The Burden of Elevation: Understanding Alabama’s Most Aspirational Suburb

Perched atop Shades Mountain, Vestavia Hills, Alabama represents one of the most fascinating case studies in American suburban psychology—a community whose very identity was architected through deliberate psychological engineering, maintained through political exclusion, and now grapples with the mental health consequences of its own success. This is the story of how geography became destiny, how Roman temples became suburban ideology, and how the pursuit of “A Life Above” created both extraordinary prosperity and profound internal pressures.

To understand Vestavia Hills is to understand the fundamental American suburban paradox: the simultaneous desire for sanctuary and status, for community and exclusivity, for achievement and peace. But here, these tensions have been crystallized with unusual clarity, creating a municipality that functions as both Birmingham’s crown jewel and its most psychologically complex offspring.

Part I: The Material Foundations of Psychological Aspiration

The Geography of Superiority

The psychological story of Vestavia Hills begins not with human intention but with geological accident. The community sits atop Shades Mountain, part of the Ridge-and-Valley province of the Appalachian Mountains, physically elevated above the Birmingham valley below. This elevation—this literal high ground—would become the immutable material foundation for everything that followed.

The psychological story of Vestavia Hills begins not with human intention but with geological accident. The community sits atop Shades Mountain, part of the Ridge-and-Valley province of the Appalachian Mountains, physically elevated above the Birmingham valley below. This elevation—this literal high ground—would become the immutable material foundation for everything that followed.

Below this mountain ridge lay the source of Birmingham’s industrial might: the Red Mountain Formation with its rust-stained rocks and seams of hematite iron ore. When combined with the nearby Cahaba Coal Fields, this geological coincidence provided all three essential ingredients for steel production—iron ore, coal, and limestone. The Oxmoor Furnace, established in 1863 near what would become Vestavia Hills, represented the material engine that would generate the wealth necessary for the mountain’s eventual transformation into an elite refuge.

Yet this industrial foundation created a fundamental psychological tension that would define Vestavia Hills: the community’s existence depended entirely on the gritty industrial complex below, even as its identity would be constructed in explicit opposition to that industrial character. This dynamic—what we might call “aspirational disassociation”—became the community’s founding psychological principle.

The Indigenous Erasure and Hidden Histories

Before examining how Vestavia Hills constructed its identity, we must acknowledge what was erased to make that construction possible. For thousands of years, the land was inhabited by Creek, Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw peoples who utilized Shades Creek and the surrounding forests. Following the Creek Session of 1814, these populations were forcibly removed, though some, like the Echota Cherokee, survived by hiding in the mountains and deliberately concealing their ancestry—claiming to be “Black Dutch” to avoid the Trail of Tears.

This act of survival through cultural concealment stands in profound psychological contrast to what would come next: the highly visible, deliberately imported European symbolism that would define Vestavia Hills. Where indigenous peoples survived by hiding their identity, the new settlers would build their entire community around the conspicuous display of borrowed classical culture.

Part II: George Ward and the Architecture of Aspiration (1920-1945)

The Temple on the Mountain

The transformation of Shades Mountain from geographic feature to psychological landscape began with one man’s peculiar vision. George Ward, former Birmingham mayor and self-described “idealist, naturalist and lover of the classics,” didn’t merely build a house on the mountain—he constructed an entire mythological framework that would outlive him by a century.

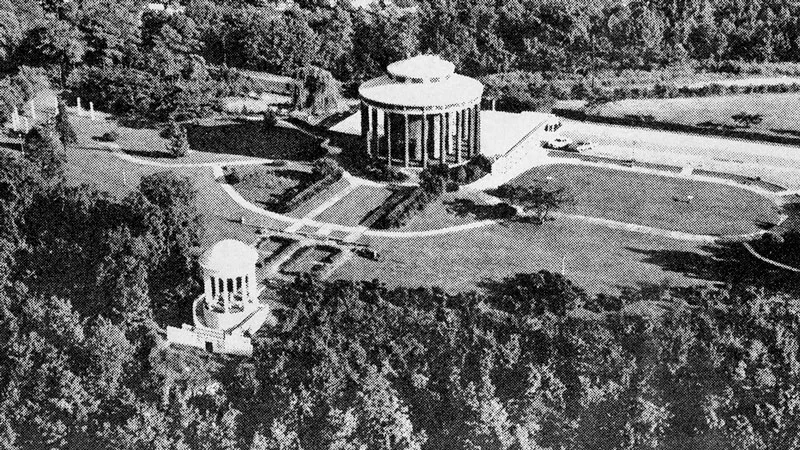

In 1925, Ward completed his mansion modeled after the Temple of Vesta in Rome, a circular structure of pink sandstone surrounded by twenty massive Doric columns. The name “Vestavia”—combining Vesta, the Roman goddess of hearth and home, with “via,” meaning by the roadway—wasn’t merely pretentious nomenclature. It was psychological programming.

