The Prescient Wisdom of Dr. Shoma Morita: Metacognition, Eastern Philosophy, and the Limits of Psychopharmacology

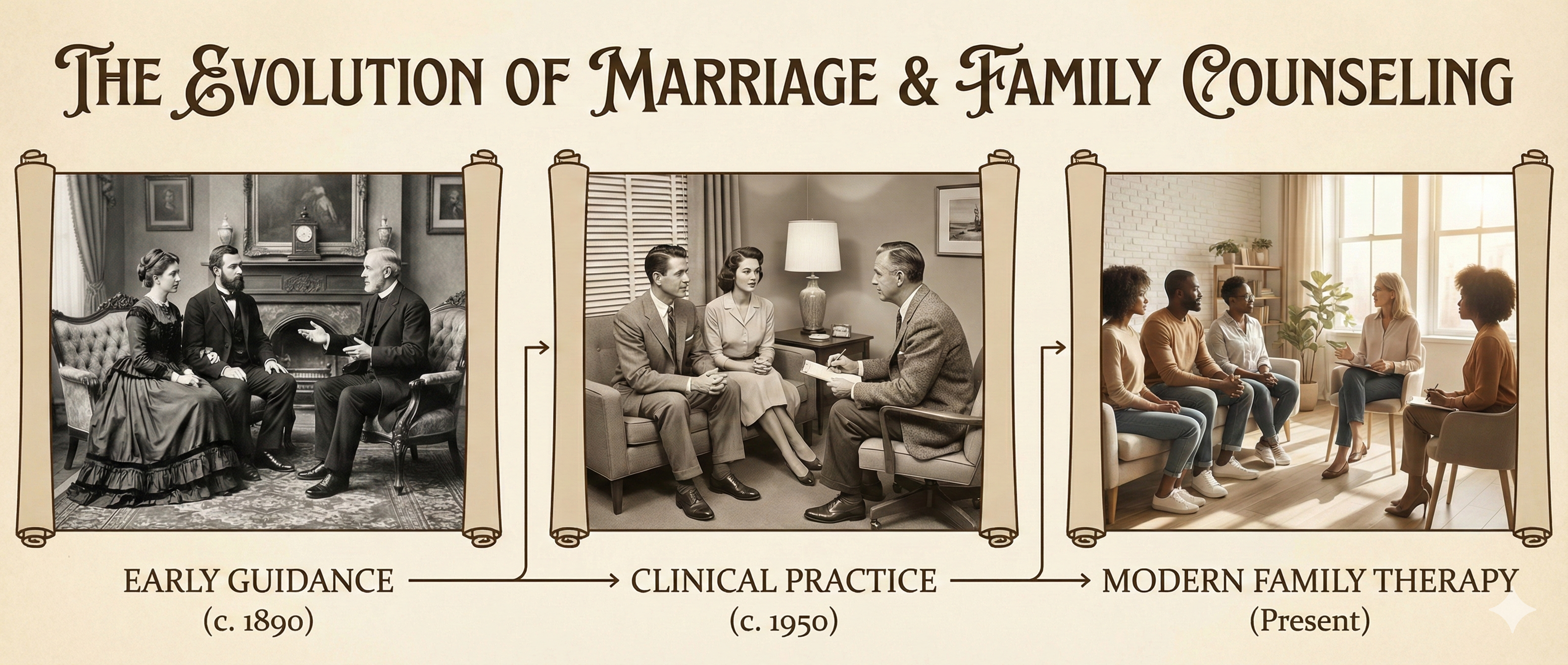

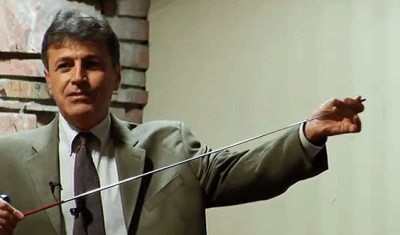

In the early 20th century, while Western psychiatry was still grappling with Freudian theories and the nascent field of psychopharmacology, a Japanese psychiatrist named Shoma Morita was developing a radically different approach to mental health. His insights, rooted in Eastern philosophy yet informed by medical training, anticipated many of the developments that Western psychology would only embrace decades later. More importantly, Morita’s work offers a crucial perspective on the limitations of our current medication-centered approach to mental health and the fundamental role of metacognition in healing.

