A Guide for Immanentizing the Eschaton in Therapy

Why a Dead German Philosopher Matters for Your Therapy Practice

Picture this: You’re sitting with a client who can’t stop talking about how “the system is rigged,” or maybe they’re convinced that if only we could implement the perfect political solution, all our problems would disappear. Sound familiar? Whether it’s QAnon believers, market fundamentalists convinced that pure capitalism will save us all, or activists certain that their ideology holds the key to human salvation, we’re swimming in what Eric Voegelin would have called “gnostic” thinking.

And here’s why that matters for therapy.

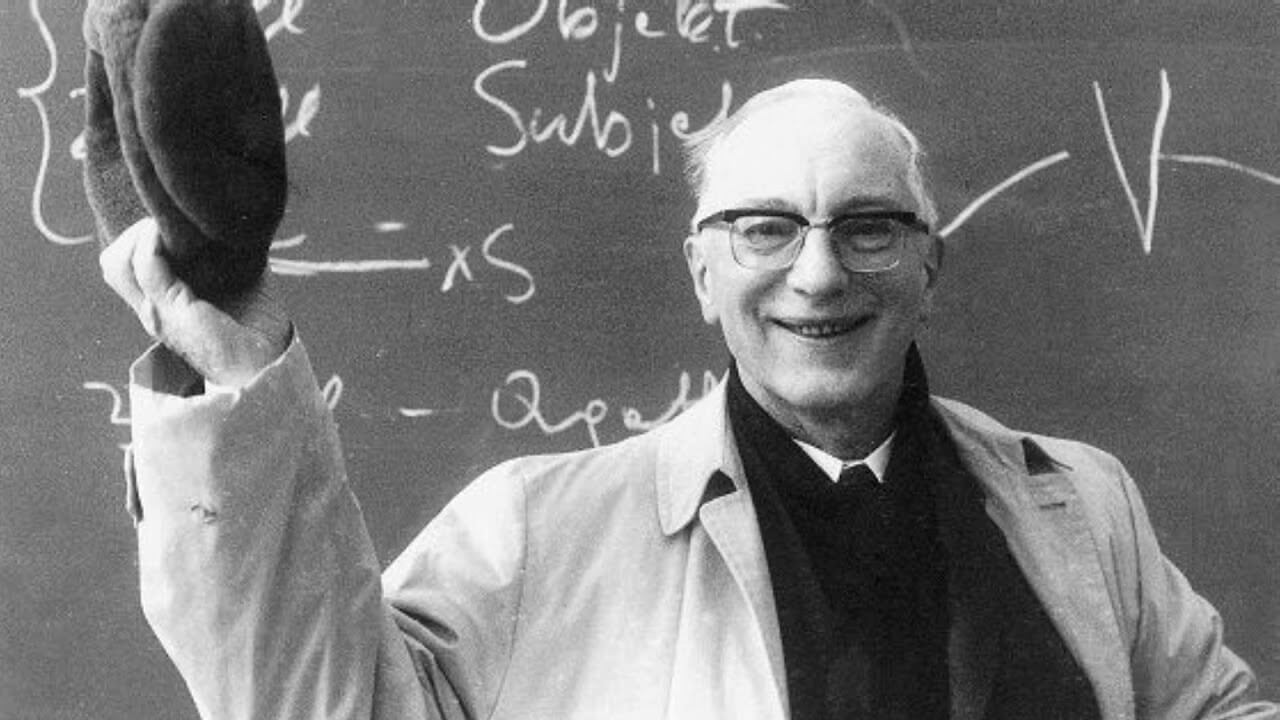

Eric Voegelin (1901-1985) was a philosopher who fled Nazi Germany and spent his life trying to understand how seemingly rational people could fall under the spell of totalitarian ideologies. What he discovered has profound implications for how we understand trauma, healing, and the human search for meaning in our therapeutic work today.

The Gnostic Personality: When Knowledge Becomes a Drug

Voegelin noticed something fascinating: throughout history, certain people have claimed to possess secret knowledge (gnosis) that, if properly applied, could transform the world into paradise. The ancient Gnostics believed the material world was evil and that special knowledge could liberate the soul. Modern political movements, Voegelin argued, follow the same pattern – they just swap out spiritual salvation for political transformation.

Think about it. How many of your clients are absolutely certain that if only:

- The right party would win

- The markets were truly free

- Their conspiracy theory was exposed

- Their ex would just understand

- The World could see a video of what the abuser did

- They could have objective proof that they have a right to call what happened trauma

…then everything would be perfect?

This is gnostic thinking in action. It’s the belief that there’s a magic key that will unlock the door to a problem-free existence. And spoiler alert: there isn’t one.

January 6th Through Voegelin’s Eyes

Let’s get specific. The January 6th Capitol siege wasn’t just a political event – it was a massive outbreak of what Voegelin called “pneumopathology” (literally, “spiritual sickness”). But here’s what’s crucial to understand: this happened against a backdrop where traditional institutions – churches, universities, political parties, civic organizations – had lost their credibility with large swaths of the population. When people no longer trust the containers that once held meaning, they become desperate for new sources of power and transformation.

