A Review of Into the Abyss by Werner Herzog

Trigger Warning: This essay discusses capital punishment, murder, violence, death, and contains descriptions of violent acts including attempted murder. The film and essay examine traumatic events and their psychological impact on individuals and communities. Reader discretion is advised.

Werner Herzog operates on the principle that perception is reality, and to criticize the perceiver who is deeply watching based on some outmoded collective objectification is foolish bean counting. His documentaries demonstrate this philosophy in action.

A man in his mid-twenties stands next to a pine tree in a Texas park. His baseball cap reads “Pitbull” and he wears a white t-shirt. He explains that the “Bailey” tattoo on his arm will be amended to read “Bailey sucks” if he and the mother of his seventeen-year-old were to break up. Werner Herzog, the director of Into the Abyss, asks him questions about the film’s subject, Michael Perry. Perry is a death row inmate and convicted murderer. The man explains that he didn’t know Perry well, yet Perry had tried unsuccessfully to kill him twice. Both attempts on his life were whims, apparently without animosity on Perry’s part.

The man in the t-shirt explains how Perry had sunk a screwdriver with a two-foot shank into his side beneath his arm. Herzog asks him if he went to the hospital. “No,” the man tells him, “I had to go to work.” The man continues, laughing, “Just some pus and blood come out, got lucky I guess.” He continues “at that time I had not graduated high school or learned to read”.

This is when the conversation changes. Herzog, now seeming bored with questions regarding the subject of the documentary, begins to ask the man in the t-shirt about learning to read in prison. Herzog tells him how proud he should be of this accomplishment and how it will connect him to the world in a new way. The man in the t-shirt relaxes and drops the unconscious defensive posture that he has held for the first part of the interview. He smiles involuntarily for a moment and then beams.

Herzog’s thick accent and mannerisms manage to be both intimate and distant. If a different director was asking these questions to an underemployed, undereducated ex-felon in rural Texas, they might come off as patriarchal or condescending, but Herzog is an alien. His curiosity and sincerity are palpable and his tone is empty of both pity and judgment. While the economic reality of poverty and the effect of privatization on rural areas is never mentioned in the film, it is a constant presence.

Into the Abyss is ostensibly a documentary about the death penalty in America, but what it actually documents is the role that death plays in American life. Few Americans even think about death and even fewer think about the death penalty in their country. Why would we? Thinking about death is not just thinking about the end of a story; it is about thinking about the ultimate unimportance of our own story. American life encourages the belief in self-righteous solipsism just as much as it encourages the belief in immortality.

Michael Perry, the perpetrator of the murder at the center of Into the Abyss, decides, like many Americans have, both that he is the victim of his own story and the center of his own universe. He explains how he is stronger than the inmates who choose to die by suicide before facing the death penalty because he can control his own life by distracting himself. Perry regales Herzog with the important lessons that he has learned in his life, mainly in prison. He explains he is now responsible and accountable because he learned how to listen to instructors when they told him not to get his dry clothes wet at a juvenile offender camp.

