Why Does Architecture Change?

Architecture is not just a utilitarian practice of building shelter, but a profound expression of human psychology, culture, and politics. Throughout American history, architectural styles have served as a barometer of the nation’s collective psyche, reflecting the hopes, fears, values, and contradictions of each era. At the same time, architecture has also functioned as a tool of power and ideology, shaping the material and political realities of American society in ways that often mask and perpetuate deeper structures of inequality and domination.

This article traces the evolution of American architecture from the colonial period to the present day, exploring how different styles and movements have embodied the psychological, material, and political currents of their time. Drawing on the theories of depth psychology and Marxist materialism, it examines how architecture has both reflected and shaped the American experience, from the nation’s founding myths and traumas to its ongoing struggles for identity, meaning, and justice.

Early American Design: Colonial Period to 19th Century

Colonial Architecture (1600s-1700s)

From a psychological perspective, the Colonial Architecture of America can be seen as an expression of the archetypal struggle between the forces of light and darkness, civilization and wilderness, that shaped the early American psyche. The orderly grids and fortified walls of the New England towns represented an attempt to impose a sense of order and control on the threatening chaos of the New World, while the Gothic elements and haunted attics of the colonial revival style hinted at the repressed traumas and unresolved conflicts that lurked beneath the surface of the American dream.

From a material and political perspective, the Colonial Architecture of America can be seen as a reflection of the unequal distribution of land, labor, and capital that characterized the early stages of American capitalism. The simple, communal dwellings of the working classes stood in stark contrast to the opulent mansions of the wealthy elite, revealing the deep class divisions and power imbalances that shaped colonial society. At the same time, the erasure of indigenous architecture and the brutality of the slave quarters testified to the violence and exploitation that made such inequalities possible.

Greek Revival and Federal Architecture (1780s-1850s)

From a psychological perspective, the Federal and Greek Revival styles can be seen as expressions of the archetypal quest for order, harmony, and transcendence that shaped the American psyche in the early years of the republic. The classical forms and heroic sculptural programs of these styles tapped into the collective unconscious of Western civilization, offering a sense of continuity and legitimacy to the fledgling nation. At the same time, the shadow side of the American psyche found expression in the repressed traumas and unresolved conflicts of the early republic, including the legacy of slavery, the genocide of indigenous peoples, and the tensions between individual liberty and collective responsibility.

From a material and political perspective, the Federal and Greek Revival styles can be seen as a reflection of the growing power and influence of the mercantile and professional classes, who sought to legitimize their status through the appropriation of European high culture. The austere simplicity and geometric purity of the Greek Revival style also spoke to a more egalitarian and rationalist strain in the American character, one that rejected the ornamental excesses of the aristocratic past in favor of a more honest and functional approach to building. At the same time, the grand, imposing facades of the Greek Revival courthouse or state capitol projected an image of democratic ideals and the rule of law that belied the racial and class hierarchies that structured American society.

Gothic Revival and Romantic Architecture (1830s-1860s)

From a psychological perspective, the Gothic Revival can be seen as an expression of the collective unconscious’s yearning for a more mythic and numinous dimension of experience, one that transcended the narrow confines of reason and materialism. The shadowy interiors and soaring spires of the Gothic Revival church, for example, served as a symbolic gateway to the realm of the sacred and the supernatural, inviting the individual to confront the deeper mysteries of the psyche.

At the same time, the Romantic emphasis on nature, emotion, and individual genius can be seen as a manifestation of the Jungian archetype of the Self, which seeks to integrate the conscious and unconscious aspects of the personality into a harmonious whole. The organic forms and rustic materials of the Gothic Revival cottage, nestled in a picturesque landscape, offered a vision of a more authentic and fulfilling way of life, one that honored the primal bond between human and nature.

From a material and political perspective, the Gothic Revival and Romantic movements can be seen as a response to the social and economic dislocations of the industrial revolution, as well as the growing influence of the middle class and the rise of a new culture of domesticity and sentimentality. The elaborate ornamentation and irregular forms of Gothic Revival architecture expressed a sense of individuality and emotional warmth that appealed to the romantic sensibilities of the emerging bourgeoisie, while the picturesque landscapes and rustic cottages of the Romantic movement offered a nostalgic vision of a pre-industrial, agrarian past that masked the realities of class conflict and social inequality.

Victorian Eclecticism (1860s-1890s)

From a psychological perspective, Victorian eclecticism can be seen as an expression of the archetypal process of individuation, in which the ego confronts and integrates the multiple, often contradictory aspects of the self. The exuberant facades and eclectic interiors of the Victorian home can be seen as architectural manifestations of the persona, the social mask that the individual presents to the world in order to conform to cultural norms and expectations. At the same time, the shadow side of the Victorian psyche found expression in the dark, labyrinthine spaces of the Gothic revival, as well as in the uncanny doublings and monstrous transformations of late 19th century fantastic literature.

From a material and political perspective, Victorian eclecticism can be seen as a reflection of the unprecedented abundance and choice made possible by the industrial revolution, as well as the growing influence of consumerism and mass culture. The catalog houses and pattern books of the period encouraged a more fashion-driven and novelty-seeking approach to architecture that prioritized visual effect over structural integrity or social responsibility. At the same time, the Victorian fascination with historicism and exoticism can also be seen as a form of cultural appropriation and romanticization that masked the realities of imperialism, colonialism, and racial oppression.

