What is Metamodernism?

The concept of metamodernism has emerged as a paradigm to describe the cultural, philosophical, and therapeutic landscape after postmodernism. While there is no single agreed-upon definition, metamodernism broadly refers to a structure of feeling and mode of discourse that oscillates between aspects of modernism and postmodernism. It seeks to reincorporate depth, affect, spirituality, and grand narratives after the deconstructions of the postmodern, while retaining postmodernism’s insights around difference, contextualism, and the constructedness of reality.

Metamodernism is an emerging cultural paradigm that seeks to transcend the dichotomies of modernism and postmodernism. As a relatively new concept, there are various ways of understanding and defining metamodernism. This paper will explore ten different perspectives on conceptualizing metamodernism, showcasing the diversity of thought surrounding this topic.

1. Oscillation Between Modernism and Postmodernism

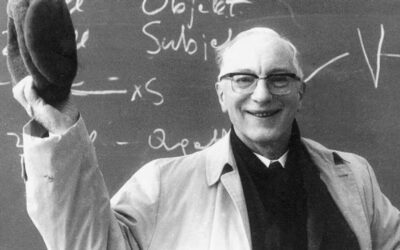

One of the most prominent perspectives, put forth by Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker, views metamodernism as an oscillation between modernist and postmodernist sensibilities. They argue that metamodernism is characterized by a constant shifting between sincerity and irony, enthusiasm and skepticism, hope and melancholy.

This oscillation allows for a more nuanced and flexible approach to meaning-making, one that acknowledges the limitations of both modernist grand narratives and postmodernist deconstruction. By embracing the tension between these poles, metamodernism seeks to navigate the complexities of our time with a sense of informed naivety and pragmatic idealism.

2. Reconstruction of Meaning

Another perspective, championed by Seth Abramson, sees metamodernism as an attempt to reconstruct meaning and purpose after the deconstructions of postmodernism. This view emphasizes the return of depth, affect, and grand narratives, albeit in a more self-aware and pluralistic manner.

Abramson argues that metamodernism seeks to reintegrate the emotional, spiritual, and mythical dimensions of human experience that were marginalized by postmodernism’s emphasis on irony and relativism. At the same time, it acknowledges the need for multiple, coexisting narratives rather than a single, totalizing metanarrative.

3. Dialogic and Participatory Epistemology

The participatory poetics perspective, as outlined in the article “The Participatory Poetics of Metamodern Language and Culture,” proposes a dialogic and participatory epistemology. In this view, meaning emerges through the co-creative interplay of language, affect, and experience, blurring the boundaries between author and audience, fact and fiction.

This perspective highlights the role of digital media and participatory culture in shaping metamodern sensibilities. It suggests that the interactive, immersive, and improvisational nature of online communication has given rise to new forms of collective sense-making and worldbuilding.

By emphasizing the performative and embodied dimensions of language, the participatory poetics approach challenges the modernist notion of objective, disembodied knowledge. Instead, it sees meaning as something that is actively constructed and negotiated through social interaction and creative play.

4. Synthesis of Opposing Polarities

Hanzi Freinacht’s perspective on metamodernism emphasizes the synthesis of seemingly opposing polarities, such as mind and matter, science and spirituality, reason and emotion. This view seeks to integrate the best aspects of various worldviews and developmental stages into a more comprehensive and inclusive framework.

Freinacht argues that metamodernism represents a higher stage of psychological and cultural development, one that transcends the limitations of both modernist reductionism and postmodernist relativism. By embracing paradox and complexity, metamodernism aims to create a more holistic and integral worldview.

This perspective draws on the work of integral theorists like Ken Wilber, who see human development as a process of increasing complexity and integration. Freinacht suggests that metamodernism is the next stage in this evolution, one that can help us address the global challenges of the 21st century.