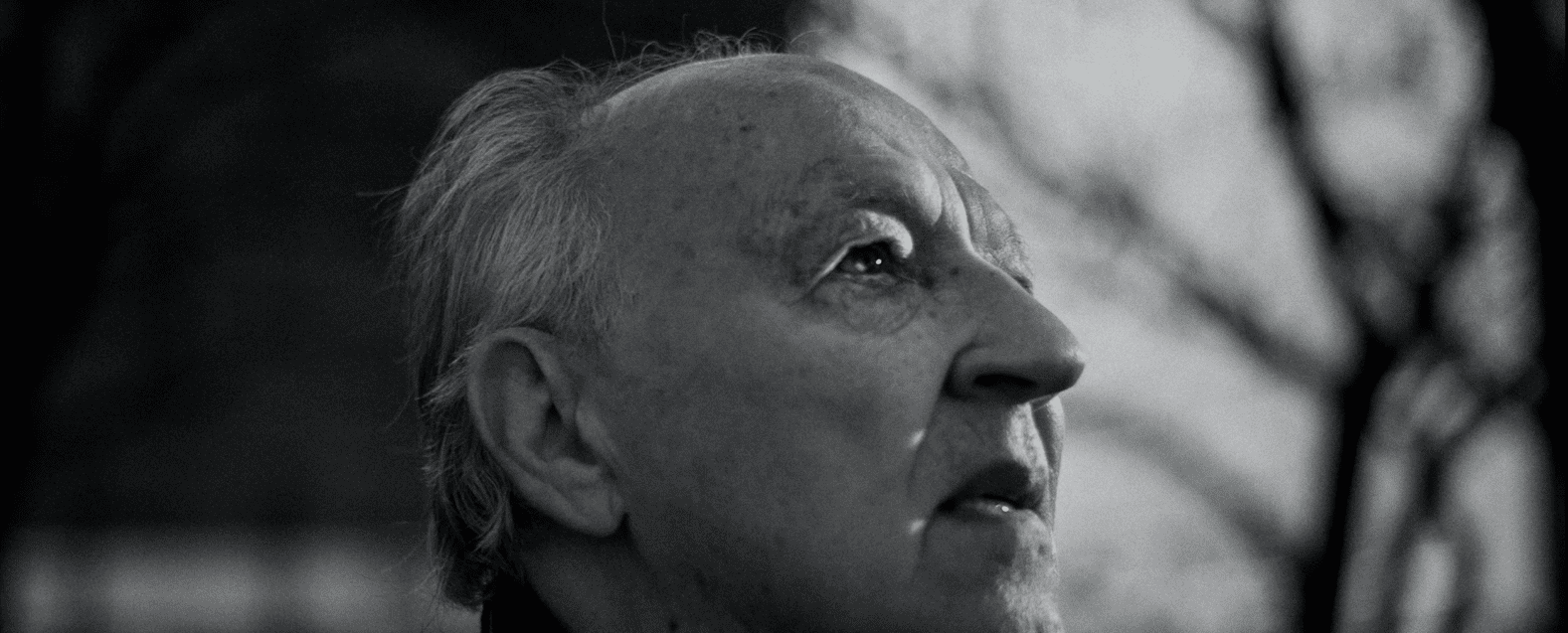

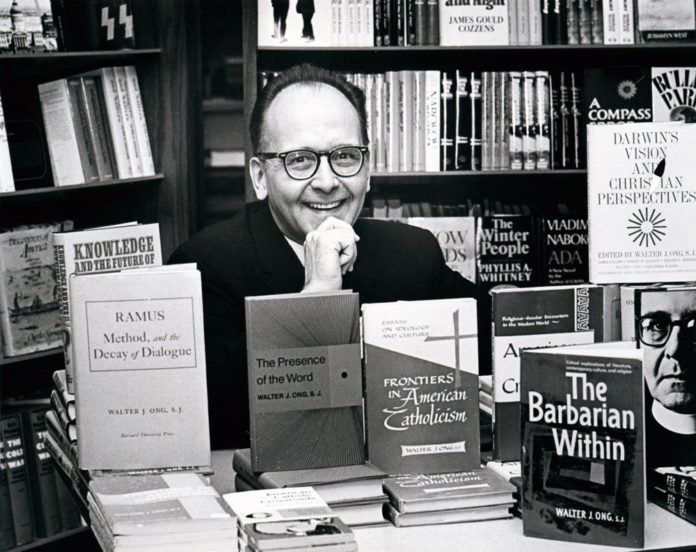

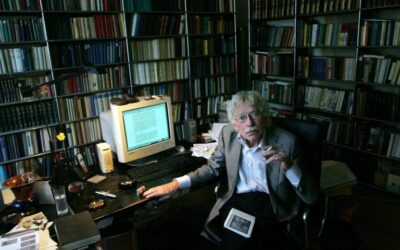

Michael Perry, murderer and subject of into the Abyss

The lesson was important because Perry found it unpleasant to have wet clothes before he learned to listen to authority. Other lessons were lost on Perry. One for example would be that there is a need to be accountable for, or even to acknowledge, a triple murder that he committed on a whim simply to joy ride in a sports car. In prison Michael Perry finds Jesus and explains that God will welcome him to heaven as the victim of a terrible injustice. At his execution he forgives the families of his victims for the “atrocity” they are committing against him. One of the victims’ relatives muses that he was not a monster, but just a child. Lessons that don’t affect Perry are not important. Through a bizarre myopic conversion religion Perry has found a way to make death not affect him either.