Arts and Crafts Movement (1880s-1920s)

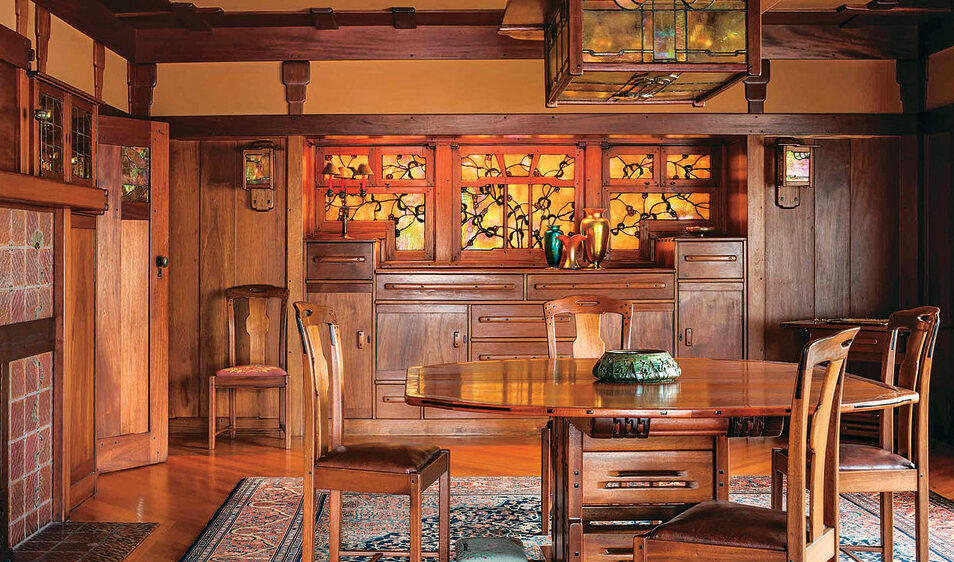

From a psychological perspective, the Arts and Crafts Movement can be seen as an expression of the archetypal desire for wholeness, integration, and spiritual meaning in the face of the fragmentation and disenchantment of modern life. The simple, organic forms and natural materials of Arts and Crafts design can be seen as an attempt to reconnect with the primal, instinctual aspects of the psyche that had been repressed and marginalized by the rationalist ethos of the Enlightenment and the industrial revolution.

At the same time, the shadow side of the Arts and Crafts Movement can be seen in its tendency towards nostalgia, sentimentality, and escapism, as well as in its failure to fully confront the structural inequalities and contradictions of capitalist society. The idealized vision of pre-industrial craftsmanship and rural life that animated much of the movement’s rhetoric and imagery can be seen as a form of romantic projection that masked the realities of poverty, exploitation, and social conflict in both the past and the present.

From a material and political perspective, the Arts and Crafts Movement can be seen as a response to the deskilling and degradation of labor that accompanied the rise of mass production and the factory system. By emphasizing the value of skilled craftsmanship and the dignity of manual labor, the movement sought to resist the commodification and standardization of work and to assert the creative agency and autonomy of the individual artisan. At the same time, the Arts and Crafts Movement also reflected the growing influence of socialist and anarchist ideas in the late 19th century, as well as the emergence of new forms of collective organization and social solidarity among workers and artisans.

20th Century Design: 1900s-1990s

Beaux-Arts and City Beautiful Movement (1890s-1920s)

From a psychological perspective, the Beaux-Arts and City Beautiful movements can be seen as expressions of the archetypal desire for order, beauty, and transcendence in the face of the chaos and squalor of the industrial city. The monumental public buildings and grand urban vistas of the Beaux-Arts style tapped into the collective unconscious of Western civilization, offering a sense of continuity and legitimacy to the American project of national greatness and imperial expansion. At the same time, the shadow side of the City Beautiful movement can be seen in its tendency towards authoritarianism, social control, and the suppression of difference and dissent in the name of aesthetic unity and civic virtue.

From a material and political perspective, the Beaux-Arts and City Beautiful movements can be seen as reflections of the growing concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a small corporate and financial elite, as well as the increasing role of the state in shaping the physical and social infrastructure of American cities. The monumental public buildings and grand urban ensembles of the period, such as the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 and the McMillan Plan for Washington, D.C., served as a kind of architectural propaganda that legitimized the authority of the ruling class and the ideology of American exceptionalism.

Art Deco and Streamline Moderne (1920s-1940s)

From a psychological perspective, the Art Deco and Streamline Moderne styles can be seen as expressions of the archetypal tension between the masculine and feminine principles, as well as the human desire for transcendence and escape from the limitations of the physical world. The phallic verticality and aggressive angularity of the Art Deco skyscraper, for example, can be seen as a manifestation of the archetypal masculine drive for power, conquest, and self-assertion, while the curvaceous forms and smooth surfaces of Streamline Moderne design suggest a more feminine emphasis on receptivity, flow, and sensual pleasure.

At the same time, the Art Deco and Streamline Moderne fascination with speed, flight, and the conquest of space can be seen as an expression of the archetypal human desire for transcendence and liberation from the constraints of gravity and materiality. The streamlined forms of the Chrysler Airflow car or the TWA Terminal at JFK Airport, for example, offered a vision of effortless motion and escape from the mundane realities of everyday life, tapping into the primal human fantasy of flying like a bird or rocketing into the heavens like a celestial being.

From a material and political perspective, the Art Deco and Streamline Moderne styles can be seen as reflections of the growing influence of mass production, advertising, and consumer culture on the American psyche and built environment. The sleek, stylized forms and luxurious materials of Art Deco design appealed to the aspirations and fantasies of the new middle class, while the aerodynamic curves and industrial materials of Streamline Moderne expressed a faith in the power of technology and engineering to solve social problems and create a better future. At the same time, the Art Deco and Streamline Moderne emphasis on novelty, glamour, and planned obsolescence can be seen as a form of cultural manipulation that served the interests of corporate capitalism and the culture industry.

