The Birth of Computational Psychiatry: Joseph Weizenbaum and ELIZA

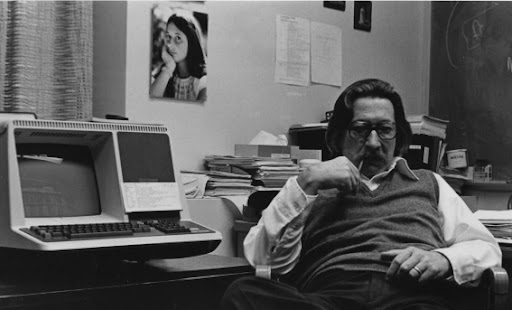

In the winter of 1966, MIT professor Joseph Weizenbaum sat in his office at the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, watching with growing unease as his secretary engaged in what appeared to be an intimate conversation with his computer program. She had asked him to leave the room so she could have privacy with ELIZA, his simple pattern-matching program that mimicked a Rogerian psychotherapist. This moment would haunt Weizenbaum for the rest of his life, crystallizing his fears about humanity’s willingness to attribute depth and understanding to machines that possessed neither.

In the winter of 1966, MIT professor Joseph Weizenbaum sat in his office at the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, watching with growing unease as his secretary engaged in what appeared to be an intimate conversation with his computer program. She had asked him to leave the room so she could have privacy with ELIZA, his simple pattern-matching program that mimicked a Rogerian psychotherapist. This moment would haunt Weizenbaum for the rest of his life, crystallizing his fears about humanity’s willingness to attribute depth and understanding to machines that possessed neither.

Weizenbaum, born in Berlin in 1923, had fled Nazi Germany with his family as a child. This early experience of dehumanization would profoundly shape his later skepticism about reducing human complexity to computational processes. After studying mathematics at Wayne State University and working on early computing systems at General Electric, he joined MIT in 1963, where he would create one of the most influential and misunderstood programs in the history of artificial intelligence.

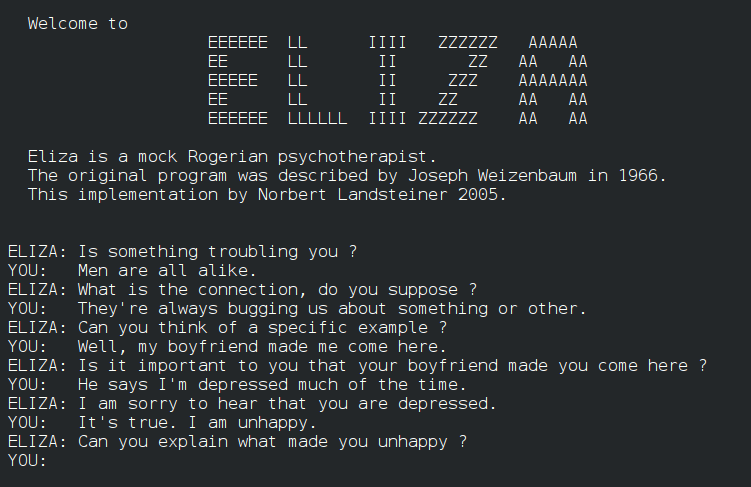

ELIZA was deceptively simple. It used pattern matching and substitution methodology to parrot back user statements as questions. If someone typed “I am sad,” ELIZA might respond, “Why do you say you are sad?” The program knew nothing about sadness, humanity, or the person typing. It was, as Weizenbaum insisted, a parlor trick—a demonstration of how easily humans could be fooled into believing a machine understood them.

The Seductive Dream of Algorithmic Therapy

What disturbed Weizenbaum most was not his program’s limitations but the enthusiasm with which it was embraced. Psychiatrists wrote to him suggesting ELIZA could be developed into an automated psychotherapy system. Kenneth Colby at Stanford created PARRY, a program simulating paranoid schizophrenia, envisioning a future where mental health treatment could be standardized, scalable, and scientifically precise.

This dream of algorithmic therapy emerged from a particular historical moment. The 1960s and 1970s saw the rise of behaviorism and cognitive theories that conceptualized the mind as an information-processing system. If thoughts were simply data and emotions were outputs of cognitive processes, then perhaps therapy could be reduced to debugging faulty programming. This mechanistic view promised to transform the messy, subjective world of psychotherapy into a clean, evidence-based science.

The appeal was obvious. Traditional psychotherapy was expensive, time-consuming, and dependent on the variable skills of individual therapists. An algorithmic approach promised democratized access to mental health care, consistent treatment protocols, and measurable outcomes. It was the ultimate expression of the modernist faith in rational systems and technological progress.

The Cognitive-Behavioral Paradigm and Its Discontents

This algorithmic dream found its fullest expression in the rise of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and the push toward manualized, evidence-based treatments. CBT, with its emphasis on identifying and correcting “cognitive distortions,” seemed perfectly suited to computerization. If depression was caused by negative thought patterns, couldn’t a program be designed to identify and challenge these patterns as effectively as a human therapist?

This algorithmic dream found its fullest expression in the rise of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and the push toward manualized, evidence-based treatments. CBT, with its emphasis on identifying and correcting “cognitive distortions,” seemed perfectly suited to computerization. If depression was caused by negative thought patterns, couldn’t a program be designed to identify and challenge these patterns as effectively as a human therapist?