The participants weren’t just angry about an election; they were possessed by a gnostic vision where the world divides into true patriots versus the deep state, where they alone possessed secret knowledge about the “real” truth, where apocalyptic transformation was imminent, and where violence became justified because they were fighting absolute evil. This is exactly what happens when institutional authority collapses – people turn inward, seeking personal gnosis, magical thinking, and messianic figures who promise to restore their agency through dramatic action.

Contemporary philosophers like Peter Sloterdijk and David Tacey are tracking these same forces through different lenses. Sloterdijk writes about the “spherological” crisis of modernity – how the protective bubbles of meaning that once surrounded us have burst, leaving us exposed and desperate for new forms of immunity. Tacey explores what he calls the “post-secular sacred” – the way spiritual energies that once flowed through traditional religious channels now surge through politics, wellness movements, and conspiracy theories. They’re describing what we might call the metamodern condition: neither purely modern nor postmodern, but something new that combines sincere belief with ironic distance, magical thinking with technological sophistication.

The Market as Savior: Another Gnostic Dream

But it’s not just the political right. Voegelin would have had a field day with market fundamentalism – the belief that unregulated capitalism will solve all human problems. This too emerges from the collapse of traditional authorities. When neither church nor state seems capable of delivering prosperity or meaning, the market becomes a mystical force with its own hidden hand that possesses knowledge beyond human understanding. Salvation comes through profit, successful entrepreneurs become the new elect who understand sacred economic laws, and anyone who questions the market gets labeled as economically illiterate.

We see this in clients who tie their entire self-worth to financial success, who believe that the next business venture or investment strategy will finally bring them happiness. It’s the same gnostic pattern, just dressed in a business suit. And like all gnostic movements, it promises to restore agency – “You too can be a millionaire!” – while actually encouraging people to surrender their agency to market forces beyond their control.

Historical Patterns: When the Center Cannot Hold

This isn’t new. History shows us that whenever established institutions lose their grip on meaning, gnostic and magical movements rush in to fill the void. Consider the Mithraic mystery cults that spread through the Roman legions in the second and third centuries CE. As the traditional Roman civic religion lost its power to inspire, soldiers turned to Mithras, the Persian god who promised secret initiation, cosmic struggle, and personal transformation. The cult offered what the state religion couldn’t: direct experience of the divine, brotherhood across social classes, and the promise that individual spiritual achievement could transcend earthly powerlessness.

Early Christianity itself emerged in this context, spreading first among slaves, women, and the marginalized – those with the least investment in existing power structures. When you have no earthly power, the promise of spiritual power becomes irresistible. The early Christians weren’t just believing in ideas; they were experiencing what they understood as direct contact with the divine, speaking in tongues, prophesying, healing. Their gnosis wasn’t theoretical – it was experiential, ecstatic, transformative.

Fast forward to the 1970s. The oil embargo, Vietnam, Watergate – traditional American confidence was shaken. What emerged? An explosion of New Age mysticism, from EST to astrology to crystals to channeling. When external power fails – when you can’t fill your gas tank, when your government lies to you, when your economy staggers – people turn inward. They seek personal transformation, hidden knowledge, direct spiritual experience. The Human Potential Movement promised that you could remake yourself completely, independent of failing institutions.

We’re seeing the same pattern now, but on steroids. Traditional religious attendance plummets while astrology apps proliferate. Political parties hemorrhage members while QAnon gains adherents. Universities lose credibility while YouTube gurus gain millions of followers. The metamodern condition that thinkers like Sloterdijk describe is one where we simultaneously know too much (we’re post-everything) and believe too readily (we’re desperate for meaning). We’re ironic about everything except our own desperate search for transformation.

Trauma and the Gnostic Temptation

Here’s where it gets really interesting for therapists. Voegelin understood that gnostic thinking often emerges from genuine suffering. When reality becomes unbearable, the promise of secret knowledge that can transform everything becomes irresistible. But there’s a crucial distinction here between healthy and unhealthy responses to powerlessness.

When external power is stripped away – through trauma, oppression, economic hardship, or institutional failure – turning inward can be profoundly healing. This is the basis of all genuine spiritual development and psychological growth. We discover our own agency, question received wisdom, develop personal practices, and find strength we didn’t know we had. Trauma therapy at its best helps people reclaim this kind of power – the power to feel, to choose, to heal, to grow.

But here’s where it gets dangerous: this inward turn becomes pathological when we start believing in external saviors who will magically restore our power. The moment we project our agency onto a messianic figure – whether that’s a political leader, a guru, a therapeutic modality, or even a conspiracy theory that explains everything – we’ve crossed from healthy inwardness to gnostic escape. We’ve traded real agency for the fantasy of magical deliverance.

