A History of the Mummy:

Mummies have long held a place of fascination in the human imagination, serving as enduring symbols of ancient civilizations and the mysteries of life and death. From the carefully preserved remains of ancient Egyptian pharaohs to the naturally mummified bodies discovered in bogs and glaciers, mummies provide a tantalizing glimpse into the past and offer insights into the beliefs, practices, and cultural values of the societies that created them (Aufderheide, 2003). By examining mummies through the lenses of history, anthropology, and cultural studies, we can gain a deeper understanding of their significance and the roles they have played in shaping our perceptions of mortality, spirituality, and the afterlife.

The Mummy in Popular Culture: Fascination and Fear

The mummy has also had a significant impact on popular culture, serving as a source of both fascination and fear. The discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 sparked a global interest in ancient Egypt and mummies, leading to a proliferation of mummy-themed media, including books, films, and exhibitions (Day, 2006).

In literature and film, the mummy has often been portrayed as a terrifying, supernatural creature, rising from the dead to seek revenge or to reclaim lost love (Luckhurst, 2012). Works such as Bram Stoker’s “The Jewel of Seven Stars” (1903) and the Universal Studios film “The Mummy” (1932) have helped to establish the mummy as a classic horror icon, alongside vampires, werewolves, and other monsters (Cowie, 1989).

However, the popularization of the mummy in media has also led to the perpetuation of stereotypes and misconceptions about ancient Egyptian culture and the practice of mummification (Lant, 1992). The portrayal of mummies as mindless, shambling monsters has often overshadowed the rich history and cultural significance of these ancient remains, leading to a simplification and sensationalization of their true nature (Montserrat, 1997).

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in presenting mummies in a more accurate and respectful manner, with museums and researchers working to educate the public about the cultural and historical context of these remains (Foster, 2001). By promoting a more nuanced understanding of mummies and their significance, we can begin to appreciate these ancient individuals as a testament to the enduring human desire to preserve life and legacy beyond death.

The Egyptian Mummy: Preservation for the Afterlife

The ancient Egyptians are perhaps best known for their elaborate mummification practices, which were closely tied to their religious beliefs and their understanding of the afterlife. For the Egyptians, the preservation of the physical body was essential for the soul’s survival in the afterlife (Ikram, 2003). The mummification process, which involved removing internal organs, treating the body with natron (a natural salt), and wrapping it in linen bandages, was believed to transform the deceased into a sacred being, an “Osiris,” who would journey through the underworld and be reborn into eternal life (Dodson & Ikram, 2008).

The mummification of Egyptian royalty and nobility was a highly ritualized and symbolic process, with each step imbued with religious significance (Buckley & Evershed, 2001). The use of amulets, inscribed bandages, and elaborate sarcophagi served to protect and guide the deceased on their journey to the afterlife, while the inclusion of grave goods, such as food, clothing, and personal possessions, ensured that the deceased would have all the necessities for their eternal existence (Taylor, 2010).

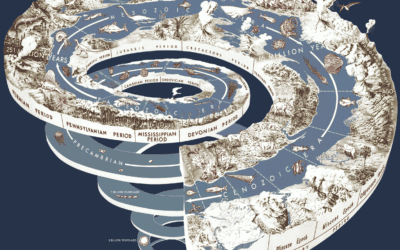

The Egyptian mummy serves as a powerful symbol of the culture’s preoccupation with death and the afterlife, as well as its belief in the cyclical nature of existence (Assmann, 2005). The preservation of the physical body was not only a means of ensuring the soul’s survival but also a way of maintaining a connection between the living and the dead, as evidenced by the practice of ancestor worship and the use of mummies in religious ceremonies (Bommas, 2011).

Mummies in the Americas: Andean and Mesoamerican

Traditions Mummification practices were not limited to ancient Egypt; they were also prevalent in various cultures throughout the Americas. In the Andean regions of South America, the Chinchorro people began mummifying their dead as early as 7000 BCE, predating Egyptian mummification by several millennia (Arriaza, 1995). Chinchorro mummies were created through a complex process that involved defleshing the body, reinforcing the skeleton with sticks and reeds, and covering the remains with clay and paint to recreate the appearance of the deceased (Aufderheide et al., 1993).

In Mesoamerica, the Maya and Aztec cultures also practiced mummification, although their methods differed from those of the ancient Egyptians. Mayan mummies were typically created through a process of smoking and drying the body, while Aztec mummies were often preserved through a combination of desiccation and embalming with resins and aromatics (Tiesler & Cucina, 2006).

Like the Egyptians, the Andean and Mesoamerican cultures associated mummification with religious beliefs and the afterlife. Mummies were often buried with grave goods and offerings, and in some cases, they were believed to possess supernatural powers and were used in religious ceremonies and rituals (Benson & Cook, 2001). The preservation of the physical body was seen as a means of ensuring the continuity of the individual’s essence and their connection to the living community (Fitzsimmons, 2009).

