Washington D.C.’s Sacred Geometry and the Revolutionary Transformation of Divine Authority

A Capital Born from Enlightenment

When Pierre Charles L’Enfant stood upon Jenkins Hill in March 1791, surveying the wilderness that would become America’s capital, he carried with him not just architectural plans but revolutionary ideas about power, authority, and the divine right to rule. The city he would design—though never fully realized according to his vision—would become a physical manifestation of humanity’s most profound philosophical transformation: the shift from feudal divine right based on land ownership to Enlightenment ideals of merit, reason, and the consent of the governed.

The Unpopular Visionary and His Patron

L’Enfant was, by many accounts, a difficult man. George Washington famously demurred when offered a royal title, preferring instead the more republican title of President, yet he saw something in this temperamental French engineer that others missed. Despite L’Enfant’s reputation for being obstinate and his tendency to disregard instructions of the city commissioners who had authority to oversee his work, Washington entrusted him with designing the new nation’s capital.

The relationship between Washington and L’Enfant was complex. “Having the beauty and harmony of your plan only in view, you pursue it as if every person and thing was obliged to yield to it,” Washington wrote to him. Yet Washington persisted in supporting L’Enfant’s vision, understanding perhaps that creating a capital for a new form of government required someone who could think beyond conventional boundaries.

Sacred Geometry and Masonic Symbolism

L’Enfant’s design was far from arbitrary. As an art student in Paris and the son of an architect at Versailles, L’Enfant was versed in the ancient mathematical concepts of Pi, the Fibonacci Sequence, and Phi or the Golden Mean. These weren’t merely mathematical concepts but spiritual principles that the ancients believed revealed universal truths.