Consider trauma survivors. The experience of trauma shatters assumptions about how the world works, creates desperate need for control and meaning, and makes the promise of total transformation through special knowledge incredibly seductive. This is why trauma survivors can be particularly vulnerable to conspiracy theories, rigid ideologies, perfectionist self-help systems, and black-and-white thinking about healing. The gnostic promise – “I have the answer that will make everything make sense” – is especially attractive to those whose worlds have been shattered.

The difference between healthy trauma recovery and gnostic escape is subtle but crucial. Healthy recovery says: “I can develop agency within my limitations, integrate this experience, and grow beyond who I was.” Gnostic escape says: “This special knowledge/person/practice will erase what happened and restore me to perfection.” One accepts the ongoing work of being human; the other promises magical transcendence of the human condition.

The Anxiety of Existence

Voegelin argued that at the root of gnostic thinking is something he called “the anxiety of existence” – the fundamental human discomfort with uncertainty, mortality, imperfection, and the fact that life includes suffering. Instead of learning to tolerate this anxiety, the gnostic personality seeks to escape it through ideological certainty, promises of transformation, demonization of enemies, and fantasies of final solutions.

But here’s what’s crucial for our time: this anxiety is massively amplified when the traditional containers for it – religious rituals, civic participation, community bonds, institutional authority – have eroded. David Tacey argues that we’re not really secular at all; we’re post-secular, meaning the sacred energies that once flowed through established channels now surge wildly through culture, seeking new forms. The result is what we might call “free-floating sanctity” – spiritual intensity without spiritual wisdom, religious fervor without religious tradition, mystical experience without mystical discipline.

This helps explain why our era produces such a volatile mix of genuine spiritual seeking and dangerous magical thinking. The same energies that once powered cathedral building now power conspiracy theories. The same devotion that once went to saints now goes to political strongmen. The same hunger for transformation that once drove monastic discipline now drives extreme wellness regimens. Without containers, the sacred becomes chaotic.

The metamodern sensibility that cultural critics identify – that oscillation between sincerity and irony, naivety and knowingness – reflects this condition perfectly. We know too much to simply believe, but we need too much to simply doubt. So we believe “as if” – maintaining ironic distance while desperately seeking genuine transformation. This is why someone can simultaneously mock astrology and check their horoscope, laugh at conspiracy theories and share them “just in case,” critique capitalism and hustle for wealth.

What Voegelin Means for Therapy

So what do we do with all this? How does understanding Voegelin help us in the therapy room?

1. Recognize Gnostic Patterns

When clients present with rigid ideological thinking, we can recognize it as a defense against existential anxiety rather than just “being political” or “being difficult.”

2. Address the Underlying Anxiety

Instead of arguing about the content of their beliefs, we can explore: What uncertainty are you trying to escape? What pain is this certainty protecting you from?

3. Tolerance for Ambiguity

We can help clients develop what Voegelin called “openness to the ground of being” – the ability to live with mystery, uncertainty, and imperfection without needing to escape into ideological certainty.

4. The Metaxy

Voegelin used the Greek term “metaxy” (the in-between) to describe the human condition – we’re neither beasts nor gods, neither purely material nor purely spiritual. We live in tension. Therapy can help people learn to inhabit this tension rather than escape it.

5. Healthy Transcendence

Not all spiritual seeking is gnostic. Voegelin distinguished between:

- Gnostic Escape: Trying to transform the world to escape the human condition

- Genuine Transcendence: Accepting reality while remaining open to mystery and meaning

Good therapy helps people find the latter.

The Politics of the Therapy Room

Here’s something uncomfortable: the therapy world isn’t immune to gnostic thinking. How many therapeutic modalities promise total transformation? How many therapists believe they have THE method that will heal all trauma? How many clients come seeking the perfect therapist who will have the magic key to their healing?

Voegelin challenges us to examine our own gnostic tendencies:

- Do we promise more than we can deliver?

- Do we demonize other approaches?

- Do we believe we can eliminate suffering rather than help people bear it?

- Do we subtly encourage clients to see us as possessors of secret knowledge?

Working with Modern Gnostics

So your client is deep into QAnon, or they’re convinced that Bitcoin will usher in a new world order, or they believe that their ex is a narcissist and once everyone realizes this, justice will prevail. What do you do? The key is recognizing that these beliefs often emerge from a real crisis of institutional authority combined with genuine powerlessness. Your client isn’t crazy – they’re responding to a crazy-making situation where traditional sources of meaning have failed them.

Don’t attack the content directly. Arguing about whether the conspiracy is true misses the point. The content is a symptom, not the disease. Instead, explore the function: What does this belief system do for them? What anxiety does it soothe? What chaos does it organize? Often you’ll find it provides exactly what failed institutions no longer offer: community, meaning, the feeling of being special or chosen, hope for dramatic change.

Validate the underlying needs. The need for meaning, order, and hope is legitimate. It’s the gnostic solution that’s the problem, not the human needs it addresses. Help them see that their turn inward – their recognition that they can’t rely on external authorities – is actually healthy. It’s the projection of their power onto a savior figure or magical system that’s keeping them stuck.