In asking America to reflect on its relationship to death Herzog is asking us to consider that maybe even death cannot be a preventative, deterrent, consequence or even a reality to most Americans. I think that Herzog’s take on reality and insanity might be that we are insane when we cannot acknowledge death anymore, especially the death we are partially or wholly responsible for. More so I think that Herzog might be saying that we are all insane. The responsible person just choose what and when are the conditions of our own insanity.

Most of Herzog’s fictional films contain an element of a chthonic off-camera presence that is really what the film is about. In Where the Green Ants Dream, aboriginal people fight encroaching civilization to prevent the awakening of ants who, they believe, dream the world into being. In Aguirre, Wrath of God, a conquistador’s limitless ambition and narcissism lead to him, still monologuing on his own greatness, sinking slowly into the Amazon river. In Fitzcarraldo, a man drives a steamship over a mountain in what might be an unconscious metaphor for Herzog’s inflexible vision for filmmaking. The fact that Herzog insisted the production actually drag a steamboat over a mountain might help to support that interpretation.

Herzog’s documentaries are famous for his digressions that veer wildly off topic but steer his films closer to their more hidden and intended themes. In Lessons of Darkness, Herzog ignores the social and political context of Gulf War footage, reinterpreting it as science fiction about misanthropic aliens that despise the planet and want to wound it. In Cave of Forgotten Dreams, Herzog films albino alligators in a zoo and claims falsely they are a radioactively mutated new species. Herzog’s juxtaposition is likely meant to imply in both films that mankind has no idea where it came from or what it is doing. The fiction Herzog inserts into his factual documentaries also implies that the meaning we make of our own lives might also be a fiction.

Timothy Treadwell is the subject of Herzog’s 2005 documentary Grizzly Man. The film is composed mainly of Treadwell’s own footage of his life with and eventual death by grizzly bears. And yet Herzog makes the film about something else. During one of Treadwell’s grandiose and dissociated rants about himself and his own importance to the wild animals he follows, Herzog sighs deeply and then takes the film in a different direction.

Herzog crops Treadwell’s footage until Treadwell is out of frame and speaks over him. Herzog’s narration asks the audience to appreciate the beauty inherent in the scenery around Treadwell. Bored with his subject, Herzog points the audience away from his documentary subject’s internal reality. The change in perspective is subtle but jarring to watch. His technique reminds the viewer immediately how insane Treadwell has become.

Insanity is a word that Herzog claims to be unable to define, yet insanity might be the strongest through line in the topics of his documentaries. Each of his subjects displays some different shade of insanity. In Encounters at the End of the World, Herzog asks a penguin biologist if penguins can be insane. The biologist tells him that, no, penguins are animals, and therefore interested only in reproducing and preserving their own lives.

Even though he cannot define the word insane, Herzog’s career proves that he is well able to locate insanity, whatever it is. Herzog does not leave Antarctica until he finds an insane penguin. He wades through a sea of thousands of penguins until he finds a lone penguin seemingly uninterested in reproducing or self-preservation. Herzog watches as the creature starves, throwing itself up a mountain while its peers migrate north to feed and reproduce.

If he is looking for insanity then in Into the Abyss Herzog may have found his perfect subject, however the viewer is left with only a vague idea of who the subject of his film is. Michael Perry and his co-conspirators in murder are not quite the film’s focus, nor are the death row groupies who marry and bear the children of death row inmates. The subject is not even the victims’ or perpetrators’ family members who expound on the forces that create murder and the permanent effect it has on the world.

Michael Perry never becomes a being that can empathize with the experience of others or understand the human cost that his actions took on the world. Because of Michael Perry’s decision to murder in a personal and public way, the system that he resides in has deemed his life forfeit. Many in America might see Perry’s execution as a sort of justice but Herzog’s film seems to wonder both who benefits from Perry’s death and why the system that created Perry is not indicted.

To many it might seem like common sense to kill a murderer, especially one as unrepentant and self-righteous as Perry. Into the Abyss examines the effect of Perry’s execution on all members of his and his victims’ families. It also explores the effect the death penalty has on all the people required to carry it out. Herzog says the film has no thesis about whether or not there should be a death penalty, but it is hard to find any good that comes from pushing Perry into the abyss of death behind his victims.