Consider what Vesta represented in Roman culture: the sacred flame that must never be extinguished, tended by the Vestal Virgins who faced burial alive if they lost their chastity. Ward was importing not just architectural aesthetics but an entire value system centered on purity, domestic sanctity, and severe consequences for transgression. This symbolism would prove remarkably durable, embedding itself so deeply in the community’s psyche that the Sibyl Temple—Ward’s garden gazebo modeled after the Temple of Sibyl at Tivoli—remains on the city seal today, decades after the main house was demolished.

The Magnetic Pull of Idealization

Ward’s classical folly might have remained merely eccentric had it not tapped into a deeper psychological need among Birmingham’s emerging professional class. The industrial city below was generating wealth but also soot, noise, and social disorder. The mountain offered not just cleaner air but psychological elevation—a place where success could be translated into refinement, where new money could acquire old-world gravitas.

Early residents like Louis Pizitz, owner of the Pizitz Department Store, who built his home “Happy Dale” in 1931, weren’t just buying property—they were buying into a narrative. The establishment of Shades Mountain Baptist Church (originally Miller Chapel, circa 1926) provided the necessary institutional anchor for this emerging community of aspiration.

Part III: The Politics of Exclusion and the Birth of a City (1946-1980)

Suburbanization as Psychological Project

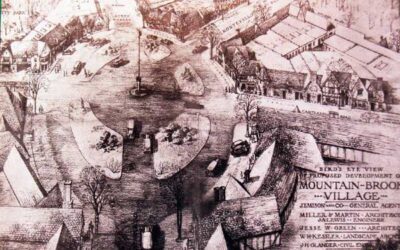

The post-World War II era transformed Ward’s elite sanctuary into a mass suburban phenomenon, but the psychological framework remained intact. Developer Charles Byrd’s 1946 subdivision plan for 1,000 residents on Shades Mountain’s southern slopes wasn’t selling houses—it was selling a lifestyle, an identity, a psychological position vis-à-vis the city below.

The incorporation of Vestavia Hills on November 8, 1950 represented the first formal political expression of this psychological imperative. By choosing a Council-Manager form of government, the new city prioritized professional administration over democratic messiness—a choice that reflected its residents’ preference for predictability and control.

The Great Secession: Schools as Psychological Fortification

No single decision more powerfully demonstrates Vestavia Hills‘ core psychological dynamics than the creation of Vestavia Hills City Schools in 1970. This wasn’t merely administrative restructuring—it was an act of secession from the Jefferson County school system that must be understood within the context of resistance to racial integration.

Historical analysis, including research from scholars at UTC and reporting from Liberation News, confirms that the formation of these “Over the Mountain” school districts was fundamentally motivated by a desire to maintain racial and socioeconomic homogeneity. The Vestavia Hills High School mascot was, until recently, “The Rebel,” complete with Confederate imagery—a symbol that made the psychological motivations explicit.

Yet this act of exclusion created a paradox that defines the community to this day. By taking control of their schools, Vestavia Hills guaranteed educational excellence, which drove property values, which funded better schools, which attracted more affluent families—a virtuous cycle for those inside, a vicious barrier for those outside. The school system became both the community’s greatest asset and its most effective mechanism of exclusion.

The Republican Realignment

The school secession aligned with a broader psychological and political shift documented in Mississippi State University research: the emergence of suburban Birmingham as a Republican stronghold. This wasn’t merely party preference but a complete worldview centered on local control, low taxes, and resistance to federal intervention—values that mapped perfectly onto the community’s founding psychology of autonomy and exclusivity.

Part IV: Expansion and the Economics of Aspiration (1980-Present)

The Annexation Imperative

The opening of the Red Mountain Expressway in 1977 triggered explosive growth, nearly doubling Vestavia Hills’ population to 15,729 by 1980. But growth brought a new challenge: how to maintain exclusivity while expanding? The answer lay in Alabama’s “lasso laws,” which allowed cities to annex non-contiguous territory through thin connecting strips.

The annexations of Rocky Ridge, Altadena, Liberty Park, and especially Cahaba Heights in 2002 weren’t just geographic expansion—they were resource capture. As documented in the city’s budget reports, sales and use taxes generate $29.6 million annually, surpassing property taxes ($20.9 million). The annexation of commercial areas was essential to funding the high-cost school system that justified the community’s premium property values.

The legal challenges to these annexations, particularly from Birmingham, revealed the zero-sum nature of municipal competition in metropolitan areas. Every wealthy neighborhood Vestavia Hills annexed was a loss for Birmingham’s tax base—a material transfer that reinforced psychological and racial divisions.