5. Hypermodernity and Digimodernism

Some thinkers, such as Gilles Lipovetsky and Alan Kirby, frame metamodernism as an intensification of modernity, rather than a distinct paradigm. Lipovetsky’s concept of hypermodernity and Kirby’s notion of digimodernism highlight the accelerating pace of technological change and its impact on culture and subjectivity.

Hypermodernity, according to Lipovetsky, is characterized by hyper-consumption, hyper-individualism, and hyper-reflexivity. It represents a radicalization of modernist values like progress, autonomy, and innovation, leading to a state of constant flux and uncertainty.

Digimodernism, as defined by Kirby, emphasizes the transformative impact of digital technologies on cultural production and consumption. It suggests that the participatory, interactive, and immersive nature of digital media has given rise to new forms of subjectivity and sociality.

6. Post-Postmodernism and the New Sincerity

Another perspective situates metamodernism as a post-postmodern sensibility, characterized by a renewed emphasis on sincerity, authenticity, and emotional engagement. This view, associated with figures like David Foster Wallace and Wes Anderson, seeks to move beyond the ironic detachment and cynicism of postmodernism.

The New Sincerity, as it has been called, represents a yearning for genuine connection and meaning in a world saturated with simulation and spectacle. It acknowledges the impossibility of pure authenticity, but nevertheless strives for a more honest and vulnerable form of self-expression.

This perspective is exemplified by the work of David Foster Wallace, whose essays and novels grapple with the challenges of living a meaningful life in an age of irony and information overload. It is also evident in the films of Wes Anderson, which balance quirky humor with sincere emotion and a sense of nostalgia for lost innocence.

7. Alter-Modernism and the Global South

The alter-modernist perspective, proposed by Nicolas Bourriaud, frames metamodernism as a pluralistic and decentered modernism that emerges from the global South and other marginalized contexts. This view emphasizes the need to decolonize and diversify the narratives of modernity and progress.

Bourriaud argues that alter-modernism represents a shift away from the Western-centric, universalist notions of modernity towards a more heterogeneous and inclusive vision. It acknowledges the multiple modernities that have emerged in different parts of the world, each with its own unique cultural and historical context.

This perspective highlights the importance of cultural diversity and intercultural dialogue in shaping the future of global society. It suggests that metamodernism must be attentive to the voices and experiences of marginalized communities, and work towards a more equitable and sustainable world order.

8. Cosmodernism and the Anthropocene

Christian Moraru’s concept of cosmodernism situates metamodernism within the context of the Anthropocene and the planetary challenges of the 21st century. This perspective highlights the need for a new, more expansive humanism that can grapple with the ecological, technological, and existential risks of our time.

Cosmodernism, according to Moraru, represents a shift towards a more ecological and relational understanding of the human condition. It acknowledges the deep interconnectedness of human and nonhuman life, and the urgent need for a more sustainable and resilient future.

This perspective draws on the insights of systems thinking, complexity theory, and the environmental humanities to develop a more holistic and integrative approach to global challenges. It suggests that metamodernism must be grounded in a sense of planetary stewardship and responsibility.

9. Metamodern Politics and Activism

Another perspective focuses on the political and activist dimensions of metamodernism, as exemplified by movements like Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, and Extinction Rebellion. This view emphasizes the need for new forms of collective action and social imagination that can challenge the status quo and catalyze systemic change.

Metamodern activism, according to this perspective, is characterized by a pragmatic idealism that combines utopian vision with strategic realism. It seeks to build broad-based coalitions and movements that can mobilize people around shared values and goals, while also acknowledging the complexity and diversity of social struggles.

This perspective highlights the importance of prefigurative politics, or the practice of embodying the change one wishes to see in the world. It suggests that metamodernism must be rooted in a sense of empathy, solidarity, and collective empowerment.