International Style and Modernism (1930s-1970s)

The International Style and Modernist movements that emerged in the mid-20th century represented a radical break with the historicism and ornamentalism of the past, as well as a utopian vision of a new social order based on rationality, functionality, and universality. Inspired by the avant-garde experiments of European architects like Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius, as well as the social and technological innovations of the New Deal and World War II, American architects like Philip Johnson and Mies van der Rohe sought to create a universal language of design that would express the spirit of the modern age and the ideals of a more just and humane society.

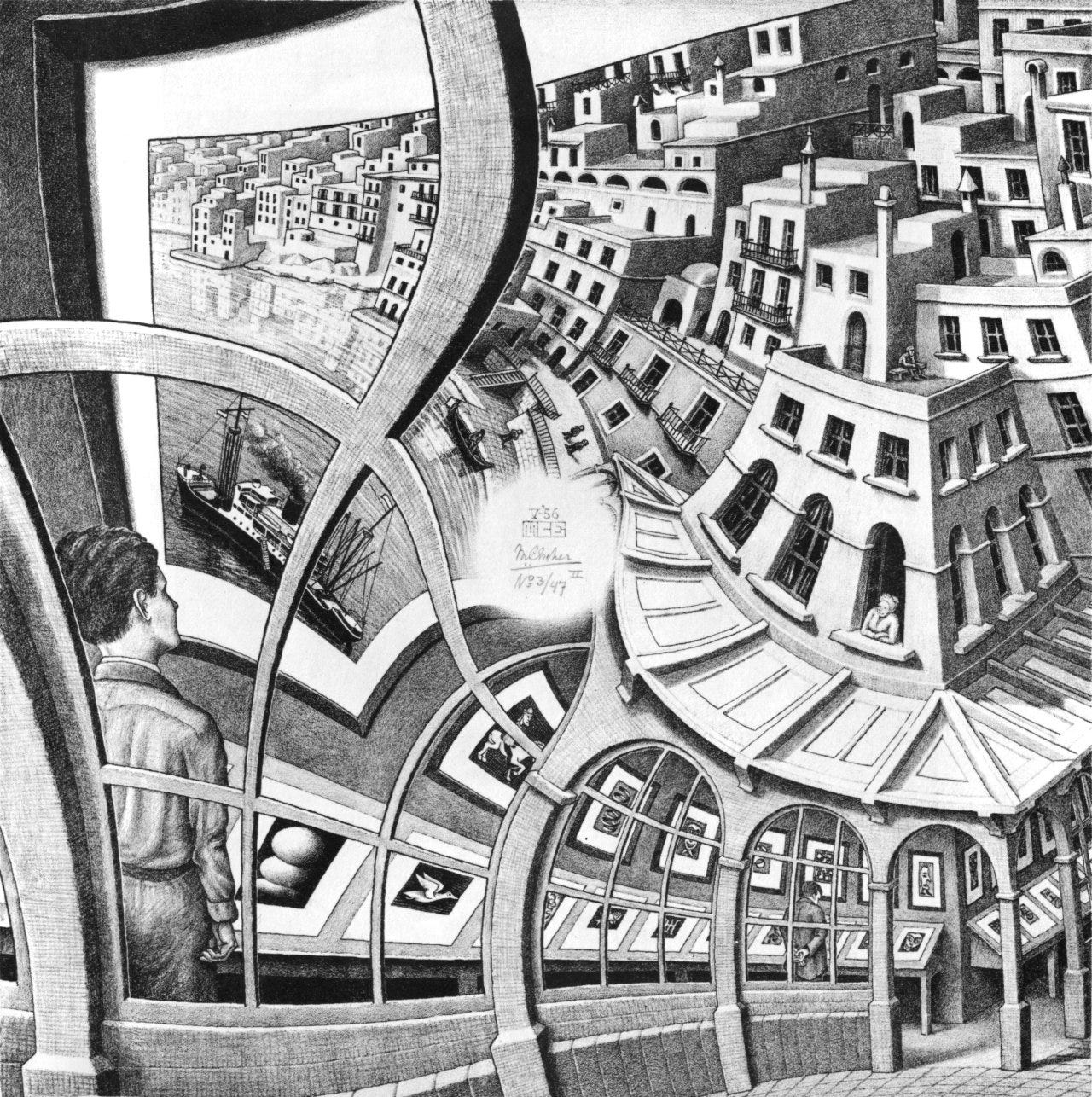

From a psychological perspective, the International Style and Modernist movements can be seen as expressions of the archetypal quest for transcendence, purity, and spiritual unity in the face of the chaos and fragmentation of the modern world. The abstract, geometric forms and white, luminous surfaces of Modernist architecture can be seen as an attempt to create a sense of order, clarity, and transcendence in a world that seemed increasingly irrational, uncertain, and meaningless. At the same time, the shadow side of Modernism can be seen in its tendency towards authoritarianism, conformity, and the suppression of individual differences and cultural diversity.

The repressed traumas and unresolved conflicts of the Modernist psyche found expression in the uncanny doubles and monstrous distortions of the Surrealist and Expressionist movements, as well as in the haunted spaces and fragmented forms of the post-war avant-garde. The ghostly presences and unspeakable absences that lurked beneath the surface of the Modernist utopia hinted at the darker aspects of the 20th century psyche that could not be fully contained or controlled by the rational order.

From a material and political perspective, the International Style and Modernist movements can be seen as reflections of the growing power and influence of corporate capitalism in the postwar era, as well as the increasing role of the state in shaping the built environment through public housing, urban renewal, and infrastructure projects. The abstract, repetitive forms of the International Style office tower or the Modernist public housing block, for example, can be seen as architectural expressions of the standardization, rationalization, and bureaucy.

