What is the Window of Tolerance in Psychology?

In the realm of psychology and personal growth, the concept of the “window of tolerance” has emerged as a powerful framework for understanding the dynamics of stress, emotional regulation, and resilience. First coined by psychiatrist Dr. Dan Siegel, the term refers to the optimal zone of arousal where a person is able to function most effectively – neither too overwhelmed nor too disengaged.

Interestingly, while the specific language of the “window of tolerance” is a relatively recent development in Western psychology, the core ideas it points to have deep roots in both Eastern contemplative traditions and Western psychotherapeutic approaches. By exploring these resonances and parallels, we can gain a richer, more integrated understanding of what it means to live and thrive within our “window.”

The Window of Tolerance: An Overview

So what exactly is the window of tolerance? In simple terms, it’s the range of activation in which an individual is able to respond to life’s challenges with flexibility, adaptiveness, and coherence. When we’re within our window, we feel grounded, centered, and capable of engaging with the full spectrum of our emotions without becoming overwhelmed or shutting down.

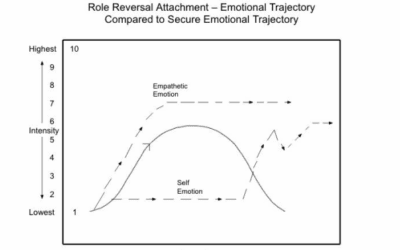

But when we’re pushed outside our window – whether through acute stress, trauma, or accumulated strain – our nervous system can tip into states of either hyper-arousal or hypo-arousal. In hyper-arousal, we may feel anxious, panicky, angry, or out of control. In hypo-arousal, we may feel numb, disconnected, depressed, or unable to mobilize. Both of these states can significantly limit our capacity for clear thinking, emotional balance, and effective action.

One helpful way to visualize the window of tolerance is as a kind of “Goldilocks zone” – not too much, not too little, but just right. Like a rose that needs the right balance of sunlight, water, and nutrients to blossom, we all have an optimal range of stimulation and challenge that allows us to grow and thrive.

But our windows can also shrink or expand based on our life experiences, coping skills, and support systems. Chronic stress, unresolved trauma, or lack of secure attachment in childhood can lead to a narrowed window, making us more vulnerable to becoming overwhelmed or shutting down. On the other hand, consistent practices of self-care, healthy relationships, and mind-body integration can help to widen our window over time.

Eastern Roots of the Window of Tolerance

While the specific term “window of tolerance” is a modern coinage, the concept has striking parallels in many Eastern wisdom traditions. One of the clearest examples is the Buddhist notion of the “middle way” or “middle path.”

According to Buddhist teachings, the path to enlightenment lies in avoiding the extremes of either indulgence or austerity, and instead finding a balanced, moderate approach to life. This isn’t a static point, but a dynamic dance of continuously adjusting our actions, attitudes, and attention to stay within a range of optimal responsiveness and clarity.

We can see this idea reflected in the Buddha’s own life story. As a young prince, Siddhartha Gautama lived a life of extreme luxury and indulgence, shielded from the realities of suffering and death. When he finally ventured outside the palace walls and encountered old age, sickness, and mortality for the first time, he was plunged into a state of existential crisis and despair.

In an attempt to find liberation from suffering, Siddhartha then swung to the opposite extreme, renouncing all worldly attachments and engaging in severe ascetic practices. But after nearly starving himself to death, he realized that this path of self-mortification was just as unbalanced and unhelpful as his previous life of excess.

It was only when Siddhartha found the “middle way” between these extremes – neither indulging in sensual pleasures nor denying the body’s basic needs – that he was able to settle into a state of profound equanimity and insight, ultimately leading to his awakening as the Buddha.

This principle of finding the “just right” balance between extremes is central to Buddhist psychology and practice. In mindfulness meditation, for example, practitioners are often encouraged to find the “sweet spot” of attention – neither too tight and rigid, nor too loose and diffuse. This optimal attentional stance allows for a kind of relaxed alertness, a state of being present with one’s moment-to-moment experience without getting lost in thought or drifting off into dullness.

Similarly, in the Zen tradition, there’s a well-known teaching that compares the mind to the strings of a musical instrument. If the strings are too tight, they’ll produce a sharp, jarring sound. If they’re too loose, the sound will be dull and lifeless. But if the strings are tuned just right – not too taut, not too slack – the instrument will create music of exquisite beauty and resonance.

We could say that these teachings all point to a kind of inner “window of tolerance” – a state of being in which we’re neither too rigid nor too scattered, neither too intense nor too dull, but attuned and responsive to the needs of the moment.

The Bhagavad Gita, a sacred Hindu text, also offers a powerful metaphor for this state of dynamic balance. In one famous passage, the god Krishna compares the self-controlled yogi to a candle flame that remains steady in a windless place, without flickering or wavering. This unwavering flame of awareness is contrasted with the turbulent, wind-tossed mind that is easily agitated by sense impressions and desires.

But the goal here isn’t a kind of rigid, artificial stillness – it’s a natural stability that comes from being deeply rooted in one’s own center. Like a tree that sways gracefully in the breeze but remains firmly planted in the earth, the yogi is able to respond to life’s vicissitudes with flexibility and resilience, without losing touch with the ground of being.