Natural Mummies: Bog Bodies and Glacier Mummies

In addition to intentional mummification practices, there are also numerous examples of naturally preserved mummies found in bogs, glaciers, and other environments that inhibit decomposition. These mummies, often discovered by chance, provide a unique window into the lives and deaths of individuals from different time periods and cultures.

Bog bodies, which are mummies that have been naturally preserved in the acidic, oxygen-poor environments of peat bogs, have been discovered throughout Northern Europe, with notable examples including the Tollund Man and the Grauballe Man from Denmark (Sanders, 2009). These mummies often exhibit remarkable preservation, with skin, hair, and internal organs intact, allowing researchers to study their physical characteristics, diet, and health (Brothwell & Gill-Robinson, 2002).

Similarly, glacier mummies, such as the famous Ötzi the Iceman discovered in the Ötztal Alps on the border between Austria and Italy, provide valuable insights into the lives of ancient peoples (Spindler, 1994). Ötzi, who lived around 3300 BCE, was found with a wealth of artifacts, including clothing, tools, and weapons, which have helped researchers reconstruct aspects of his life and the culture in which he lived (Fowler, 2000).

The study of natural mummies has also shed light on the circumstances surrounding their deaths, with many bog bodies exhibiting signs of violent trauma, suggesting that they may have been victims of ritual sacrifice or execution (Glob, 1969). These mummies serve as a testament to the complex relationships between life, death, and society in ancient cultures, and they continue to captivate the public imagination and inspire new research and discoveries.

Symbolism of the Mummy

he mummy, in its various forms and cultural contexts, serves as a powerful symbol of the human fascination with death, immortality, and the afterlife. From the meticulously prepared remains of ancient Egyptian royalty to the naturally preserved bodies discovered in bogs and glaciers, mummies offer a unique glimpse into the lives, beliefs, and practices of past societies.

By examining mummies through the lenses of history, anthropology, and cultural studies, we can gain a deeper appreciation for their significance and the enduring impact they have had on our understanding of life, death, and the human experience. As we continue to study and learn from these ancient remains, we are reminded of the shared human desire to transcend mortality and to leave a lasting legacy for future generations.

Bibliography

Arriaza, B. T. (1995). Beyond death: The Chinchorro mummies of ancient Chile. Smithsonian Institution Press. Assmann, J. (2005). Death and salvation in ancient Egypt. Cornell University Press. Aufderheide, A. C. (2003). The scientific study of mummies. Cambridge University Press. Aufderheide, A. C., Muñoz, I., & Arriaza, B. (1993). Seven Chinchorro mummies and the prehistory of northern Chile. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 91(2), 189-201. Benson, E. P., & Cook, A. G. (Eds.). (2001). Ritual sacrifice in ancient Peru. University of Texas Press. Bommas, M. (2011). Mummies, magic and medicine in ancient Egypt. Manchester University Press. Brothwell, D., & Gill-Robinson, H. (2002). Taphonomic and forensic aspects of bog bodies. In V. H. Spence, W. D. Haglund, & M. J. Sorg (Eds.), Advances in forensic taphonomy: Method, theory, and archaeological perspectives (pp. 119-132). CRC Press. Buckley, S. A., & Evershed, R. P. (2001). Organic chemistry of embalming agents in Pharaonic and Graeco-Roman mummies. Nature, 413(6858), 837-841. Cowie, S. D. (1989). The mummy in fact, fiction and film. McFarland & Company. Day, J. (2006). The mummy’s curse: Mummymania in the English-speaking world. Routledge. Dodson, A., & Ikram, S. (2008). The tomb in ancient Egypt: Royal and private sepulchres from the early dynastic period to the Romans. Thames & Hudson. Fitzsimmons, J. L. (2009). Death and the classic Maya kings. University of Texas Press. Foster, G. M. (2001). The mummy in the museum: Displaying human remains in the wake of NAGPRA. Journal of Museum Education, 26(3), 10-14. Fowler, B. (2000). Iceman: Uncovering the life and times of a prehistoric man found in an alpine glacier. University of Chicago Press. Glob, P. V. (1969). The bog people: Iron-age man preserved (R. Bruce-Mitford, Trans.). Cornell University Press. Ikram, S. (Ed.). (2003). Death and burial in ancient Egypt. Longman. Lant, A. (1992). The curse of the pharaoh, or how cinema contracted Egyptomania. October, 59, 86-112. Luckhurst, R. (2012). The mummy’s curse: The true history of a dark fantasy. Oxford University Press. Montserrat, D. (1997). Unidentified human remains: Mummies and the erotics of biography. In D. Montserrat (Ed.), Changing bodies, changing meanings: Studies on the human body in antiquity (pp. 168-197). Routledge. Sanders, K. (2009). Bodies in the bog and the archaeological imagination. University of Chicago Press. Spindler, K. (1994). The man in the ice: The discovery of a 5,000-year-old body reveals the secrets of the Stone Age. Harmony Books. Taylor, J. H. (2010). Egyptian mummies. British Museum Press. Tiesler, V., & Cucina, A. (Eds.). (2006). Janaab’ Pakal of Palenque: Reconstructing the life and death of a Maya ruler. University of Arizona Press

0 Comments