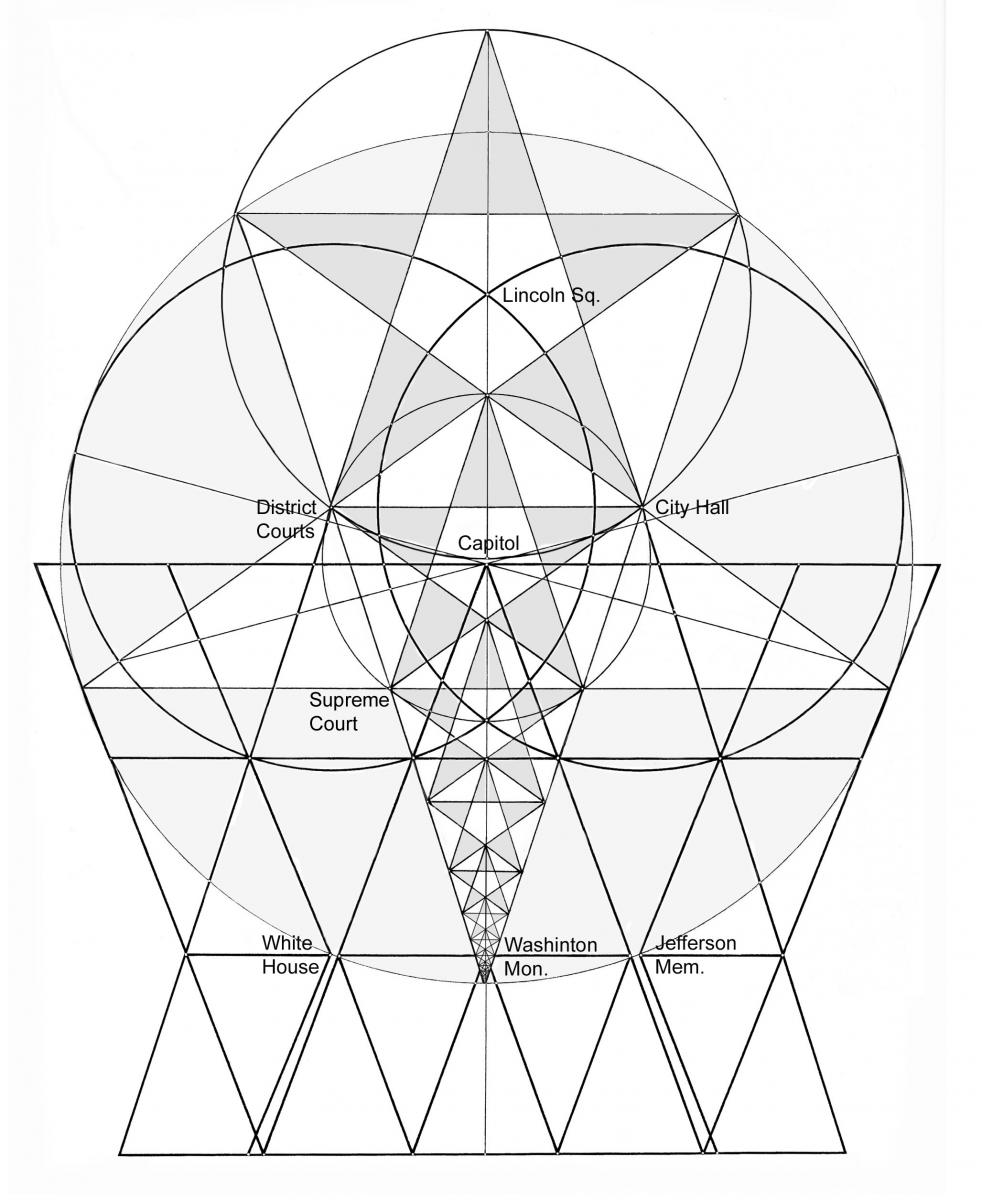

According to Nicholas R. Mann’s groundbreaking analysis in “The Sacred Geometry of Washington, D.C.,” L’Enfant incorporated these principles deliberately:

The Numbers of Heaven and Earth

The number 5, displayed in the stars expanding out from the Capitol, represented to the ancients the spiritual power of earth and its people. The number 6, represented by the two angled avenues extending out from the White House, held the spiritual power of the heavens and the gods. This wasn’t mere symbolism—it was an attempt to reconcile heavenly and earthly powers, the spiritual and democratic ideals, in the geometry itself.

The Golden Section

The city’s layout followed what Mann identifies as a Golden Section Template, which determined the locations of major buildings, public squares, and so forth. This same template would later unknowingly guide the placement of the Lincoln and Jefferson Memorials and even the Pentagon.

Masonic Influences

While George Washington was a Freemason, and Masons maintain that though their Lodges can be dated only from 1717, Freemasonry actually developed out of medieval builders’ guilds, the extent of Masonic influence on L’Enfant’s design remains debated. The obsession with geometrical forms to be found in the works of speculative Freemasonry is an echo of this tradition, though L’Enfant himself was initiated into Freemasonry only after arriving in America.

The Revolutionary Context: From Land to Enlightenment

To understand why Washington D.C.’s design was revolutionary, we must understand the system it was rejecting. The American Revolution wasn’t just about taxation—it was about the fundamental question of what gives someone the right to rule.

The Feudal System of Divine Right

In medieval Europe, The kings believed they were given the right to rule by God. This was called “divine right”. This system was intrinsically tied to land ownership. In broad terms a lord was a noble who held land, a vassal was a person granted possession of the land by the lord, and the land was known as a fief.

The divine right of kings wasn’t just a political theory—it was a comprehensive worldview. Divine right of kings, in European history, a political doctrine in defense of monarchical absolutism, which asserted that kings derived their authority from God and could not therefore be held accountable for their actions by any earthly authority such as a parliament.

The Colonial Challenge

In the American colonies, this system began to break down. From their first settlement, the English Provinces received impressions favourable to democratic forms of government. Their dependent situation forbad any inordinate ambition among their native sons. The colonists, removed from European aristocracy, were strongly impressed with an opinion, that all men are by nature equal. They could not easily be persuaded that their grants of land, or their civil rights, flowed from the munificence of Princes.

The abundance of land in America fundamentally challenged the European concept of divine right through land ownership. In consequence of the vast extent of vacant country, every colonist was, or easily might be, a freeholder. Settled on lands of his own, he was both farmer and landlord-producing all the necessaries of life from his own grounds, he felt himself both free and independent.

Jefferson, Washington, and the Enlightenment Vision

The Founding Fathers, steeped in Enlightenment philosophy, proposed a radical alternative. Both moderate and radical American Enlightenment thinkers, such as James Madison, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, John Adams and George Washington, were deists. They believed not in divine right through inherited land, but in what Jefferson would call natural rights.