From a material and political perspective, the International Style and Modernist movements can be seen as reflections of the growing power and influence of corporate capitalism in the postwar era, as well as the increasing role of the state in shaping the built environment through public housing, urban renewal, and infrastructure projects. The abstract, repetitive forms of the International Style office tower or the Modernist public housing block, for example, can be seen as architectural expressions of the standardization, rationalization, and bureaucratization of modern life under the regime of Fordist mass production and Keynesian state regulation.

Post-War Suburbanization and the Ranch House (1940s-1960s)

The mass suburbanization of America in the post-World War II period, fueled by the GI Bill, the Interstate Highway System, and the rise of the automobile, led to the proliferation of new architectural forms like the ranch house that reflected the values and aspirations of the burgeoning middle class. With its open-plan layout, picture windows, and seamless integration of indoor and outdoor spaces, the ranch house expressed a sense of informality, domesticity, and connection to nature that stood in contrast to the more formal and hierarchical spatial arrangements of earlier housing types.

From a psychological perspective, the ranch house can be seen as an architectural manifestation of the persona, the social mask that the individual presents to the world in order to fit in and be accepted by the collective. The facade of the ranch house, with its neat lawn, picket fence, and pastel-colored appliances, served to conceal the deeper anxieties, repressions, and contradictions of the postwar psyche, including the trauma of the war, the threat of nuclear annihilation, and the alienation of the organization man.

At the same time, the mass-produced, standardized character of suburban tract housing developments like Levittown can be seen as a reflection of the increasing homogenization and conformity of American society under the regime of Fordist capitalism and the military-industrial complex. The identical rows of houses and the uniform lifestyle they implied can be seen as a form of social control and psychological conditioning that served to suppress individual differences and maintain the status quo.

From a material and political perspective, the post-war suburbanization of America can be seen as a spatial fix for the crisis of overaccumulation and underconsumption that threatened the stability of the capitalist system after the war. By channeling the surplus capital and labor of the postwar boom into the construction of suburban housing and infrastructure, the state and the private sector were able to create new markets for consumer goods and services, as well as new forms of social and spatial segregation that reinforced the racial and class hierarchies of American society.

The Countercultural Turn and Postmodern Historicism (1960s-1980s)

From a psychological perspective, the turn to historical eclecticism and symbolic ornamentation in postmodern architecture can be seen as an attempt to reconnect with the archetypal imagery and collective unconscious of the past, which had been repressed and marginalized by the rationalist ethos of modernism. The colorful, figurative, and often ironic facades of postmodern buildings like Venturi’s Guild House or Moore’s Piazza d’Italia served to re-enchant and re-narrativize the built environment, tapping into the deep psychological need for myth, meaning, and identity in a rapidly changing and disorienting world.

At the same time, the postmodern turn to historicism and contextualism can also be seen as a compensatory response to the economic and social dislocations of the 1970s, including the oil crisis, stagflation, and the decline of industrial manufacturing. As the postwar consensus unraveled and the American Dream of upward mobility and material prosperity began to fade, many people sought solace and stability in the familiar forms and traditional values of the past. The rise of New Urbanism in the 1980s and 90s, with its nostalgic evocation of small-town America and its focus on walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods, can be seen as an attempt to recreate a sense of community and place in the face of the sprawling, atomized landscapes of suburbia and the placeless non-places of the postmodern city.

From a material and political perspective, the countercultural turn and postmodern historicism can be seen as a reflection of the crisis of Fordism and the rise of a new, post-industrial economy based on information, services, and flexible accumulation. The fragmented, layered, and collage-like forms of postmodern architecture can be seen as an expression of the increasing complexity and volatility of global capitalism, as well as the growing influence of media, advertising, and consumer culture on the built environment. At the same time, the critical and subversive strategies of postmodern architects and theorists can be seen as a way of challenging the hegemonic power of corporate capitalism and the state, and of imagining new forms of social and spatial organization that are more democratic, inclusive, and equitable.

The Oil Crisis and the Passive Solar Movement (1970s-1980s)

From a psychological perspective, the passive solar movement can be seen as an expression of the archetypal desire for harmony and balance with the natural world, which had been disrupted by the hubris and alienation of industrial modernity. The organic, site-specific forms of passive solar architecture, which often drew on vernacular and indigenous building traditions, served to reconnect the individual with the primal rhythms and cycles of nature, tapping into the collective unconscious of pre-modern cultures that lived in greater ecological and spiritual attunement with the earth.

At the same time, the passive solar movement can also be seen as a reaction against the excesses and contradictions of the postwar consumer society, which had become increasingly dependent on cheap, abundant energy to fuel its growth and expansion. As the limits of this fossil-fueled model became apparent, many people began to question the values and assumptions of the American Dream itself, seeking alternative ways of living that were more ecologically and socially sustainable. The rise of the back-to-the-land movement, the counterculture, and the environmental movement in the 1970s can be seen as part of this larger shift in consciousness, which found expression in the simple, self-sufficient, and low-impact designs of passive solar architecture.

From a material and political perspective, the oil crisis and the passive solar movement can be seen as a reflection of the growing contradictions and instabilities of the Fordist regime of accumulation, which had reached its limits in the face of rising energy costs, international competition, and social unrest. The turn to renewable energy and sustainable design in the 1970s and 80s can be seen as a way of addressing these contradictions and imagining new forms of production and consumption that were more ecologically and socially just. At the same time, the passive solar movement also reflected the growing influence of the environmental movement and the emergence of new forms of grassroots activism and community organizing that challenged the top-down, technocratic approach of the state and the market.

