-Dollar Math Nobody Talks About

When Joel Blackstock worked on an assertive community treatment team in Alabama, he discovered something remarkable: for every chronically homeless person with severe mental illness that his 13-person team helped, they saved the state Medicaid system one million dollars. Yet politicians still wanted to cut the program. This paradox lies at the heart of American healthcare policy – and it’s costing all of us.

In a revealing conversation with healthcare policy expert Timothy Faust on the Discover Heal Grow podcast, we learn why the economics of healthcare are completely backwards from what most people believe. The truth? Cutting healthcare spending doesn’t save money – it costs everyone more in the long run.

The Accidental System: How We Got Here

America’s healthcare system wasn’t designed – it evolved through historical accidents. As Faust explains, during World War II, wage freezes forced employers to offer health insurance as a perk to attract workers. This temporary solution became the backbone of how a third of Americans get their insurance today.

“The way we run healthcare in America is not a way you would design healthcare to be run if you had any say in the matter,” Faust notes. It’s a patchwork of one-off agreements and policy Band-Aids that created what he calls a “byzantine, hard to follow model.”

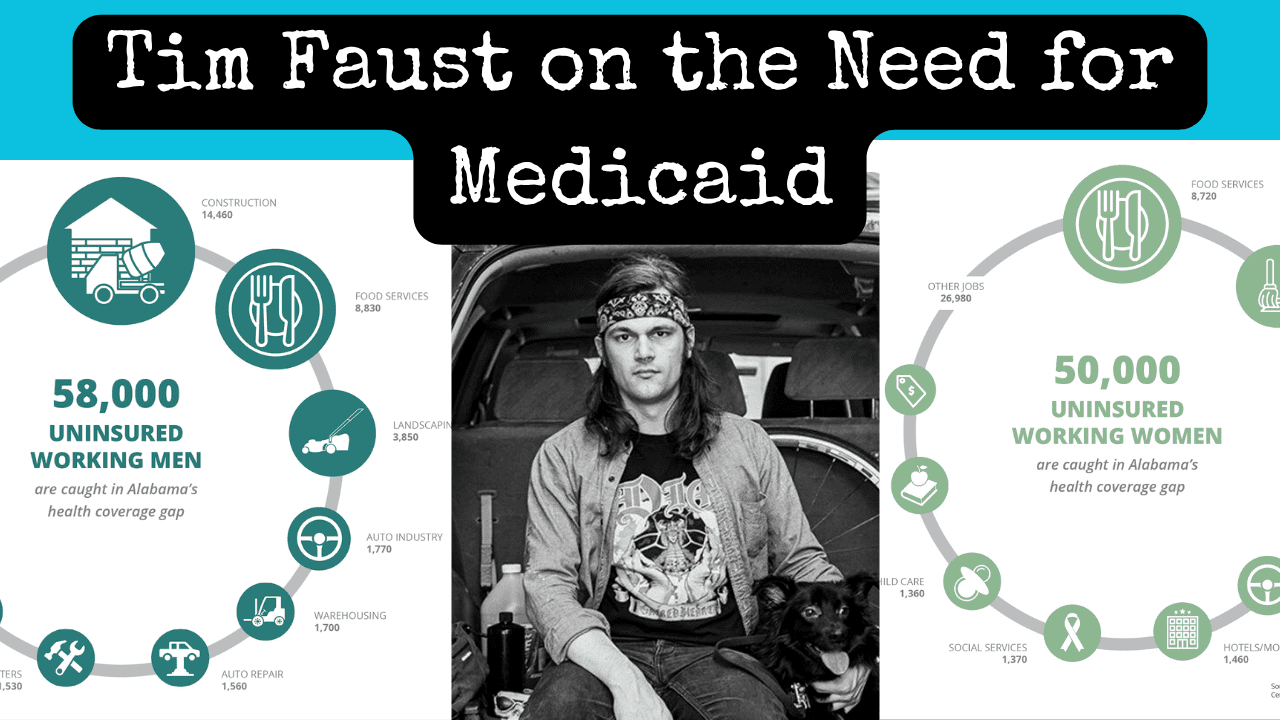

The Business Case for Medicaid Expansion

Contrary to political rhetoric, Medicaid expansion makes financial sense. States that didn’t expand Medicaid experienced four times higher rates of rural hospital closures than expansion states. Why? Because Medicaid is often the only payer willing to fund healthcare in areas where it’s not profitable.

The economic realities are stark. It’s simply not profitable to build hospitals in rural areas with low population density, yet these communities desperately need healthcare access. When it comes to preventative care, treating diabetes early costs hundreds of dollars, while treating diabetic complications can cost hundreds of thousands. Meanwhile, uninsured patients using emergency rooms for primary care drives up costs for everyone in the system. Perhaps most importantly, every dollar spent on healthcare creates four dollars of economic activity, making it one of the best investments a state can make.

Real Stories, Real Impact

Faust shares his own story of how Medicaid saved his life – and his economic future. At 23, making $14,000 a year working three jobs, he ignored a persistent cough because he couldn’t afford healthcare. It turned into double pneumonia, landing him in the ER with a $10,000+ bill that would have destroyed his life. California’s Medicaid expansion reduced that bill to zero.

“The only reason I have the life that I have – a wife I love, work that’s interesting to me – is because I wasn’t put under the burden of five-figure medical debt at a vulnerable point in my life,” he reflects.

The Hidden Costs of Means-Testing

One of the most counterproductive aspects of our system is the obsession with means-testing – making sure only the “deserving” poor get help. This creates perverse incentives that actually cost more than universal coverage would. Take the example of a cobbler with multiple sclerosis who can’t take on more clients because earning too much would disqualify him from Medicaid, and no private insurance will cover his MS treatments affordably. He’s forced to work less to stay alive.