Western Parallels and Applications

While the language may differ, we can find striking resonances with the window of tolerance concept in various Western psychotherapeutic approaches as well. One clear example is the “zone of proximal development” in Lev Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory.

According to Vygotsky, the zone of proximal development (ZPD) is the distance between what a learner can do without help and what they can do with guidance and encouragement from a skilled partner. In other words, it’s the sweet spot where a task is neither too easy nor too difficult, but just challenging enough to facilitate growth and learning.

We could say that the ZPD is a kind of “window of tolerance” for cognitive and skill development. If a task is too far below the learner’s current abilities, they’ll quickly become bored and disengaged. If it’s too far beyond their capacities, they’ll likely feel overwhelmed and frustrated. But if the task is within their ZPD – just on the edge of what they can do with support – it creates an optimal state of engagement, motivation, and growth.

This idea has powerful implications for therapy, education, and personal development. By calibrating challenges and support to stay within a person’s ZPD, we can create the conditions for sustained learning, skill-building, and self-expansion. And by gradually stretching the boundaries of the ZPD over time, we can help individuals grow their capacities and widen their window of tolerance.

We can see a similar principle at work in the concept of “eustress” or positive stress. While we often think of all stress as harmful, a certain amount of challenge and stimulation is actually crucial for mental and physical well-being. Exposure to moderate, manageable stressors – whether it’s physical exercise, intellectual puzzle-solving, or stepping outside our comfort zone in relationships – can help to build resilience, adaptability, and a sense of mastery.

The key, of course, is staying within our window of tolerance – not pushing so far that we become overwhelmed, but not staying so “safe” that we stagnate. Like a muscle that needs just the right amount of resistance to grow stronger, our psychological and emotional capacities need just the right amount of challenge to develop.

This idea is central to many approaches in cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), which emphasize the importance of gradual exposure to feared or avoided situations. By slowly and systematically confronting anxiety-provoking stimuli – while staying grounded and resourced within the window of tolerance – individuals can rewire their threat-detection systems and expand their capacity for calm, centered engagement.

Similarly, in body-based therapies like Somatic Experiencing or Sensorimotor Psychotherapy, there’s a strong emphasis on helping clients develop greater resilience and capacity for self-regulation. By tuning into the felt sense of the body and learning to track and modulate arousal states, individuals can widen their window of tolerance and develop a more flexible, adaptive response to stress and challenge.

Integrating the Wisdom of East and West

As we’ve seen, the concept of the window of tolerance – while rooted in modern neuroscience and attachment theory – has deep resonances with both Eastern contemplative traditions and Western therapeutic approaches. By drawing on this integrated understanding, we can develop a more holistic, embodied approach to living and thriving within our optimal zone of well-being.

Some key principles and practices that can help to widen the window of tolerance include:

- Mindfulness and self-awareness: Developing a greater capacity to notice and track our moment-to-moment experience – thoughts, emotions, sensations, and impulses – without getting lost in reactivity or judgment. This allows us to catch ourselves earlier when we start to move outside our window, and to respond with greater skill and flexibility.

- Grounding and centering: Cultivating a felt sense of being anchored in the present moment, through practices like deep breathing, body scans, or connecting with the earth beneath our feet. This can help to downregulate the nervous system and prevent us from getting hijacked by stress or overwhelm.

- Titration and pendulation: In body-based therapies, this refers to the process of gently moving between states of activation and settling, challenge and resource, in a way that builds capacity over time. By carefully calibrating our exposure to stressors and regularly returning to a state of grounded presence, we can gradually expand our window of tolerance.

- Co-regulation and healthy attachment: Our capacity for self-regulation is intimately connected with the quality of our close relationships. By cultivating secure, responsive bonds with others – whether friends, family, partners, or therapists – we can develop a greater sense of safety and stability, and borrow from others’ nervous systems to settle and resource our own.

- Self-compassion and acceptance: Learning to meet our own struggles and limitations with kindness, understanding, and patience – rather than harsh self-judgment or denial. This allows us to stay connected with ourselves even in moments of difficulty, and to hold our experience with greater equanimity and grace.

Ultimately, the invitation of the window of tolerance is to befriend the full spectrum of our human experience – not just the pleasant or “positive” states, but the challenging, uncomfortable, and messy ones as well. By learning to ride the waves of activation and settling, expansion and contraction, we can discover a deeper resilience and capacity for presence that’s not dependent on external circumstances.

And as we do this work of self-discovery and self-regulation, we may find that our “window” is not a fixed or static thing, but a dynamic, ever-widening space of possibility. With practice, patience, and care, we can gradually expand our capacity to meet life’s joys and sorrows, challenges and opportunities, with greater ease, openness, and equanimity.

In this way, the window of tolerance becomes not just a concept or a tool, but a way of being in the world – a path of embodied wisdom and compassionate engagement, rooted in the timeless insights of both East and West. By walking this path with curiosity, courage, and care, we can discover a deeper freedom and fullness in the heart of our lived experience, moment by moment, breath by breath.

To work on therapy for sleep in Alabama schedule teletherapy with Pamela Hayes, Kristan Baer, or Haley Beech at Taproot Therapy.

0 Comments