10. Integral Theory and Metamodernism

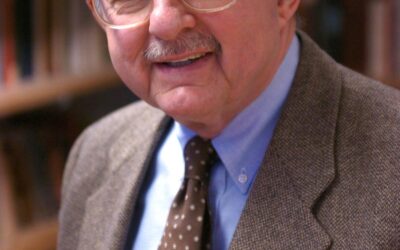

Finally, some thinkers, such as Ken Wilber and Hanzi Freinacht, frame metamodernism within the context of integral theory and developmental psychology. This perspective sees metamodernism as a higher stage of cognitive, emotional, and spiritual development that integrates and transcends previous stages.

Integral theory, as developed by Wilber and others, provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the evolution of consciousness and culture. It suggests that human development proceeds through a series of stages, each building upon and integrating the insights of the previous ones.

Freinacht argues that metamodernism represents the emergence of a new stage of development, one that can integrate the best aspects of modernity and postmodernity while also transcending their limitations. This stage is characterized by a more holistic and integrative worldview, a sense of global solidarity and responsibility, and a commitment to personal and collective transformation.

Key Facets of Metamodernism

Some of the key facets proposed by various thinkers include:

- Oscillation between modern and postmodern attitudes: Metamodernism is characterized by a pendulum swinging between “naive” modernist enthusiasm and ideals, and postmodern irony, detachment and skepticism (Timotheus Vermeulen)

- “Informed naivety” and “pragmatic idealism”: Engaging sincerely with ideals like love, hope, and faith while maintaining an ironic distance. A romantic reaction to and against the postmodern. (Vermeulen & van der Akker)

- Return to depth, affect, ontology: Reengaging with notions of essence, universality, depth, spirituality after poststructuralism – a “structure of feeling” based more on intensities than surfaces. (Seth Abramson)

- Narrative reconstruction: Rebuilding shared stories, myths, and meanings to orient and ground us after postmodern relativism and fragmentation, while avoiding naive metanarratives. (Brendan Dempsey)

- Embracing paradox and “both/and”: Seeking to move beyond deconstruction and irony towards reconstructions that incorporate contradiction – “transcending irony with sincerity”. Metamodernism seeks a “both-and” rather than “either-or” approach. (Hanzi Freinacht)

Post-Secularism and Re-enchantment

Related to metamodernism is the notion of post-secularism – a turn back towards questions of spirituality, meaning, and re-enchantment. As John Caputo argues, religion and spiritual longing persist after secularization, as people seek existential meaning and ways to navigate suffering. Post-secular philosophers like Caputo, Gianni Vattimo and Christopher Partridge advocate for a non-dogmatic “weak theology” or “occulture” that embraces spiritual pluralism, the “return of religion”, and re-enchantment.

Implications for Psychotherapy

Metamodernism and post-secularism have significant implications for how we conceptualize subjectivity, psychotherapy, and healing:

- Depth psychology: Metamodernism points towards a renewed engagement with both Freudian and Jungian approaches – the “archaeological” mining of individual/collective unconscious and the “teleological” orientation towards wholeness, meaning, spiritual yearning.

- Beyond deconstruction: Postmodern therapies tend to focus on deconstructing the client’s self-narrative and revealing how it is shaped by cultural discourses. Metamodern therapy, while retaining this critical insight, also seeks to help the client reconstruct a more expansive, meaning-providing narrative to orient their subjectivity.

- Dialogical and emancipatory: Drawing on philosophers like Jürgen Habermas, metamodern therapy aims to be a dialogical encounter between client and therapist, rather than a top-down imposition of “expert knowledge”. The goal is facilitating emancipatory self-understanding for the client.

- Engaging the spiritual and transpersonal: Metamodern therapy takes the client’s spiritual and existential concerns seriously, drawing on transpersonal psychology’s expanded cartography of consciousness. It seeks a “post-secular spirituality” that is exploratory and non-dogmatic.

- Working with paradox and the unknown: Influenced by psychoanalytic thinkers like Wilfred Bion, metamodern therapy aims to help the client tolerate uncertainty, paradox, and the unknown – key capacities needed to navigate the complexities of postmodern life.

0 Comments