The bureaucratic waste is staggering. One disabled man Faust describes receives monthly visits from a nurse to verify he’s still disabled from his degenerative condition – an expensive way to check if a miracle has occurred. The administrative burden is so complex that the application process prevents eligible people from getting coverage, sometimes requiring what Faust calls “teams of social workers with lawyers” in some states just to navigate the paperwork.

Why Healthcare Isn’t a Market

Politicians often invoke “market solutions” for healthcare, but as the discussion reveals, healthcare fundamentally lacks basic market features. First, there’s no real price transparency. The same MRI machine in the same location can have a five-fold price variance depending on which insurer is paying, which doctor is involved, and even what day of the week it is. This isn’t how markets work.

Second, you have no real choice when you need healthcare. As Blackstock points out, you can’t shop around while having a heart attack in an ambulance. You go where they take you and pay whatever they charge. Third, you’re a captive audience because the alternative to buying healthcare is often death or permanent disability – not a real market choice. Finally, there’s massive information asymmetry. Sick people lack the capacity to navigate complex pricing while dealing with illness. As Faust notes, “the sicker you are, the less capacity you have to navigate all this paperwork and do all this shopping around.”

The Economic Engine Nobody Sees

Here’s what politicians don’t tell you: healthcare spending drives local economies in ways that other government spending simply doesn’t. In Wisconsin, home health workers are the most common job, entirely funded by Medicaid. Healthcare facilities are often the largest employers in both urban and rural areas. When you fund Medicaid, you’re creating skilled jobs in rural areas where employment opportunities are scarce. You’re keeping money circulating in local economies instead of sending it to distant corporate headquarters. You’re preventing medical bankruptcies that destroy consumer spending power. And you’re maintaining the workforce by keeping people healthy enough to work.

The contrast with other types of government spending is stark. As Faust explains, every dollar spent on healthcare creates four dollars of economic activity through salaries that get spent on rent, food, and local services. Meanwhile, every dollar spent on defense or military contracts creates less than one dollar of economic activity. “If you were optimizing your spending to make the most money long term, you’d put it all in healthcare,” Faust notes.

The Insurance Industry’s Dirty Secret

The conversation reveals how the current system creates a “war” between hospitals trying to charge as much as possible and insurers trying to pay as little as possible. Both sides employ “tens of thousands if not hundreds of thousands of people” just to fight over billing. Meanwhile, both industries profit while patients get stuck with the bills.

The perverse part? Insurance companies make more money when healthcare costs more – they just pass higher premiums to consumers. There’s no incentive to actually control costs.

What Actually Works: Evidence from Other Countries

Every other developed nation has figured this out: you need a central authority to regulate healthcare prices. Whether through single-payer systems or tightly regulated markets, successful countries share one common feature. They have someone in the middle saying “this is what healthcare actually costs, and that’s what we’ll pay.” This prevents the pricing chaos we see in America.

The U.S. delegates this crucial function to thousands of insurance companies that are, as Faust puts it, “both incapable because they’re too small and unwilling because they get paid more” to control costs. Every other country, even those with market-based solutions, has this central price setter. We’re the only developed nation that lets healthcare prices run wild with no oversight, and we pay the price in both dollars and lives.

The Path Forward: Bipartisan Solutions

Despite the polarization, there are popular solutions that could work across party lines. The most obvious is allowing Medicare to use its bulk purchasing power to negotiate drug prices like every other large purchaser in the world. Currently, we have the absurd situation where taxpayers fund drug development, then private companies own the patents and charge whatever they want, and then Medicare is legally prohibited from negotiating lower prices.

Simplifying administration could save billions. Right now, we have armies of billing specialists on both the hospital and insurance sides fighting over every line item. This administrative warfare adds nothing to patient care but drives up costs for everyone. Providing universal basic coverage would give everyone a floor they can count on, reducing emergency room visits and allowing people to get preventative care. And implementing reasonable price regulation based on actual costs of care, like every other developed nation does, would end the pricing free-for-all that enriches middlemen while bankrupting patients.

The Real Cost of Inaction

When we don’t fund preventative care, the consequences ripple through our entire economy and society. Treatable conditions become expensive emergencies that could have been prevented with basic medication or lifestyle interventions. A diabetic who can’t afford insulin ends up in the ICU with ketoacidosis, costing hundreds of thousands instead of hundreds. Medical debt destroys economic mobility, keeping talented people trapped in dead-end jobs because they can’t risk losing insurance or can’t qualify for educational loans.

Rural hospitals close when Medicaid funding disappears, forcing people to drive hours for basic care. This doesn’t just inconvenience rural residents – it overloads urban hospitals and makes care worse for everyone. Emergency rooms overflow with primary care cases because people have nowhere else to go, making real emergencies wait longer and driving up costs through the least efficient form of care delivery. Young, talented people who could contribute enormously to our economy can’t pursue education or start businesses because they’re drowning in medical debt from a illness or accident that wasn’t their fault.

It’s Not About Ideology – It’s About Math

The evidence is clear: Medicaid expansion saves money. Not in some abstract, long-term way, but in real, measurable dollars. When Alabama’s assertive community treatment team saves $1 million per patient per year, that’s not liberal talking points – that’s conservative fiscal policy.

As Faust concludes, “Pay for healthcare now, save money down the road. And more than that, people can have longer and better lives, which is good for all of us.”

The question isn’t whether we can afford to expand healthcare access. The question is whether we can afford not to.

For more insights on healthcare policy and economics, subscribe to Timothy Faust’s newsletter at buttondown.com/error and check out the Discover Heal Grow podcast from Taproot Therapy Collective

0 Comments