In Herzog’s last interview with Perry, Perry very much seems like a child. Briefly angry, Perry adds “the state of Texas wants to murder me.” Perry politely defers to Herzog’s authority, calling him “sir” and explaining to Herzog what it means to “be a man.” Perry seems unable in his last interview to even understand what death is when he talks about his own impending death, then only eight days away at the time. “I don’t know if it will happen. I can’t imagine it happening,” he tells Herzog. Perry then continues, “I can’t imagine laying on the gurney dead, but if it happens then I will have to deal with it.” Whatever Perry thinks he will have to deal with at that point the audience is left to wonder.

Herzog is able to slip into the scenes of his documentaries like a specter. Herzog’s questions have a grounding effect on his subjects. His subjects seem to be connected to something truer and deeper than their life usually affords. Herzog drops past his subjects’ defenses and extracts answers that even his subjects seem to be unaware they possessed minutes before. Herzog talks very little, but mostly just watches his subjects, and his curious watching is what allows his documentary process to work.

In one interview from Into the Abyss, Herzog interviews a death row chaplain. The man has sat with countless men while they died. The chaplain talks about how much he likes golf. He describes how much he enjoys driving the cart as a part of golf. He describes how it relaxes him to watch animals in the woods and trees. And then, finally, he gets to how one time he braked his cart just in time to spare a squirrel’s life. The chaplain cries about how many people he has knelt beside while they died for a death he could not prevent. He laments the choices that led them to that execution. He laments that while he could stop the wheels of a cart, he could not stop the wheels of state that killed the men that he sat with. Herzog watches the interview.

Into the Abyss is ostensibly a documentary about the death penalty in America, but what it actually is a documentary about the role that death plays in American life. Few Americans even think about death and even fewer think about the death penalty in their country. Why would we? Americans pretend to be both immortal and exceptional. The ability to feel empathy and the ability to acknowledge our own finitude are directly correlated. Or, put another way, our ability to feel that another person’s storyline is important bears a direct relation to our ability to acknowledge the unimportance of our own.

It is when systems disconnect us from meaningful interactions with each other that we are at our most dangerous. We never see the trauma that affects the victims’ families the way we are told about the trauma of Perry’s childhood and adult life. One victim’s sister stays out of the media spotlight because she is not looking for coverage, yet her pain echoes through the film. The execution did not deter anything. A surface level glance would reveal the truth.

Closest to the film’s emotional center are the people who become the cogs and gears in the state’s process of enforcing the death penalty. The prison guard who quit describes realizing that he had become a murderer, however sanctioned by the state. He is describing what it means to be a man in a system that makes you less than human. The rainbow he reports seeing after an execution proves nothing and everything at once.

Yet still there is a madness lurking here. Despite the film’s ostensible lack of a clear subject, viewers are left with a powerful idea of what insanity is. Herzog is correct, the word insanity lacks a definition. However, viewers of Into the Abyss feel the presence of something deeply wrong, not just in Perry’s actions but in the system’s response.

During the last interview one gets the sense that it is the insanity of this system that murders murderers but refuses to change or even admit any of the realities that cause crimes to happen and people like Michael Perry to exist. Michael Perry forgives them delusionally. “Nobody has a right to take a human life,” says one family member. “It’s so easy to change the law,” says another, but nothing changes.

Perry’s father is also an inmate in the same facility as Perry. The cycle continues. Perry is just a boy in many ways. In the same way that Michael Perry talks about his delusions, neither does the country that murders through imperialism and lack of healthcare ever understand what it does. By design it is someone else’s fault for doing so and so or not voting in some other way. There are people like the death row groupies that project onto the inmates their own need for connection in a disconnected world. Herzog follows several death row inmates that have girlfriends and wives who project the perfect man on a man sitting on death row.

When we cannot acknowledge a quality as a part of us we project it. Herzog doesn’t change or mature as a film maker as a seeming point of pride; he applies one lens unflinchingly. People who are pretending to live in a different world that they actually do are insane but also it is insane to think that any of us can understand how the world actually works. Us sane people are stuck in this double bind. “I don’t pay attention to these walls, I don’t focus on it,” Perry says from death row. America bombs, stages coups, and ignores the thousands that die here from preventable causes. To the extent that America even notices these things, a marginal majority approve of them. The minority that disapproves doesn’t seem to be very loud or at least not very represented in our own pop culture.