Postmodern Classicism and New Urbanism (1980s-2000s)

The Postmodern Classicist and New Urbanist movements that emerged in the 1980s and 1990s represented a critique of the abstract, placeless, and anti-urban tendencies of modernist architecture and planning, as well as a desire to reconnect with the traditional forms, typologies, and urban patterns of the pre-modern city. Inspired by the theoretical writings and built work of architects like Leon Krier and Andres Duany, as well as the social and environmental critiques of Jane Jacobs and Christopher Alexander, a new generation of architects and planners sought to revive the classical language and human scale of traditional urbanism, while adapting it to the needs and complexities of contemporary society.

From a psychological perspective, the Postmodern Classicist and New Urbanist movements can be seen as expressions of the archetypal desire for order, harmony, and meaning in the face of the fragmentation and alienation of the modern city. The symmetrical, hierarchical, and ornamental forms of classical architecture, as well as the walkable, mixed-use, and human-scaled environments of traditional urbanism, can be seen as an attempt to reconnect with the collective unconscious of Western civilization, tapping into the deep psychological structures and symbolic meanings that have shaped human settlements for millennia.

At the same time, the Postmodern Classicist and New Urbanist emphasis on place-making, community-building, and civic engagement can be seen as a way of fostering a sense of belonging, identity, and empowerment among urban dwellers, in contrast to the anonymity, isolation, and powerlessness of the modernist city. Projects like Seaside, Florida, designed by Andres Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, or Poundbury, England, masterplanned by Leon Krier, can be seen as attempts to create more livable, sociable, and sustainable urban environments that balance the needs of the individual with the values of the community.

From a material and political perspective, the Postmodern Classicist and New Urbanist movements can be seen as a reflection of the increasing disillusionment with the failures and unintended consequences of modernist urban planning and social engineering, as well as the search for alternative models of development that are more responsive to local contexts, histories, and cultures. The top-down, technocratic approach of modernist planning, with its emphasis on functional zoning, automotive mobility, and mass housing, can be seen as a form of spatial and social control that reinforced the power of the state and the market, while marginalizing the agency and creativity of local communities.

In contrast, the bottom-up, participatory approach of New Urbanism, with its focus on codes, patterns, and incremental development, can be seen as a way of empowering communities to shape their own environments, while creating more adaptable, resilient, and equitable forms of urbanism. At the same time, the historicist and traditionalist aesthetics of Postmodern Classicism can also be seen as a form of cultural nostalgia and conservatism that romanticizes the pre-modern past, while ignoring its social and political contradictions and inequalities.

In this context, the challenge for Postmodern Classicism and New Urbanism is to develop a more critical and reflexive approach to the classical tradition and the urban heritage, one that acknowledges its complicity with the structures of power and domination, while also recognizing its potential for resistance, subversion, and transformation. This may involve a re-interpretation of the classical language and the traditional city as a site of difference, multiplicity, and contestation, rather than a static and homogeneous ideal. It may also involve a more radical questioning of the underlying assumptions and value systems of Western modernity, including the myths of progress, individualism, and universalism that have shaped the built environment and the social imaginary.

Architectural projects like Leon Krier’s masterplan for the new town of Cayala in Guatemala, which combines classical typologies with local vernacular traditions and social programs, or Andres Duany’s agrarian urbanism model, which integrates food production and ecological stewardship into the urban fabric, can be seen as examples of this more critical and transformative approach to Postmodern Classicism and New Urbanism. These projects not only seek to create more beautiful, livable, and sustainable urban environments, but also to challenge the dominant paradigms of globalization, consumerism, and environmental degradation, while fostering new forms of community, solidarity, and resilience.

From a Jungian perspective, the Postmodern Classicist and New Urbanist movements can be seen as an expression of the archetypal quest for wholeness and individuation in the face of the disenchantment and fragmentation of the modern world. The reintegration of the classical and the vernacular, the urban and the rural, the individual and the collective, can be seen as an attempt to heal the split between culture and nature, mind and body, self and other that has characterized Western thought since the Enlightenment. By re-engaging with the symbolic and mythical dimensions of the built environment, as well as the ecological and social processes that sustain it, Postmodern Classicism and New Urbanism offer a new vision of the city as a living organism and a sacred landscape, in which humans and non-humans alike participate in the unfolding of a more balanced, meaningful, and regenerative way of life.

Deindustrialization and the Postmodern Corporate Headquarters (1980s-2000s)

From a psychological perspective, the postmodern corporate headquarters can be seen as an architectural manifestation of the persona of the new knowledge worker, who was expected to be creative, adaptable, and always on in a 24/7 digital economy. The transparent, fluid spaces of these buildings, with their emphasis on collaboration, networking, and self-management, served to normalize and naturalize the precarious, immaterial labor of the post-Fordist workplace, with its blurred boundaries between work and life, production and consumption, the individual and the corporation.

At the same time, the postmodern corporate headquarters can also be seen as a compensatory response to the decline of the traditional manufacturing economy and the erosion of the social contract between labor and capital. As the stable, long-term employment of the postwar period gave way to a more flexible, contingent model of work, many corporations sought to project an image of community, belonging, and purpose through the design of their buildings and campuses. The atriums, courtyards, and town squares of postmodern corporate architecture served to create a sense of place and identity in the placeless, global space of the new economy, tapping into the deep psychological need for rootedness and connection in an increasingly atomized and alienated society.

From a material and political perspective, the postmodern corporate headquarters can be seen as a reflection of the increasing power and influence of multinational corporations in the age of neoliberal globalization. The iconic, sculptural forms of these buildings, often designed by celebrity architects like Frank Lloyd Wright and Zaha Hadid, served as a form of architectural branding and cultural capital that reinforced the hegemonic status of the corporate elite. At the same time, the lavish, high-tech interiors of these buildings, with their gourmet cafeterias, fitness centers, and recreational amenities, can be seen as a form of corporate welfare that masked the growing inequalities and precarity of the postindustrial workforce.