The filmmaker Adam Curtis, in his documentary series “The Century of the Self,” traced how this mechanistic view of human psychology emerged from a broader cultural shift. Post-war consumer capitalism needed predictable, manageable subjects—people whose desires and behaviors could be mapped, predicted, and influenced. The cognitive-behavioral paradigm, with its assumption that humans operated like programmable computers, fit perfectly into this worldview.

But as Curtis warned, this reductionist view carried profound risks. By treating humans as machines to be reprogrammed, we risk losing sight of the irreducible complexity of human experience. The push to standardize therapy through randomized controlled trials and treatment manuals, while valuable for establishing efficacy, can obscure the deeply personal, contextual nature of psychological suffering and healing.

The Limits of Quantification

The attempt to reduce psychotherapy to evidence-based protocols runs into a fundamental problem: the most important aspects of therapeutic healing resist quantification. How do you measure the quality of presence a therapist brings to a session? How do you standardize the moment of genuine human connection that can shift a client’s entire perspective? How do you protocol-ize intuition, wisdom, or compassion?

Talented therapists have long recognized that their work involves an irreducibly subjective element. The therapeutic relationship itself—what researchers call the “therapeutic alliance”—consistently emerges as one of the strongest predictors of positive outcomes, yet it cannot be manualized or programmed. It emerges from the unique interplay between two human beings, shaped by their histories, personalities, and the ineffable chemistry between them.

This is not to dismiss the value of research or evidence-based practices. Understanding what techniques tend to be helpful for specific conditions is crucial. But the attempt to eliminate subjectivity and intuition from therapy in the name of scientific rigor risks throwing out precisely what makes therapy transformative.

The False Promise of AI Therapy

Today, as artificial intelligence grows more sophisticated, the dream of automated therapy has returned with renewed vigor. AI chatbots promise 24/7 availability, perfect consistency, and freedom from human judgment or bias. Machine learning algorithms claim to detect depression from speech patterns or predict suicide risk from social media posts.

Yet these technologies, for all their sophistication, remain fundamentally limited in the same way ELIZA was limited. They can process patterns and generate responses, but they cannot truly understand human experience. They have no lived experience of loss, joy, fear, or love to draw upon. They cannot offer the kind of embodied presence that allows a client to feel truly seen and held in their suffering.

More dangerously, the proliferation of AI therapy reinforces the mechanistic view of human psychology that Weizenbaum warned against. If we accept that our mental health can be adequately addressed by algorithms, we implicitly accept that we are nothing more than biological computers in need of debugging. This view not only diminishes human dignity but may actually impede healing by reinforcing the sense of disconnection and mechanization that contributes to modern psychological distress.

The Irreplaceable Human Elements

What cannot be captured in algorithms or research studies? The moment when a therapist’s eyes fill with tears as they witness their client’s pain. The intuitive sense that leads a therapist to remain silent just a moment longer, creating space for a breakthrough. The way a therapist’s own healing journey informs their ability to hold space for others. The subtle somatic awareness that alerts a therapist to unspoken trauma. The creative leap that suggests an unexpected intervention.

These elements emerge from the therapist’s full humanity—their embodied experience, their emotional attunement, their spiritual depth, their creative imagination. They cannot be standardized because they arise from the unique meeting of two irreducibly complex human beings.

Moreover, the healing process itself often involves reclaiming precisely those aspects of humanity that mechanistic approaches deny. Many clients come to therapy feeling like defective machines—believing they should be more productive, more positive, more “normal.” Healing involves reconnecting with their full humanity, including the messy, irrational, and mysterious aspects of their experience.

A Collaborative Future

None of this means we should reject technology or research in psychotherapy. Digital tools can increase access to care, provide valuable between-session support, and help track patterns that might otherwise go unnoticed. Research helps us understand what tends to work and avoid approaches that may cause harm.

But we must resist the temptation to reduce therapy to what can be measured and programmed. The future of psychotherapy lies not in replacing human connection with algorithms but in using technology to support and enhance the irreplacibly human aspects of healing.

This requires a fundamental shift in how we conceptualize mental health treatment. Rather than viewing therapist and client as programmer and program, we must embrace a truly collaborative model. Healing happens in the intersubjective space between two people, where both are changed by the encounter. It requires therapists who are willing to bring their full humanity to their work—their intuition, creativity, and vulnerability alongside their training and expertise.

The Enduring Warning

Joseph Weizenbaum spent his later years warning against the computer metaphor for human beings. In his 1976 book “Computer Power and Human Reason,” he argued that even if machines could someday replicate human behavior perfectly, there would remain a crucial distinction between simulation and authentic understanding. He worried about a world where efficiency and standardization would eclipse wisdom and compassion.

His warning feels more urgent than ever. As we rush to embrace AI solutions for human problems, we risk forgetting what makes us human in the first place. The promise of algorithmic therapy—consistent, scalable, evidence-based—remains seductive. But we must remember that psychological healing is not a technical problem to be solved but a deeply human process of growth, connection, and meaning-making.

The therapists who recognize this—who understand that their work will always involve irreducibly subjective and intuitive elements—need not fear being replaced by computers. Their willingness to show up as full human beings, to trust their intuition alongside their training, to collaborate rather than fix, makes them irreplaceable. In a world increasingly dominated by algorithms and automation, their commitment to human connection becomes not obsolete but essential.

As we shape the future of mental health care, we must hold onto Weizenbaum’s insight: we are not machines, and our healing cannot be mechanized. The subjective, the intuitive, the mysteriously human—these are not obstacles to effective therapy but its very heart. Any approach that tries to eliminate them in the name of progress risks losing precisely what we most need to preserve.

0 Comments