A culture’s relationship with death is what defines that culture. The death penalty is our tacit agreement on what actions merit the ending of human life.

In Into the Abyss Herzog’s interview style becomes one of those coin funnels in the front of museum entrances. Honesty, respect, dignity, and consistency. Give people something valuable like a bit of yourself and it will orbit inevitably back to a piece of themselves if you just give them time. Maybe that is a good formula for life not just for interviews. It is definitely not the attitude of America’s criminal justice system.

Herzog is an observer. One of the film’s most affecting interviews is with Fred Allen, a former captain on the death row “tie-down team” who participated in over 120 executions before quitting. Allen strapped condemned inmates to the gurney for their executions until something broke in him. After the execution of Karla Faye Tucker in 1998, Allen could no longer continue. He gave up his career and pension to walk away from the death machine.

In their conversation, Allen describes his breakdown – how he started shaking uncontrollably, how he couldn’t eat or sleep, how his body finally rebelled against what he had been doing. Herzog asks him about finding his “true self,” and Allen, this tough Texan who spent years executing people, begins to cry. He talks about realizing he had become a murderer, state-sanctioned or not.

“Do you think your true self came forward?” Again a different interviewer might be threatening to the Texan. Herzog sits with a man who refused to watch, despite his mantra. Perhaps it was the act of refusing to participate that was the most profound poetry. The ultimate irony that the man whose documentary style is watching as a form of participation seems to agree that refusing to watch this system is the ultimate act of grace and to avert one’s gaze may be the most profound resistance.

Herzog’s relationship to death, movies, pop, culture is strange. Some times he talks about them like they are the ultimate concern. Other times they are mere trifles. At a Red Carpet event for Disney’s the Mandalorian Herzog was asked if he was excited to be in a Star Wars film. “I have never seen Star Wars” Herzog replies. Asked if he was excited to be in a John Favreau film he replies “I have never seen his movies”. “What do you watch” the interviewer finally asks and Herzog turns somber. Herzog explains to the baffled press pool that he watches the Kardashians because even though it creates psychic suffering, the real artist must never avert their gaze. I agree with Herzog that the participants and the viewers of American reality TV do suffer psychic damage. I think that it is bizarre that Herzog assumes that this is self evident knowledge that everyone else in America is aware of.

Herzog seems to think the psychic suffering caused by the Kardashians walking the red carpet is a better lesson in humanity than learning from the most popular films ever made. The poet must not avert his gaze. Looking beneath the surface is why this looking for a point other than the point of his movies is what makes them so powerful and so easy to miss the message of on the surface. His films work on a surface level but also open once one dips beneath the surface and begins to try to see what Herzog sees. Into the Abyss works because you get the feeling that Herzog does not understand what it is that he is seeing.

Michael Perry decides like many Americans have that the world revolves around him and he is the victim of his own story. We deny death by creation or by neurosis. Death is horrifying sure. Irvin Yalom calls thinking about death staring into the sun, but death presupposes that we are alive and this is the domain of Herzog.

Herzog has called The Act of Killing one of the most important films of our time. This documentary, which he executive produced, ends in a dry heave. Anwar Congo, one of the perpetrators of the Indonesian mass killings, physically retches on a rooftop – his body violently rebelling against what it has done while he has dissociated himself into a nonchalant personality for decades.

Into the Abyss is one of the most effective works of art about death. It accomplishes this largely by refusing to explain itself.

When podcaster Marc Maron asked Herzog changing his calling from becoming a priest to a filmmaker Maron offers the interpretation that movies became a higher calling. “No,” Herzog tells Maron “That is not right and I will not explain”.

Herzog is an observer. Looking beneath the surface is why this looking for a point other than the point of his movies is what makes them so powerful and so easy to miss the message of on the surface. His films work on a surface level but also open once one dips beneath the surface and begins to try to see what Herzog sees. Into the Abyss works because you get the feeling that Herzog does not understand what it is that he is seeing.

Herzog has made dismissive comments about Jung and hipsters, yet the point is that you get it, not what it is. Herzog’s obsession has always been the forces that move things that people don’t see. His lens is never looking at the thing that his camera lens is on but on the forces beneath it. His interests are chthonic. Always looking for the thing beneath the thing.