21st Century Design: 2000s to Present

Neo-Modernism and Parametricism (2000s-2010s)

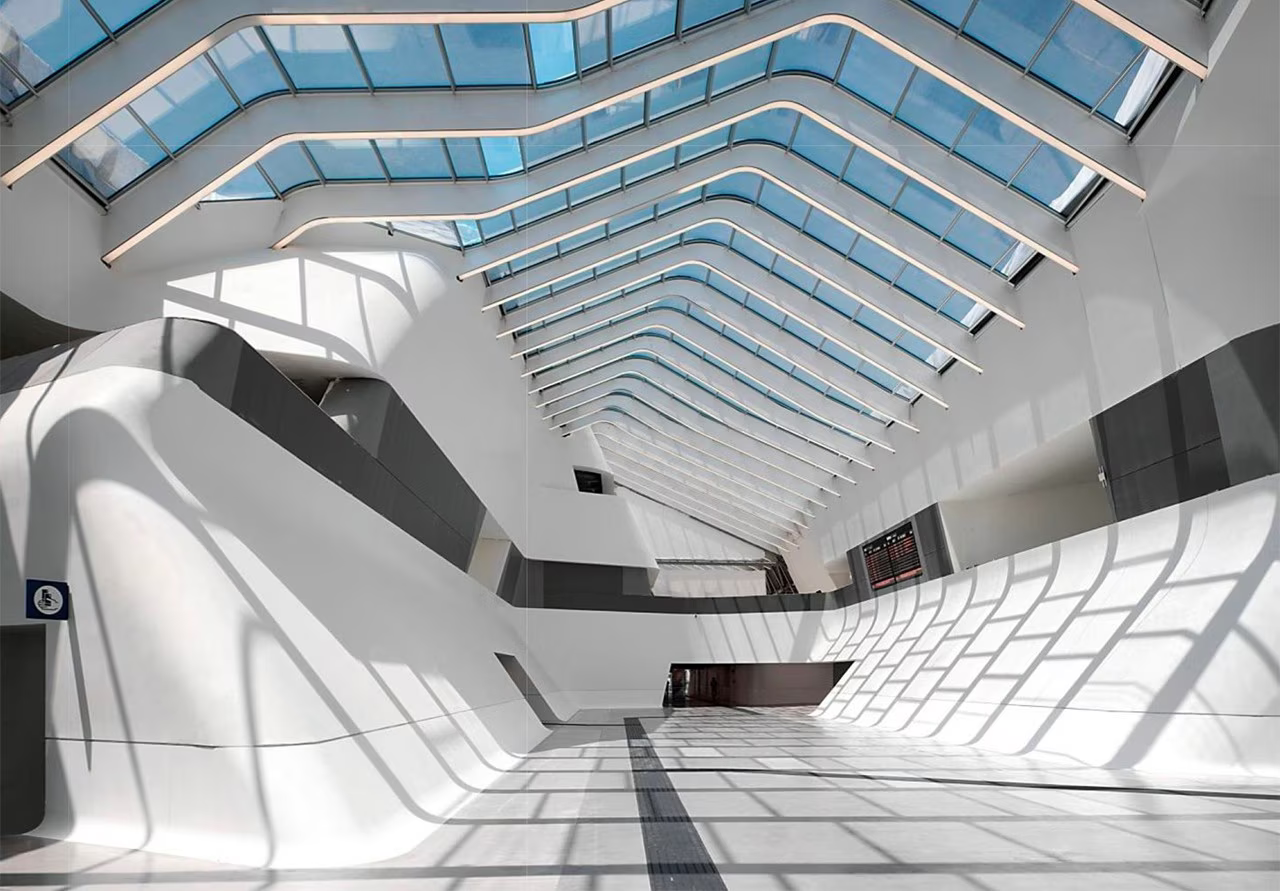

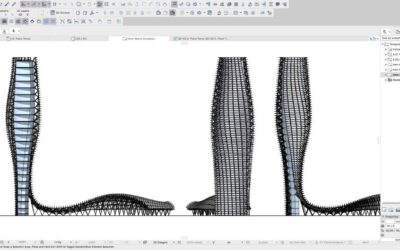

The Neo-Modernist and Parametricist movements that emerged in the early 21st century represented a renewed interest in the formal and technological innovations of the modernist avant-garde, as well as a desire to harness the power of digital tools and computational methods to create a more responsive, adaptive, and sustainable built environment. Inspired by the work of pioneering architects like Zaha Hadid and Rem Koolhaas, as well as the theoretical writings of Patrik Schumacher and the research of the AA Design Research Lab, a new generation of architects and designers sought to push the boundaries of formal experimentation and performance-based design, often using advanced software and fabrication techniques to generate complex, fluid, and dynamic forms and spaces.

From a psychological perspective, the Neo-Modernist and Parametricist movements can be seen as expressions of the archetypal drive for growth, transformation, and individuation in the face of new challenges and opportunities. The dynamic, fluid forms of Neo-Modernist buildings like Hadid’s Heydar Aliyev Center or Koolhaas’s CCTV Headquarters, for example, can be seen as architectural metaphors for the Jungian process of psychological transformation, in which the individual ego is stretched, deformed, and ultimately reborn into a more complex, integrated, and authentic self.