He believed that God made all mankind originally equal: That he endowed them with the rights of life, property, and as much liberty as was consistent with the rights of others. This wasn’t just political philosophy—it was a complete reimagining of the source of legitimate authority.

L’Enfant’s Vision: Architecture as Philosophy

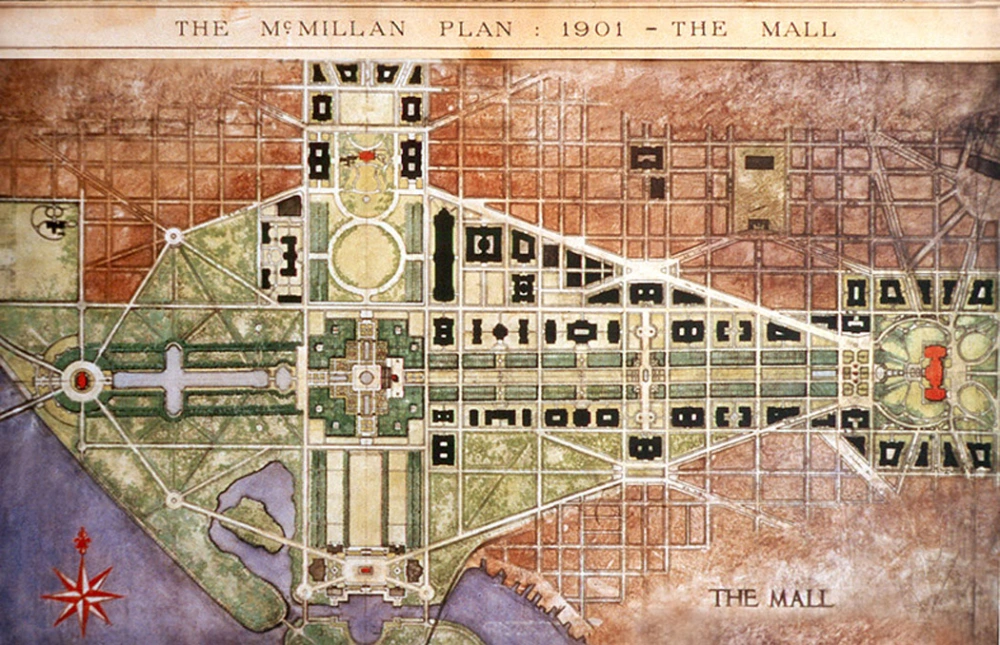

L’Enfant understood that the new capital needed to embody these revolutionary principles architecturally. L’Enfant placed Congress on a high point with a commanding view of the Potomac, instead of reserving the grandest spot for the leader’s palace as was customary in Europe. This was a radical departure from European capitals, where the monarch’s palace dominated the urban landscape.

The Mall: An Egalitarian Space

“The Mall was designed as open to all comers, which would have been unheard of in France. It’s a very sort of egalitarian idea”. In European cities, such grand spaces were reserved for aristocracy. L’Enfant’s Mall was a physical manifestation of the idea that in America, sovereignty resided in the people.

The Capitol as Center

In L’Enfant’s original design, the Capitol—not the President’s House—was the true center. L’Enfant used this to symbolize the citizens as represented in the Capital Building. The radiating avenues from the Capitol, named after the states, symbolized the federal nature of the new republic, with power flowing from the states to the center and back again.

Sacred Geometry in Practice

The geometric principles weren’t merely aesthetic. L’Enfant intended to symbolize a reconciliation of heavenly and earthly powers, the spiritual and democratic ideals, in the geometry itself. The city’s design was meant to create what architecture theorist Will Selman calls a “temenos”—a sacred space that serves as a container for the psyche.

The Transformation of the Vision

L’Enfant’s vision was never fully realized. His dismissal by Washington in 1792 came after numerous conflicts with the city commissioners. The modifications that followed shifted the emphasis of the city’s design in subtle but important ways.

The Shift to Executive Power

Thomas Jefferson and others modified L’Enfant’s plan, giving much more emphasis in the city’s axes to the position of the White House—only completed in 1800—than to the Capitol building at the center of L’Enfant’s design. This shift perhaps reflected the political realities of the new nation, where executive power would play a larger role than initially envisioned.