Where most high art directors either go mainstream or peer further and further inward, Herzog has done neither. He applies a consistent, determined, and unyielding lens to the world. That has not made him rich or well known in the way mainstream directors are. Werner Herzog is a weird guy known in film circles for his uncompromising vision.

The ability to feel empathy and the ability to acknowledge our own finitude are directly correlated. Or, put another way, our ability to feel attached to feel that another person’s storyline is important bears a direct relation to our ability to acknowledge the unimportance of our own.

At the same time Herzog zeroes in on some forces, he ignores others.

Why Herzog Matters to Psychotherapy

For existential and Jungian therapists alike, Herzog’s work presents a paradox that perfectly embodies our field’s central tensions. Herzog likes Wagner, seems to hate psychotherapy and Jung based on comments he makes, yet often proves the Jungian therapist’s point with his work. He has dismissed therapy as navel gazing and called Jung’s ideas “New Age nonsense,” yet his films consistently explore the shadow, the collective unconscious, and the archetypal patterns that Jung spent his life mapping.

Herzog is interested in how psychotic the supposedly sane humans are but disinterested in psychosis itself. He doesn’t want to diagnose or cure; he wants to witness. This makes his work invaluable to therapists precisely because he approaches the human condition without our professional lens, yet arrives at similar truths.

From an existential perspective, Herzog’s films are meditations on authenticity, death anxiety, freedom, isolation, and meaninglessness. Every subject he chooses confronts these ultimate concerns. Michael Perry cannot face his own mortality or the mortality of others. The death row chaplain confronts the absurdity of comforting the condemned. The former executioner faces his radical freedom to simply stop participating. These are textbook existential crises, yet Herzog never names them as such.

From a Jungian perspective, Herzog’s work is pure shadow work made visible. Into the Abyss shows us the shadow of American culture: our projected violence, our denial of death, our inability to integrate the destructive aspects of our nature. The death penalty becomes a ritual of shadow projection where we locate all evil in the condemned and execute them to maintain our innocence. Herzog makes us look at what Jung would call the collective shadow, the parts of our cultural psyche we refuse to acknowledge.

Herzog seems to speak the language of nihilism and existentialism but not as a nihilist or as an existentialist but as a profound romantic. This is what makes his work so powerful for therapists. He wants us to get along and love each other, a point he finds self evident, BUT he won’t let us look away from ANY horror that exists before we do. This is therapeutic work at its core: the insistence that authentic connection and love are only possible when we stop denying the darkness.

That is why some love him and some hate him, calling him an obscurantist and a nihilist. He is neither. He just may be one of the most earnest romantics in existence. He thinks we have to look at the shadow, the horror, before we could ever earnestly and authentically believe in humanism. It’s quite a paradoxical conundrum that mirrors the therapeutic process itself.

His work can be approached from an existential lens or a Jungian mystical one and it holds up equally under either gaze. His profound truths about humans and how they make meaning remain valid no matter how nihilistic or how silly those truths get at the same time. A penguin walking toward certain death in Antarctica becomes simultaneously absurd, tragic, and deeply meaningful. A death row inmate’s delusions become both pathetic and profoundly human.

For therapists, Herzog offers something invaluable: a way of witnessing human suffering and madness without pathologizing it, without trying to fix it, without even fully understanding it. His camera becomes like the therapeutic space itself, a container where the unspeakable can be spoken, where the shadow can emerge, where meaning can be made from meaninglessness.

Herzog refuses to provide the comfort of diagnosis or the distance of theory. He makes us sit with the discomfort of not knowing, of witnessing without judging, of holding paradox without resolution. This is perhaps why he dismisses psychotherapy while embodying its deepest principles. He doesn’t want to analyze the shadow; he wants to film it. He doesn’t want to interpret dreams; he wants to show us we’re already living in one.

In the end, Herzog’s romanticism and his insistence on looking at horror are not contradictory but complementary. Like the best therapy, his films suggest that love and connection are possible not in spite of our darkness but because we’ve learned to face it together. Into the Abyss doesn’t tell us whether the death penalty is right or wrong. It does something more radical: it makes us sit with the full weight of what we do to each other, and then asks us if we can still find a way to be human together.