Introduce complexity gradually. Black-and-white thinking doesn’t yield to direct assault. Instead, gently introduce shades of gray. “I wonder if there might be other ways to look at this…” Help them see that accepting complexity doesn’t mean giving up agency – it means exercising agency in a more nuanced way. Model tolerance for uncertainty. Your own comfort with not knowing, with ambiguity, with the both/and rather than either/or, becomes a powerful therapeutic tool. You’re showing them that it’s possible to have power without having all the answers.

Most importantly, help them distinguish between healthy inward development and unhealthy outward projection. Yes, they’re right that they can’t trust many institutions. Yes, they’re right that they need to develop their own power. But that power comes from patient inner work, not from finding the perfect leader or system. The moment they put their hope in Trump or Bitcoin or a guru or even a therapeutic modality as savior, they’ve given away the very agency they’re trying to reclaim.

The Pneumopathology of Everyday Life

Voegelin’s concept of “pneumopathology” – spiritual disease – might sound dramatic, but we see mild forms of it everywhere. The wellness influencer who promises their diet will cure all disease, the self-help guru who claims their method will eliminate all negative emotions, the political activist who believes their candidate will save or destroy America, the therapy client who thinks finding the perfect diagnosis will solve everything, the spiritual seeker who believes enlightenment will end all suffering – these are all variations on the gnostic theme.

What’s particularly striking about our moment is how rapid the changes are. Previous gnostic movements took decades or centuries to develop. The Mithraic mysteries spread slowly through the Roman legions. Early Christianity took three hundred years to conquer the empire. Even the New Age movement of the 1970s built gradually over a decade. But now? QAnon went from obscure message board posts to millions of believers in less than three years. Cryptocurrency true believers created a quasi-religious movement almost overnight. Social media influencers build cult-like followings in months.

This acceleration reflects both the collapse of traditional authorities and the technological amplification of gnostic tendencies. When institutions fail, the hunger for meaning becomes acute. When that hunger meets social media algorithms that reward extreme content, engagement-driving conspiracy theories, and the formation of echo chambers, gnostic movements can achieve viral spread. Peter Sloterdijk calls this “spherological catastrophe” – the protective bubbles of meaning that once took generations to build and destroy now inflate and pop in real-time.

The result is a peculiarly modern form of suffering: gnostic burnout. People cycle through belief systems at increasing speed, each time hoping they’ve found “the answer,” each time eventually disappointed. They might go from New Age spirituality to political activism to cryptocurrency to wellness culture to therapy obsession, always seeking the key that will unlock perfect life. This rapid cycling between hope and disappointment, projection and disillusionment, creates its own form of trauma.

Climate Change and Gnostic Responses

Even our response to real crises can take gnostic forms. Climate change is real, but notice how responses can split into:

Gnostic Doomism: We’re all going to die, there’s no hope, only those who see the truth understand how bad it is

Gnostic Denialism: It’s all a hoax by the elites to control us, only we know the real truth

Gnostic Solutionism: If we just implement this one policy/technology/lifestyle change, we’ll save the world

Voegelin would encourage a non-gnostic response: Yes, it’s a serious problem. No, there’s no magic solution. We must act while accepting uncertainty and imperfection.

The Social Media Acceleration

Voegelin died before social media, but he would have immediately recognized how it amplifies gnostic tendencies:

- Echo Chambers: Communities of the “knowing” who reinforce each other’s certainties

- Algorithmic Radicalization: The most extreme voices get the most engagement

- Constant Crisis: Everything is always apocalyptic

- Influencer Gurus: New gnostic teachers with millions of followers

- Information Overload: Creating more anxiety that drives people toward simple answers

Our clients are swimming in this soup every day. No wonder gnostic thinking is on the rise.

Therapeutic Implications for Different Populations

Working with Trauma Survivors

Understanding gnostic patterns helps us recognize when trauma healing becomes its own ideology:

- The search for the perfect trauma therapy

- The belief that complete healing will erase all effects

- The tendency to divide the world into trauma-informed (good) and non-trauma-informed (bad)

- The fantasy of returning to a pre-trauma state

Healthy trauma work accepts that while healing is possible, some effects may remain. We’re aiming for post-traumatic growth, not time travel.

Working with Political Extremists

Whether left or right, political extremists often show classic gnostic patterns:

- Possession of the saving truth

- Division of the world into enlightened and ignorant

- Apocalyptic thinking

- Justification of extreme measures

Therapy involves helping them reconnect with human complexity, their own and others’.

Working with Spiritual Seekers

Not all spiritual seeking is gnostic, but warning signs include:

- Claims of special knowledge others don’t have

- Promises of total transformation

- Demonization of the material world

- Extreme practices aimed at escaping the human condition

Healthy spirituality accepts the metaxy – we’re spiritual beings having a human experience, not gods trapped in meat suits.