The Revolutionary Simplicity of Morita’s Insight

Dr. Shoma Morita (1874-1938) developed his therapeutic approach while treating patients with what was then called “shinkeishitsu” – a condition characterized by anxiety, obsessive thoughts, and hypochondriacal concerns. Unlike his Western contemporaries who sought to analyze and eliminate symptoms, Morita proposed something revolutionary: that the attempt to control or suppress difficult emotions was itself the primary source of suffering.

At the heart of Morita’s approach was a profound understanding of metacognition – the awareness of one’s own thought processes. He recognized that healing came not from changing thoughts or feelings directly, but from changing one’s relationship to them. This was not merely philosophical speculation; it was a practical therapeutic approach that yielded remarkable results. Morita understood that metacognition – the ability to observe our mental processes without being consumed by them – was the mechanism through which genuine psychological transformation occurred.

The Limits of Psychopharmacology: What Can and Cannot Be Drugged

Morita’s insights become particularly relevant when we examine the modern landscape of psychopharmacology. While medications have undoubtedly provided relief for millions suffering from mental health conditions, they operate within specific parameters that Morita intuitively understood. Psychotropic medications can effectively target certain neurochemical imbalances – they can lift the fog of depression, quiet the racing thoughts of anxiety, or stabilize the extremes of bipolar disorder. These interventions work at the level of neurotransmitters, adjusting serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine, and other chemical messengers in the brain.

However, Morita recognized what modern psychiatry is only beginning to fully acknowledge: there are fundamental aspects of human emotional experience that cannot be medicated away. Grief over loss, existential anxiety about meaning and mortality, the pain of difficult relationships, the struggle with identity and purpose – these are not pathologies to be cured but inherent aspects of the human condition that must be experienced and integrated.

The distinction is crucial. While medication can address the biological substrates that may make someone more vulnerable to depression or anxiety, it cannot teach someone how to relate differently to their thoughts. It cannot provide the metacognitive skills necessary to observe one’s mental patterns without being overwhelmed by them. It cannot instill the acceptance and purposeful action that Morita saw as essential to psychological well being.

Anticipating the Integration of Eastern Wisdom

What makes Morita’s work particularly prescient is how it anticipated the eventual Western embrace of Eastern contemplative practices. Decades before Jon Kabat-Zinn would introduce Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, before Marsha Linehan would develop Dialectical Behavior Therapy with its emphasis on radical acceptance, before the third wave of cognitive-behavioral therapies would incorporate mindfulness and acceptance-based strategies, Morita was already integrating these principles into his therapeutic approach.

Morita’s therapy incorporated elements that would later become cornerstones of Western psychotherapy:

Somatic awareness:

Morita encouraged patients to notice bodily sensations without trying to change them, recognizing that the body holds wisdom and that fighting physical manifestations of emotion only amplifies distress.

Experiential acceptance:

Rather than analyzing why one felt anxious or depressed, Morita therapy emphasized accepting these states as natural fluctuations of human experience, like weather passing through.

Mindful observation:

Patients were taught to observe their thoughts and feelings with detached interest, developing what we now recognize as metacognitive awareness.

Values-based action:

Despite internal discomfort, patients were encouraged to engage in meaningful activities, prefiguring what Acceptance and Commitment Therapy would later call “committed action.”

The integration of these Eastern-influenced practices into Western psychotherapy represents a vindication of Morita’s early insights. He understood that the Western tendency to pathologize and eliminate uncomfortable emotions was itself problematic, and that true healing required a fundamental shift in how we relate to our inner experience.

The Metacognitive Revolution That Never Quite Happened

Morita believed that developing metacognitive awareness – the ability to observe one’s thoughts and feelings without being identified with them – should be the primary goal of any therapeutic intervention. This capacity for self-observation creates the space necessary for genuine choice and change. When we can see our patterns of thinking and feeling as mental events rather than absolute truths, we gain the freedom to respond differently.

This understanding should have revolutionized both psychotherapy and psychopharmacology. Ideally, medication would be used not as an end in itself but as a tool to create the stability necessary for developing metacognitive skills. Therapy would focus not on eliminating symptoms but on cultivating the awareness and acceptance that allow for a different relationship with difficult experiences.