The Formalization of Aspiration

In 2014, Vestavia Hills adopted the motto “A Life Above,” making explicit what had always been implicit. The official values—”Unity, Prosperity, Family”—directly echo the Vestal symbolism Ward introduced ninety years earlier. This wasn’t coincidence but continuity, a multigenerational commitment to a particular vision of community.

The Library in the Forest, Alabama’s first LEED gold-certified library, exemplifies this vision materialized. It’s not enough to have a library; it must be architecturally distinguished, environmentally progressive, literally and figuratively elevated. Every infrastructure investment, from the Aquatic Complex at Wald Park to the Altadena Valley Park development, reinforces the brand promise of exceptional quality.

Part V: The Psychological Cost of Paradise

The Achievement Trap

Today, Vestavia Hills has achieved everything its founders envisioned. The median household income of $127,582 far exceeds state and national averages. The school system produces extraordinary outcomes, with high numbers of National Merit Scholars and millions in college scholarships annually. Property values continue to climb, with median home prices reaching $494,500.

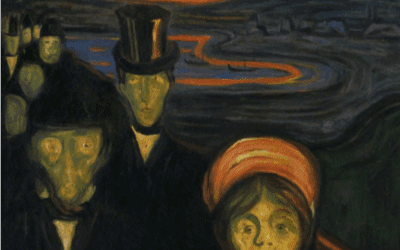

Yet this success has created what researchers identify as a mental health crisis among “high achieving schools”—environments where youth face pressures comparable to those in poverty. The psychological forces that created Vestavia Hills’ success—competition, perfectionism, constant comparison—now manifest as epidemic levels of anxiety and depression among its youth.

Local mental health professionals report treating anxiety in 96% of their clients, depression in 91%, and chronic stress in 78%. The high concentration of over 100 therapists in a city of 40,000 represents both a response to this crisis and, paradoxically, a privilege—the community’s wealth means most families can afford the help they need.

The Impostor Syndrome of Success

Research on high achievers reveals a particular psychological pattern that seems to define much of Vestavia Hills’ internal experience: the “High Achiever’s Dilemma”. Despite external validation and material success, many residents report:

- Chronic feelings of inadequacy

- Intense fear of failure that paradoxically inhibits risk-taking

- Difficulty enjoying achievements, immediately moving to the next goal

- A sense that their success is fraudulent or undeserved

This impostor syndrome operates at both individual and collective levels. Just as individual residents question whether they truly deserve their success, the community itself seems haunted by the question of whether its prosperity is legitimate or built on exclusion.

The School System’s Response

Vestavia Hills City Schools has acknowledged these pressures, implementing comprehensive mental health programs including suicide prevention initiatives. But these programs face a fundamental contradiction: they’re trying to treat symptoms created by the very excellence the system is designed to produce.

The pressure begins early, with elementary students aware they’re being prepared for a competitive high school experience that will determine college admissions, which will determine career success, which will determine whether they can afford to raise their own children in Vestavia Hills. The cycle is both self-perpetuating and self-consuming.

Part VI: The Workforce and the Performance of Prosperity

The Professional Imperative

With 60.1% of residents active in the civilian labor force and an average commute of just 19.8 minutes, Vestavia Hills functions as a bedroom community for Birmingham’s professional class. Major employers include Vulcan Materials, Naphcare, and various healthcare systems—predominantly white-collar environments that demand sustained high performance.

The relationship between work and identity in Vestavia Hills is particularly intense. Professional success isn’t just about income—it’s about maintaining the family’s position in the community hierarchy. Job loss or career setback threatens not just financial security but social standing and even residential stability, given the high cost of living.

Integration and Recovery

The Alabama Department of Mental Health’s focus on Individual Placement and Support (IPS) for people with serious mental illness presents an interesting challenge for communities like Vestavia Hills. The IPS model emphasizes competitive employment based on client preferences—but in an environment where “competitive” is the baseline expectation, the barriers to entry and sustained success are extraordinarily high.

This creates a hidden population within Vestavia Hills: those struggling with mental health issues who must perform wellness to maintain their position in the community. The very resources that should support recovery—the high concentration of mental health services—can become another performance metric, another thing to optimize.

Part VII: The Material-Psychological Synthesis

The Feedback Loop of Place

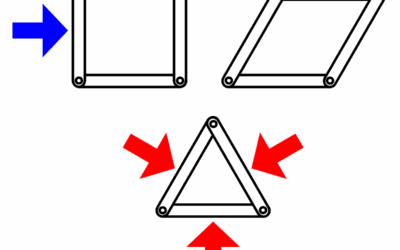

Vestavia Hills demonstrates how physical geography, political economy, and collective psychology can synthesize into a self-reinforcing system. The mountain location provided the initial differentiation from Birmingham. George Ward’s classical imagery provided the mythological framework. The school secession provided the mechanism of exclusion. The annexations provided the tax base. The “Life Above” branding provided the narrative coherence.