At the same time, the Parametricist emphasis on emergence, self-organization, and adaptation can be seen as a way of tapping into the generative, evolutionary potential of the collective unconscious, as well as the creative, transformative power of the natural world. The complex, organic forms of Parametricist buildings like Schumacher’s Kartal-Pendik Masterplan or the AA’s Driftwood Pavilion, for example, can be seen as architectural expressions of the Jungian archetype of the “Self,” the central, organizing principle of the psyche that guides the individual towards greater wholeness, meaning, and purpose.

From a material and political perspective, the Neo-Modernist and Parametricist movements can be seen as a reflection of the increasing complexity and uncertainty of the global economy in the age of digital capitalism. The fluid, networked forms of these buildings, with their emphasis on flexibility, adaptability, and continuous innovation, can be seen as an expression of the post-Fordist logic of accumulation, with its focus on immaterial labor, cognitive capitalism, and the valorization of creativity and knowledge. At the same time, the techno-utopian rhetoric and futuristic imagery of these movements can also be seen as a form of ideological mystification that masks the growing inequalities and contradictions of the neoliberal order, as well as the ecological and social costs of unbridled growth and technological progress.

The Housing Crisis and Post-Bubble Architecture (2000s-2010s)

The global financial crisis of 2008, triggered by the collapse of the subprime mortgage market and the bursting of the housing bubble, led to a deep recession and a wave of foreclosures that devastated many American communities. In the aftermath of the crisis, a new generation of architects and planners began to question the speculative logic and unsustainable practices of the pre-bubble era, seeking to develop new models of housing and urbanism that prioritized affordability, sustainability, and social equity.

From a psychological perspective, the housing crisis can be seen as a collective trauma that shattered the American Dream of homeownership and upward mobility, revealing the deep insecurities and contradictions of the neoliberal psyche. The wave of foreclosures and evictions that swept the country in the wake of the crisis can be seen as a form of psychological displacement and dispossession, as millions of Americans lost their homes, their savings, and their sense of identity and belonging. At the same time, the crisis also served as a catalyst for a new kind of architectural imagination, one that sought to reconnect with the embodied, relational, and place-based aspects of human experience that had been marginalized by the abstract, disembodied logic of financialization.

The rise of post-bubble architecture in the 2010s, with its emphasis on adaptive reuse, incremental development, and community participation, can be seen as an attempt to heal the wounds of the crisis and to rebuild a sense of social and spatial solidarity in the face of economic and ecological upheaval. Projects like the Heidelberg Project in Detroit, which transforms abandoned houses into works of art and community spaces, or the R-Urban network in Paris, which creates a network of locally managed hubs for urban resilience and civic ecology, can be seen as expressions of a new kind of architectural activism that seeks to empower communities and to create alternative models of development that are more equitable, sustainable, and democratic.

From a material and political perspective, the housing crisis and post-bubble architecture can be seen as a reflection of the crisis of neoliberalism and the search for new forms of social and economic organization in the face of growing inequality, precarity, and ecological collapse. The speculative excesses and predatory lending practices of the pre-bubble era can be seen as a symptom of the increasing financialization of the economy and the commodification of housing as an asset class, rather than a basic human right. The rise of post-bubble architecture, with its focus on social housing, cooperative ownership, and community land trusts, can be seen as a way of challenging the hegemonic logic of the market and asserting the value of the commons and the public good.

At the same time, the post-bubble era has also seen the rise of new forms of spatial inequality and social polarization, as the crisis has accelerated the concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a small elite, while leaving many communities behind. The proliferation of luxury condos, gated communities, and privatized public spaces in many cities can be seen as a form of architectural apartheid that reinforces the social and spatial segregation of the neoliberal order. In this context, the challenge for post-bubble architecture is to develop new forms of spatial justice and urban solidarity that can resist the forces of gentrification and displacement, while creating more inclusive, equitable, and sustainable models of development.

Climate Crisis Architecture and New Materialism (2010s-present)

From a psychological perspective, this new ecological consciousness reflects a growing awareness of the deep interconnectedness of human and non-human systems, and the need for a more holistic and integrated approach to the built environment. The climate crisis has brought the repressed and denied aspects of the human-nature relationship to the surface, forcing a confrontation with the shadow side of modernity’s domination and exploitation of the natural world. At the same time, the rise of new materialist philosophies like speculative realism, object-oriented ontology, and vital materialism reflect a desire to re-enchant and re-sacralize the material world, recognizing the intrinsic value and agency of non-human entities and systems.

Architectural projects like SCAPE’s Living Breakwaters in Staten Island, New York, or the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway, reflect this new ecological and philosophical sensibility, blurring the boundaries between nature and culture, the organic and the inorganic, the living and the non-living. From a Jungian perspective, these projects can be seen as an effort to re-integrate the repressed and marginalized aspects of the psyche into the built environment, creating spaces that foster a sense of interconnectedness, responsibility, and awe towards the more-than-human world. At the same time, they reflect a growing awareness of the shadow side of human exceptionalism and the need for a more humble and responsive approach to the built environment in the face of existential threats like climate change.

From a material and political perspective, the rise of climate crisis architecture and New Materialism can be seen as a reflection of the increasing urgency and complexity of the ecological crisis, as well as the failure of the neoliberal order to address the root causes and systemic challenges of climate change and environmental degradation. The market-based solutions and techno-fixes of green capitalism, such as carbon trading, renewable energy, and smart cities, can be seen as a form of greenwashing that fails to challenge the underlying logic of growth, extraction, and consumption that drives the crisis. At the same time, the top-down, centralized approach of state-led interventions, such as large-scale infrastructure projects and geo-engineering schemes, can be seen as a form of eco-authoritarianism that disempowers communities and reinforces existing power structures.