The Formulaic Trap of Modern Therapy

Instead, we have witnessed something quite different. The very success of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has, paradoxically, led to a mechanization of the therapeutic process. In the rush to create evidence-based, manualized treatments, we have sometimes lost sight of the deeply personal, experiential nature of psychological transformation.

Modern CBT, while effective for many conditions, can sometimes reduce therapy to a series of techniques and worksheets. Thoughts are challenged, behaviors are modified, and symptoms are tracked – all valuable interventions, but potentially missing the deeper metacognitive shift that Morita recognized as essential. The emphasis on changing thought content rather than developing a different relationship with thoughts can inadvertently reinforce the very struggle that maintains suffering.

This formulaic approach extends to psychopharmacology as well. The medical model, with its emphasis on symptom reduction and diagnostic categories, can obscure the reality that emotional suffering often carries meaning and that the goal is not always to eliminate discomfort but to develop the capacity to hold it differently. We prescribe medications to target specific symptoms without always considering whether those symptoms might be pointing toward necessary life changes or unprocessed experiences that need attention.

Reclaiming the Metacognitive Heart of Healing

Morita’s legacy challenges us to reconsider our approach to mental health treatment. Rather than seeing therapy and medication as tools for symptom elimination, we might view them as means for developing metacognitive capacity. This shift has profound implications:

For prescribers:

Medication becomes not just about achieving remission but about creating the conditions where patients can develop awareness and acceptance. The question shifts from “What symptoms need to be eliminated?” to “What support does this person need to develop a healing relationship with their experience?”

For therapists:

The focus moves beyond technique to the cultivation of presence and awareness. While evidence-based interventions remain important, they serve the larger goal of helping clients develop the capacity to observe their experience with compassion and clarity.

For patients:

The goal becomes not the absence of difficult emotions but the development of a wise and accepting relationship with the full spectrum of human experience. Success is measured not just by symptom reduction but by increased psychological flexibility and the ability to live meaningfully despite discomfort.

The Path Forward: Integration and Wisdom

As we move forward in our understanding and treatment of mental health, Morita’s insights offer a crucial corrective to our current approach. His work reminds us that:

- Metacognition is the mechanism of healing: Real transformation occurs not through the elimination of difficult thoughts and feelings but through changing our relationship to them.

- Some experiences cannot and should not be medicated: The full range of human emotion, including grief, existential anxiety, and spiritual longing, requires experiential processing rather than pharmaceutical intervention.

- Eastern wisdom has much to offer: The integration of mindfulness, acceptance, and somatic awareness into Western psychotherapy represents a return to insights Morita articulated a century ago.

- Therapy must remain an art: While evidence-based practices are valuable, the therapeutic process cannot be reduced to a formula. It requires presence, intuition, and a deep respect for the unique journey of each individual.

Honoring the Fullness of Human Experience

Dr. Shoma Morita’s contributions to psychiatry extend far beyond the specific therapeutic approach that bears his name. His recognition that metacognition heals, that acceptance paradoxically enables change, and that some aspects of human experience must be lived through rather than eliminated, offers profound wisdom for our current moment.

As we continue to advance in our understanding of the brain and develop new pharmacological interventions, we must not lose sight of these fundamental truths. The goal of mental health treatment should not be the creation of a symptom-free existence but the cultivation of the awareness, acceptance, and resilience that allow us to meet life’s inevitable challenges with grace.

Morita understood that suffering is not always pathology and that the attempt to escape difficult emotions often creates more suffering than the emotions themselves. In our rush to diagnose and treat, to categorize and eliminate, we risk losing touch with this wisdom. By returning to Morita’s insights and integrating them with our modern understanding, we can create an approach to mental health that honors both the biological realities of psychiatric conditions and the irreducibly human dimensions of emotional experience.

The future of mental health treatment lies not in choosing between medication and therapy, between Western and Eastern approaches, between symptom reduction and acceptance. It lies in integration – in recognizing that true healing requires both the relief that medication can provide and the transformation that comes through developing a different relationship with our inner experience. Morita saw this a century ago. It is time we fully embraced his vision.

0 Comments