Working with Success-Obsessed Clients

The gnostic pattern appears in career and financial obsession:

- The next level of success will bring happiness

- Those who don’t succeed are doing something wrong

- There’s a secret formula the successful know

- Material success equals spiritual worth

Therapy involves reconnecting with intrinsic worth beyond achievement.

The Question of Diagnosis

Interestingly, even our diagnostic system can take on gnostic characteristics. How many clients come in convinced that:

- The right diagnosis will explain everything

- Once they know what’s “wrong” with them, they’ll be fixed

- Their diagnosis makes them special/different/misunderstood

- Only others with the same diagnosis can understand them

This isn’t to say diagnosis isn’t useful – it is. But when it becomes a totalizing identity or a promise of transformation, we’re in gnostic territory.

Voegelin’s Own Journey

It’s worth noting that Voegelin’s insights came from personal experience. He lived through:

- The collapse of the Austrian Empire

- The rise of Nazism

- Exile from his homeland

- The Cold War

He saw firsthand how intelligent, educated people could fall under the spell of ideologies that promised to create heaven on earth but delivered hell instead. His work was an attempt to understand: How does this happen? And how can we prevent it?

His answer: by recognizing the gnostic pattern and developing what he called “resistance to untruth.”

Practical Exercises for Developing Non-Gnostic Consciousness

Here are some exercises you can use with clients (or yourself) to develop resistance to gnostic thinking:

1. The Both/And Practice

When tempted to think in absolutes, practice holding opposites:

- My ex was both hurtful AND human

- The political situation is both concerning AND has been survived before

- I am both wounded AND whole

- Life is both meaningful AND absurd

2. The Uncertainty Journal

Keep a journal of things you don’t know and can’t know:

- Why did this happen to me?

- What will the future bring?

- What happens after death?

- Why does evil exist?

Notice how it feels to not know. Practice sitting with that feeling.

3. The Complexity Challenge

When tempted to simple explanations, ask:

- What else might be true?

- Who benefits from this certainty?

- What am I avoiding by being so sure?

- How might someone I respect see this differently?

4. The Ordinary Sacred

Gnostic thinking often despises the ordinary. Practice finding meaning in:

- Daily routines

- Simple pleasures

- Imperfect relationships

- Small kindnesses

5. The Historical Perspective

Read about past movements that promised transformation:

- Where are they now?

- What happened to the believers?

- What patterns do you notice?

- How might our current certainties look in 100 years?

The Therapeutic Relationship as Metaxy

Perhaps most importantly, the therapeutic relationship itself can model non-gnostic relating. In the therapy room:

- We don’t have all the answers

- We can’t promise total transformation

- We accept imperfection (our own and our clients’)

- We hold hope without guarantees

- We tolerate uncertainty together

- We find meaning without absolutes

This is what Voegelin meant by living in the metaxy – the in-between space where real human life happens.

Integration and Moving Forward

So where does this leave us? If we can’t escape into gnostic certainty, how do we live?

Voegelin’s answer was something like this: We live in the tension. We accept that we’re neither beasts nor angels. We seek truth while accepting we’ll never fully possess it. We work for justice while knowing perfection is impossible. We love while knowing loss is inevitable. We hope while accepting uncertainty.

This isn’t pessimism – it’s realism that makes genuine joy possible. When we stop expecting life to be other than it is, we can fully experience what it actually offers.

The Continuing Relevance

As I write this, the world seems particularly susceptible to gnostic thinking: political polarization, conspiracy theories, technological utopianism, wellness extremism, financial magical thinking, and therapeutic perfectionism. Voegelin’s framework helps us understand these not as separate phenomena but as variations on an ancient theme: the human desire to escape the human condition. But what’s new is the specific context – the failure of traditional institutions, the speed of change, and the technological amplification of both genuine seeking and dangerous delusion.

The philosophers and thinkers exploring these territories – Sloterdijk with his spherology, Tacey with his post-secular sacred, the metamodernists with their oscillating sensibilities – are all grappling with the same phenomenon Voegelin identified: what happens to human consciousness when the traditional containers for the sacred collapse? Their answer seems to be that we’re in a transitional moment, neither able to go back to traditional belief nor forward to pure secularism. Instead, we’re stuck in what Sloterdijk calls “the in-between” – a space of both opportunity and danger.

The opportunity lies in genuine spiritual development freed from institutional corruption. When people turn inward because external authorities have failed, they sometimes find authentic wisdom, real healing, and true agency. The trauma therapy movement at its best represents this – people learning to trust their own experience, heal their own wounds, and develop their own strength. The danger lies in mistaking magical thinking for spiritual development, projection for empowerment, and savior fantasies for genuine transformation. When the inward turn becomes a search for the perfect guru, system, or leader who will restore our power, we’ve fallen into what Voegelin would recognize as the oldest trap in human history.