The Incomplete Vision

The brilliant plan he offered was never fully completed, and was later significantly changed against his will. The reasons were both practical and political—L’Enfant’s refusal to release his plans for lot sales to raise money for construction ultimately led to his dismissal.

The Psychology of Power and Place

The design of Washington D.C. represents more than urban planning—it’s a psychological experiment in how physical space shapes political consciousness. The city’s layout embodies the tension between two competing visions of authority:

The Old Order: Divine Right Through Land

In the feudal system, power flowed downward from God through the king to the landed aristocracy. Physical space reinforced this hierarchy—the castle on the hill, the cathedral at the center, the walls that separated noble from commoner.

The New Order: Divine Right Through Enlightenment

The American experiment proposed that divine favor came not through inherited land but through the cultivation of reason and virtue. all government was a political institution between men naturally equal, not for the aggrandizement of one, or a few, but for the general happiness of the whole community.

The Continuing Relevance

Today, as we grapple with questions of authority, legitimacy, and power in our own time, L’Enfant’s vision—both realized and unrealized—offers important lessons:

- Physical Space Shapes Political Consciousness: The way we design our cities influences how we think about power and community.

- Symbolism Matters: The geometric and symbolic principles embedded in Washington’s design continue to influence how we perceive federal authority.

- Competing Visions Persist: The tension between L’Enfant’s people-centered design and the later executive-centered modifications reflects ongoing debates about the balance of power in democracy.

- Sacred Geometry Lives: Even in our secular age, the principles L’Enfant employed—the Golden Section, the sacred numbers—continue to create spaces that feel significant and meaningful.

The Unfinished Revolution

Washington D.C. stands as a monument to an unfinished revolution in human consciousness—the shift from authority based on inherited privilege to authority based on reason and consent. L’Enfant’s design, even in its modified form, continues to embody this transformation.

The city’s sacred geometry isn’t about occult conspiracies or hidden masters. It’s about the radical idea that ordinary people, through reason and virtue, could govern themselves. Every time we walk the Mall, every time we see the Capitol dome against the sky, we participate in this ongoing experiment.

As Nicholas Mann asks: if the symbolism of the capital city is intended to be a true expression of America’s heart, its innermost values, what can be done to restore the balance and integrity of its original, visionary principles? This question remains as relevant today as it was in 1791.

The psychology of Washington’s architecture reminds us that the built environment isn’t neutral—it’s a physical manifestation of our deepest beliefs about power, authority, and human dignity. In understanding L’Enfant’s vision, we better understand not just our capital, but ourselves.

More Articles on the Psychology of Architecture

The Psychology of Architecture

The Psychology of Architecture

The Corporate Post Modern Office

References and Further Reading

Primary Sources

- The L’Enfant Plan and related documents at the Library of Congress

- Washington’s correspondence regarding L’Enfant and the Federal City

- Jefferson’s notes on the capital’s design

Recommended Books

- Mann, Nicholas R. The Sacred Geometry of Washington, D.C.: The Integrity and Power of the Original Design. Green Magic, 2006. [The definitive work on the sacred geometric principles in L’Enfant’s design]

- Berg, Scott W. Grand Avenues: The Story of Pierre Charles L’Enfant, the French Visionary Who Designed Washington, D.C. Pantheon Books, 2007. [Comprehensive biography and analysis of L’Enfant’s work]

- Wasserman, James. The Secrets of Masonic Washington: A Guidebook to Signs, Symbols, and Ceremonies at the Origin of America’s Capital. Destiny Books, 2008. [Explores Masonic influences on the capital’s design]

Academic Articles

- Selman, Will. “L’Enfant’s Sacred Design for Washington DC.” Congress for the New Urbanism, February 21, 2018. [Contemporary urban planning perspective on L’Enfant’s design]

- Various authors. The Papers of George Washington, particularly volumes covering 1791-1792. [Primary source documents on the capital’s planning]

Online Resources

- The National Capital Planning Commission: www.ncpc.gov

- The Architect of the Capitol: www.aoc.gov

- Library of Congress L’Enfant Plan collection: www.loc.gov

Note: This article represents a synthesis of historical sources, architectural analysis, and philosophical interpretation. The connections between L’Enfant’s design and Enlightenment philosophy, while supported by historical evidence, involve some interpretive speculation, as L’Enfant left few written explanations of his symbolic intentions.

0 Comments