Each element reinforces the others. High property values fund excellent schools, which attract affluent families, who demand excellent schools, which require high property values to fund. The psychological pressure to maintain this cycle becomes immense, affecting everything from local politics to individual therapy sessions.

The Paradox of Sanctuary

George Ward envisioned Vestavia Hills as a sanctuary—a place of peace and refinement above the industrial tumult. In many ways, he succeeded beyond imagination. Yet the sanctuary has become a pressure cooker, where the very qualities that make it desirable—excellence, exclusivity, achievement—create their own forms of stress and suffering.

The community finds itself trapped in what we might call the “sanctuary paradox”: the harder it works to maintain its elevated status, the less it resembles the peaceful refuge it was meant to be. The classical columns remain, but the psychological architecture they represent—the pursuit of an idealized domestic perfection—has become a source of anxiety rather than comfort.

Part VIII: Contemporary Vestavia Hills and Future Trajectories

The Sustainability Question

As Vestavia Hills approaches its 75th anniversary as an incorporated city, fundamental questions about sustainability emerge—not environmental sustainability (though the LEED-certified library suggests some awareness of this issue), but psychological and social sustainability.

Can a community built on exclusion evolve toward greater inclusion without losing its identity? Can it maintain educational excellence without destroying its children’s mental health? Can it preserve its “Life Above” while acknowledging the moral complexity of that elevation?

The city’s comprehensive planning documents, including the Vestavia Hills Comprehensive Master Plan and various village plans, suggest awareness of these challenges. There’s discussion of diversity, sustainability, and community wellness. Yet these documents also reveal the fundamental conservation at the city’s core—the desire to preserve what has been achieved rather than fundamentally reimagine what could be.

The Next Generation’s Dilemma

Perhaps the most poignant aspect of contemporary Vestavia Hills is the experience of its youth. Raised in material comfort but psychological pressure, academically accomplished but emotionally strained, they embody the community’s contradictions most acutely.

Many young adults who grew up in Vestavia Hills report a complex relationship with their hometown. They’re grateful for the education and opportunities it provided, yet exhausted by the pressure it imposed. They want to raise their own children with those advantages, yet fear replicating the stress they experienced. They love the community’s beauty and resources, yet feel suffocated by its expectations.

This generational ambivalence may ultimately force the evolution that political and economic forces have not. As mental health awareness increases and the costs of perfectionism become undeniable, the next generation may demand a different version of the “Life Above”—one that elevates wellbeing over achievement, community over competition, authenticity over aspiration.

Conclusion: The American Dream as Psychological Experiment

Vestavia Hills represents more than just another wealthy suburb. It’s a seventy-year psychological experiment in American aspiration, a community that has pursued a particular vision of the good life with unusual clarity and consistency. The results of this experiment are both impressive and troubling, offering lessons for other communities grappling with similar tensions.

The success is undeniable: excellent schools, beautiful homes, extensive amenities, engaged citizens. By almost any material measure, Vestavia Hills has achieved the American Dream. Yet the psychological data—the therapy statistics, the student stress levels, the pervasive anxiety—suggest that this dream may be more nightmare than paradise for many who live it.

The story of Vestavia Hills ultimately asks us to consider what we’re optimizing for when we build communities. If the goal is property values and test scores, Vestavia Hills is a tremendous success. If the goal is human flourishing and psychological wellbeing, the record is far more complex. The temple on the mountain still stands, but the question remains: what gods are we really serving, and at what cost?

Perhaps the most profound insight from Vestavia Hills’ psychological trajectory is this: a community’s greatest strength can become its greatest vulnerability. The very forces that create excellence can destroy wellbeing. The walls that preserve prosperity can become prisons. The aspiration to live “above” can leave residents feeling perpetually beneath their own expectations.

As American suburbs everywhere grapple with questions of identity, inclusion, and mental health, Vestavia Hills offers both a cautionary tale and a hopeful possibility. Its resources, self-awareness, and institutional capacity position it to potentially pioneer new models of suburban life that maintain excellence without sacrificing wellness. Whether it will embrace this opportunity or remain trapped in its own beautiful sanctuary remains to be seen.

The view from Shades Mountain is indeed spectacular. The question for Vestavia Hills’ future is whether its residents can find a way to enjoy that view without the vertigo that comes from constantly fearing the fall.

0 Comments