A Personal Note

I’ll confess: I’ve had my own gnostic moments. The belief that if I just found the right therapy, read the right book, understood the right theory, everything would click into place. Maybe you have too. Maybe that’s what brought you to this article – the hope that understanding Voegelin would be the key that unlocks everything.

If so, I have bad news and good news. The bad news is that Voegelin isn’t the answer. There is no answer, no key, no final solution. The good news is that once we accept this, we can stop the exhausting search for the non-existent key and start the rewarding work of living as we actually are: limited, mortal, uncertain beings capable of love, meaning, and genuine (if imperfect) healing.

What makes our moment unique is that we’re doing this work without a net. Previous generations had institutions – however flawed – that provided some structure for the search. We’re improvising, making it up as we go, turning to Instagram therapists and YouTube philosophers because the universities and churches no longer speak to us. This is terrifying and liberating in equal measure.

The Sacred Anarchy of Now

What we’re living through might be called a period of “sacred anarchy” – the old orders have collapsed but the new ones haven’t yet emerged. In this space, genuine prophets and dangerous charlatans are almost impossible to distinguish. Someone might find real healing through a TikTok trauma coach or get sucked into a destructive cult through the same platform. The same online community might foster genuine mutual aid or devolve into extremist echo chambers.

This is why Voegelin’s distinction between healthy and pathological responses to powerlessness is so crucial right now. When your client tells you they’ve found meaning through cryptocurrency, or that they’re following a spiritual teacher on Instagram, or that they believe a political movement will transform society, the question isn’t whether these things are “true” or “false.” The question is: Are they using these beliefs to develop genuine agency or to escape into fantasy? Are they doing the hard work of integration or seeking magical deliverance?

The therapeutic task in our time is incredibly delicate. We need to honor the genuine spiritual emergency that drives people to seek transformation while helping them avoid the gnostic trap of projecting their power onto external saviors. We need to validate their correct perception that institutions have failed while helping them see that no perfect substitute exists. We need to support their inward turn while watching for signs that it’s becoming an escape rather than a journey.

Technology and the Gnostic Acceleration

One factor Voegelin couldn’t have anticipated is how technology would supercharge gnostic tendencies. Social media doesn’t just spread gnostic movements faster – it fundamentally changes their character. The algorithm rewards engagement, and nothing engages like the promise of secret knowledge or the threat of hidden enemies. The more extreme the claim, the more viral it goes.

But there’s something deeper happening. The internet itself functions as a kind of gnostic space – a realm of pure information where material constraints seem to disappear, where identity can be endlessly reconstructed, where communities form around shared gnosis rather than physical proximity. In this digital realm, the promise of transformation through knowledge seems almost plausible. After all, doesn’t the right information literally transform your feed, your connections, your entire online world?

This creates what we might call “digital gnosticism” – the belief that the right algorithm, platform, or online community will deliver us from the human condition. We see this in everything from life-hacking culture to the obsession with optimization, from digital nomadism to the metaverse. Each promises escape from material limitations through technological transcendence.

The Therapeutic Stance in Sacred Anarchy

So how do we, as therapists, position ourselves in this landscape? Voegelin suggests something like radical humility combined with radical presence. We can’t offer the certainty our clients seek, but we can offer something more valuable: companionship in uncertainty. We can’t be their saviors, but we can help them stop looking for saviors. We can’t provide the missing institution, but we can help them build internal structures that no institution could provide.

This means reimagining therapy itself. We’re not just treating individual pathology anymore – we’re helping people navigate civilizational transition. Our clients aren’t just working through personal trauma – they’re processing collective disorientation. The anxiety in the room isn’t just biographical – it’s historical, spiritual, existential.

Some practical implications: First, we need to educate ourselves about the spiritual and political movements our clients are drawn to, not to become experts but to understand the needs these movements address. Second, we need to develop our own tolerance for not knowing, because our clients will test it constantly. Third, we need to find ways to honor spiritual seeking while maintaining therapeutic boundaries. Fourth, we need to recognize when we ourselves are falling into gnostic thinking about therapy’s power to transform.

Beyond Gnosticism: The Wisdom of Limits

Voegelin’s great gift to psychotherapy isn’t a new technique or intervention. It’s a lens through which to see the patterns that trap us and our clients in cycles of false hope and inevitable disappointment. By recognizing gnostic thinking – in ourselves, our clients, our culture – we can offer something more valuable than false promises: the companionship of someone willing to stay in the tension with them.

But perhaps more importantly, Voegelin points toward what comes after we abandon gnostic fantasies. He called it “openness to the ground of being” – a stance that remains receptive to genuine mystery without trying to possess or control it. In our context, this might mean helping clients discover that real power comes not from finding the perfect system or savior but from accepting their own capacity to respond creatively to an imperfect world.

The irony is that when we stop seeking magical transformation, actual transformation becomes possible. When we stop looking for saviors, we might discover our own capacity to save what can be saved. When we accept the limits of knowledge, we open to wisdom. When we give up the fantasy of escape from the human condition, we can begin to inhabit it with grace.