For those of us in the helping professions, Herzog reminds us that sometimes the most therapeutic thing is not to interpret or analyze or cure, but simply to witness with full presence and radical curiosity. To ask the unexpected question. To notice the squirrel that was saved while the men could not be. To see both the delusion and the humanity in the same frame. This is the work, whether we call it existential, Jungian, or simply human.

On the Nature of Evil and Avoidance

Perhaps evil is what Jung and others always told us it was. Look at Michael Perry in Into the Abyss. He murdered three people for a sports car. Not for survival, not for revenge, not even for money really, but for the temporary experience of driving something shiny and fast. Maybe evil is avoidance. Avoidance of our own authentic journey, avoidance of empathy, of growth, of finding meaning through things other than consumption.

Perry couldn’t face his own emptiness, so he filled it with other people’s terror and a stolen car. He couldn’t do the hard work of becoming, so he took shortcuts through other people’s lives. This is evil as Jung understood it: the refusal to individuate, the rejection of consciousness, the desperate clinging to unconsciousness even when it destroys everything around us.

Maybe we are geared to this avoidance. Maybe the bureaucracies and hierarchies that we have built are the best way to hide from that part of ourselves our ego wants us to be out of touch with. The prison system, the court system, the execution chamber itself, all these elaborate structures that allow us to kill without any individual feeling like a killer. The chaplain didn’t kill anyone. The guard didn’t kill anyone. The warden didn’t kill anyone. The system killed someone. Perfect avoidance.

These bureaucracies, hierarchies, and structures ignore intuition by design. They are built to disconnect us from our felt sense of right and wrong, from our embodied knowledge of what it means to take a life. They cut us off from our humanity by making us into functions, roles, job descriptions. The man who straps the condemned to the gurney doesn’t insert the needle. The man who inserts the needle doesn’t push the plunger. The man who pushes the plunger doesn’t make the law. Everyone avoids. Everyone can sleep at night.

Maybe when Herzog critiques these things in psychotherapy, even as a critic, psychotherapists should listen to him. After all, what have those structures done to psychotherapy? How many of us have become cogs in the insurance machine, filling out forms, meeting productivity standards, diagnosing for billing codes rather than understanding? How many therapeutic encounters have been reduced to manualized treatments, evidence-based protocols that work on paper but miss the soul entirely?

Herzog sees what we sometimes cannot see from inside our own profession: that the very structures meant to help us help others can become ways of avoiding genuine encounter. The DSM becomes a wall between us and our clients. The treatment plan becomes a map that keeps us from exploring the actual territory. The fifty-minute hour becomes a boundary that protects us from the full weight of another’s suffering.

Perry avoided his authentic journey by stealing and killing. The state avoids its authentic reckoning by executing him through a complex bureaucracy. And we, perhaps, avoid our own authentic encounter with human darkness by turning it into pathology, into something to be treated rather than witnessed.

Herzog’s critique stings because it’s accurate. We have built structures that allow us to seem like we’re engaging with the depths while actually skating on the surface. We talk about the unconscious without diving into it. We discuss trauma without feeling it in our bodies. We name the shadow without walking into the darkness.

The man in the t-shirt who got stabbed with a screwdriver and went to work anyway understands something about evil that all our theories might miss. Evil is banal. It happens on a Tuesday. It doesn’t announce itself with dramatic music. It’s a boy who can’t feel anything trying to feel something by taking everything from someone else. It’s a system that responds to meaningless death with methodical death. It’s all of us looking away, filing our papers, following our protocols, avoiding the terrible truth that we are all capable of becoming Michael Perry, or worse, becoming the machine that executes him.

Herzog forces us to look. Not to analyze, not to diagnose, not to cure, but just to see. And in that seeing, perhaps, lies the beginning of whatever healing is possible. Not healing as the absence of wounds, but healing as the integration of our woundedness into our wholeness. Not healing as the elimination of evil, but healing as the courage to face it, in ourselves, in our systems, in our world, without looking away.

This is what Herzog offers psychotherapy: a mirror that shows us our own avoidance, our own complicity in the structures that dehumanize even as they claim to help. And perhaps, if we can bear to look, we might find our way back to what therapy was always meant to be: one human being present with another in their darkness, without judgment, without easy answers, without looking away.

0 Comments