In this context, the challenge for climate crisis architecture and New Materialism is to develop new forms of ecological democracy and environmental justice that can bridge the gap between top-down and bottom-up approaches, while creating more regenerative, resilient, and equitable models of development. This may involve a rediscovery of indigenous and vernacular building traditions, a re-localization and re-democratization of the building process, and a re-sacralization of the natural world as a source of meaning, identity, and spiritual renewal. It may also involve a confrontation with the deeper psychological and cultural roots of the crisis, including the Western myths of separation, domination, and progress that have shaped the modern world.

Architectural projects like the Living Building Challenge, which seeks to create buildings that generate more energy and resources than they consume, or the Dark Matter Gardens in Helsinki, which explores the potential of mycelium and other biological materials as a sustainable alternative to concrete and steel, can be seen as examples of this new ecological and materialist sensibility in action. These projects not only seek to reduce the environmental impact of the built environment, but also to create new forms of symbiosis and co-evolution between human and non-human systems, challenging the anthropocentric assumptions of Western culture and creating new narratives and imaginaries for a post-carbon, post-growth future.

Post-Digital and New Materialism (2010s-Present)

From a psychological perspective, the Post-Digital and New Materialism turn reflects a desire to reconnect with the embodied, embedded, and relational aspects of human experience that have been marginalized by the abstract, disembodied logic of digital capitalism and the attention economy. The proliferation of haptic, multi-sensory, and immersive interfaces in contemporary architecture and design, such as the use of responsive materials, augmented reality, and virtual environments, can be seen as an attempt to re-engage the body and the senses in the process of spatial production and perception, creating more affective, empathetic, and meaningful experiences of place and identity.

At the same time, the Post-Digital and New Materialism movements also reflect a growing awareness of the ecological and ethical implications of the digital infrastructure and supply chains that underpin the global economy, from the extraction of rare earth minerals and the exploitation of cheap labor to the e-waste and energy consumption generated by the tech industry. In this context, the turn towards bio-based materials, circular economies, and regenerative design can be seen as an attempt to create more sustainable and equitable forms of production and consumption, while also exploring new forms of human and non-human collaboration and co-creation.

From a material and political perspective, the Post-Digital and New Materialism movements can be seen as a reflection of the increasing complexity and uncertainty of the global economy in the age of the Anthropocene, as well as the need for new forms of social and ecological resilience in the face of climate change, resource depletion, and geopolitical instability. The decentralized, distributed, and open-source models of design and fabrication enabled by digital technologies, such as 3D printing, CNC milling, and robotic construction, can be seen as a way of democratizing access to the means of production and empowering communities to create their own solutions to local challenges, while also fostering new forms of collaboration and knowledge-sharing across borders and disciplines.

At the same time, the Post-Digital and New Materialism movements also reflect a growing awareness of the political and ethical dimensions of the built environment, and the need for new forms of spatial justice and environmental activism in the face of rising inequality, displacement, and ecological devastation. Architectural projects like the Microbial Home by Philips Design, which explores the potential of living organisms as a source of energy, food, and waste management, or the Mycelium Martian Dome by NASA, which proposes using fungal materials to build habitats on Mars, can be seen as examples of this new post-digital and new materialist sensibility in action, blurring the boundaries between nature and culture, technology and biology, science and fiction.

From a Jungian perspective, the Post-Digital and New Materialism movements can be seen as an expression of the archetypal quest for wholeness and individuation in the face of the fragmentation and alienation of the modern world. The reintegration of the material and the digital, the organic and the technological, the human and the non-human, can be seen as an attempt to heal the split between nature and culture, mind and body, self and other that has characterized Western thought since the Enlightenment. By re-engaging with the material world as a source of meaning, agency, and transformation, rather than as a passive resource to be exploited and consumed, the Post-Digital and New Materialism movements offer a new vision of the built environment as a co-evolutionary process of becoming, in which humans and non-humans alike participate in the unfolding of a more regenerative, resilient, and equitable future.

Looking to the Future of Architecture

As we have seen, the history of American architecture and design is a complex and contested terrain, shaped by a wide range of psychological, material, and political forces. From the colonial period to the present day, the built environment has served as a mirror and a catalyst for the hopes, fears, and contradictions of American society, reflecting both the dominant ideologies and power structures of each era, as well as the counter-hegemonic movements and alternative visions that have challenged and transformed them.

By tracing the evolution of American architecture through the lens of Jungian psychology and Marxist materialism, we can begin to unpack the deep cultural and political meanings embedded in the built environment, and to imagine new forms of spatial production and social organization that are more just, equitable, and sustainable. Whether through the rediscovery of vernacular traditions and ecological knowledge, the democratization of design and fabrication processes, or the re-sacralization of the natural world and the more-than-human, the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century call for a new kind of architectural imagination and practice, one that can bridge the gap between the individual and the collective, the local and the global, the material and the digital, the human and the non-human.

In this context, the role of architecture and design becomes not only to create functional and aesthetically pleasing spaces, but also to facilitate new forms of social and ecological relationships, to foster a sense of belonging and empowerment among communities, and to contribute to the regeneration and resilience of the planet as a whole. This requires not only a new set of technical skills and knowledge, but also a new ethical and political consciousness, one that recognizes the interconnectedness and interdependence of all beings, and the responsibility of humans to act as stewards and co-creators of the world we inhabit.

As we move forward into an uncertain and rapidly changing future, the lessons of the past can serve as a guide and an inspiration for a new generation of architects, designers, and activists, who are working to create a more just, equitable, and sustainable built environment for all. By embracing the complexity and diversity of the American experience, and by engaging with the deeper psychological and political dimensions of the built environment, we can begin to imagine and build a future that is more inclusive, regenerative, and resilient, one that honors the rich tapestry of human and non-human life on this planet, and that contributes to the flourishing of all beings for generations to come.

0 Comments