This is not resignation – it’s a different kind of hope. Instead of hoping for escape, we hope for the strength to stay present. Instead of hoping for perfection, we hope for the wisdom to work with imperfection. Instead of hoping for saviors, we hope for the courage to take responsibility for what we can actually influence.

Conclusion: The Wisdom of Limits

In a world gone mad with certainty, the ability to say “I don’t know, but I’ll stay with you while we figure out how to live with not knowing” might be the most radical and healing thing we can offer. This is not therapeutic nihilism – it’s therapeutic realism that makes genuine growth possible.

As Voegelin might say, we can’t escape the human condition, but we can learn to inhabit it with grace, wisdom, and appropriate humor about our own pretensions to godhood. In an age of collapsed institutions and proliferating gnosticisms, this might be the most subversive stance of all: to insist on being merely, fully, courageously human.

The ultimate irony is that by accepting our limits – as therapists, as humans, as meaning-making creatures in a mysterious universe – we discover our actual power. Not the gnostic fantasy of total transformation, but the real capacity to heal, to grow, to create meaning in the midst of uncertainty. Not the promise of escape from the human condition, but the possibility of inhabiting it with something approaching wisdom.

And maybe, just maybe, in this time of sacred anarchy and institutional collapse, that’s exactly what we need: not new saviors or perfect systems, but people willing to do the difficult work of being human together, without guarantees, without magic formulas, without escape routes – just the ancient, difficult, necessary work of learning to live with grace in the tension between earth and heaven, knowledge and mystery, power and powerlessness.

That’s what Voegelin offers us: not another ideology to believe in, but a way of seeing through ideologies. Not another promise of transformation, but the wisdom to recognize such promises as the perennial human temptation they are. Not another system to master, but the humility to acknowledge that mastery itself might be the problem.

In our therapeutic work, in our own lives, in this strange historical moment, that might be the beginning of genuine wisdom.

Tags

Eric Voegelin, political philosophy, gnosticism, psychotherapy integration, trauma therapy, political extremism, January 6th Capitol, market fundamentalism, pneumopathology, existential anxiety, ideological possession, metaxy, therapeutic philosophy, political religion, modern consciousness

Bibliography

Primary Sources by Eric Voegelin

Voegelin, Eric. The New Science of Politics: An Introduction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1952.

Voegelin, Eric. Order and History, Volume I: Israel and Revelation. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1956.

Voegelin, Eric. Order and History, Volume II: The World of the Polis. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1957.

Voegelin, Eric. Order and History, Volume III: Plato and Aristotle. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1957.

Voegelin, Eric. Order and History, Volume IV: The Ecumenic Age. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1974.

Voegelin, Eric. Order and History, Volume V: In Search of Order. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1987.

Voegelin, Eric. Science, Politics, and Gnosticism: Two Essays. Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1968.

Voegelin, Eric. From Enlightenment to Revolution. Ed. John H. Hallowell. Durham: Duke University Press, 1975.

Voegelin, Eric. Anamnesis: On the Theory of History and Politics. Trans. Gerhart Niemeyer. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1978.

Voegelin, Eric. Autobiographical Reflections. Ed. Ellis Sandoz. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1989.

Voegelin, Eric. Published Essays, 1966-1985. Ed. Ellis Sandoz. Vol. 12 of The Collected Works of Eric Voegelin. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1990.

Voegelin, Eric. Modernity Without Restraint: The Political Religions; The New Science of Politics; and Science, Politics, and Gnosticism. Ed. Manfred Henningsen. Vol. 5 of The Collected Works of Eric Voegelin. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2000.

Secondary Sources on Voegelin

Cooper, Barry. Eric Voegelin and the Foundations of Modern Political Science. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999.

Federici, Michael P. Eric Voegelin: The Restoration of Order. Wilmington: ISI Books, 2002.

Hughes, Glenn. Mystery and Myth in the Philosophy of Eric Voegelin. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1993.

McAllister, Ted V. Revolt Against Modernity: Leo Strauss, Eric Voegelin, and the Search for a Postliberal Order. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1996.

Sandoz, Ellis. The Voegelinian Revolution: A Biographical Introduction. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1981.

Webb, Eugene. Eric Voegelin: Philosopher of History. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1981.

Works on Political Religion and Gnosticism

Burleigh, Michael. Sacred Causes: The Clash of Religion and Politics, from the Great War to the War on Terror. New York: HarperCollins, 2007.

Gray, John. Black Mass: Apocalyptic Religion and the Death of Utopia. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007.

Jonas, Hans. The Gnostic Religion: The Message of the Alien God and the Beginnings of Christianity. Boston: Beacon Press, 1958.

Lilla, Mark. The Stillborn God: Religion, Politics, and the Modern West. New York: Knopf, 2007.

Pellicani, Luciano. Revolutionary Apocalypse: Ideological Roots of Terrorism. Westport: Praeger, 2003.

Works on Trauma and Ideology

Alexander, Jeffrey C. Trauma: A Social Theory. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2012.

Lifton, Robert Jay. Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism: A Study of “Brainwashing” in China. New York: Norton, 1961.

Herman, Judith. Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence from Domestic Abuse to Political Terror. New York: Basic Books, 1992.

Van der Kolk, Bessel. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York: Viking, 2014.

Works on Contemporary Political Psychology

Haidt, Jonathan. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. New York: Pantheon, 2012.

Hoffer, Eric. The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements. New York: Harper & Row, 1951.

Keltner, Dacher. The Power Paradox: How We Gain and Lose Influence. New York: Penguin Press, 2016.

Snyder, Timothy. The Road to Unfreedom: Russia, Europe, America. New York: Tim Duggan Books, 2018.

Works on Psychotherapy and Philosophy

Frankl, Viktor E. Man’s Search for Meaning. Boston: Beacon Press, 1959.

May, Rollo. The Discovery of Being: Writings in Existential Psychology. New York: Norton, 1983.

Stolorow, Robert D. Trauma and Human Existence: Autobiographical, Psychoanalytic, and Philosophical Reflections. New York: Routledge, 2007.

Yalom, Irvin D. Existential Psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books, 1980.

Works on Market Fundamentalism and Economic Ideology

Block, Fred, and Margaret R. Somers. The Power of Market Fundamentalism: Karl Polanyi’s Critique. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014.

Frank, Thomas. One Market Under God: Extreme Capitalism, Market Populism, and the End of Economic Democracy. New York: Doubleday, 2000.

Harvey, David. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Mirowski, Philip. Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown. London: Verso, 2013.

Works on Conspiracy Theories and Contemporary Extremism

Barkun, Michael. A Culture of Conspiracy: Apocalyptic Visions in Contemporary America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

Neiwert, David. Red Pill, Blue Pill: How to Counteract the Conspiracy Theories That Are Killing Us. New York: Prometheus Books, 2020.

Rosenblum, Nancy L., and Russell Muirhead. A Lot of People Are Saying: The New Conspiracism and the Assault on Democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019.

Timeline of Eric Voegelin’s Life and Work

1901 – Born on January 3 in Cologne, Germany, as Erich Hermann Wilhelm Vögelin

1910 – Family moves to Vienna, Austria, where Voegelin would spend his formative years

1919 – Begins studying law at the University of Vienna

1922 – Receives doctorate in political science from University of Vienna under Hans Kelsen and Othmar Spann

1924 – Publishes his first book, Über die Form des amerikanischen Geistes (On the Form of the American Mind)

1924-1926 – Studies in United States on Laura Spelman Rockefeller Fellowship, attending Columbia University, Harvard, and University of Wisconsin

1927 – Returns to Vienna; begins teaching at University of Vienna

1928 – Habilitates at University of Vienna with thesis on sociology of knowledge

1932 – Marries Lissy Onken

1933 – Publishes Rasse und Staat (Race and State), critically examining Nazi racial theories

1936 – Publishes Der autoritäre Staat (The Authoritarian State), analyzing Austrian politics

1938 – Publishes Die politischen Religionen (The Political Religions), introducing his concept of political religions

- Flees Austria with his wife following the Anschluss, as his writings had made him a target of the Nazis

1939 – Arrives in United States; takes temporary positions at Harvard and Bennington College

1942 – Joins Louisiana State University as associate professor of government

1946 – Becomes full professor at LSU

1948 – Delivers Walgreen Lectures at University of Chicago (later published as The New Science of Politics)

1951 – Becomes Boyd Professor of Government at LSU

1952 – Publishes The New Science of Politics, establishing his reputation as major political philosopher

1956 – Publishes first volume of Order and History: Israel and Revelation

1957 – Publishes volumes 2 and 3 of Order and History: The World of the Polis and Plato and Aristotle

1958 – Accepts appointment at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Germany, establishing new Institute for Political Science

1964 – Delivers lectures later published as Science, Politics, and Gnosticism

1966 – Delivers Candler Lectures at Emory University on “The Drama of Humanity”

1968 – Publishes expanded version of Science, Politics, and Gnosticism

1969 – Returns to United States, joining Stanford University’s Hoover Institution

1974 – Publishes volume 4 of Order and History: The Ecumenic Age, showing major shift in his philosophical approach

1975 – From Enlightenment to Revolution published posthumously from his lectures

1978 – German edition of Anamnesis published (English translation 1978)

1985 – Dies on January 19 at Stanford University at age 84

1987 – Volume 5 of Order and History: In Search of Order published posthumously

1989 – Autobiographical Reflections published

1990s-2000s – Collected Works of Eric Voegelin published in 34 volumes by University of Missouri Press

Legacy Period (1985-present)

- Establishment of Eric Voegelin Society (1987)

- Creation of Voegelin centres at universities worldwide

- Growing influence on political theory, philosophy of consciousness, and religious studies

- Increasing application of his ideas to contemporary political and social analysis

0 Comments